The first part of this report looked at the size of the routing table and some projections of its growth for both IPv4 and IPv6. However, the scalability of BGP as the Internet’s routing protocol is not just dependent on the number of prefixes carried in the routing table. Dynamic routing updates are also part of this story. If the update rate of BGP is growing faster than we can deploy processing capability to match, then the routing system will lose coherence, and at that point the network will head into periods of instability.

This report will look at the profile of BGP updates across 2021 to assess whether the stability of the routing system, as measured by the level of BGP update activity, is changing.

IPv4 stability

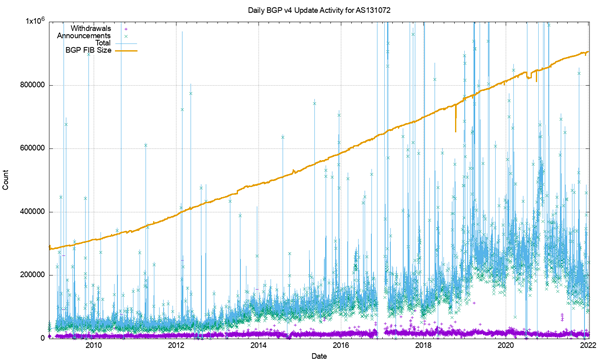

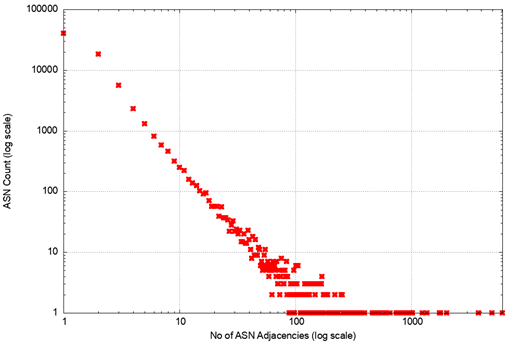

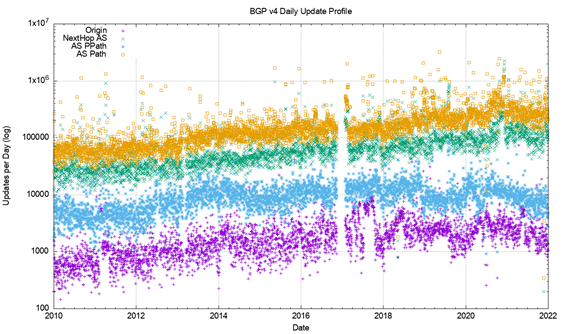

Figure 1 shows the daily BGP update activity as seen at AS131072, since mid-2009.

The number of observed BGP withdrawal messages per day (shown in violet in Figure 1) has remained relatively constant at 15,000 – 20,000 withdrawals per day, while the number of advertised IPv4 prefixes has risen from 300,000 to 900,000 (shown in orange in Figure 1). There is no particular reason why the daily withdrawal count should be steady while the number of announced prefixes has tripled. If withdrawals are a result of some form of link-based isolation event at the origin, then we would expect that as the number of networks increases the withdrawal volume would also increase proportionately, but this is not what we see in BGP. The withdrawal rate also appears to be unrelated to either the number of routed prefixes or the number of routed networks.

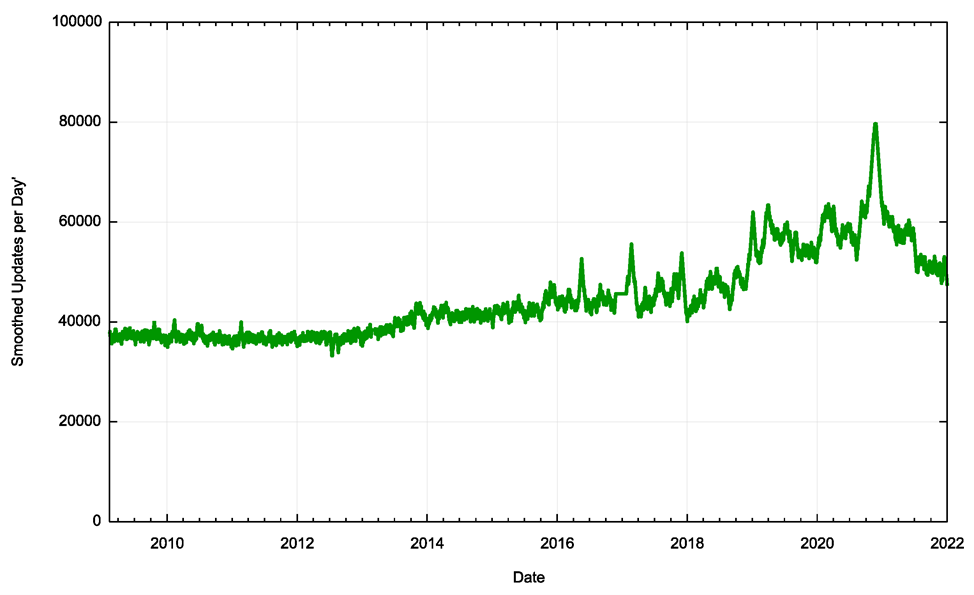

The number of update messages per day (shown in green in Figure 1) has not been as constant. This was steady at 35,000 updates per day from 2009 until 2013. During 2013, the volume of updates grew to 42,000 updates per day, which it maintained for most of the ensuing 24 months. During 2018, the number of updates per day rose again, approaching 60,000 updates per day by the end of 2018. The update count remained around this level until the start of 2021. Throughout 2021, the update rate has declined to an average value of around 50,000 updates per day. To illustrate these trend movements in the BGP update rate, a smoothed average of the daily update count is shown in Figure 2.

