In September 2025 I wrote an article about Starlink and geolocation. This work was prompted by a question about the makeup of Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in Yemen. The data analysis point to Starlink having six million users, or 60% of the estimated user population of Yemen.

This result was easily classified as ‘dubious’. Analysis of ISP market share in other economies gave results that matched conventional assumptions. It also matched the few instances where good data on this topic of ISP market share is publicly available. I started looking for other factors that may have impacted the Yemen result.

The factors I speculated about in that article included shipping — where crews use Starlink on a global roaming services — and aircraft in flight using Starlink to provide in-flight Internet services to passengers. Starlink publish a map that assigns every IP address they use into an economy. That map includes any IP addresses that are used by ships and aircraft voyaging through international areas. However, this factor could not account for an extra four to five million Starlink users that popped up in Yemen.

I speculated about cross border global roaming, as neighbouring Saudi Arabia has not reached any agreement with Starlink for the provision of services in Saudi Arabia. Starlink does permit roaming, through its roaming service plan. If, however, you roam to a location where Starlink is not authorized for use, Starlink may not provide any service, or may terminate the service after a period of two months.

I also speculated about community redistribution and ‘hotspots’ based on Starlink. Here a single service may be used by hundreds of individual users. Starlink would count this as a single service. The ad-based measurement system, which counts instances of browsers on separate devices, would ‘see’ the entire collection of end users in the same way as the measurement system counts individual users behind various forms of Network Address Translation (NAT).

All of these factors were plausible, but none really seemed to match what was visible in the data. Starlink users in Yemen were just getting a disproportionately high number of the ads placed on to end systems located in Yemen.

A second look

Civil unrest can often cloud measurement data. Some measurement systems, including ours, make relatively sweeping assumptions about the stability of both end user and network service behaviours, and assume that the changes that occur from day-to-day are minor.

The data behind the market share of ISPs in Yemen assumed that all retail ISPs had a similar profile of presentation of online ads to end users. This assumption allowed us to make the inference that the count of ads per ISP was approximately aligned to the market share of each ISP.

There are weaknesses in this approach. Firstly, there is a mismatch in terminology.

A mobile network’s count of ‘users’ is closer to the count of service subscriptions, or the count of active SIMs installed in mobile devices. It’s probably a reasonable assumption that each device has a single end user, and that the count of subscribers is reasonably well aligned to the count of end users.

A residential or enterprise ISP service is different, and there is the general expectation that there is more than just one end user behind each ISP service. Here the terms ‘subscribers’ and ‘users’ encompass different concepts, and the counts of these two concepts will necessarily differ.

What about Starlink?

One would expect that Starlink is a lot like a retail ISP. The number of Starlink end users would exceed the number of ‘services’, but by a factor that would be similar to other forms of fixed line access.

Secondly, user behaviour necessarily changes in times of civil unrest and conflict. This sounds like a truism, but it has impacts on ad-based measurement.

Mobile services are often more resilient than fixed line services at such times, and users may turn to various forms of connection sharing. This includes ‘hotspot’ redistribution of mobile services to Wi-Fi, so the assumption of a single mobile service roughly equating to a single user may break down.

The same applies to Starlink.

The Starlink service agreement includes the provision: “If you purchase a Priority Plan, you may resell access to the Services as community Wi-Fi or a ‘hotspot’ to third-parties”. So, it is likely that when ‘normal’ ISP services are disrupted due to civil unrest, people may turn to a shared service that provides them with vital information and services. The implication is that the number of users of Starlink services in an economy may rise in such circumstances even though the number of services may not rise to the same extent.

A couple of relevant announcements

Yemen appears to be in such a state of civil unrest and there are a couple of relevant announcements that relate to the use of Internet services that I’ve discovered since I wrote the original article.

The first is the announcement made on 27 April by the “internationally unrecognized Houthi-run Ministry of Telecommunications that it has ordered all citizens and entities in territories under the group’s control to surrender their Starlink satellite Internet devices by 1 May 2025”. As this article observes: “Starlink’s satellite-based high-speed Internet offers rare connectivity in Yemen, where war and infrastructure damage have crippled traditional services. The Houthi ban reflects their efforts to control information flows amid the ongoing conflict”.

The second is an announcement by the Yemeni Houthi militia on 30 June 2025 that it had banned all Google ad services on Yemen Net, the major Yemeni fixed line and mobile ISP, that it reportedly controls.

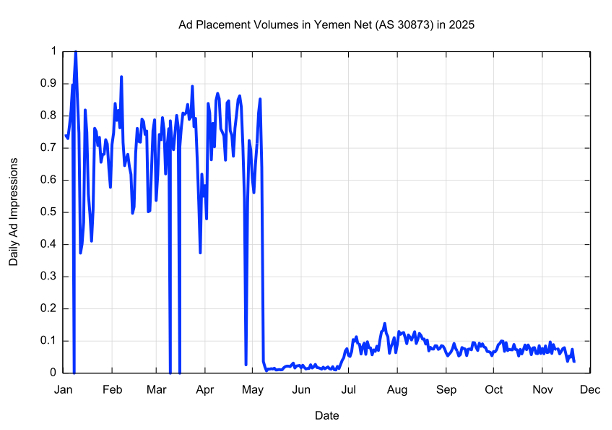

This second announcement is critical for our form of ad-based measurement. We can observe the effects of this announcement in the ad placement volumes, as seen by subscribers of Yemen Net (AS 30873). The data shows that impressed ad volume for this ISP dropped by 90% in early May (Figure 1).

Presumably the number of users of Yemen Net has not changed substantially (we cannot tell from here, as the only tool we have is ad placement data), but the ad volumes for this ISP have plummeted.

Can we ‘restore’ the calculation of market share for Yemen?

