Or, for that matter, where am I? Let’s look at location on the Internet, and how the Internet ‘knows’ where I am.

With devices that have Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) enabled, such as my mobile device, ‘where am I?’ is an easy question to answer. If my device has a good view of the sky, then it can report its position to an accuracy of within five metres or so these days. If I want to be more precise, then I can use techniques such as Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) position to get to an accuracy of a centimetre or so with the use of a nearby reference point and specialized equipment. Even without centimetre accuracy, just knowing where I am, even within a meter or so, is great sometimes. It’s great when I’ve attached a tag to my keys and then misplace my keys! Or my luggage. Or when I’m lost in a new location.

However, location is also used in many other contexts. For example, on 10 December 2025, a new restriction was applied in the economy where I live, Australia, where people who are under 16 years of age cannot operate certain social media accounts. That raises two questions about me: What is my age? And am I in Australia?

The first is a topic for a different time, but the second question is another way of asking the location question. This time, the answer to that question does not necessarily demand a high level of precision, but the essential task for the social media operator is to map my location to a point on the geopolitical map of the world to see if I am within Australia’s territorial boundaries or not. On my mobile device, with a clear view of the skies above, the Global Positioning System (GPS ) can do the job very competently, but what about the location of my other devices, where GPS is not available? And in this case, it’s my location that is important in order to comply with this legislation. The social media operator has a requirement to know where I am, at least in terms of ‘is my location within the territory of Australia or not?’

This generic activity of locating devices and users, termed ‘Geolocation’ or ‘Geoloc’, was the topic of a workshop, hosted by the Internet Architecture Board (IAB) in early December 2025, and here I’d like to relate my impressions from the discussions that took place in this workshop.

RFC 8805 — IP geolocation

In the days of the fixed wire telephone network, an E.164 telephone number was assembled from a set of location-based fields. The full telephone number starts with an economy prefix. All numbers starting with CC of 61, for example, are ‘located’ in Australia. The next set of digits is typically an area code. Although the size of this code varied between economies, regions within an economy shared a common area code. Within an area, there was often a discernible structure, so subscribers located in an area bounded by an individual central office switch would share a common intra-area code prefix.

Could we use IP addresses in the same way we used telephone numbers, and derive an approximate location from the value of the address itself? Is there a way to ‘map’ an IP address to establish the location of the device that is using this IP address? This is not straightforward, as, unlike telephone numbers, there is no explicit hierarchy in IP addresses that would lend itself to the derivation of location. That does not mean that you can’t use an IP address alone to derive a location, as you need some form of an associated ‘map’ that can translate an IP address to a location.

These days, the most common format for feeding data into a location ‘map’ is specified in RFC 8805.

The motivation to adopt this standard format for mapping an IP address to a location was the increasing use of IPv6 in the public Internet some 20 years ago. At the time, there were several sources of maps for geolocating IPv4 IP addresses, but no equivalent map existed at the time for IPv6 addresses. One of the early consumers of this location data was Google’s search engine, which used the IP address of the querier to establish a location context for likely responses. For example, if a user queried for ‘pizza shop’, Google’s search system used the location information of the querier to trigger a search for ‘pizza shop near my location’ and generated responses that matched both the content of the original query (pizza shop) and its assumed context (near my location).

There were several IPv4 location maps at the time, typically distributed under commercial terms. These address maps were constructed from the base data published by the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs), whose databases associated IP address prefixes with economies, and then further refined with data gathered from other sources, including ping and traceroute, to infer a locational association between addresses. At the time, there were no IPv6 location maps, and one way to rapidly bootstrap this IPv6 location data was to detect instances where a user had both an IPv4 and an IPv6 address, and the IPv6 address location could be associated with that of the IPv4 address.

However, this form of location mapping was little more than piecemeal guesswork. Informed guesswork to be sure, but it still was lacking some form of ‘ground truth’. Internet Service Providers (ISPs) were encouraged to publish geolocation maps of the IP addresses used within their networks. This allowed others to regularly collect that data and combine individual ISP feeds into a broader geolocation database, covering most IPv4 and IPv6 addresses in use at the time. ISPs were motivated to provide location information because it enhanced the experience of their customers. Content providers could use this data to apply default local languages, localize content, and comply with regional regulations. Additionally, location information helped improve user security, for example, by detecting attempts to access accounts from non-local locations.

RFC 8805 defines a simple text file, formatted as either CSV or XML these days, with each record describing a single address prefix with a set of location descriptors: ip_prefix, alpha2code, region code, city name, postal_code. The alpha2code is the ISO-3166 two-letter CC, and the region code is the ISO-3166-2 region code. The code for the city name doesn’t conform to any standard specification or language, as no such single standard exists, and the postal code is now deprecated. (In some economies, notably the United States, the full zip code is a five-digit field for a city and a four-digit extension that adds specific detail, such as a city block, or even a single entity if they receive a high volume of mail. The potential for high precision of postal codes creates a tension with personally identifying information, and for this reason, postal codes have been deprecated from use.)

It is now a common practice for network operators to publish this data about the location of their clients who have been assigned an IP address using this RFC 8805 format, and provide a pointer to the publication point of this data in their database record with the RIRs, using the geofeed: attribute of inetnum data objects in the RIR databases.

There is the issue of knowledge and consent, particularly where quite specific location data is being used, which may narrow down the set of clients encompassed by the location data. As RFC 8805 points out: “Operators who publish geolocation information are strongly encouraged to inform affected users/customers of this fact and of the potential privacy-related consequences and trade-offs.”

There is also a follow-up document, RFC 9632 (Finding and Using Geofeed Data), that specifies how to augment the Routing Policy Specification Language (RPSL) inetnum: class to refer specifically to these RFC 8805 geofeed files by URL. This specification also describes an optional scheme that uses the Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) to authenticate these geofeed files.

The use of RPKI is interesting, as it is a response to address an aspect of the authenticity of geolocation information. The concept behind these geofeed signatures is that the address holder can use their private key to sign a geolocation entry, asserting that they have some legitimacy in attesting to the location of that address, as well as allowing the user of the file to validate the completeness of the report as a replica of the originally published data. However, it does not directly address the veracity of the location information.

This work was informed by the IETF’s GEOPRIV Working Group, a group that was focused on defining IETF standards for handling geographic location information securely and privately within Internet protocols, creating frameworks for location-aware applications, and real-time communication while keeping the development of core location discovery technology out of scope. The Working Group published RFC 6280 (Architecture for Location/Privacy) and RFC 5870 (geo URI), establishing common formats, APIs, and protocols (like HELD) for location sharing, ensuring privacy was integral to location data management.

Of course, location has many other implications beyond figuring out nearby pizza shops. Harking back to Google’s search engine, some results are not permissible in certain economies, which would affect searches for any sensitive terms. This does not necessarily prevent a multi-national service platform, such as Google, from assembling pointers to such content, but it does restrict the presentation of such pointers to end users, based on the assumed location of the user.