It has been fortuitous that the BGP update rate had been held steady for so many years, as this implied that the capability of BGP systems did not require constantly increasing processing capability. In the same way that there was no clear understanding of why the BGP update rate was steady for so many years, it’s also unclear why the rate increased and then declined in recent years.

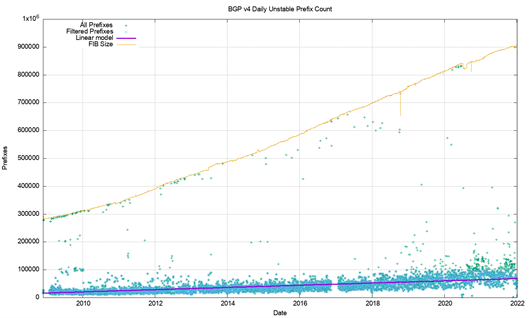

What is also intriguing is that most of these prefix update messages are generated from a pool of between 30,000 to 80,000 prefixes. A daily count plot of prefixes that are the subject of BGP updates is shown in Figure 3. While this number is rising, it is not rising at the same rate as the number of updates per day, so the heightened instability is possibly due to more updates reaching convergence, rather than due to more unstable prefixes. Another possible explanation is that we are looking at daily average numbers, and this rise in the average could be caused by a small pool of unstable prefixes exhibiting higher levels of instability than was the case previously.

The number of unstable prefixes per day appears to be gradually increasing over the years. A least-squares best fit shows a linear trend where the average daily unstable prefix count is increasing by 3,800 prefixes per year. This is far lower than the trend in the increase of the Forwarding Information Base (FIB) table size.

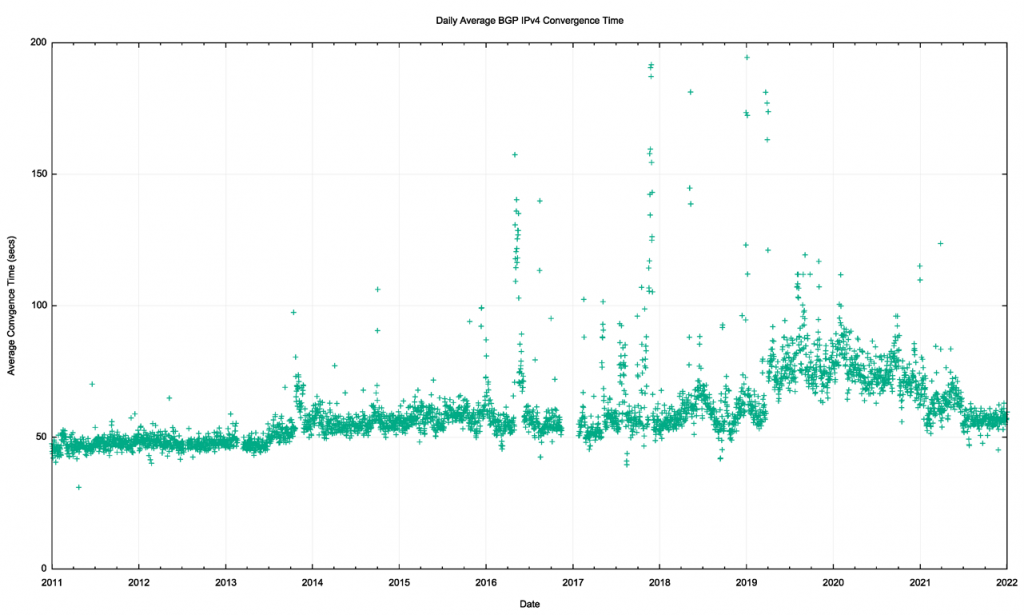

However, this increased count of unstable prefixes and the increasing update count is not reflected in the measure of the time to reach a converged state (this is the period for the routing protocol to reach a converged state for an updated prefix). The average time for an unstable prefix to reach stability is still at some 50 – 60 seconds (Figure 4). There was a period of elevated instability during 2019 – 2020 where the average convergence time rose to 80 seconds, it has since stabilized to a time of 60 seconds for the latter half of 2021.