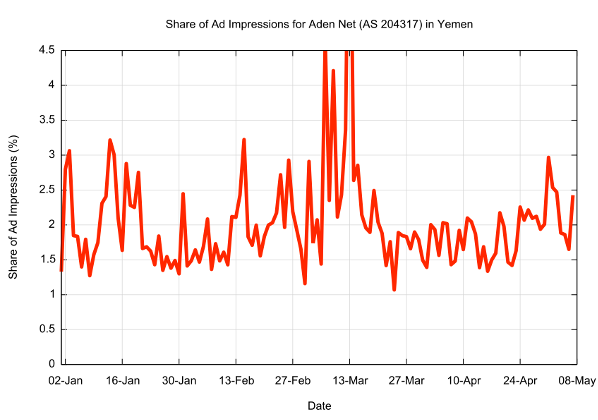

In the absence of any other data, we can use the observation that the user population of another Yemeni ISP, Aden Net. The Aden Net data has been relatively steady in the first four months of 2025, at an average of 2.03% of the total number of ads presented to users located in Yemen (Figure 2). Evidently, the port of Aden is not under Houthi control at present, nor is this particular ISP under Houthi control.

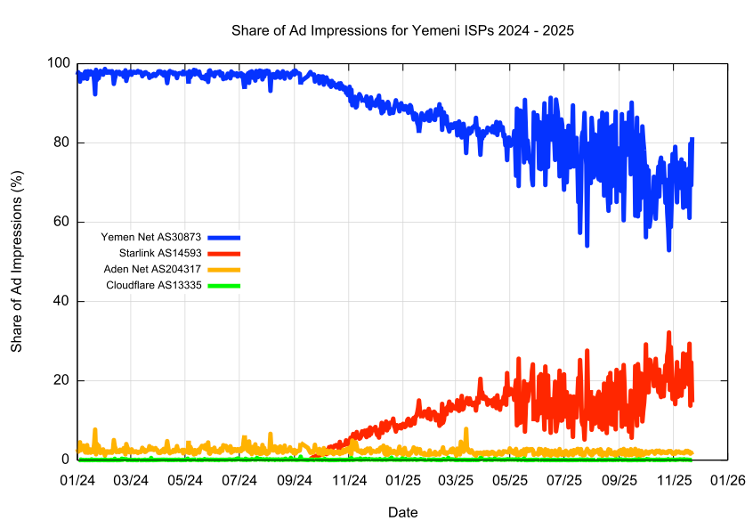

If we project this average 2.03% market share for Aden Net number forward, and use a random noise factor of +/- 0.4% for each day, we can derive a ratio between the count of ad impressions and the estimate of the network’s user population. This same multiplier that is used for Aden Net users can be applied to the other ISPs who service Yemeni users, namely Starlink (AS 14593) and Cloudflare (AS 13335). This can provide us with an estimate of the total user population served by these three service providers. We also have a stable estimate of the total population of Internet users in Yemen, so we assume that the balance of Yemeni users are served by Yemen Net (Figure 3).

The daily figures for the share across the Yemeni ISPs are far noisier from June 2025 onward. Instead of deriving these daily numbers from 28,000 ad impressions per day, we are using the data from Aden Net, which receives around 600 ad impressions per day. The multiplicative factor used to derive the far larger Yemen Net numbers amplifies the daily variations in the estimated populations of Starlink and Yemen Net users. It’s not exactly satisfactory, but it’s the best that can be done with partial data in this case, and better than simply discarding the Starlink use data for this Yemen.

Conclusions

The initial analysis of the anomalous data for Starlink users in 20 economies led APNIC Labs to override the Starlink geolocation data that refers to those 20 economies. Instead, we assigned an ‘unclassified’ designation to this part of the Starlink geolocation data.

This second look at the situation in Yemen has given us a lot more confidence in the fidelity of the Starlink geolocation data. As a result I’ve removed the override I installed at the end of September and restored the original data and derived tables of ISP market share for these 20 economies.

There is still an outstanding geolocation question concerning ships at sea, airplanes in flight, and details of the ways Starlink manages mobility and roaming. However, Starlink is important enough in the overall picture of market share in many economies that it’s unwise to arbitrarily reclassify this Starlink data for these 20 economies into the ‘unclassified’ designation. Accordingly, I’ve restored the original data to the reports.

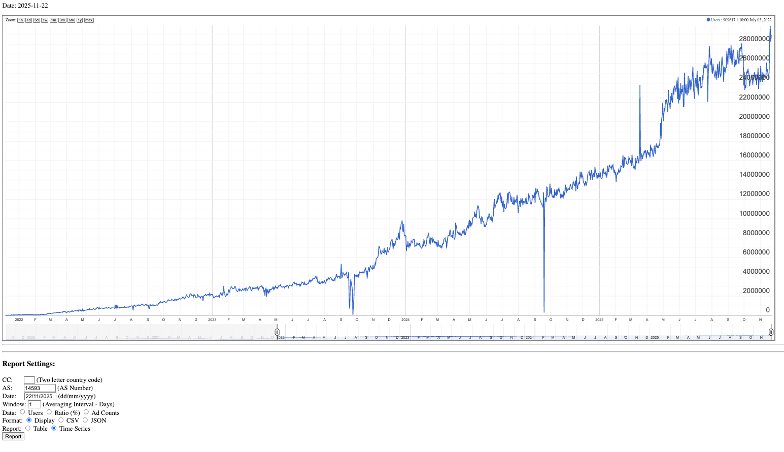

And what of the number of Starlink users worldwide? This data points to a current base of 2.3M users, and a growth rate of 800,000 users per year so far (Figure 4).

The reports of estimates of the user populations of networks can be found at APNIC Labs.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.