Cybersecurity professionals, researchers, and network operators from across the Asia Pacific gathered at APNIC 60 for two sessions co-organized by FIRST and APNIC. These sessions aimed to strengthen regional collaboration and share actionable insights on emerging threats.

This post covers highlights from the first session, held on Wednesday, 10 September 2025, including presentations on Advanced Persistent Treat (APT) activity in South East Asia, Search Engine Optimization (SEO) spam and keyword hacking, and a new open-source platform to improve cyber resilience in academic networks.

Pandas in the wire: HoneyMyte’s trail of espionage in ASEAN

Speaker: Fareed Radzi, Kaspersky

Fareed works with Kaspersky in Malaysia on malware and forensics in cybercrime, monitoring over 900 groups and operations, with a focus on crime groups and government-backed actors. His team has ten years of experience providing threat intelligence to customers and partners worldwide.

A multi-year investigation

He presented the results of a multi-year investigation into an advanced threat campaign seen in South East Asia, attributed with a high degree of confidence to a group called HoneyMyte (by Kaspersky). In the media, the group has been called Mustang Panda, RedDelta, Bronze President, Stately Taurus, Earth Preta, or Camara Dragon.

This Chinese-speaking Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group has been active since 2014. Their motivation appears to be mainly espionage and intelligence gathering, targeting government and military contexts, but also research and academic sectors, the ‘soft underbelly’ of government-funded activity. They have also been known to target Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and telecommunications companies.

Their work has been seen throughout South East Asia, but the most affected economy in the region is Myanmar. Infections have also been seen in Thailand, the Philippines and Singapore.

A common attack pattern

A common attack pattern used by the group starts with a spear-phishing email, installing a backdoor. This can be an MSI installer, archive file (zip, rar, or iso, for example), or malicious shortcut links. Their emails typically mimic government official communications, tailored to the economy (for example, in Thai for Thailand, Burmese for Myanmar).

The attack vector depends on the user running JavaScript, which unpacks and executes the compressed file, and sideloads the ToneShell DLL. A related attack vector has been seen using USB worms (like Tonedisk) to get into air-gapped networks on USB devices carried from an infected computer into the air-gapped space.

After the initial compromise, HoneyMyte maintains system access through Remote Administration Tools (also called Remote Access Trojans, or RATs). While HoneyMyte has been observed using ten different RATs to achieve backdoor systems access, four continue to be used in active attacks, including ‘cracked’ editions of enterprise adversary simulation products. The code implementing these backdoors can be treated like a signature; analysis of that signature helps to associate specific threat actor groups with specific tools.

Backdoor code has usually been highly obfuscated, with nested layers of malware, and shows signs of constant evolution. However, reverse-engineering and analysis is still possible. Fareed has shown quite extensive ‘lineage’ between the different attack versions over time. Wrapping malware in additional malware allows for the differentiation of execution, key capture, document analysis and infection commands.

For example, CoolClient is used alongside Toneshell to give extra capabilities and as a ‘backup backdoor’. Kaspersky researchers have seen Bitdefender, VLC, SangFor and Ulead PhotoImpact being abused to side-load CoolClient DLLs. This malware has been seen in Kaspersky telemetry worldwide, but 2025 infections of note included Russia and Mongolia, as well as economies in South East Asia.

QReverse (also known as Talos Trojan) is similar to CoolClient, but adds screen sharing functionality. It can also be used to steal information about user identity and operating system versions.

The capabilities in RATs deployed in HoneyMyte attacks strongly suggest specific system targeting, aiming for documents and credentials. This is not considered a lateral movement threat, but rather a targeted attack focused on information on the infected system.

Post-compromise, HoneyMyte attacks gain persistence using system registries, scheduled tasks, and Windows services. Fareed shared an example from the Myanmar government in which QReverse was used to download and schedule a batch script. The script collected network and system information, uploaded it using File Transfer Protocol (FTP), and then covered its tracks. In another example, a Powershell script was used to find and compress documents with specific file types and upload them to an FTP server.