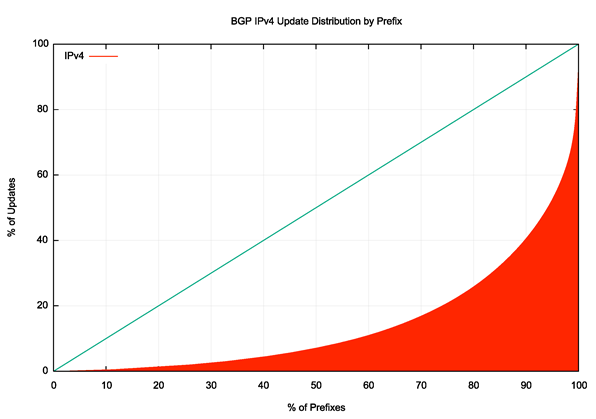

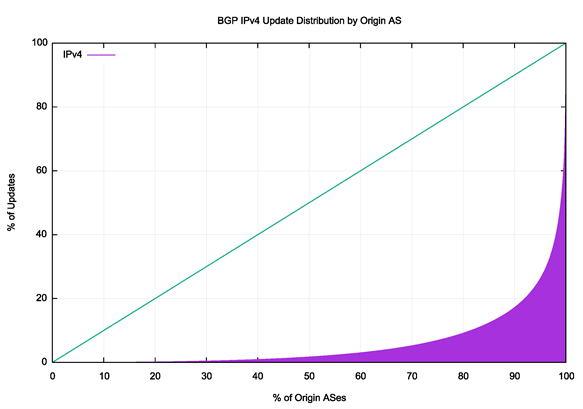

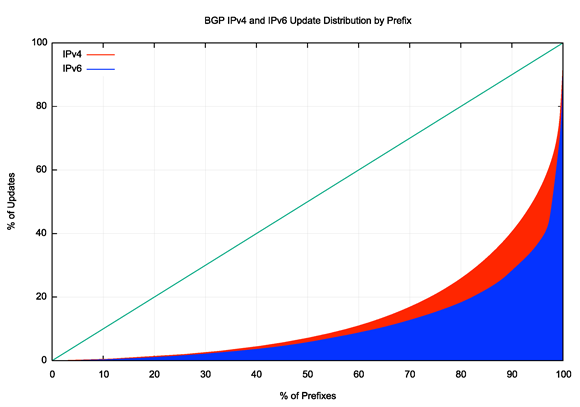

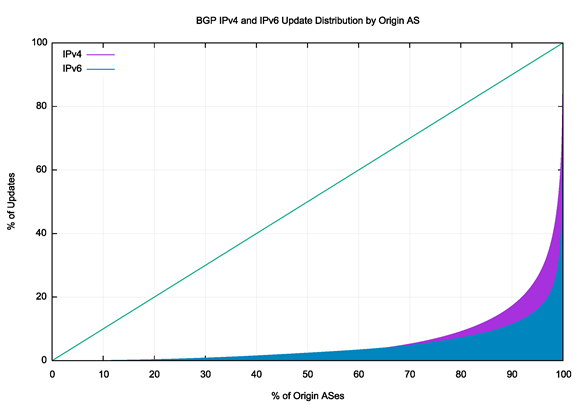

The instability in BGP is not uniform. Half of all BGP updates during December 2021 are attributed to less than 10% of the unstable prefixes, and just 50 origin Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs) accounted for one-half of all BGP IPv4 updates in this period. It appears that the network is generally stable, and that a very small number of prefixes appear to be advertised with highly unstable BGP configurations over periods that extend for weeks rather than hours. The cumulative distribution of BGP updates by prefix and by origin AS, represented in Figures 5 and 6, shows the highly skewed nature of unstable prefixes in the routing system. It’s also interesting that the ASN distribution is more ‘skewed’ than the prefix distribution. This would tend to suggest that cases of high update volume are generated at the AS level rather than the prefix level.

IPv6 stability

Ideally, the IPv6 routing network should be behaving in a very similar manner to the IPv4 environment. It is a smaller network, but as the overlay IPv6 tunnels are phased out, the underlying connectivity for IPv6 should be essentially like the connectivity of IPv4 (it would be unusual to see two networks where one provided transit services to the other in IPv4, yet the opposite arrangement is used for IPv6). So, given that the underlying topology should have strong elements of similarity across the two protocols, we should see the BGP stability profile of IPv6 appear to be much the same as IPv4.

