Job Snijders co-authored this post.

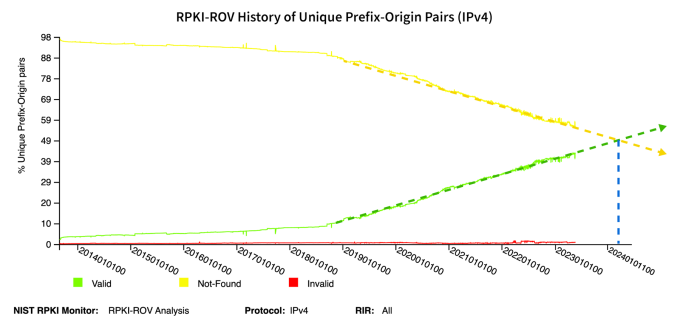

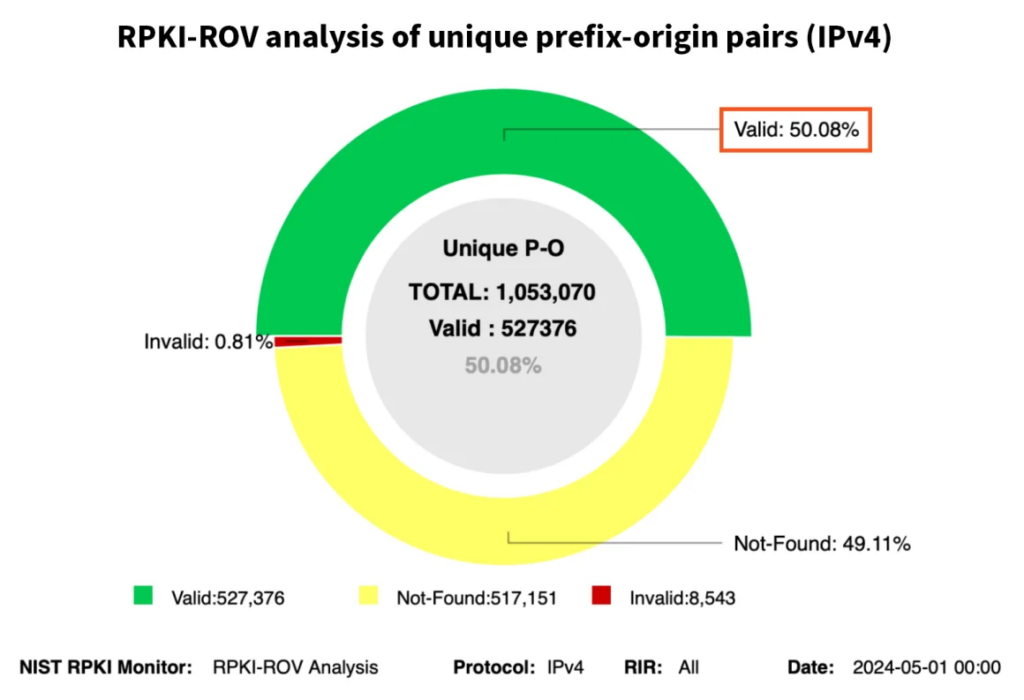

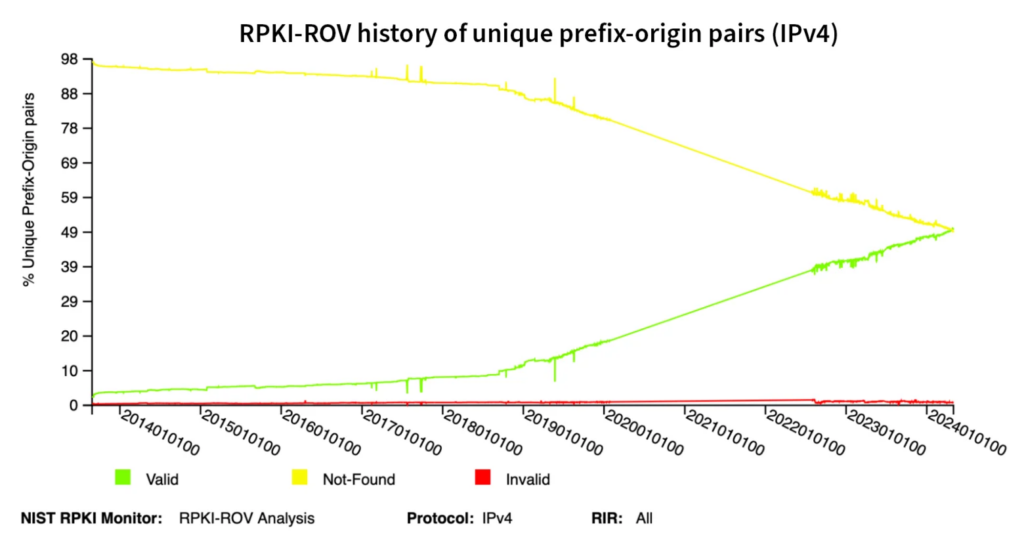

As of 1 May 2024, Internet routing security passed an important milestone. For the first time in the history of RPKI (Resource Public Key Infrastructure), the majority of IPv4 routes in the global routing table are covered by Route Origin Authorizations (ROAs), according to the NIST RPKI Monitor. IPv6 crossed this milestone late last year.

In light of this milestone, let’s take the opportunity to update the figures for RPKI Route Origin Validation (ROV) adoption we’ve been publishing in recent years.

As you may already know, RPKI ROV continues to be the best defence against accidental BGP hijacks and origination leaks. For ROV to do its job (rejecting RPKI invalid routes), two steps must be taken:

- ROAs must be created.

- Autonomous Systems (ASes) must reject routes that aren’t consistent with the ROAs.

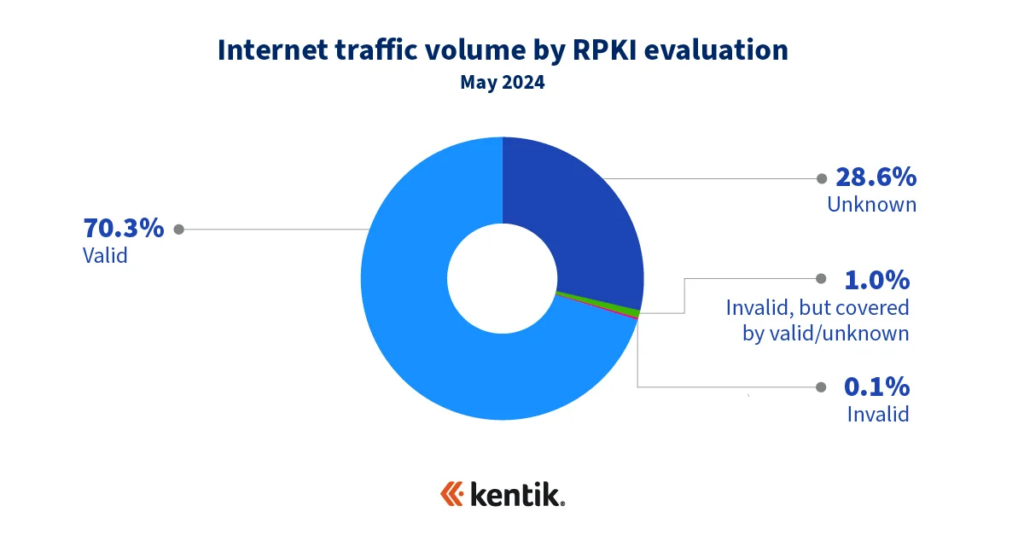

The first part of this analysis began when we explored the first step of ROV: ROA creation. Two years ago at NANOG 84, Doug presented his analysis, which showed that we were, in fact, further along in ROA creation than could be ascertained by analysing BGP alone. Utilizing Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow, he showed that the majority of traffic (measured in bits/sec) was heading to routes with ROAs, despite only one-third of BGP routes having ROAs.

This discrepancy was because major content providers and eyeball networks had completed RPKI deployments in recent years and account for a disproportionate share of Internet traffic volume. Of course, traffic volume isn’t the only criterion for achievement — there is plenty of traffic that is critical, but not voluminous (for example, DNS). The idea was to simply provide another dimension to consider our progress in deploying RPKI ROV.

To measure the second step of ROV (rejection of invalids), we looked at the differences in propagation based on a route’s RPKI evaluation. The conclusion at the time was that invalid routes could achieve a propagation no greater than 50% of the BGP sources in RouteViews, the public BGP repository from University of Oregon, now managed by the Network Startup Resource Center. Oftentimes invalids are propagated far less than 50% — it all depends on the upstreams involved.

