IPv6 scanning has often been compared to finding needles in an impossibly large haystack. With an address space of 2128, blindly sweeping the entire IPv6 Internet is practically infeasible. Instead, IPv6 scanners must cleverly choose their targets using hints like active address lists, Domain Name System (DNS) records, or routing announcements. For network defenders and researchers, this raises a challenge: How do we observe and analyse IPv6 scanning when malicious actors could be probing only selective, obscure corners of the address space?

Our work at CoNEXT 2025 rises to this challenge by deploying the largest-ever IPv6 ‘network telescope’ and capturing the largest IPv6 scan traffic dataset to date. The findings paint a striking picture: IPv6 scanning activity has skyrocketed by one hundred times in recent years, and diversified across many more sources.

Equally important, the research shows that traditional passive monitoring isn’t enough. Only by proactively advertising decoy IPv6 targets — via Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) routes, DNS names, Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificates, and so on — can we lure out the full spectrum of IPv6 scanners. This blog post summarizes the key insights for network operators and security professionals, and what they mean for the future of IPv6 network defence.

IPv6 scanning on the rise — and coming from all sides

One of the motivations for this work was an alarming trend: IPv6 scanning activity has been steadily growing year over year. By analysing two years of background traffic to an Internet content provider, we observed a one hundred times increase in weekly IPv6 scan packet volume from early 2022 to late 2023.

At the start of 2022, a couple of extremely active scanners dominated the traffic, but by the end of 2023, the traffic came from a broad range of sources. The number of distinct scanners, scanning by source IPv6 addresses, /48 subnets, and Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs), grew steadily throughout the period. This dispels any notion that the huge address space of IPv6 has deterred attackers. On the contrary, malicious and research scanners are finding ways to navigate the IPv6 Internet’s vastness, and their ranks are growing.

Why is IPv6 scanning rising now? Likely because attackers have developed more intelligent methods to discover active IPv6 targets, and a critical mass of IPv6 deployment means more to scan. Notably, the study found that quiet IPv6 networks (with no advertised services) tend to attract very little scan traffic — whereas any signal of activity can draw attention.

This helps explain why early IPv6 telescopes saw little traffic; scanners weren’t wasting effort on unremarkable, unknown subnets. Now, however, with better target generation, scanners actively seek out newly announced or hinted-at IPv6 space. Our decision to actively expose ‘honeyprefixes’ via multiple channels directly leveraged this fact — our telescope essentially shone a spotlight on IPv6’s dark corners to reveal the lurking scanners.

The largest IPv6 telescope in action

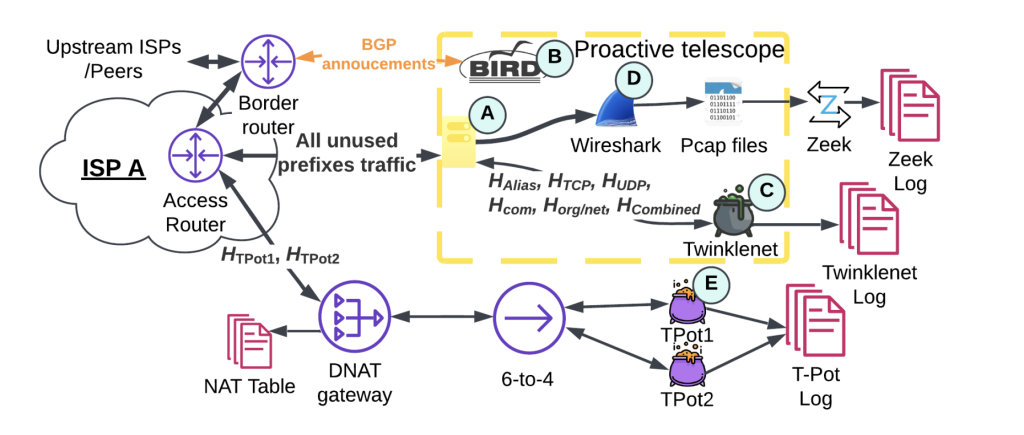

Our CoNEXT 2025 study introduced a ground-breaking IPv6 network telescope deployed in a production ISP network — the largest of its kind ever built. In essence, a network telescope (or ‘darknet’) is a chunk of unused address space used to catch unsolicited traffic (often scans, probes, or network traffic backscatter).