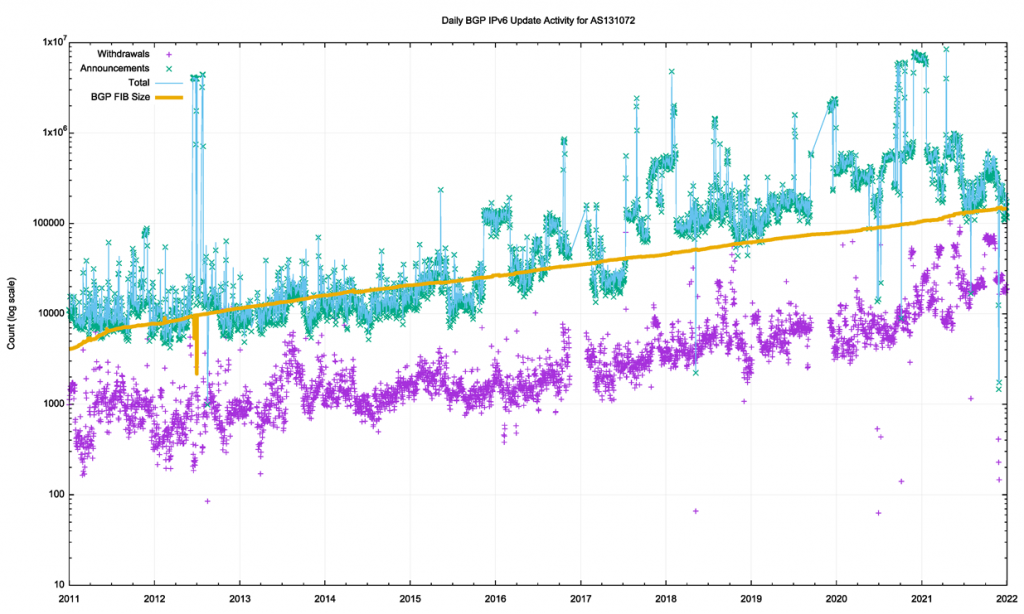

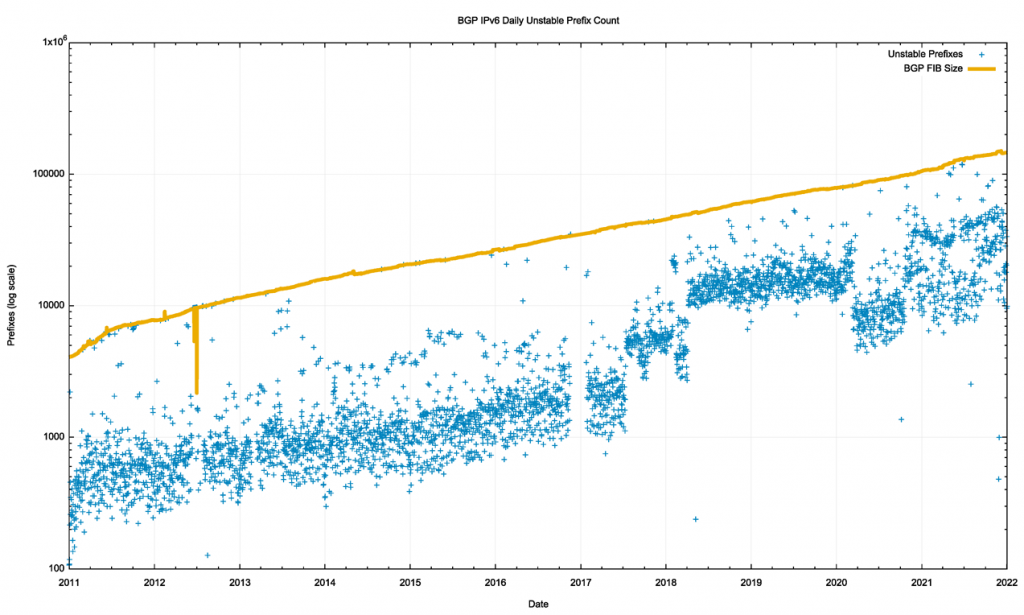

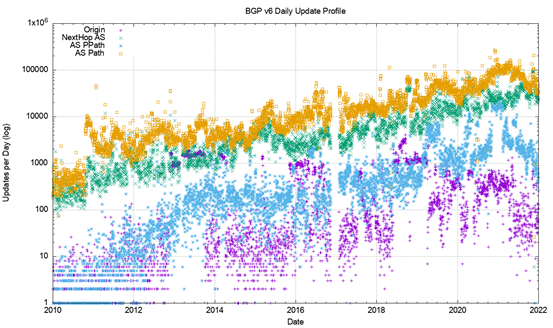

However, this is not the case. Figure 7 shows the profile of IPv6 updates since 2011. The IPv6 BGP network appears to be far ‘noisier’ than the IPv4 network. The number of withdrawals and updates appears to follow the IPv6 FIB table’s total size. This shows some pathological instability in parts of the IPv6 network that may be due to some form of BGP route oscillation failing to converge.

Figure 8 shows that the number of unstable prefixes has changed since the start of 2018. From 2011 until the start of 2018 the number of unstable prefixes was tracking the total IPv6 table count, with 10% of announced prefixes being updated each day. This jumped to 20% at the start of 2018. The high count of updated prefixes suggests a topology-based oscillation in one of the upstream feeds for this network that appears to affect a large subset of the total count of prefixes in the IPv6 routing table. This instability was partially addressed in 2020 but has since returned in the latter months of 2020.

