This post was co-authored by Antonio Prado.

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are physical interconnection facilities where multiple Autonomous Systems (ASes) exchange IP traffic. Instead of routing traffic through expensive upstream providers, networks can peer directly, reducing cost, latency, and dependence on transit.

Most IXPs consist of high-performance switching infrastructure, route servers, and optional measurement and monitoring tools. Beyond technical efficiency, IXPs support national resilience, improve user experience by keeping traffic local, and serve as critical coordination nodes in times of crisis.

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are physical interconnection facilities where multiple Autonomous Systems (ASes) exchange IP traffic. Instead of routing traffic through expensive upstream providers, networks can peer directly, reducing cost, latency, and dependence on transit.

Most IXPs consist of high-performance switching infrastructure, route servers, and optional measurement and monitoring tools. Beyond technical efficiency, IXPs support national resilience, improve user experience by keeping traffic local, and serve as critical coordination nodes in times of crisis.

However, despite their foundational role in Internet architecture, IXPs often operate in the shadows of public awareness and policy frameworks. As a result, their vulnerabilities tend to be underestimated. In this post, we explore what happens when IXPs fail and why classifying them as critical infrastructure is not just a formality, but a systemic necessity.

The visibility paradox

Despite their crucial function, IXPs are often invisible in both public discourse and infrastructure policy. This ‘visibility paradox’ creates three systemic risks:

- Economic optimization over resilience: Traffic is increasingly routed through major IXPs due to cost and efficiency, concentrating risk.

- Dependency of smaller networks: Many small ISPs depend on a single IXP to access affordable connectivity and major content providers.

- Topological centralization: A handful of physical IXP locations carry disproportionate amounts of regional traffic, creating structural vulnerabilities.

When IXPs go down: Real-world examples

Let’s examine what happens when an IXP fails. Below are real incidents that illustrate systemic dependencies on these nodes.

Building resilience on a budget

In 2000, an attempt was made to block the launch of the Kenya Internet Exchange Point (KIXP). Only strong advocacy from the local technical community preserved it. Since then, KIXP has reduced national transit costs by over 70% and improved routing stability despite limited resources.

Total isolation

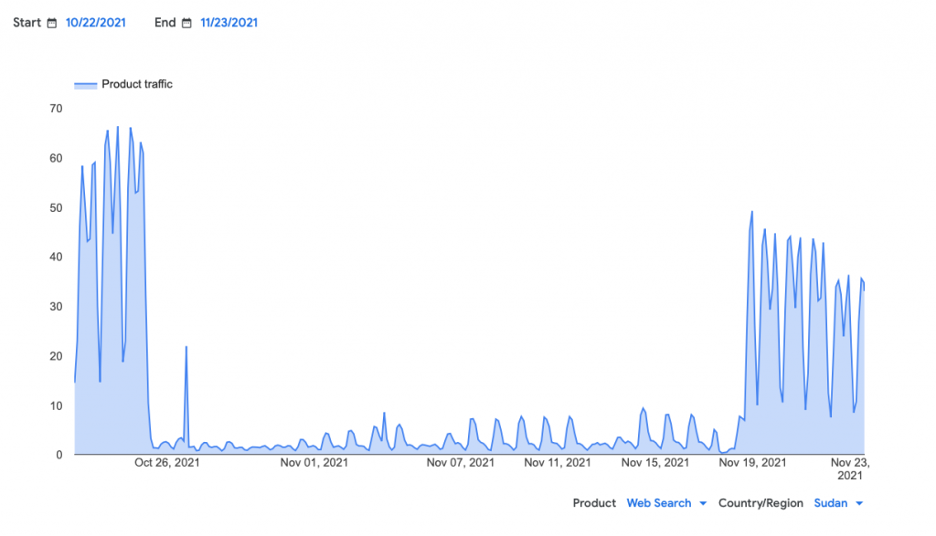

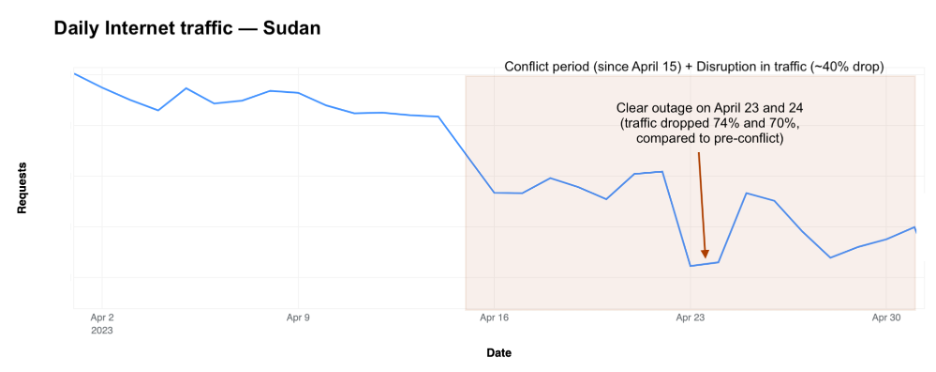

During the 2021 – 2023 Internet shutdowns, Sudan’s lack of a resilient local IXP meant that even internal traffic was cut off. The absence of domestic interconnection rendered the economy completely dependent on international links, which are vulnerable to disruptions