The dramatic reduction in the propagation of RPKI invalid routes can be primarily attributed to the Tier-1 backbone providers that reject invalids. These providers cast a long shadow with their outsized influence on Internet routing. Regardless, the reduction in propagation is RPKI ROV doing its thing — suppressing problematic routes so they don’t cause disruption.

ROA creation update

As mentioned above, over 50% of IPv4 routes in the global routing table now have ROAs and are evaluated as valid (with IPv6 at 52%). Let’s check what that means for Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow.

According to our analysis two years ago, we had roughly one-third of routes with ROAs and just over 50% of Internet traffic as ‘valid’ (traffic to routes evaluated as valid in bits/sec). Now with over half of IPv4 routes with ROAs, our current aggregate NetFlow reveals a whopping 70.3% of Internet traffic being valid!

How much higher can this metric go? It remains to be seen. As depicted below in another NIST diagram, the upward slope of the percentage of routes with ROAs has held remarkably steady for the past four years. It stands to reason we will eventually see the slope flatten out as the number of easy wins begins to dwindle. However, it is important to recognize the progress made to date.

Invalid route propagation update

The aforementioned progress in the creation of ROAs is useless if networks are not rejecting RPKI invalid BGP routes. So, the next step in understanding where we are at with RPKI ROV adoption is to better understand the degree to which the Internet rejects RPKI invalid routes.

Among the Internet’s largest transit providers (transit-free), all but a couple were rejecting RPKI invalid routes when we published our post, How much does RPKI ROV reduce the propagation of invalid routes? As a result, we concluded that “the evaluation of a route as invalid reduces its propagation by anywhere between one-half to two-thirds.”

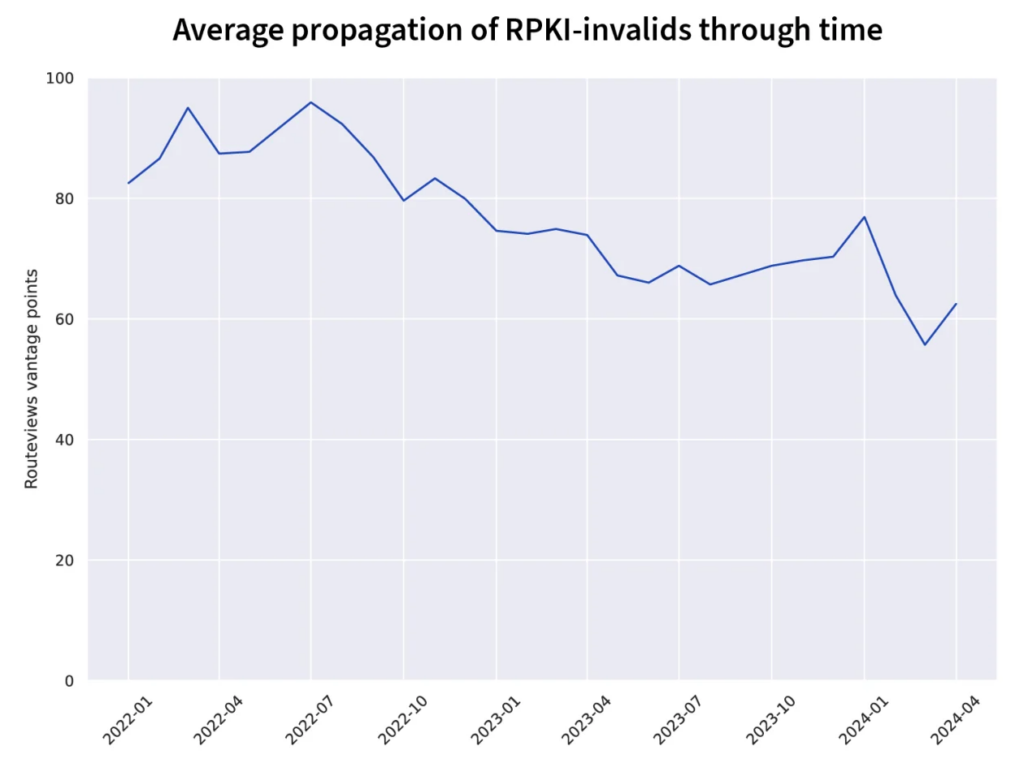

Now, two years later, we can explore how this metric has evolved over this period of time. Using historical RPKI data made available via Job’s RPKIviews site and BGP routing data from RouteViews, we evaluated the IPv4 global routing table every month going back to the beginning of 2022 to determine how the propagation of RPKI invalid routes has changed over time.