An issue with running two discrete routing systems within the Internet is that it is sometimes the case that operational attention remains fixated on the IPv4 routing system, while IPv6 is simply assumed to be working. Routing pathologies in the IPv6 network appear to remain unnoticed for many months, and at the end user level the dual-stack environment simply masks the issues. Failure to connect in IPv6 is silently fixed in dual-stack applications’ Happy Eyeballs mode by rapidly switching to use IPv4 for the affected sessions when IPv6 reachability is impaired in some way.

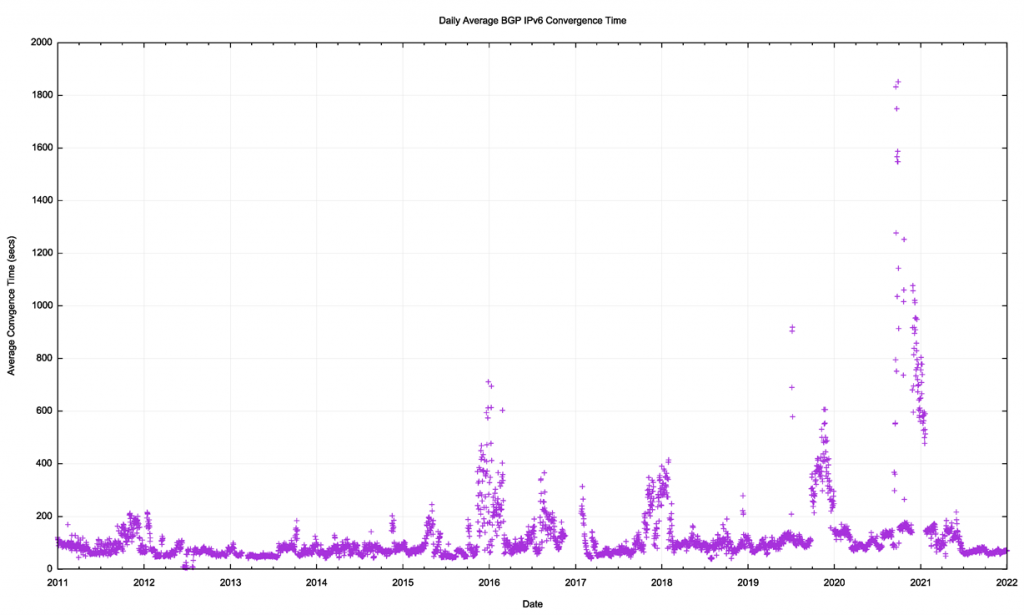

The average time to reach convergence has been unstable for the IPv6 network (Figure 9). The daily average of this convergence time ranges between 70 and 100 seconds. The last half of 2021 saw periods of high instability with protracted average times of up to 1,800 seconds to reach convergence for individual prefixes. The last six months of 2021 has improved considerably, with an average measurement of 70 seconds for the routing system to reach a stable announcement for an updated prefix.

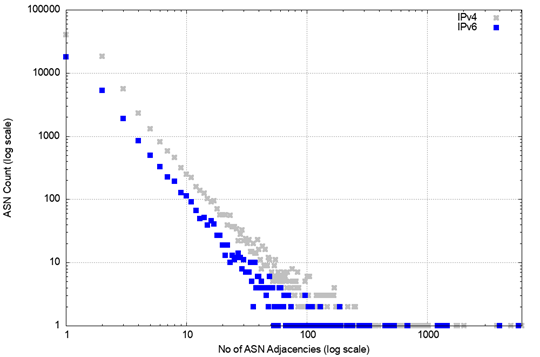

It is also evident that the distribution of updates across the set of announced prefixes and originating ASNs is more skewed than IPv4. In December 2021, the most unstable 10% of IPv6 prefixes accounted for 60% of the total update volume, and the most unstable 50 Origin ASNs accounted for some 80% of the updates. The distribution of updates in IPv4 and IPv6 is shown in Figures 10 and 11.

It is not immediately obvious why IPv6 has a higher instability component than IPv4. A concern is that this instability remains a persistent condition as the IPv6 network continues to grow, creating a routing environment that imposes a higher processing overhead than anticipated, with its attendant pressures on BGP processing capabilities in the network.

Instability and topology

BGP is a distance vector routing protocol that achieves a coordinated stable routing state through repeated iterations of a local update protocol. The protocol efficiency depends heavily on the underlying network topology. Highly clustered topologies, such as star-based topologies, will converge quickly, whereas arbitrary mesh-based topologies will generally take longer to converge to a stable state.