Multistakeholder-led redundancy

Brazil’s IX.br, coordinated by CGI.br — a multistakeholder body with balanced participation from the public sector, private sector, civil society, and academia — operates 35 IXP locations. During the 2020 pandemic surge, its wide geographical coverage helped absorb massive traffic increases. Its model shows that collaborative coordination and decentralization enhance systemic resilience.

Power failure, wide impact

In 2018, a power outage at Interxion FRA5, which hosts a major DE-CIX switch, caused partial IXP failure. The resulting loss of Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) visibility affected routes across Europe. Even with built-in redundancy, this incident highlighted how dependent many ASes are on a single physical location.

Wide-scale re-convergence

A 2021 software fault at LINX caused traffic to re-converge at scale, hitting smaller ASes hardest. While routing recovered, the temporary instability caused degraded performance and demonstrated how IXP events cascade beyond borders.

Traffic collapse

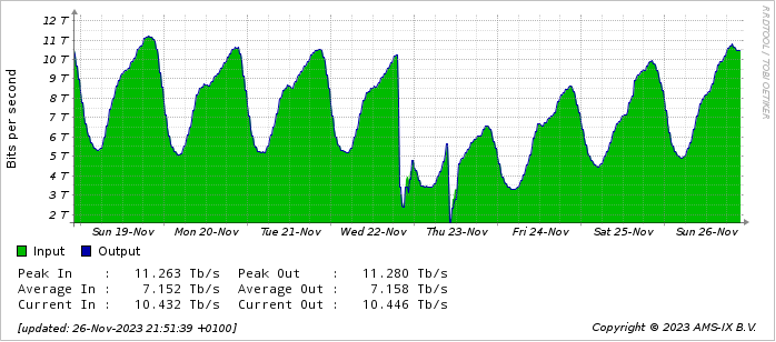

In November 2023, the Amsterdam Internet Exchange (AMS-IX) experienced two service interruptions totaling over five hours. During the outage, traffic dropped from 10TBps to 2TBps. The effects were felt across European providers reliant on the exchange.

Economy-wide impact

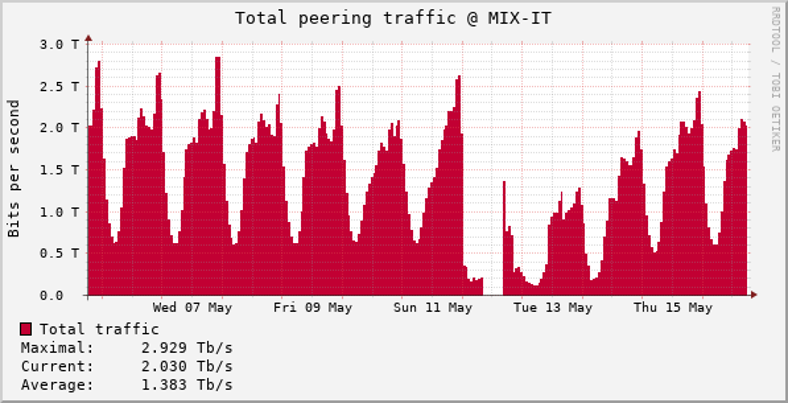

On 12 May 2025, a fault at Milan Internet Exchange (MiX) disrupted the reachability of several local services, leading to slowdowns and outages nationwide. This reinforced MiX’s critical role in Italy’s Internet architecture.

These examples show that IXPs are more than just technical tools, they play a critical role in keeping the Internet stable. If one IXP fails, it can cause major routing problems, network congestion, and service disruptions. This highlights how much Internet resilience depends on strong, well-governed, and resilient local IXPs.

IXPs and resilience

When thinking about resilience on the Internet, most discussions revolve around backbone providers, submarine cables, or DNS root infrastructure. However, IXPs quietly play a key role in buffering crisis scenarios by localizing traffic and preserving critical connectivity, especially under stress.

They also dramatically reduce dependence on long-haul transit routes. By allowing local networks to exchange traffic locally, they provide both latency improvements and a powerful structural advantage — autonomy. In normal conditions, this brings greater efficiency. During major infrastructure disruptions this autonomy supports resilience. In some cases, local operators managed to maintain partial Internet functionality in affected areas by relying on local peering. Traffic that would otherwise be routed through international transit providers remained within local IXPs, reducing exposure and dependency. In contrast, economies with underdeveloped peering ecosystems or where interconnection is over-centralized are more exposed to routing fragility.