There is also the consideration that many economies have quite unique web cookie management policies, entailing a customization of application behaviour to match local policies based on the assumed location of the user’s device. It does strike many folk, including myself, who find it oddly bizarre that we are being asked for specific directions about management of these cookies via popups when I visit certain websites, without any broad understanding of precisely what is being asked for, why, or what granting or denying such permission may imply for my experience as a service client or my personal privacy! It seems to me that this is a classic misapplication of the concept of user consent, where a user is being asked to provide consent over an action over which they have no competent understanding relating to what such consent implies!

So far, I have described the exercise as one that relates to the location of a user by assuming that the location of the user is much the same as the location of the device that they are using. There are various forms of remote device access tools that allow the user and the device that they are using to be arbitrarily distant, and in general, the assumption behind user location through device location ignores the possibility that these two locations might be distinct.

There is also the consideration of ‘teleportation’ tools, such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and similar forms of relay tools, where the location of the interface to the public Internet is different to the location of the user’s device. To any onlooker or service provider, the user’s device appears to be located at the tunnel egress point to the extent that its appearance is indistinguishable from any other device that is physically located at the same tunnel egress point.

What appears to be lacking here is a consistent ontology about the meaning of ‘location’, relating to the location of network infrastructure equipment that acts as a tunnel endpoint, the location of the device and the location of the user. In an aircraft on an international flight, a passenger is ‘located’ in the jurisdiction of the economy of the aircraft’s registration, irrespective of the precise location of the aircraft. In ships at sea, the jurisdiction of the economy of the vessel’s registration is only used when the vessel is physically located in international waters.

A perspective from a geolocation provider — MaxMind

A commonly used tool for IP geolocation is the MaxMind data. MaxMind publishes a geolocation data set that maps IP addresses into economies, and a more detailed data set that provides a similar mapping to a state and city level. The approach used by MaxMind is to gather a variety of sources about the location of an IP address, starting with the data set provided by the RIRs, geofeeds, PeeringDB, and ancillary data that can assist in the triangulation of location.

The RIRs publish data relating to the allocation and assignment of IP addresses to network providers and other intermediaries. The registries contain the names of these organizations and their addresses, including a CC. This address is not necessarily the address where the addresses will be used, nor is the size of the address block the size of the announced prefix in the routing system. It’s the holding organization’s address. However, in the absence of any other signal, this economy code in the RIR data is as good a starting point as any to assemble a geolocation map.

From this starting point, it’s possible to refine this view. If a network publishes a geofeed, then this is a useful signal for a specific set of address prefixes. The routing system can also be used in that if the location where an Autonomous System Number (ASN) is being used is known, then this implies that the location of all the IP addresses that are originated by this AS can also be derived, in that their location is bounded by the AS’s usage bounds.

There is other third-party bulk data, particularly relating to areas of the world where the location service provider is not well-resourced to be able to perform the data gathering and analysis directly. There is traceroute and ping data, which can assist in triangulation exercises, and there are reverse DNS names, which often incorporate geonames such as airport codes, particularly when naming infrastructure elements. There are also individually notified amendment requests, where more specific location information is submitted to the location service operator. This data is fed into a set of heuristics and preference rules to create confidence assessments and conflict resolution, which is used to come up with a location result for all routed IP addresses.

Part of the challenge of this work is that IP addresses don’t necessarily have a simple, single view of the location where the address is being used. There is a (sometimes subtle) distinction between the location of the individual using the device, the device’s location and the location where the traffic enters and leaves the public Internet. This is significant when the device is connected by a VPN or a relay, or when the user is using a remote access tool. MaxMind’s priority is to geolocate the person who is using the device (which could explain the large number of IPv4 prefixes smaller than an IPv4 /24 in the MaxMind data set).

MaxMind are also looking to expose their confidence intervals relating to the location of observed traffic. Generally, observed network traffic for a prefix lies in a single locale, although there are signals of traffic use across larger locales reflecting mobile use and business and residential use of VPNs. The aim here with the exposed confidence level is to provide greater transparency of the calculations that result in a single line ‘best estimate’ location.

What about the consumers of MaxMind’s data and location data in general? When you ask ‘Where is this IP address located?’ there is a regulatory location, which attempts to identify which regulations or content access constraints (Digital Rights Management (DRM)) must be are applied to an individual user at a physical location, as compared to a network location which attempts to decide between potential servers to optimize service performance between server and user device for the transaction, which is optimized against this network location. Compounding this is the desire to perform both regulatory and network location at once from a single location signal.

Consumers of this location data tend to have different requirements from location. The DRM and regulatory compliance activities tend to seek the most precise location that it’s possible to obtain, and to do so with the most recent data that is possible, to avoid misapplication of these location-based constraints. Ad placement technology is concerned more with demographics and coverage. High precision location is relevant only to the extent that it can inform a demographic indicator (such as working in a particular sector or attending a university campus). There is also the security perspective, where location data can be used to identify anomalous transactions that are potentially fraudulent.

In the case of IPv4, and also increasingly in IPv6, there is the issue of shared addresses, where a single public address may be shared between multiple users, either serially or simultaneously. There is no clear answer here as to how to resolve this, and the consumer of IP location data should be aware that there is not necessarily a tight correlation between a single individual user (as a single physical location) and a single IP address, and this will necessarily add some variability to the resultant location information for some IP addresses. For example, in a mobile context, the radius of uncertainty of a location given in latitude/longitude coordinates may be many hundreds of kilometres because the address may be observed to be in use across all of these potential areas. On the other hand, too precise a location can become personally identifying information and potentially cause harm to users.

In MaxMind’s case, they limit the precision of a radius of uncertainty to no smaller than 5km, as there are concerns related to the protection of individual privacy where a more precise location information is used in this context.

However, the role of geofeed data is important in this area of associating an IP address with a location, and some sites provide some insights as to who uses this geofeed data. Geo Locate Much is a very good example of which location providers make use of this geofeed data.

Many of the consumers of this data are motivated by a desire to comply with location-based constraints, such as DRM, where a provider has purchased the right to retail content or service to a particular geographic territory. There is also a related issue of legal compliance, and there are issues of compliance with government-imposed sanctions, and the levying of taxes and tariffs on the provision of digital goods and services that may apply depending on the geolocation of the provider and consumer. For many of the users of this data, there is a strong interest both in access to data that reflects an up-to-the-second view of a user’s location and a strong interest in highly specific locations.

There is a second community who use location as a demographic attribute to profile users. A good example is the ad placement industry, where an advertiser may want to purchase the placement of online ads that are directed to particular locations, in addition to other demographic profile specifications. The value of this data to the ad placement operator is generally lower than the value associated with legal compliance.