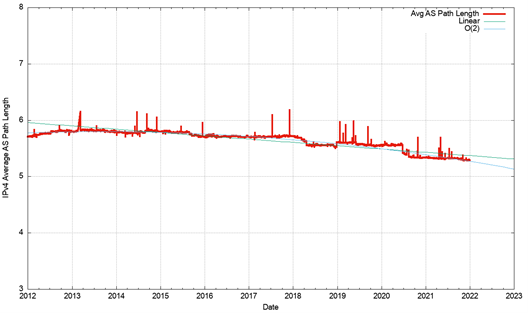

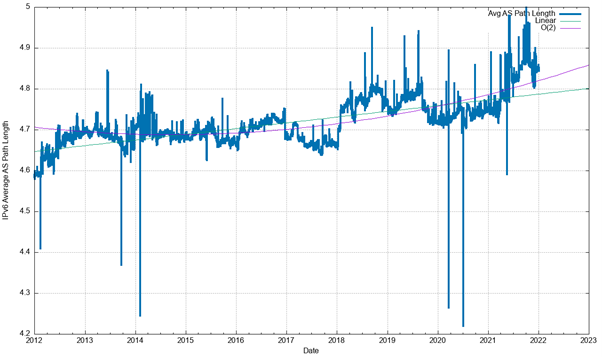

The convergent behaviour of BGP, particularly in the IPv4 network, is quite remarkable and perhaps the best illustration of why this is the case lies in the average AS path length of the BGP routing table over time (Figure 12).

A related picture is shown in the distribution of AS adjacencies counts in the IPv4 network (Figure 13). Only 14 networks have more than 1,000 AS adjacencies that are advertised into the transit network. This is consistent with a network that is composed of a relatively small set of transit ‘connectors’ and a far larger set of stub networks that attach themselves into this core.

A similar picture exists in IPv6 (Figure 14) of a relatively stable average AS path length, and there is a similar picture of AS adjacency distribution (Figure 15). In the case of IPv6, there are other factors that appear to influence the overall stability of IPv6.

These profiles of topology would support a conclusion that the IPv4 and IPv6 BGP systems should behave in a reasonably similar manner, yet IPv6 is visibly less stable.

However, the distributions of Figures 10 and 11 need to be remembered. When we are talking average update volumes, we are actually talking about a very small set of prefixes that generate anomalously high numbers of updates. When we say ‘IPv6 is visibly less stable’, it is probably more accurate to say that ‘the small number of anomalously unstable prefixes in IPv6 exhibit relatively higher levels of instability than their IPv4 counterparts’.

Instability and update types

We can look further into these updates to see if there is any visible correlation between routing practices by network operators and BGP instability. If we only look at updates that refine an already announced address prefix, then we can use a taxonomy of the effect on the routing update. The taxonomy used here is to look at a change in the origin AS, a change in the next hop AS (the next AS in the AS path that is adjacent to the origin AS), a change in the AS prepending of the AS path, any other changes in the AS path, and finally a change in the non-AS path attributes of the update.

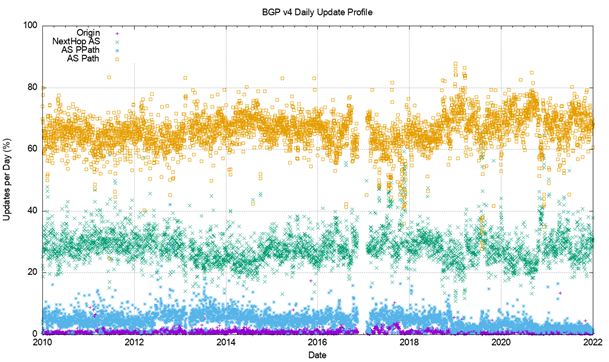

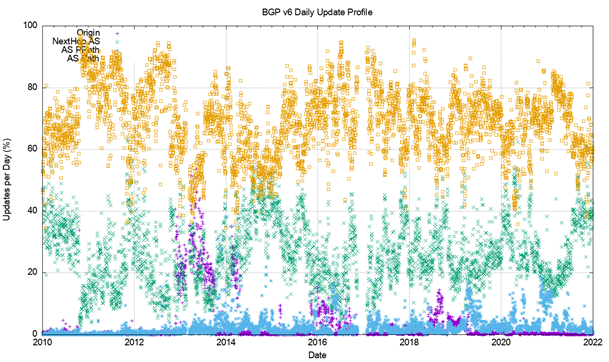

The daily count profile of these updates for IPv4 is shown in Figure 16 for IPv4. Changes to origination of prefixes is uncommon. The most common changes are related to internal topology changes in the network (AS path change) and changes in stub-to-transit connections (AS next hop), which is, presumably, often related to traffic engineering changes.

A similar profile is visible in the IPv6 network with AS path changes and AS next hop changes being a major part of the update profile. In absolute terms, the volume of path change and next hop changes are comparable, and sometimes greater than the IPv4 measurements. Don’t forget that the IPv4 routing table had 1M entries in recent months compared to the 150,000 entries in IPv6, so this instability of IPv6 network topology is up to six times greater than IPv4 on some days!

Another way of looking at this data is to remove the absolute volume of updates and look at the update types as a proportion of the total number of updates seen each day (Figures 18 and 19).

In IPv4, most (70%) of the BGP updates describe changes in the AS path. Slightly less than 30% of the changes occur with the next hop AS. IPv6 shows a similar update profile.