IXPs as shock absorbers

The impact of external shocks, energy failures, cyberattacks, or embargoes, is often amplified when IXPs are missing or poorly governed. Let’s take some recent examples.

- Kenya: A power blackout in 2023 disrupted Internet access across the economy. While multiple providers had redundant international capacity, the absence of robust local peering meant that local traffic had to rely on external routes, which degraded performance and reachability.

- Sudan: Recurrent outages and blackouts have shown that centralized international dependencies make restoration harder. A stronger local IXP ecosystem could have helped mitigate isolation.

- The Iberian Peninsula: Analysis of a major blackout in 2025 revealed that Portugal’s Internet traffic dropped by up to 90%. Spain’s traffic, while impacted, held up better, partly due to its stronger IXP footprint, including Madrid-based ESpanix and DE-CIX Spain.

These cases illustrate that IXPs do not just route packets, they absorb impact.

What must change to recognize IXPs as critical infrastructure?

Despite their central role in routing stability and local interconnection, IXPs are still rarely classified or treated as critical infrastructure. This gap creates regulatory blind spots and operational fragility, especially in economies where one IXP dominates the national traffic exchange. In this final part, we look at the governance, policy, and operational frameworks that must evolve to ensure IXPs are recognized and supported as the resilient backbone they already are.

Transparency before scale

Many IXPs start small, often as collaborative efforts between local ISPs, universities, or Network Operator Groups (NOGs). As they scale, however, their governance model may remain informal or unclear. This creates risks when traffic concentration grows.

Critical IXP governance principles should include:

- Neutral ownership (no single commercial entity with veto power)

- Multistakeholder boards, including operators, academia, and civil society

- Published traffic statistics, membership policies, and pricing models

- Clear failover plans and infrastructure redundancy

Without these, IXPs become invisible single points of failure, both technical and institutional.

Technical hygiene

For IXPs to be resilient, they must also be secure and observable. This includes:

- Mandatory route server filtering with prefix and AS-PATH validation

- RPKI-based filtering and support for BGP monitoring tools

- Public looking glass or IXP manager views

- Participation in the Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security (MANRS) IXP Program.

These are not ‘nice to have’ extras. In a world of BGP leaks, hijacks, and targeted attacks, they are baseline requirements. Greater observability also enables national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and researchers to act faster during incidents, from mis-routing to Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks affecting IXP-connected networks.

From recognition to resilience

Very few national legislations include IXPs in their critical infrastructure lists, often focusing instead on physical cable systems, data centres, or DNS infrastructure. However, the strategic value of IXPs calls for their inclusion in:

- Economy-wide cybersecurity strategies

- Regulatory frameworks for network resilience such as Network and Information Security Directive (NIS2) or Critical Entities Resilience (CER)

- Funding schemes for disaster preparedness and infrastructure audits

In Europe, for example, IXPs could be formally recognized within cross-border infrastructure initiatives such as the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF Digital), or monitored through the EU Agency for Cybersecurity’s (ENISA’s) Critical Information Infrastructure Protection (CIIP) strategies.

Europe’s IXP ecosystem is both dense and decentralized. This offers resilience as there’s no single point of failure but also creates coordination challenges. To strengthen this system, we propose:

- A European IXP Resilience Observatory involving RIPE NCC, Euro-IX, ENISA, and IXP operators

- A shared incident response framework for disruptions targeting IXPs

- Optional audits and federated monitoring of Route Server practices

This approach isn’t about replacing existing governance — it’s about reinforcing it, just as IXPs reinforce the Internet itself.

Other regions have different structural realities, but the principle still applies: Resilient Internet infrastructure depends on recognizing IXPs as critical, coordinated assets.

Final thoughts

IXPs are not ‘just switches’. They are interconnection common ground, supporting not only traffic but the values of the Internet itself: Openness, decentralization, and collaboration. Recognizing IXPs as critical infrastructure is not just a symbolic gesture, it is a technical necessity. Treating IXPs as systemic stabilizers means investing in their resilience, governance, and neutrality.

From the local network that keeps a small town online during a blackout, to the continent-wide coordination that buffers entire regions from geopolitical shocks, IXPs are quiet guarantees of continuity. Their impact is visible every time packets stay local instead of traversing oceans, every time a crisis is absorbed instead of amplified.

Future-proofing the Internet demands that IXPs are embedded in resilience strategies, supported by transparent governance, and integrated into regional digital sovereignty efforts. This includes regulatory recognition, funding for redundancy, and cross-border collaboration frameworks. At a time when connectivity is critical to every aspect of society, overlooking IXPs means leaving a blind spot in our collective defences.

A resilient Internet is not possible without resilient IXPs. The path forward is not to centralize more traffic in fewer places, but to build diverse, neutral, and well-governed interconnection points that reflect the same decentralization that made the Internet succeed in the first place.

Flavio Luciani is Chief Technology Officer at Namex (Roma IXP) and co-author of the book ‘BGP: from theory to practice‘.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.