I’ve spent 25 years in security, and watching the news cycle of breaches never gets less frustrating. Another company compromised. Another million records stolen. Another ransomware payment. What makes it worse is that most of these incidents didn’t have to happen.

While working at Google and Stripe, I helped develop security invariants, which are technical controls that categorically eliminate entire attack surfaces. I wanted to understand which invariants were most effective, so I set out to analyse data breaches systematically.

Analysing 70 data breaches

To conduct this analysis at scale, I built a specialized AI-based framework I call PlanAI. Using the framework, I would collate public source data from the Internet and write a technical root cause analysis for each breach. I analysed about 70 data breaches, including most of the high-profile incidents: SolarWinds, the National Public Data breach from April 2024, and the Office of Personnel Management breach from 2015, among many others.

After completing the root cause analyses, I identified the security invariants I wanted to evaluate. Then I used reasoning models to determine which invariants could have prevented each breach.

The results were striking: over 65% of data breaches could have been prevented with just three security invariants.

Hardware second factors means password authentication requires a physical hardware token that must be touched to complete authentication. There’s no second factor that can be phished or stolen through social engineering — you need the physical device. The National Public Data breach is a perfect example. It could have been prevented with hardware second factors, as the leaked plaintext passwords alone would not have been sufficient for authentication.

Egress control means services in your infrastructure can only communicate with pre-approved destinations on the Internet. Many exploits require downloading a second-stage payload. If egress control prevents the connection to the server hosting that payload, the exploit chain breaks. Implementation isn’t particularly hard. You configure egress control proxies as the only path to the internet and enforce policy there. Third-party services offer similar capabilities, but they’re often buried in complex products, and most companies don’t realize they need this protection.

Positive execution control means only allowing known, trusted software to run. Nothing you don’t know about executes in your environment.

Three things. That’s it. 65% of breaches prevented.

Hitting the wall

I wanted to go deeper. There are other invariants that could prevent even more breaches. My favourite addresses insider risk: Employees or systems can only access customer data if there’s a validated business justification. A customer support agent can only pull up your record if they’re working on an active support case for you. Another is automatic deployment, where all services and applications are automatically deployed from checked-in source code, and your production environment mirrors your source code within two weeks.

But analysing the effectiveness of these additional invariants requires detailed knowledge of internal infrastructure — information that’s rarely disclosed in public breach reports. I had initially hoped that public sources would provide much more detail about the internal infrastructure of compromised companies. That didn’t turn out to be the case. Only very few data breach reports go into that level of detail.

I even explored whether insurance companies might have more detailed root cause analyses. That didn’t lead to easily accessible results either.

I hit a wall. Not because the analysis was wrong, but because I couldn’t go further with the data available.

The real problem: Incentives

As I stepped back, I realized the deeper problem wasn’t about identifying more invariants anyway. The real issue is that companies don’t implement even the well-known ones. And the reason why reveals a fundamental misalignment in how we approach security.

Imagine you’re the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) for a company. You just joined, and you do what CISOs do. You conduct a risk assessment, spend a few weeks on it, and present it to the executive team. It’s ranked, with the top risks at the top and lower risks below. You say, ‘With the resources you’ve given me, I can tackle the top two risks.’ The executive team agrees. You tackle those risks and make progress. Everyone’s happy.

Then a security compromise happens. A data breach. And it’s almost always one of the risks that wasn’t addressed — one further down the list that you didn’t have resources for. The conversation becomes: ‘Well, we decided to accept these risks. We couldn’t work on them because we only had resources for the top risks.’ The CISO usually gets fired because they failed. There was a data breach on their watch. Then the company hires a new one. The whole thing repeats.

This has been common knowledge in security for a long time. Most companies are rational actors making the best decisions they believe will help their business. In the current environment, data breaches are very common, and everybody has them. There’s very little incentive to prevent them.

How do you measure how good your security is? We haven’t really figured that out. The measurables you can bring are: This is how many vulnerabilities we found, this is how many we fixed, here are the remediated risks, and here are the accepted risks. But none of that lets you measure the return on investment (ROI) of security work because breaches usually happen in areas you didn’t secure.

Think about it this way: If you have a house with 10 doors and lock nine of them, you might say you’re 90% secure. But this is a Byzantine problem space. Adversaries are intelligent. Instead of trying the locked doors, they just go through the one you left unlocked.

When CEOs ask their CISOs, ‘What will we get for this investment?’, the answer is honest but unsatisfying: ‘No guarantees. Even with significant investment, we can’t promise zero incidents.’ So most CEOs make the rational choice and do the bare minimum, focus on growth and customer acquisition, and deal with security incidents when they happen.

The other problem is that societal costs are all indirect. When our data gets stolen — and most of our data has been stolen over and over again — it’s not the company that lost the data who bears the direct cost. The costs fall on individuals when this data is used for social engineering and identity theft. But that’s not directly measurable, and it’s certainly not directly attributable to any specific breach. So what do companies do? They offer credit monitoring and identity monitoring services that cost them maybe one or two dollars per affected person per year. Very little money compared to the actual harm. The company moves on. The individuals deal with the consequences for years.