Kaspersky has also seen attacks that target browser cookies and saved login data, which is more typical of lateral movement threats.

Awareness and hardening

HoneyMyte doesn’t stop. Fareed expects the group’s espionage-focused attacks to continue and expand in our region and around the world, reusing effective techniques while evolving and improving their tools.

The risk from APT actors certainly resonated with at least one audience member, who asked about the visibility of ‘spill over’ effects into other economies. Fareed responded that, at this time, there was insufficient evidence to say with any authority. He noted some signs of lateral movement, but said it appeared to be specific to the original target. Fareed called on the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) and Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) communities to devote more attention to awareness and hardening as a way to protect against these types of threats.

Watch Fareed’s APNIC 60 presentation now:

Recent advances in keyword hacks and SEO spam tactics

Speaker: Charuka Damunupola, Sri Lanka CERT

Charuka’s presentation looked at malicious monetization in the Search Engine Optimization (SEO) space. At first glance, this might seem like a minor issue, but it can undermine search engine trust and help threat actors generate income that funds more serious attacks.

What is keyword hacking?

Charuka described an incident experienced by one of the constituents of the Sri Lanka CERT. A government agency saw ‘unusual’ results coming up in searches: Japanese language responses were being returned in response to searches relating to their core business and activity.

The attacker managed to subvert both keyword matching and user intent signals, causing Google (in this instance) to surface Japanese-language content. This isn’t just a problem affecting .gov.lk domains, but part of a global threat. Keyword hacking is also called ‘Japanese Search Spam’ (or Chinese, or some other language).

Attackers create pages filled with autogenerated, product-specific keywords, often related to counterfeit e-commerce and scam websites. Unlike other attacks, it usually isn’t related to strategic interests, but rather to financial gain from e-commerce for goods bought and sold online.

Chinese, Korean and Japanese language communities have massive online consumer markets, making them particularly attractive targets for keyword attacks. By linking to their own sites, attackers take advantage of normal SEO ranking algorithms to gain higher trust in their sites, which in turn boosts their visibility in search results.

Incident analysis

Charuka and the Sri Lanka CERT began their analysis with simple Google searches using popular Japanese language search terms, bound to the ‘.gov.lk’ domain of the affected constituent. Results included titles, snippets, and links to e-commerce websites, all found in the victim’s domain. The team also used the Google Search Console tools like ‘Fetch as Google” and URL inspection.

They found that attackers appear to have taken control of the sitemap.xml structure and associated metadata in a site compromise. Since sitemap.xml is often managed by Content Management Systems (CMSs) directly, it has low visibility to administrators. Changes to the sitemap.xml also do not affect the user experience for users who are legitimately interacting with the website.

However, indexers, like Google, capture the file, embedded sitemap, and associated linkages. Because indexers assume that the sitemap is controlled by the site owner, they apply the same trust ranking to onward links as they would to the .gov.lk site. This, in turn, boosts the e-commerce sites’ visibility.

Charuka also showed how the team found encrypted PHP code had been added to the core WordPress ‘index.php‘, which revealed payload-fetching URLs when decrypted. This change suggests an active takeover of the CMS (WordPress in this case, but similar attacks have affected other popular systems like Drupal and Magento) behind the website. Additional changes granted root webshell access, providing attackers with a backdoor into the system. Charuka explained that lower-level SEO monetization, in turn, can lead to more serious attacks.