A further class of consumers are related to the cybersecurity activity, where the analysis of threats and the associated calculation of risk uses location as part of the inputs to such assessments.

There is also the role of using location to meet users’ expectations for content, context and experience customization. A user who is geolocated to Germany, for example, might expect that by default the language of presentation used by the browser would be German. Geolocation can also assist in choosing a nearby server to service a user’s request, on the assumption that closer services will provide a superior user experience. There are also the expectations that search results use a context of locally relevant material in preference to other material.

Some of the anomalies that can arise come from the misuse of geo data. A service provider may have purchased a geofeed with the primary objective of optimizing the user experience when accessing their service, but apply the same geo data for the application of controls to comply with regulatory constraints. For this secondary objective the geo data may not be sufficiently precise, nor timely.

A perspective from a Content Distribution Network (CDN) operator — Akamai

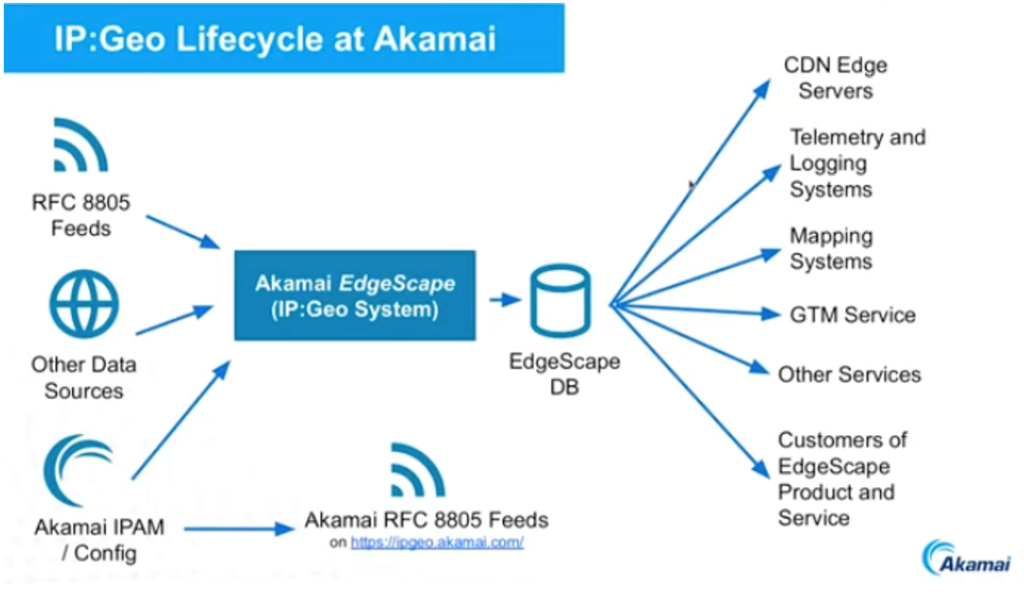

Akamai sell a product called Edgescape, which is a collection of IP geolocation feeds, using the RFC 8805 format. Like other IP geolocation providers, Akamai take a variety of IP-to-location sources and creates a single outcome based on the confidence scoring of the various inputs. They also use the same data for their internal use, such as selecting a service to optimize the responsiveness of service requests. (Figure 1).

What Akamai produces is a deliberately coarse approximation of the location of a publicly routable IP endpoint, whether it’s a client device, a DNS resolver, a data centre server, or a Network Address Translation (NAT) exit point of a geolocation sentinel.

As a cloud content provider, they use a location-informed DNS server to direct a user to a nearby (in network terms) content server. The distinction here between this form of IP geolocation and that generated by MaxMind is that it’s the network gateway that’s important to Akamai, and not necessarily the location of the user. Thus, for VPN users, it’s the VPN egress point that is identified by Akamai’s geolocation service. For geolocation-informed DNS, they need to perform IP location at high volume and low delay.

The geofeeds published by networks are valuable in assembling this data, but they are not necessarily sufficient. Many network operators do not self-publish a geofeed data set. Those that are published are not always accessible, and there is an unknown delay between the time of gathering the information used to inform the geofeed data and the publication of the feed itself. They also observe some level of discrepancy between IPv4 and IPv6 location data, where the use of the same endpoint identity token shows that this is the same endpoint device, yet the geofeed IPv4 and IPv6 data show divergence in the described locations.

A related issue is IP ‘reputation’, which is similar in many ways and different in some important ways. IP reputation has a very important time axis, where compromised endpoints have a rapid impact on the associated reputation score, while location changes at a far slower rate, if at all.

The RFC 8805 format does not contain a time, geolocation precision or confidence of the data contained in the data. It would also be useful to classify the address by network type, such as data centre or cloud infrastructure, mobile network, fixed access, or enterprise.

Prefix length is also an important consideration. Currently, there is no easy way for content providers to know the end-site prefix size of a party accessing their service. Knowing this end-site’s prefix size has multiple implications, such as blocking or throttling, rate limiting and location.

The use by location-informed DNS is interesting, as in this case, geolocation is an instance of a third-party triangulation problem of relative location: How can an observer (the DNS server) determine the ‘best’ server for a given user when the observer is neither the user nor the server? There are also compliance aspects to this triangulation problem, as the selected server choice may be constrained by regulatory considerations as well.

Geolocation is a convenient shorthand for a set of quite different questions. Using a hypothetical ambulance dispatch scenario, these include where the patient is located (the user’s location), which ambulance station should respond (a server or service location decision), and what equipment the dispatched ambulance should carry (a user-experience or service-optimization issue). There is also a more fundamental question — whether an ambulance is needed at all, or a fire truck instead. The most problematic outcomes arise when one type of geolocation question is asked, but the answer provided relates to an entirely different one.

A perspective from a content intermediary — Cloudflare

Cloudflare’s role in web-based content and service delivery can be considered as an active intermediary between the user and the web service that they wish to access. The behaviour of Cloudflare’s intervention is determined by the web provider for the service, and not necessarily by Cloudflare. Cloudflare provides control mechanisms to web service providers, but how a web service provider sets these mechanisms is up to them. Cloudflare’s service could be described as a ‘content conduit’.

Cloudflare is also an access provider with various VPN-related access products, predominantly for enterprise markets. Cloudflare consumes IP geolocation products provided by others and uses this to map users and services to locations, but in this case, Cloudflare is neither the user nor the service provider.

Cloudflare operates CDN services in 330 cities in 125 economies and makes extensive use of anycast to assist in steering users to the closest service, where ‘close’ is defined in network terms. This also implies that all infrastructure addresses used in Cloudflare’s anycast CDN service have no single location, and this does not necessarily fit in a conventional model of IP geolocation that wants to associate an IP address prefix with a single location or single jurisdiction.