Recently, there have been more stringent regulations requiring companies to at least disclose data breaches. In Europe, the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office initially proposed massive General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) fines against British Airways (GBP 183.39M) and Marriott International (GBP 99.2M) for data breaches affecting hundreds of millions of customers. However, the final fines issued in October 2020 were dramatically reduced to GBP 20M for British Airways and GBP 18.4M for Marriott; reductions of over 80% each, taking into account COVID-19 impacts, cooperation with investigators, and various mitigating factors.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted new rules in July 2023 requiring public companies to disclose material cybersecurity incidents within four business days. As of early 2025, companies are still struggling to determine what counts as ‘material’, with many initially over-reporting incidents before the SEC clarified its guidance.

But here’s the problem: These regulations focus on disclosure, not prevention. The regulations are succeeding at creating transparency, but transparency alone doesn’t change the underlying incentive structure. Companies are investing in compliance, that is, hiring lawyers, building disclosure processes, and conducting materiality assessments. They’re not necessarily investing more in prevention.

Why? Because the cost of non-compliance is still less than the cost of implementing comprehensive security invariants across their entire infrastructure. And even if they do get fined, the reductions in the British Airways and Marriott cases suggest that well-documented mitigation efforts can dramatically reduce penalties. Until the cost of breaches — whether through fines, insurance requirements, or loss of customer trust — exceeds the cost of prevention, the rational business decision remains: Do the minimum, accept the risk, deal with incidents when they happen.

There’s another dimension too. While these security invariants are well understood in highly functioning security organizations, they’re not widely known in general. And the ‘solutions’ being sold by the industry often aren’t real solutions at all. Talk to a CISO, and they’ll tell you about managing 20 to 30 third-party services that supposedly each solve one small problem but never come together into a coherent defence.

Each third-party service requires integration into existing workflows — integrations that are rarely perfect and often generate floods of difficult-to-triage alerts. Worse, each third-party service introduces its own security risk when it gets compromised. And since these services usually don’t know about each other, you end up with sprawl — lots of different vendors that don’t work well together.

There’s been a move towards consolidation, but in practice, many security organizations still manage way too many third-party services because they haven’t been able to create comprehensive solutions on their own. That’s really where security invariants can help, assuming you have an engineering team and the willingness, prioritization, and resources to implement them.

Implementing these invariants requires real software engineering, not just integrating third-party services. You need to build solutions. And retrofitting them into existing infrastructure is expensive and difficult.

Take egress control as an example. Deploying egress controls is straightforward if the system to manage egress policies is available from the beginning. Each engineering team, as they deploy a new service or make changes, edits the allow policy for that service — determining where it’s allowed to egress on the Internet and which external services it can talk to via DNS names. When you start with this foundation, deploying new services is easy because they’re built with these requirements in mind.

But if you already have many deployed services in your production environment, each service becomes a discovery problem. You’re trying to figure out what external Internet dependencies the service actually has. This is time-intensive. For many engineering teams, if it’s something they haven’t done before, they may not know how to approach it. There’s the risk that it may break production functionality. Some dependencies don’t show up often, maybe only once a month, depending on business processes. The complexities of retrofitting are very large. It seems risky, and teams are reluctant to do it.

A different approach: CISO Challenge

So, we’re left with a perfect storm: A broken incentive model that punishes CISOs for inevitable events, risk assessments that create a false sense of security, and the immense technical and political pain of retrofitting foundational controls. How do you convince a leadership team to invest in a difficult, expensive project when the ROI is the unsatisfying promise of ‘maybe something bad won’t happen’?

Data analysis and white papers can only go so far. You can’t just tell an executive about the compounding interest of technical debt or the flawed logic of the 10-door problem; they have to feel it.

This is where the idea for CISO Challenge was born. If we can’t change the industry with data alone, perhaps we can change minds through experience. I wanted to create a simulation where leaders and security professionals could experience these tradeoffs firsthand — to see a company flourish or fail based on their decisions. The goal is to make the long-term consequences of short-term thinking visceral, and to show how building on a solid foundation from the start is not just a security strategy, but a winning business strategy.