Much of this instability is likely due to BGP oscillation when negotiating routing policies relating to multiple paths. As a distributed algorithm, BGP itself is not a deterministic process, and when the protocol is attempting to negotiate a stable outcome between the BGP preferences of BGP speakers announcing reachability across multiple egress paths, and BGP listeners applying local preferences across several ingress paths, then some level of instability is not unexpected. Perhaps most surprising is that these BGP updates are so low, particularly when the underlying topology appears to show such a rich level of interconnection. When a BGP environment becomes unstable and flips between multiple equivalent local states, we might expect that the BGP update rate would increase uncontrollably. But BGP’s Minimum Route Advertisement Interval (MRAI) damping interval mitigates this situation. BGP will only emit updates every MRAI seconds, and only pass on the current state of each updated prefix at that time, damping out any form of higher frequency local route oscillation. The commonly used value of 27 – 30 seconds (varied randomly each MRAI interval) is the most likely explanation of why BGP appears to be so well behaved in terms of update rates.

The cost of this MRAI timer is reflected in the average time to route convergence, which is steady at 50 seconds in IPv4 (Figure 4) and varies between 50 and 300 seconds in IPv6 in a long-term oscillation with a period of months (Figure 9). This is of course far longer than the 50ms ‘ideal’ time to converge. 50ms is commonly cited as ideal within the industry (although why the value of 50ms has been chosen is baffling, as there is no known justification for this value). Occasionally, discussion takes place on reducing the MRAI timer value for all eBGP speakers, as that change could possibly result in faster average convergence times. However, the relationship between MRAI timer settings and overall BGP update volumes is not so clear. It is likely that the widespread use of a smaller MRAI timer in the eBGP environment would result in an increased volume of BGP updates.

Instability and traffic engineering

BGP is used for two functions. The first is the maintenance of the network’s inter-domain topology. BGP ‘discovers’ the set of reachable networks through the conventional operation of a distance vector-style distributed routing protocol. It’s not that every BGP speaker assembles a complete connected state map of the network, BGP’s objective is slightly different. Each BGP speaker maintains a list of all reachable address prefixes and for each prefix maintains a next hop forwarding decision that will pass a packet closer to its addressed destination.

The second part of the use case can be more challenging. BGP is used to negotiate routing policies, or so-called ‘traffic engineering’. If a network is connected to two upstream transit providers and one offers a lower price than the other, then the local network may prefer to use the lower cost network for all outgoing traffic, all other things being equal. Incoming traffic also needs to be considered — the local network operator may like to bias the route selection policies of all other networks so that the lower cost transit network is used to reach this local network. Outgoing traffic can be groomed to match local policies by using local policy settings in the interior routing space, but incoming traffic can only be ‘groomed’ using BGP to bias other networks’ route selection policies. There are a number of ways of achieving this, but the basic observation is that if you wish to groom incoming traffic according to a number of different policy settings then you need to advertise a collection of address prefixes to be associated with each policy setting. The most common routing practice is to advertise the aggregate route set to all adjacent peers, then selectively advertise more specific routes to some adjacent peers to implement these routing policies. In this scenario, we would expect to see the aggregate routes and the more specifics have differing AS paths, but they would share the same origin AS.

A variant form of traffic engineering exploits the BGP route selection algorithm’s preference for shorter AS paths, when all other factors are equal. A BGP speaker may elect to artificially increase the AS path length on the less preferred ingress path by adding repetitions of its own AS to the AS path of the less preferred eBGP peer. Any form of instability in path selection between these multiple ingress paths would be reflected as a set of updates that retain the same origin AS, the same next hop AS, and retain the same sequence of ASes in the AS path. But the paths would differ across successive updates in the amount of AS prepending contained with the path.

A different scenario occurs when an end site uses an address prefix from a provider’s address block but wants to define a unique routing policy. In this case, the end site would use its own AS number, so that the aggregate and its more specific would use different origin AS numbers.

It is also possible that the network operator is advertising more specific routes as a means of mitigating (to some small extent) the impacts of a hostile route hijack. In this case, the aggregate route and the more specific route would share a common origin AS and a common AS path.

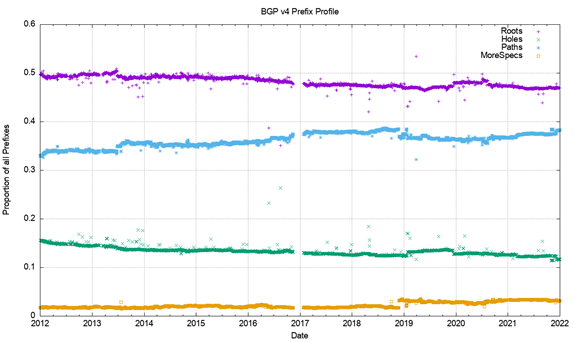

We can look at the routing table to see the prevalence of each type of advertised prefix. Figure 20 shows the relative prevalence of these four types of route advertisement:

- Root prefix, which has no covering aggregate

- Hole prefix, where the origin AS of the more specific prefix differs from the origin AS of the covering aggregate

- Path prefix, where the more specific prefix shares the same origin AS, but has a different AS path

- More specific prefix, where the AS path of the more specific and the covering aggregate are the same

Over the past six years, the proportion of root prefixes has declined slightly, as have hole prefixes, while the number of path (different-path more-specific) prefixes has risen slightly. The high proportion of path prefixes points to a prevalent use of more specifics in the IPv4 network for traffic engineering purposes.