The gaps in geolocation that Cloudflare are aware of include:

- A lack of recorded provenance of the location mapping data.

- A lack of timing between data updates and pickup by various location data brokers.

- A lack of transparency in the data broker decisions between potentially competing location claims.

- A lack of a framework to describe data quality and a clear way of measuring it.

If the ultimate objective is to map a human user to a physical location then the use of geolocation of IP addresses is a convenient and potentially low cost shortcut to achieve this, but it has some fundamental weaknesses when you consider operational practices of dynamic address assignment, address sharing through NATs, the use of active proxies as intermediaries, variable quality of location, opacity of operators’ address plans and so forth. The technique of using IP addresses to determine geolocation is cheap, fast, and efficient, but has some rough edges relating to determining the quality of the result.

IP addresses are not the only location proxy, and other signals are feasible in certain contexts. Web location, as provided in the HTML Geolocation API, can be accessed, with the user’s permission, or the mobile device location available at the application level is used.

This location technique uses the device’s GPS or mobile/ Wi-Fi signals to detect location and operates with high precision down to the level of a small number of metres of uncertainty. It requires the explicit permission of the user through a browser query or configuration session. Used when the exact location of a user is required, for example, locating a user on a map to find travel distances to a destination, or delivery of services to a residence. The high level of precision has privacy issues, and there are no explicit limitations on what the service provider can do with the data obtained in this manner, as presumably the service provider now knows the device IP address as well as its location to a high precision and could sell this collected data to others.

The IP address by itself is a poor proxy for a user’s location. On the one hand, if an IP address can be mapped to a location and purpose with some level of surety, then it’s possible to build a reputation for that address, including a profile of a ‘normal’ pattern of network use. The address might be used by a residential access service in a fixed location, shared across residential users in a bounded locale, or used in a mobile access network, with associated broader parameters of the bounds of a locale of use. The address might be a VPN or tunnel interface, in which case the IP address is opaque as to the location of the user at the other end of the tunnel. The address might be used for network or service infrastructure, in which case it would not normally be used to initiate outbound connections. This form of additional metadata about IP addresses could assist in the detection and response to unwanted or hostile traffic by network and service operators.

On the other hand, there is an obvious tension between user privacy and the potential to exploit location metadata to harden networks to actively resist various forms of hostile attack. Location establishment processes, authenticity of the data, and an understanding of the meaning and context of the data vary widely between data publishers, data processors and brokers and users. It would be far easier to support users who are impacted by location attribution errors if we knew who to talk to, how to submit corrections, and how to make available the provenance and confidence in the data.

The result we have today with IP geolocation is highly chaotic and places probably too much reliance on inference and guesswork.

The perspective of an RIR — the RIPE NCC

A different aspect of geolocation is establishing the location of network infrastructure, as distinct from the location of the network’s users.

One motivating question is an effort to relate a natural event at a given location to assess the likely impact on network infrastructure. Another motivation is to expose the geographic path taken by Internet packets when using traceroute, such as GeoTraceroute. This can expose potential performance-related behaviours such as hair-pinning, when traffic passed between geographically adjacent points is passed through a remote waypoint.

There are also network path questions that are of national interest. Is traffic to/from some remote service point passed across network infrastructure located in a particular economy or economies? Or does traffic between two endpoints within one economy pass through other economies? Or is critical infrastructure for my economy’s users, such as authoritative DNS servers, for example, located in other economies? And there is the more general question of assessing the extent of Internet self-resilience for an economy. To what extent are domestic Internet services reliant on services located in, and controlled by, foreign entities? All these questions necessarily involve establishing the geopolitical location of network infrastructure.

The RIPE NCC have commenced an initial service to maintain a public data set that contains the geolocation information for internet infrastructure, located by an infrastructure element’s IP address. The sources they use include the IP address databases maintained by the RIRs, which serve as a broad hint but have little use in terms of precision.

There is the PeeringDB data set, which has reasonable accuracy but limited coverage. There are also geofeeds, and it is also possible to mine the DNS names of infrastructure elements and then make some inferences based on the labels used in the DNS name (such as the thealpph.ai project at Northwestern University in the US). There is the option to use crowdsourcing or use association hints from previously positioned IP addresses to infer the location of the covering address prefix. There is also basic triangulation, where a low delay between path-adjacent IP addresses can infer some level of geographic proximity. These various location hints can be assessed with a level of confidence. This tool is under current development at the RIPE NCC.

It’s an activity not without aspects of controversy. Infrastructure maps (such as Open Infrastructure Map) necessarily need to walk a careful line between providing public information and overexposing critical infrastructure to the potential for hostile disruption, and as we’ve seen in the submarine cable world in recent years, deliberate disruption of communication systems can have extremely far-reaching consequences.

Location and regulatory compliance — GeoComply

One entity has based its business model on the observation that IP geolocation is not a good fit for various overlay business models that demand high precision. For example, in sports betting in the US, some states have compliance constraints based on tribal land boundaries, and this requires a level of positional precision beyond what is normally available in GeoIP. Use of VPNs effectively ‘teleports’ users and can be used to bypass territorial business models.

The content industry has used regional pricing models for many years (for example, Amazon Prime Video is six times more expensive in the US than in India, and YouTube Premium is close to four times more expensive in Switzerland than Serbia), and VPNs can undermine such differential business models by teleporting a user to a region where the same service is cheaper to access.

VPN use in the retail access space is widespread, with some 1.75B users (one third of the total user base) regularly using VPNs for reasons that include privacy, security, bypassing local censorship actions and access to geo-restricted content. The global VPN market is currently valued at some USD 44.6B, with projections for continued strong growth in the coming years.

Given the deliberate manipulation of the visible IP address to use that of the VPN egress point, and not that of the device, then if the objective of GeoIP is to locate the user, then this does not work! Many parts of the industry have turned to application-based location sharing, where the platform gathers the user’s consent to share the device’s geolocation with the application service provider. But can an application service provider trust this location data even if the user has provided explicit consent? Not really. As much as there are apps can tap into a device’s location, there are also apps that rewrite a device’s location to deliberately mislead these location-aware apps! The download statistics for GPS spoofing apps number in the 10s of millions and rising!

There is an asymmetry of relative value in location determination. It may well be that the privacy of my location is important to me and I might be prepared to spend some money to ensure its privacy or obscure any location I may provide from my device, but to some providers, I am just one consumer out of millions and the value of knowledge of my location to the provider is not as valuable as it is to me to conceal or obfuscate this information. In many scenarios, a provider is not prepared to spend the same amount to find out my location as I might be prepared to spend to obscure it, should I choose to do so. This picture changes to some extent when regulatory imposts may also entail large fines for breaches, increasing the motivation of the provider, but as an economic issue, it’s generally the case that my location is far more valuable to me than it may be to any third party.