The game concept

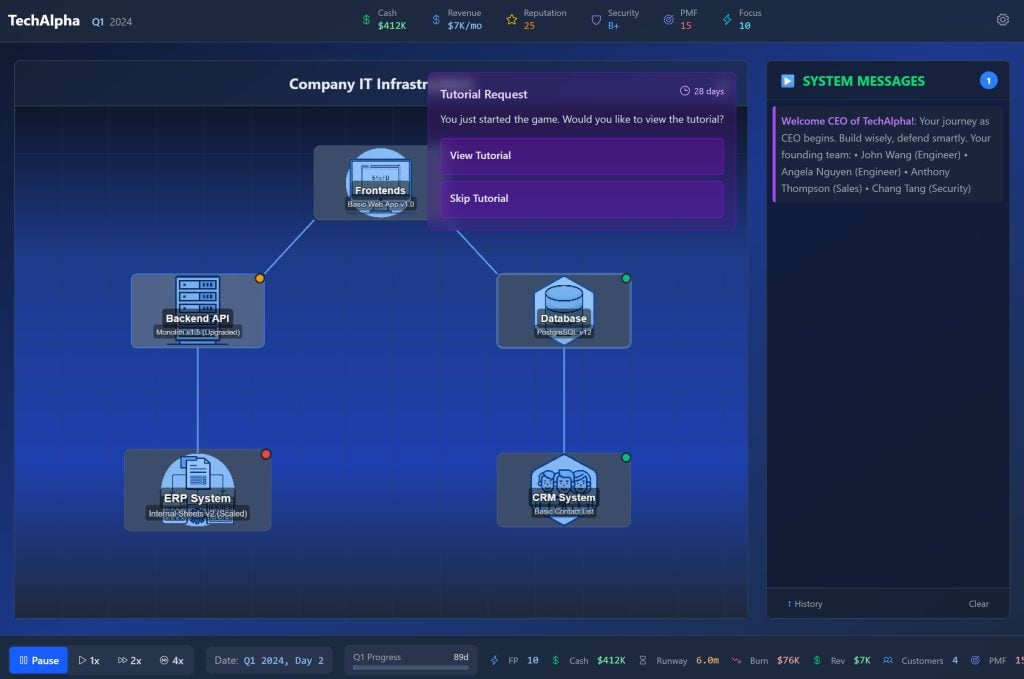

CISO Challenge is a real-time simulation where you play as the CEO of a growing company. You have a product, a sales team, and product-market fit. You need to acquire customers and improve your offering to go after larger deals. But as you become more successful, you become a more compelling target.

Adversaries will run phishing attacks, scan your environment for vulnerabilities, attempt remote code execution, and even try to bribe employees for insider access. You have to decide how to allocate resources: Hire more salespeople, more engineers, or more security staff? Invest in infrastructure security improvements that come with costs? Focus on product-market fit versus operational efficiency?

Success is measured simply: Does your company survive? Or do you go under because you run out of money or suffer a critical security compromise that puts you out of business?

The game has two modes. You can play as the CEO making these tradeoffs, or you can play as the adversary, getting more sophisticated, targeting companies, stealing data, and extorting victims to maximize your profits.

The game is currently in early development. I estimate it will take another three months to get to a first playable version. More updates will definitely come as it progresses.

Practical takeaways

For security professionals: It’s very common to do a risk assessment and then work on the top identified risks with available resources. Security invariants open up a different perspective: attack surface elimination.

Some of the invariants you can find on securityblueprints.io are actually fairly straightforward to implement. You should consider implementing them or at least becoming aware of them and starting to build organizational consensus toward deploying them. Rather than just mitigating risks, you can categorically eliminate entire classes of attacks.

For company leaders: The rational choice today is often to underinvest in security. But that calculation is based on the current incentive structure. As regulations tighten and the costs of breaches increase, that mathematics will change. Getting ahead of that curve means understanding security invariants now and building them into your infrastructure from the beginning rather than retrofitting them later at much higher cost. Ask your teams how they’re systematically addressing entire attack surfaces, not just individual point risks. More importantly, ask what systems are in place to prevent security regression. You need principled solutions that make certain risky patterns impossible, ensuring that as you work through existing tech debt, no new problems in those areas accumulate.

Where do we go from here?

The analysis of 70 data breaches revealed something that should fundamentally change how we think about security: 65% of breaches are preventable with just three invariants. This isn’t about better risk mitigation. It’s about attack surface elimination. Instead of managing endless lists of vulnerabilities and buying dozens of point solutions, we should be asking which entire classes of attacks we can categorically prevent.

But data alone doesn’t change behaviour. The real barrier is incentives. Companies are rational actors, and in today’s environment, the rational choice is often to underinvest in security. Until the incentive structure changes — through tougher regulation, insurance requirements, or a fundamental shift in how we calculate security ROI — we need new approaches to make the tradeoffs visceral.

That’s why I’m building CISO Challenge: To help leaders and security professionals experience these decisions firsthand, to see how companies flourish or fail based on their choices, and to demonstrate that security and growth aren’t opposing forces when you build on the right foundation from the start.

We’re all on this journey together, and there are no shortcuts. Over the next three months, I will be building a playable prototype of the CISO Challenge. It’s a small step, but one I hope will give leaders a new, more visceral way to experience the choices and consequences that define modern security.

Niels Provos is a computer security practitioner with a PhD in computer science from the University of Michigan. His career includes roles at Google, Stripe, and Lacework. With over 15 years of experience as a people manager, Niels is dedicated to fostering well-executed and healthy teams.

Originally published on Security Blueprints.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.