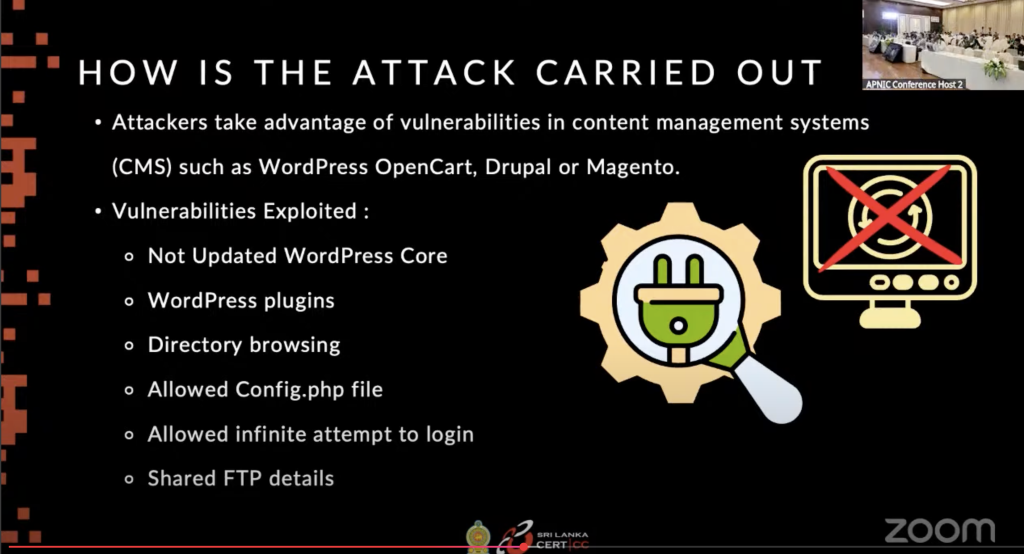

How it’s carried out

The key point here is ‘cloaking’. The website markup is modified to show ‘correctly’ to ordinary users, but a self-identified ‘crawler’ matching the HTTP header pattern is shown the malicious content. To find traces of the infection, you must access the site as an indexer would. The attack uses known risks of un-updated core software, vulnerable plugins, improperly configured directory browsing, and writable PHP files.

In the long term, the website’s reputation can plummet, and your hosting provider can suffer damage. This, in turn, leads Google to blacklist both the tenant and host. Revenue and traffic both suffer, taking months to recover.

How to verify the site affected

Charuka suggests starting with site analytics provided by Google Search Console for your own site’s search profile to check the site’s responses. Also, look at flagged security issues, especially major concerns like site redirection.

Remediation

To remediate a site affected by a keyword hacking attack, Charuka recommends that Google Search Console accounts be audited, and newly granted or unrecognized access be removed. He also suggests checking the sitemap.xml, robots.txt, .HTACCESS and PHP files, especially recently modified files.

Affected systems should be reinstalled, followed by a deep forensic review. From there, the search response state can be cleaned, and you can let Google and other indexers reindex your site.

Prevention

Charuka emphasized the importance of keeping up-to-date with system patches and scans, and using two-factor authentication (2FA). He also encourages subscribing to an external security review as a periodic service.

While keyword hacking can seem like an apparently simple compromise for financial gain, it has massive risks to your reputation and to your hosting provider. In the case of hosted government services, a successful attack can cause massive reputational harm to the national structure.

Slides: Recent Advances in Keyword Hacks and SEO Spam Tactics(2 MB)

Watch Charuka’s APNIC 60 presentation now:

Enhancing academic cyber resilience: Integrating T-Guard into ACAD CSIRT services

Speaker: Charles Lim, Swiss German University

Charles spoke about the challenges faced by academic community networks and their specific CSIRT needs, highlighting a new threat detection and response system developed using an open-source model. The goal is to improve cyber resilience in the education and research sector.

Charles has depth in Asia Pacific cybersecurity research, having initiated the Indonesian Honeynet Project, and is a member of the Digital Forensics Association of Indonesia, as well as leading cybersecurity at the Swiss German University (SGU).

The university sector has high levels of exposure to risk, according to Charles, because of the combination of threat advances, lack of campus operational cover, and prioritization issues within the budget constraints of the institution. These complexities are amplified by the legal landscape for educational institutions, which are ‘just different’ in terms of their authority and governance over associated bodies like student colleges, research companies, and similar bodies. Rather than a single integral network, an academic network is often multifaceted.

Of 4,500 universities in Indonesia, only 1,500 teach Information and Communications Technology (ICT), and of these ,only 20 have a CSIRT. However, all tertiary institutions are now bound by the UU Personal Data Protection privacy law, which places legal obligations on the institution to guard student data privacy. These new obligations may lead to the creation of new CSIRTs.