Recall that in this methodology, we measure the propagation of a route by counting how many RouteViews vantage points have the route in their tables. More vantage points mean greater propagation. For more explanation on this approach, see our invalid route propagation analysis.

Figure 4 shows the average number of RouteViews vantage points for each RPKI invalid route over time. We only include routes seen by at least 10 vantage points to avoid internal routes shared with RouteViews vantage points. At the beginning of the plot, we identified 4,978 RPKI invalid routes that were seen, on average, by 82.5 vantage points. In the last data point from 1 April 2024, we observe 4,211 RPKI invalid routes seen by 62.5 vantage points.

Note: We used a well-known globally routed prefix (Google’s 8.8.8.0/24) as a control prefix for the effects of temporary changes in the count of RouteViews vantage points.

The main challenge to this type of analysis is that it is quite noisy. The set of persistently RPKI invalid routes does not stay constant and propagation is heavily influenced by which providers are transiting a route. Those challenges aside, the analysis above shows a 24% decline in the propagation of RPKI invalid routes since the beginning of 2022.

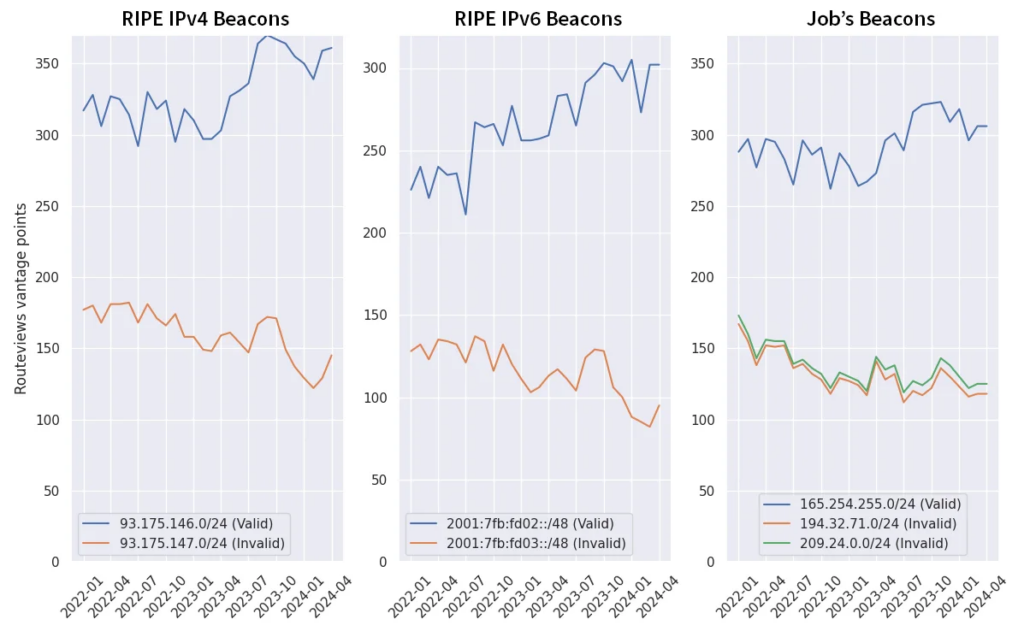

To explore this phenomenon further, we can take a look at the routing of intentionally RPKI invalid routes over time and see that they also experience a similar decline in propagation.

RIPE NCC announces numerous ‘Routing Beacons‘ for measurement purposes. Among these are routes that are intentionally RPKI invalid (and RPKI valid for a control). Not to be outdone, Job also announces RPKI invalid routes along with a control route from his network, AS15562.

Below is a graphic displaying the RouteViews vantage point count for each of these measurement routes over time. The plots corresponding to the RPKI invalid routes appear in the lower portion of the graphs, in keeping with our observation that RPKI invalid routes propagate significantly less.

The three plots in this graphic all show a noticeable decline in the number of vantage points observing the various RPKI invalid routes. This decline matches the drop in the average number of vantage points observing any given RPKI route from earlier.

There is one final observation to make based on this analysis. In the panel on the right (‘Job’s Beacons’), there are two RPKI invalid routes with slightly differing degrees of propagation.