Traditional IPv6 telescopes are passive, quietly listening on unassigned addresses for any incoming packets. This new telescope took a more aggressive, proactive approach — we broadcast the presence of the otherwise dark addresses to the Internet to entice scanners.

Over a ten-month deployment, our telescope (occupying a /32 IPv6 prefix in a regional ISP) collected over 600 million unsolicited IPv6 packets originating from nearly 2,000 different ASes — a scale unprecedented in IPv6 measurement. By comparison, previous IPv6 telescopes were far smaller (for example, covering a /56) and observed much less traffic. This massive new vantage point has yielded the richest view yet of how IPv6 scanning operates in the wild.

Crucially, in this work, we combined multiple signal ‘lures’ across the network stack to maximize its visibility. Rather than simply waiting in silence, the telescope announced itself to the world by:

- Advertising BGP routes for several sub-prefixes to signal active IPv6 space.

- Registering DNS records pointing to the telescope’s addresses.

- Obtaining TLS certificates for some telescope addresses from public Certificate Transparency (CT) logs.

- Seeding the addresses into public IPv6 hitlists.

In addition, we ran honeypot servers on those addresses to answer connection attempts (to appear like live hosts). To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive set of IPv6 scan ‘attraction’ techniques ever deployed in a single experiment.

By deploying dozens of these instrumented ‘honeyprefixes’ (IPv6 /48 subnets within the /32, each with a different combination of lures), we created a telescope array to systematically test which signals attract which scanners. We also operated two traditional passive IPv6 telescopes in parallel for comparison. The results were clear — the proactive telescope vastly outperformed passive ones, pulling in the biggest share of scan traffic.

In fact, the primary proactive telescope (nicknamed NT-A) accounted for about 70% of all IPv6 scan traffic observed across the study, and from the most diverse set of source networks. The other two passive telescopes, a /32 deployed within a university network, and a smaller /48 telescope, captured orders of magnitude less unsolicited traffic and scanner diversity. This disparity underscores that visibility alone isn’t enough; proactive signalling is essential to attract a broad and representative set of IPv6 scanners.

Beyond passive telescopes: Luring scanners with BGP, DNS, and TLS

Each proactive ‘signal’ played a role in widening the capture net.

BGP announcements proved especially powerful — besides signalling that a prefix is live, announcing more specific /48s gave scanners a narrower range to focus on (versus the whole /32), increasing the chance they’d hit the right addresses. BGP-advertised subnets quickly started receiving probe traffic once they went public. DNS registrations helped attract scanners performing zone walks or reverse DNS lookups. TLS certificates (and their CT log entries) drew in actors mining those logs for new host addresses.

And of course, running honeypot services on the telescope addresses made them appear as real, responsive hosts when pinged or connected to, encouraging sustained scanning. By stratifying the deployment (different prefixes with different combinations of BGP, DNS, TLS, and so on), we could analyse what techniques caught which scanners. Their experimental setup — 27 instrumented subnets — is highly novel and provides ‘A/B testing’ for scan attraction methods.

In total, the proactive telescope detected 654 million IPv6 scan packets over the experiment, originating from around 259,000 unique IPv6 addresses in 1,900+ ASNs worldwide. This represents the most extensive view to date of who is scanning IPv6 and how.

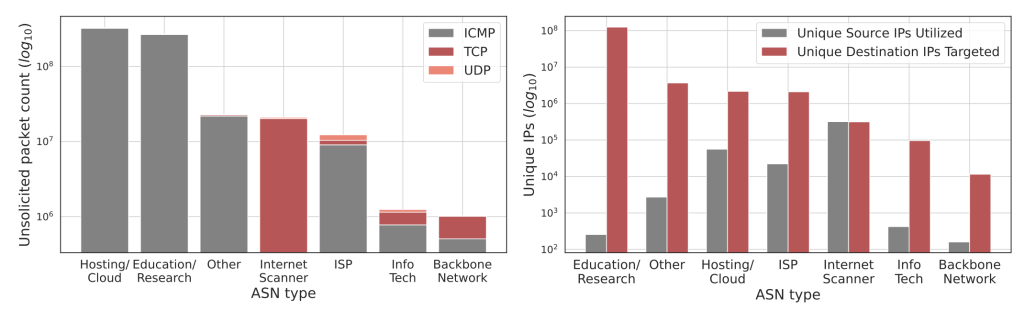

Interestingly, over 90% of the captured scan packets were ICMPv6 echo requests (pings). Despite the telescope being capable of responding to Transport Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) ports, most scanners simply ‘pinged’ to test which hosts were alive — a strategy likely aimed at quickly mapping out active addresses before deeper probing.