The effort to establish the true location of a device necessarily needs to pull in more data from the device, including the local time of day, the nearby Wi-Fi SSID names and their signal strengths, in addition to the IP location and the reported GPS coordinates, if the device is GPS-capable and receiving a signal.

Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) can also work in favour of geolocation, where the application requires the use of a mobile device to authenticate the access attempt and thereby also provide the device’s GPS coordinates as part of the authentication process. To an extent, this relies on user consent and testing whether the device is deliberately obfuscating its location. On the other hand, in terms of identifying and countering various forms of fraud and deception, establishing a user’s usual pattern of locations allows non-local access attempts to the readily identified and flagged, adding a further measure of protection for the user.

The perspective of a satellite operator — Starlink

Starlink is creating a significant impact on the Internet. Starlink is a service that is based on a Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite system, and the proximity of the spacecraft to the earth-based user means that it’s possible to provide a high-speed low low-latency service that is competitive with existing terrestrial-based Internet access networks. It has a further feature that allows spacecraft to relay IP packets between each other at high speed (100G), which allows a user to be arbitrarily distant from the ground station that they are using. Starlink services are accessible across the entire surface of the Earth, including ships at sea in international waters, and aircraft in flight.

From Starlink’s perspective, they want to route their users to a ground station that is the lowest latency point that can provide region-appropriate content. From a Starlink user’s perspective, there is the expectation that the experience as a Starlink user should be equivalent to the experience of a user in a similar location using a terrestrial access service.

The question changes somewhat when the user is in international waters or in extraterritorial space such as the polar ice caps (for as long as they still exist). Where should a geolocation service ‘map’ users at such locations? The question of location also has implications for mobility. With Starlink, an aircraft in flight will retain the same public IP addresses for the duration of the flight, even though the takeoff and landing points may be half a world apart. The compromise Starlink has adopted is to select a fixed location mapping in terms of reported geolocation economy and region, even if the user (or aircraft) is roaming.

As with tunnels and relay-based networks, the user’s location and the locations where the Starlink network connects to the public Internet — its Points of Presence (PoPs) — are not necessarily the same. For example, many Starlink users in France are served via PoPs located in Germany, Italy, or the UK. This raises the question of whether such distinctions should be reflected in geofeed data.

It appears technically feasible to extend the geofeed specification to include both PoP location and user location. The data could also indicate whether an endpoint is roaming, although that would introduce a time-dependent element that sits well outside the current scope of geofeed data.

Starlink’s preferred approach is to optimize traffic based on network topology rather than physical geography, and to embed user location signals within the application environment instead of relying on location inferred from IP addresses. A good example of this abstraction higher up the protocol stack is the use of location metadata in DNS queries, such as Explicit Client Subnet (ECS).

In spite of this desire to shift away from an IP address location signal, Starlink publish a geofeed that maps IP addresses to economies, regions and cities. It is not the location of the ground station PoPs that interface to the Internet, and not necessarily the location of the Starlink terminal equipment, as evidenced by Starlink Roaming services. It appears that, on the whole, the Starlink geofeed locates the user to the location provided to Starlink when they executed a service contract with Starlink. An administrative location seems to be an appropriate description of this particular geofeed published by Starlink.

There are more LEO-based satellite services coming. It would be a preferred outcome if these LEO satellite constellation operators could work with the standards folk to devise a common reference model to describe location and a common reporting framework for location mapping.

Starlink services to aircraft reopen the topic of the location of aircraft in flight. In terms of legal jurisdiction, the Tokyo Convention says that the people on the aircraft are subject to the laws of the economy of the aircraft’s registration when the aircraft is in flight on an international route. Should the IP addresses obtained by the aircraft’s on-board Wi-Fi service reflect this? What happens when an airline runs a service between two ports that are in the same economy, but not that of the airline, such as a Qantas flight operated between Los Angeles and New York? Is the answer the same if the aircraft on such a flight overflies international waters or other economies? If the answer indicates that a change in the jurisdictional compliance location is appropriate, are geofeed systems capable of reacting to this update in the notional location of an aircraft’s passengers in anything like real time? Current systems have a lag that is measured in days, not minutes. Even a moving event, such as the IETF meetings, has issues in this space when the event moves locations just three times a year.

Reflections — CDNs and IP geolocation

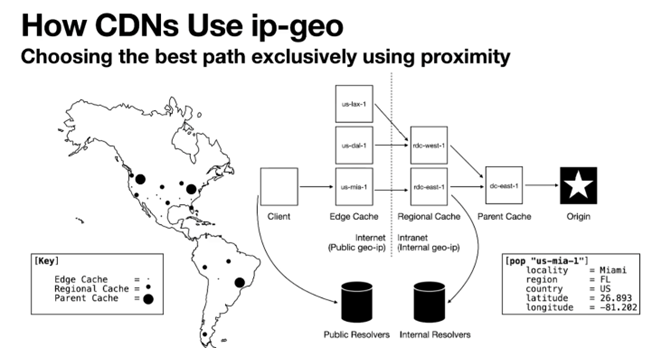

One of the goals of geolocation for CDNs is to associate the user with the optimal selection of an edge cache, so that the content can be delivered reliably and at the desired speed.

Much of the task can be passed to the DNS, where the CDN assumes that the user and the DNS recursive resolver that handles the user’s queries are co-located to some acceptable level of proximity, and the processing of a DNS request relating to a service name that is served by a CDN platform is based on a triangulation of returning the IP address of the cache server that is considered to be closest to the client’s DNS resolver (where ‘close’ is a network based distance as distinct from a geographic distance).

When a CDN is attempting to select what is optimal for the user, there are considerations of client/server latency and network path capacity, and potential backup selections to be used when the session is disrupted. There is also what is termed ‘hyperlocal’ data, such as local weather content. There are also considerations of copyright and licensing, and geo-blocking that can remove some candidate server selections. For many CDNs, it is feasible to maintain a ‘proximity and performance’ map, as distinct from a geographic map and make server selections based on recently recorded performance data, as well as the proximity of the end user to the candidate edge caches. This map also has an internal counterpart, where these edge caches are fed by regional caches and back to parent caches and the original origin source or sources (Figure 3).

It’s also possible to use a ‘connection race’ where a service request triggers multiple servers (and potentially uses both IPv4 and IPv6) to send the initial transport handshake connection, have the client select the first response it received, and reset all the other attempts. For long-held content sessions, it’s also possible to ‘dither’ the local cache selection and periodically have alternate local caches send content chunks, and if the performance of the alternate cache server is superior, then the session can shift over to the other cache server.

An alternative approach is to include more information in DNS responses, allowing clients to make their own decisions about which server is optimal. A similar idea can be applied at the HTTP layer, where a client can convey its network geolocation to an HTTP server using an HTTP header field.