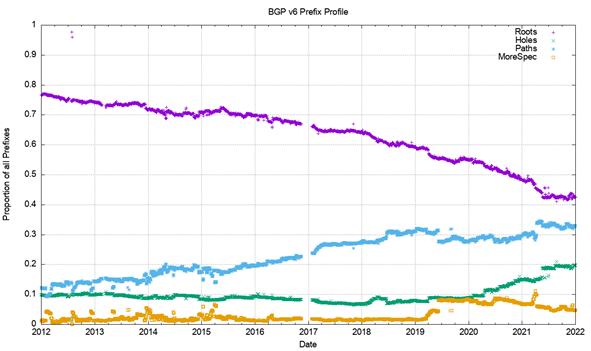

A comparable view of the IPv6 network (Figure 21) shows a similar result, but some different starting conditions. The relative incidence of root prefixes has declined from 95% to 40%, while the number of path-distinguished more-specific prefixes has risen from 10% to 35%. A possible explanation is that as IPv6 changes from being a low-use trial to becoming part of the service environment, traffic engineering rises in importance. The number of different-path more-specifics reflects this changing perception of the IPv6 network’s role. The relative count of IPv6 hole prefixes has doubled in the past two years.

This data reflects the emerging picture of handling IPv6 addresses in a similar way to IPv4, where there is widespread use of more specifics for both traffic engineering and as a rudimentary form of anti-hijacking defence.

Are each of these prefix types equally likely to be the subject of BGP updates? Or are some prefix types more stable than others? An intuitive guess would see root prefixes being more stable than traffic engineering prefixes, as would the hole-punching more specific prefixes. The other two types of more specific prefixes should be more likely to be unstable.

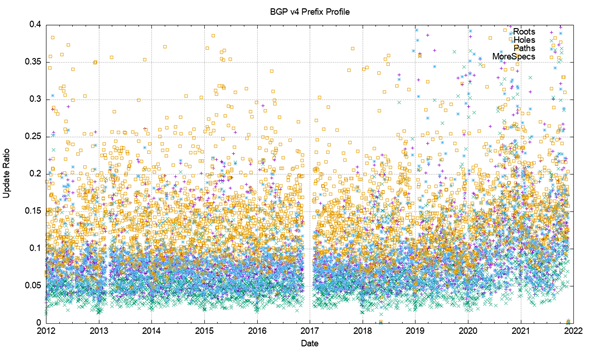

Figure 23 shows the day-to-day calculation of the relative proportion of BGP instability. It plots the number of updated prefixes per day of each prefix type, compared to the total prefix number of that type. It is a relatively noisy picture, but some general trends are visible. More-specific prefixes that have the same AS path as their covering aggregate are more likely to be updated when compared to other prefix types. Root prefixes and path prefixes (more specifics with different AS paths) appear to have a similar update ratio. Hole-punch more specifics (different origin AS) are the most stable of the prefixes in the IPv4 network.

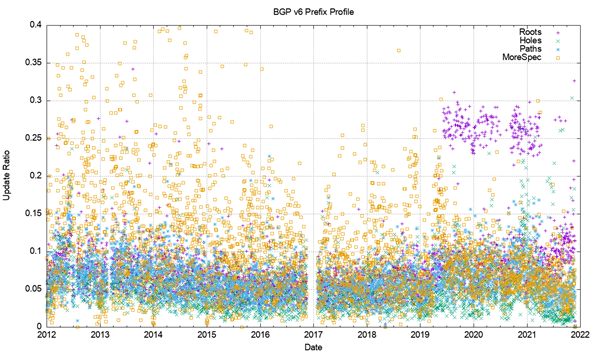

The same analysis has been applied to the IPv6 network (Figure 23). A similar picture is evident in the data, but the level of day-to-day variation is far more evident. Interestingly, 2019 saw a sharp rise in the instability of root prefixes, which has remained the case for much of the time in the ensuing two years.

Conclusions

None of the BGP churn metrics indicate that we are seeing such an explosive level of growth in the routing system that it will fundamentally alter the viability of carrying a full BGP routing table anytime soon.

BGP update activity is growing in both the IPv4 and IPv6 domains. The ‘clustered’ nature of the Internet, where the growing network’s diameter is kept constant while network density increases, implies that the dynamic behaviour of BGP — as measured by the average time to reach convergence — has remained very stable in IPv4 and bounded by an upper limit in IPv6.

The frequency of BGP updates appears to be largely unrelated to changes in the underlying model of reachability, and more related to the adjustment of BGP to match traffic engineering policy objectives. The growth rates of updates are not a source of any great concern at this point.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.