However, there was significant variation across scanner types. The study observed that dedicated ‘Internet scanner’ services (for example, research projects or search engine crawlers) were far more likely to use TCP and UDP-based probes, whereas cloud-hosted or opportunistic scanners stuck mainly to ICMP ping sweeps. This suggests that different actors have different goals and sophistication — some perform full port scans on targets, while others just sweep for any responsive IPs.

Another remarkable tactic was uncovered: Some IPv6 scanners spread their probing across extremely large source address ranges. One prolific actor was found to rotate through an entire /30 IPv6 block for its scanning activity. (A /30 contains a staggering ~298 addresses).

In contrast, another set of scanners from a cloud provider conducted their scans from within a much smaller /96 block. This divergence has big implications for defenders: An attacker using millions of IP addresses from a huge prefix makes it very hard to identify or block them by IP alone. If you block one IP, they can pop up with another from the same /30.

On the flip side, aggressively blocking a /30 could mean blackholing legitimate users in that entire range. We emphasize that security teams need to be mindful of IPv6 address allocation sizes when creating blocklists. Practices from IPv4 (like blocking a /32 or /24 to stop a scanner) don’t directly translate to IPv6, where the offending addresses might span a much larger network block.

Implications for IPv6 security and network defence

This study provides actionable insights for network operators and security professionals grappling with IPv6. First, it’s a wake-up call that IPv6 is no longer a backwater free from scanning — it’s very much being actively scanned and probed at a large scale.

The observed 100 times growth in scan traffic over two years means IPv6 scanning has entered an exponential phase. Attackers are clearly investing resources into mapping out IPv6 networks, likely seeking vulnerable services or misconfigurations. Defenders should not ignore IPv6 traffic in their intrusion detection systems and logs, assuming ‘nobody scans IPv6.’

In fact, the diversity of sources (nearly 2,000 ASNs) shows that scanners are globally distributed; many are coming from cloud platforms (AWS, Azure, and so on), which makes attribution tricky. Hosting and cloud providers constituted over half of the unsolicited IPv6 traffic observed, with Amazon AWS and a Chinese research network (CERNET) being the top two sources by volume.

This indicates cloud infrastructure is a hotbed for IPv6 scanning activity, either due to misused customer virtual machines or ambitious research projects. Network owners might need to collaborate with cloud providers to curb abusive scans, or at least adjust their threat models to treat inbound traffic from cloud ASNs with scrutiny.

The findings also highlight the importance of multi-faceted monitoring. If you rely solely on passive sensors, you could be missing a huge portion of IPv6 scanning that only targets ‘known’ addresses. Deploying proactive telescopes or honeypots (even just announcing a bait IPv6 prefix via BGP or DNS) can greatly enhance visibility into who’s knocking on your network’s door.

This can help early-detect large-scale scans or new scanner techniques. For instance, if you announce an unused /48 and suddenly see a flood of pings, it might reveal a scanner that monitors route announcements — valuable intelligence on attacker behaviour. Security teams can use such insights to pre-empt attacks (for example, knowing that a new subnet announcement will attract scans can help you prepare defences accordingly).

Lastly, the observation about scanners’ address dispersion (using /30 vs /96 blocks) is crucial for designing IPv6 defence measures. It suggests that IP-based rate-limiting or blocking in IPv6 should consider prefix sizes. For example, if suspicious traffic comes from a wide range of addresses all within the same large allocation (say, a /32 from a cloud provider), it might actually be one campaign. Defences could focus on higher-level patterns (like user-agent strings, traffic behaviour, and so on) rather than individual IPs.

Conversely, overly broad blocking of IPv6 space could cause collateral damage if legitimate users share that space. In IPv6, security filters need to be more surgical and context-aware.

Hammas Bin Tanveer works on network performance at SpaceX Starlink and completed a PhD in Computer Science at the University of Iowa’s SPARTA Lab. His research spans IPv6 scanning and censorship measurement, and empirical analysis of satellite networking systems.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.