This approach allows geolocation accuracy to be set by the client and gives users greater transparency over who receives their location information. It is particularly useful where NATs, relays, or VPN tunnels are in use, as these mechanisms undermine IP-address-based geolocation, provided the client is willing to disclose its location to the server.

An alternative is possible with Obfuscated HTTP (OHTTP). In this model, the OHTTP relay is aware of the client’s IP address, performs a geolocation lookup on that address, and forwards only the resulting GeoIP record — not the IP address itself — to the OHTTP gateway. This approach is described in the geohints draft.

There are multiple types of such IP teleportation proxies. Some VPNs offer a large set of egress choices on an economy-by-economy basis as the core of their business differential value. The aim of such VPN services is not to provide an accurate GeoIP location, but to do just enough to meet the distant location’s compliance criteria to allow the VPN client to access content that was otherwise not permitted in their physical location.

On the other hand, simply obscuring location and other aspects of the user’s profile is a challenging topic. Google has recently (October 2025) shut down its Privacy Sandbox initiative, which was launched in 2019 to develop privacy-protecting technologies for online advertising as an alternative to third-party cookies. The project aimed to balance user privacy with the needs of the ad industry, but its technologies, including the Attribution Reporting API, Protected Audience, and Topics API, are now being retired.

Given the huge market share of Google’s Chrome browser, efforts by Google to make it extremely easy for users to limit the extent of data generation that allows others to profile users, including location of course, naturally attract the attention of governments and other service providers, and the outcomes of such scrutiny are at best highly unpredictable! The compromise Google came up with was to develop a web-based mechanism that still has aspects of location reporting, but at a level where the granularity was intentionally at some half a million users or so.

IP geofeeds

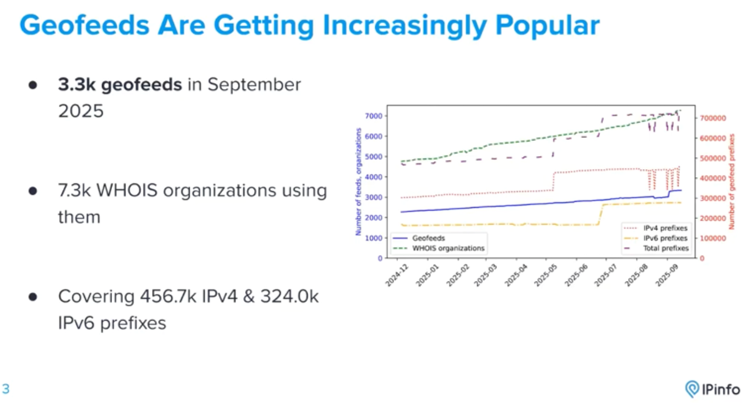

Geofeeds are an important part of the ecosystem for IP geolocation and continue to grow in levels of adoption (Figure 4).

Geofeeds are one of the few mechanisms available to network operators for publishing location information in an interoperable, machine-readable form. They are far from perfect, as the weaknesses outlined above show. However, it is unclear whether there is sufficient shared incentive to invest in building and maintaining a richer geofeed dataset, or how network operators could monetize such an effort.

Despite these limitations, geofeeds are widely used. There is currently no comparably priced alternative, so in practice, the community tolerates their shortcomings because there is little else available.

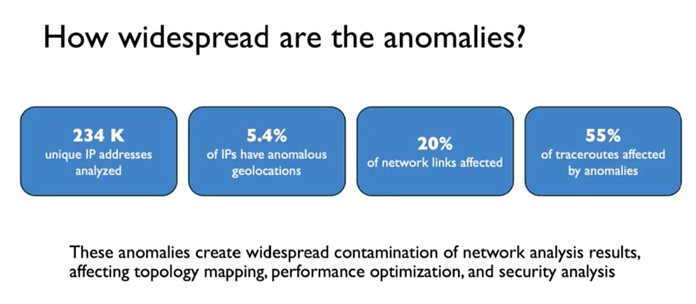

Research work comparing traceroute data with geofeed data sets at the University of California, Irvine, certainly indicated the relatively poor quality of the data, where some 5% of IP addresses have anomalous location information, and this appears to lie in infrastructure addresses, as 55% of traceroutes include these anomalies (Figure 5). Experimental techniques can resolve many of these anomalies, but the question remains whether the effort required to perform this anomaly resolution results in a tangible increase in the value of the aggregated geofeed data.

Applying traceroute times to geolocation questions has some weaknesses. Traceroute cannot report one-way delay, so it only reports the Round-Trip Time (RTT) from the sender to the reporting point and back. If the return path varies for the intermediate points on the forward path, then traceroute itself reports anomalies that are challenging to analyse. In the exercise, the researchers use Paris traceroute and multiple traceroutes from multiple points to try and address any such traceroute anomalies, but it’s unclear how effective this is.

What are the issues here in terms of trust and accountability? Geofeeds are a collection of self-assertions by a collection of entities that are not directly accountable to any particular public function or authority. It seems somewhat anomalous to see various forms of government regulation and even legislation that relies on a foundation of trustworthy and authoritative data that assumes the existence of a working framework can reliably locate users and the devices they are using in an economy, state, or even local authority, when in fact that foundation is fundamentally fractured! However, governments, as well as the industry’s content distribution system today, have locked in an assumption that geolocation is available and is working acceptably well. Imperfect as it may be, it’s something we really must accommodate.

Geofeeds are certainly convenient, but do not withstand critical scrutiny in terms of being fit for purpose. The issues with geofeeds include:

- They have an implied precision, but should that be explicitly described?

- They use civil names for higher precision locations, but do not provide a reference set of descriptors for such civil names, nor a character set to use.

- They have no alternative location descriptors, such as latitude / longitude coordinates.

- They cannot add attributes to the IP address prefix to designate unicast vs anycast and shared NAT use vs dedicated use vs infrastructure use.

- Mobility is an unaddressed issue.

- They do not describe the source of the geofeed data — they rely on the location of the feed from where it was retrieved to provide an implicit signal of authenticity

- They do not include times relating to use (as the DNS TTL).

- They contain no implicit signal of user awareness and consent. There are many nuances for consent. How can a geofeed convey such nuances?

- They have no way to describe confidence or authenticity in the accuracy of the data

- There is no mechanism provided for the distribution of this data. How to discover a geofeed, and how to assess the confidence in the authenticity of a geofeed?

- How are errors noted in a geofeed, and who is the relevant contact point for amendments to a geofeed?

- Who maintains geofeed data elements? How frequently? Under what authority?