SGU started its non-governmental Academic Computer Security Incident Response Team (ACAD CSIRT) in 2021, aiming to unite the university response across the threat landscape, promote training, and engage with the global community.

ACAD CSIRT is acting as a coordination body between the Ministry of Education, the National Cyber and Crypto Agency, and the university sector. It now organizes cyber competitions, training, workshops, and broader engagement activities.

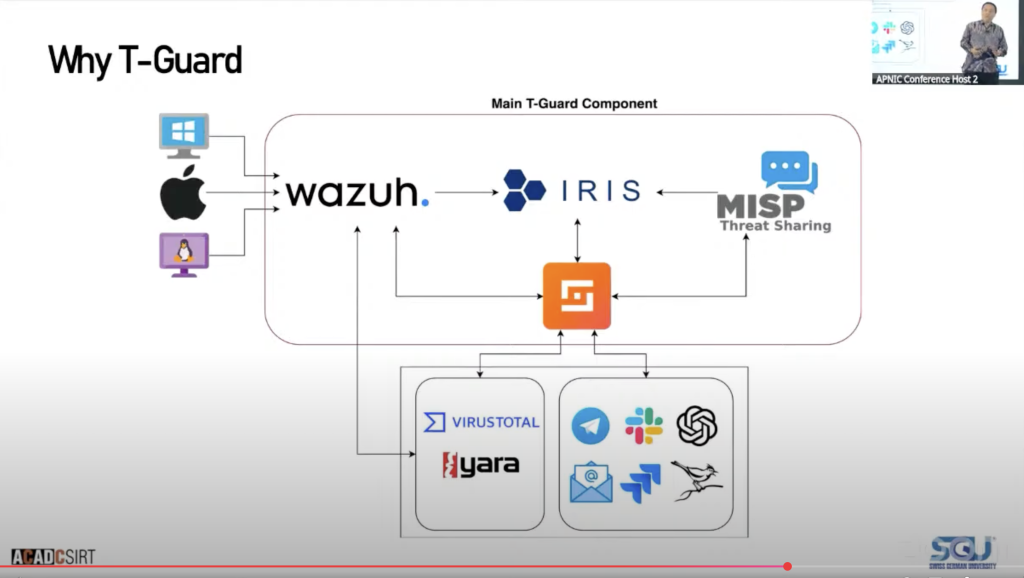

The lead development being showcased at APNIC 60 is the T-Guard product, an open source advanced threat detection and response platform. It’s being offered as a turnkey service for universities through the ACAD CSIRT community. Charles says there are already expressions of interest from 160 universities, and five early adopters have deployed the system.

T-Guard provides real-time monitoring, automated alerting, and customizable dashboards. It can do asset security management and ensure threats like site defacement are detected and addressed quickly. It integrates a trouble ticketing system, an automation framework, and a threat-sharing system integrated with scanning and protection tools. Other analysis tools and communication platforms can be plugged in to give a cohesive service delivery.

According to Charles, the motivation behind T-Guard was to avoid vendor lock-in and offer reduced licence costs. There was a strong desire to be platform-neutral and manage Windows, macOS and Linux systems within a single SOC platform. As the tertiary sector includes so many complex models of institutions, it had to support multi-tenancy to allow smaller, low-resource institutions and research agencies to benefit from their own hosted portals.

An initial offering supports up to five user endpoints as a starter package with a month of log retention. This supports compliance with the UU PDP, satisfies legal obligations, mitigates risk, and promotes information sharing across the sector.

Slides: Enhancing Academic Cyber Resilience – Integrating T-Guard into ACAD CSIRT Services(1 MB)

Watch Charles’ APNIC 60 presentation now:

Watch, read, and dive deeper

These presentations highlighted the evolving tactics of threat actors, the risks of SEO-based compromises, and new tools to strengthen cyber resilience in academic networks. To learn more, watch the embedded videos, explore the slides, and visit the APNIC 60 conference website for recordings of all sessions.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.