It’s definitely not ideal for the parties that have an interest in location data. A lot of the time it’s so far from ideal that it cannot be trusted for all but the coarsest of positioning tasks. But the industry has managed to adapt to what it does today, adapting to both its weaknesses and defining what role it plays in today’s environment. You’d probably go hungry if you relied on IP geolocation to get a pizza delivered to your door! On the other hand, you would be likely to stream economy-limited content to your device or get a reasonably relevant weather forecast from your residential connection.

Are IP addresses the ‘right’ tool for location?

Perhaps these issues are fundamental to the approach of using IP addresses as a proxy for geolocation. Semantically, IP addresses were originally intended to convey the identity of an attached endpoint and the network-relative location of this endpoint. The intended outcome was to be able to pass a packet into a hop-by-hop stateless forwarding framework and have the packet reach the intended destination. The intended destination was identified by its interface IP address (identity), and the sequence of network forwarding decisions to pass the packet through the network was informed only by this destination address (network location).

However, network location is not necessarily physical location. IP addresses are not distributed according to a geographic hierarchy, and they have no geographic significance. IP addresses are distributed in a manner aligned with individual network providers. It is a happy coincidence that most network providers operate within a national jurisdiction, so the IP addresses they deploy to meet their customers’ needs align with the economy in which they operate.

So, to a first-order approximation with many exceptions, IP addresses can be aligned to individual economies. This alignment can be seen in the reports generated by the address distribution agencies, the RIRs, in their data reports. It must be stressed that the geolocation was not a motivation behind these reports. The CC in these reports reflects the location of the head office of the enterprise that received this address allocation, not the location where these addresses are used on the Internet.

These address-holding entities may have operations in many economies where they deploy these addresses. This data is not necessarily reported to the RIRs, and the RIRs do not generally publish this data. The end user may use VPNs, relays, proxies or other forms of encapsulation or obfuscation to deliberately shift their apparent location elsewhere or conceal their local IP address completely. Several reasons, including address scarcity and anycast services, caused many service providers to deploy address-sharing technologies that deliberately break any unique association of an end device and the IP address that can be used to direct packets to it.

If an IP address can be used by many devices in many locations, then the objective to associate a physical location with each IP address is fundamentally undermined. The issue here is that an IP address does not self-identify its context of use. While we continue to use IP addresses in a manner that is still consistent with the original view of being a token with identity and network location properties, the cracks in this approach are clearly evident.

Alternatives to IP geofeed data

If not IP addresses, then what else is there?

There are many ways to identify a location. These include latitude and longitude coordinates, and related systems such as geohashes. Location can also be described using economy names, regions within an economy, or cities. At a finer level of detail, postal addresses combine these civil identifiers to pinpoint residences or workplaces.

There are means of discovery of location, including the use of global navigation systems (GPS, Galileo, GLONASS and BeiDou) to perform self-discovery of location. There is associative location discovery using Wi-Fi SSIDs or mobile cell tower identifiers. And there is the recycling of the surveying practice of triangulation using digital triangulation with accurate timing and reference locations. All of these have attributes of cost of operation, precision, accessibility, spoofability and deniability.

An IP location is not useful for a pizza delivery business. But it is tolerably useful for compliance with national regulatory constraints, and the exceptions in economy-level locations are adequately offset by the high availability of this data, low cost of access, and permissionless use.

If we wanted to use a different location signal, then the attributes we would be looking for would include high reliability (not necessarily high accuracy, but reliable in terms of its intended accuracy), high trust (including resistance to spoofing by the end user or by third parties), high availability, and low cost. It would also be good if we could find an acceptable compromise between privacy and accessibility that avoids both consent exhaustion and data theft.

One possible approach borrows from the Web PKI (where a selection of trusted CAs verifies that a party has control of a domain name), where a selection of trusted location verifiers verifies the location of a user’s device and issues a certificate to that effect, which can be loaded by the user’s device. The user application can then present its location certificate and some proof of possession of the device’s private key used in the location certificate request to attest its location to a server.

The invocation of keys and certificates may give the appearance of invulnerability to subterfuge or spoofing, but that is a misleading appearance. The certificate issued by a location verifier attests that it applied some checks on certain data and represents that the tests indicated that the device was at a certain location at a certain time. Nothing is stopping the device from being physically moved to an entirely different location following location verification. Or allowing the device to export both its location keys and location certificate to a different location.

Perhaps there is more here despite the overt issues with certificate and key management. This approach changes the concept of how location is conveyed to an interested provider. Instead of having a third party generate its own map of where it believes that devices are located by recording the IP address used by each device and the associated device location, have the other party to a transaction directly interrogate the client device as to its location, and request that the client device furnish its location and some credentials to allow this assertion of location to be verified (to some extent).

The RFC 8805 IP geofeed location coordinates using cities are deeply unsatisfactory in terms of the variability in precision and personally identifying information. For example, a geofeed entry for ‘AU,AU-NSW,Wombat‘ places you in a pool of just 225 individuals, while ‘AU,AU-NSW,Sydney‘ identifies a pool of 5.6M individuals.

The concept of a geohash has had some traction as a potential alternative. A geohash encodes latitude and longitude coordinates into an alphanumeric string. It is a hierarchical, grid-based system where the length of the string determines the precision, with longer strings representing smaller, more precise areas.

Geohashes are useful for spatial indexing, as they convert latitude and longitude coordinates into a single value that supports faster and more efficient proximity searches. The choice of precision is context-dependent. For example, I might provide a pizza delivery service with a geohash precise enough to identify my residence, while deliberately using a much coarser geohash — perhaps only at the city level — when sharing location information with a CDN.

The weakness of the geohash system is that it does not align with geopolitical boundaries, so its use in contexts of compliance is limited unless you select a high-precision geohash. If you make the grid size of the geohash framework large enough to encompass the entire economy, in many cases, it’s likely that the geohash cell will include not just the intended economy, but adjacent economies as well.

The next likely steps include an effort to develop some standards relating to latency-based server selection, adding SVCB parameters relating to network location into DNS responses, and standardizing IP geolocation HTTP client hints. These steps work to a common objective of putting the end client back to the loop about the disclosure and use of geolocation, which is a substantially different picture from today’s framework, which is largely driven by network and service operators without any engagement by (or even informing) clients of any location tracking that is taking place.

What do we want from a location framework? That’s a harder question, and I suspect that answers vary depending on who you ask and what your use case might be.

- Accuracy. When I am using a location tracker to find my misplaced keys, then accuracy to a metre or so is really helpful. On the other hand, if a social network platform wants to display my current location, then I might find an accuracy of a few tens of kilometres to be an uncomfortable intrusion on my expectations of personal privacy.

- Privacy. To what extent can I control the dissemination of my current location? Or my location history? Can third parties derive my location without my consent and then on-sell this information to others? This appears to be what happens with advertising platforms that might purchase a location service and use this information to guide advertisement placements. Privacy is not an absolute attribute. It is probably more useful to think of this as the level of correlation between expectations and reality.

- Public or private? Is my location part of some public domain of data? Is my location personal and private?

- Control. Can I control the accuracy of my reported location and who may access this data? Can I deliberately misrepresent my location? Is my location part of a portfolio of personal information that should remain under my control at all times?

- Authority. Who is asserting that this is my location? Under what authority are they making this assertion?

- Verifiability. Is my reported location ‘true’? Are the physical coordinates, with the bounds of accuracy, true? Is this really me?

- Consistency. Is this the location of me, my device, my residence, or my workplace? Is this a physical location, a geopolitical location, or a location relative to network infrastructure? How current is this reported location?

- Scalability. Is this framework one that can encompass billions of users and potentially hundreds of billions of devices?

- Politics and law. Are the locations of all the people who are in an economy part of a portfolio of national critical data? Should such data be accessible, or even derivable, by foreign entities, public or private? Are there distinctions that should be made with respect to an economy’s citizens and so-called aliens? Is my location data protected under the law? What constitutes ‘unauthorized use’ of my location data?

While it’s routinely broken in many ways, a common understanding of what can be improved and who is willing to invest the effort in defining, seeding, and maintaining an improved location infrastructure is clearly not evident so far. It seems that each party sees a different ‘solution path’ that would address its needs, and there is not a lot of evidence that these differing objectives can be coalesced into a single path.

The next big steps appear to point to application-based location — the problem is that each application does not have the momentum or value to sustain a framework custom geolocation solution per application, and the application environment is fragmented to the extent that a common application-level framework is left to the Android and Apple platforms. We see 2FA has moved into that space already, and the rest are following — that location is transactional outcome, not a constant attribute.

Moving to gathering a user’s location as a transaction at the application level does allow a more explicit form of user consent. It seems reasonable to require applications to have clear privacy policies explaining data collection and sharing, and require explicit user consent (opt-in/opt-out) to sell or share location data, especially for advertising or analytics. For an app to access the device platform’s location, the developer needs to justify its use, and users can manage these permissions in settings.

However, theory and practice often head down divergent paths. Researchers from the International Computer Science Institute found up to 1,325 Android apps that were gathering data from devices even after people explicitly denied them permission.

Serge Egelman, Director of Usable Security and Privacy Research at the International Computer Science Institute (ICSI), presented the study in late June at the US Federal Trade Commission’s PrivacyCon. He argued that consumers have very limited tools or signals to help them meaningfully control their privacy or make informed decisions. As he noted, if app developers can simply bypass these mechanisms, then asking users for permission becomes largely meaningless (as reported by CNET).

Reflections on privacy and location

Most people would agree that an individual’s precise location constitutes personal data and falls squarely within the realm of personal privacy. From there, several broad positions can be taken. One view is that, in today’s digital environment, personal privacy is largely a historical concept and individuals should simply accept its erosion. Another is the more permissive approach often associated with the US, where the use of personal data is generally considered acceptable provided its potential uses are disclosed in advance. In contrast, the European Union’s approach, embodied in the GDPR, grants individuals strong rights over their personal data and places clear limits on how it may be collected, processed, and used.

Today, the use of personal location data spans a broad spectrum. It is employed for advertising and user experience customization, such as tailoring service language, local time settings, and targeted content. Location data also supports security, helping detect anomalous activity associated with an individual’s identity. Additionally, it underpins compliance, as content and service providers are often legally required to restrict access based on a user’s location within specific jurisdictions.

User consent is a core principle of data protection and privacy. Use of metadata obtained from network infrastructure using IP addresses to map the user-side endpoint of a transaction to a location could be seen as an abuse of an individual user’s privacy, particularly when this harvesting and analysis of this data occurs without users’ knowledge or explicit informed consent.

Government actions in this area are often inconsistent. Many jurisdictions regulate access to certain types of content and services, limiting their enforceability to within their borders. As a result, service providers seeking compliance must collect user location data to determine which restrictions apply. At the same time, in many regions, collecting or using personally identifiable information without informed consent violates privacy laws, potentially exposing service providers to legal risk.

The use of IP addresses for geolocation falls into a very grey zone in this respect. An IP address that is statically and exclusively assigned to a residence may well be considered a personally identifying data point and should be treated as such. A public IP address that is used by a large-scale NAT and is shared across hundreds of thousands of users has almost no residual capability to identify any individual user. Can you tell the difference between these two forms of IP address use when looking at the IP addresses used in an individual transaction? Obviously not.

What are users’ expectations regarding privacy? In general, most free and democratic societies seek to protect a biographical core of personal information that individuals wish to maintain and control from dissemination to the state. The biographical core is not limited to identity, but includes information that tends to reveal intimate details of the lifestyle and personal choices of the individual. There is a recent (March 2024) Judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada on this topic, which is well worth reading.

It’s not just public authorities. Business obligations can be at odds with informed consent as well. Content licensing agreements require coercion of users to have their location revealed, and the business arrangements are not viable otherwise. The outcome is that the logic of business interests apparently overrides the interests of individuals when infringing on their expectations of privacy, and it leaves the individual user with minimal privacy protections under the law, if any.

This line of reasoning can lead to a conclusion that locating a user should be handled at the level of the use of individual applications, and informed consent should be obtained by the application. There are cases where this is already done, such as the controls for Location Services in the iPhone environment and the W3C Geolocation API. (Even so, the risks of ‘consent exhaustion’ should be factored in, where the constant stream of popups demanding a renewal of consent to use location information does little more than motivate users to simply click through to resume what they were trying to achieve in the first place.) The current status quo of the unconstrained dissemination of geofeed data that allows any party to map IP addresses to location without the context of the user being informed of this activity, let alone the user’s consent, should be, at a very minimum, discouraged. We don’t even have a common understanding of what is tolerable as a compromise between geographical precision and respect for personal privacy.

This line of reasoning suggests that user location should ideally be managed at the application level, with informed consent obtained directly by each app. Examples of this approach include Location Services on iOS and the W3C Geolocation API. Even so, the risk of ‘consent fatigue’ remains, where repeated prompts for location access can lead users to click through without meaningful consideration. By contrast, the current unconstrained dissemination of geofeed data, allowing parties to map IP addresses to locations without informing or obtaining consent from users, should, at a minimum, be discouraged. There is still no common understanding of what constitutes an acceptable balance between geographical precision and the protection of personal privacy.

It may well be that IP addresses are simply the wrong starting place to fulfil these desires relating to compliance, security, customization and performance: ‘You cannot get to where you want to go from where you appear to be!’

Conclusion: Time to replace IP geolocation

IP geolocation is an outdated technology that creates conflicts between utility, legal necessity, and user privacy. Better solutions are feasible, but the community needs to implement and standardize. Moving away from IP geolocation benefits user privacy, web services and network operators.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.