209.24.0.0/24 (green) has its ROA published via the ARIN Trust Anchor Locator (TAL), while 194.32.71.0/24’s (orange) is reachable via the RIPE TAL. A TAL is a file with a public key used by Relying Parties to retrieve RPKI data from a repository.

The likely issue is that using the ARIN TAL requires agreeing to a lengthy Relying Party Agreement, which some providers refuse to do. As a result, ROAs published by ARIN are seen by slightly fewer networks that reject RPKI invalid routes, decreasing the efficacy of RPKI for ARIN-managed IP space.

ARIN’s strong indemnification clause comes from their worry about being sued due to something that happens as a result of the data they publish in the RPKI. This obstacle to RPKI ROV adoption was covered in a 2019 academic article, ‘Lowering Legal Barriers to RPKI Adoption‘ by professors Christopher S. Yoo and David A. Wishnick of the University of Pennsylvania.

But alas, let’s get back to the progress we’re seeing in the rejection of RPKI invalids.

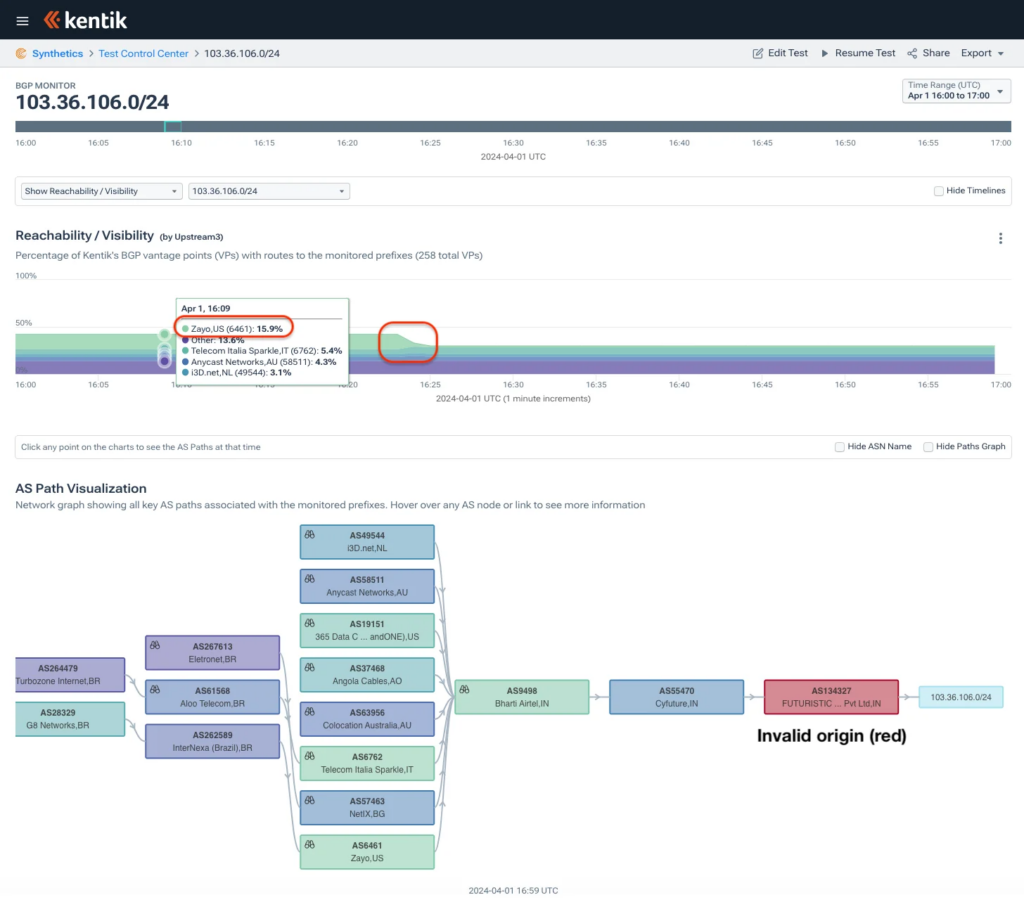

At the beginning of this section, we mentioned how all but two transit-free providers were rejecting RPKI invalid routes. Well, the other milestone that occurred this past month is that that number dropped to just one as US telecom operator Zayo (AS6461) began rejecting RPKI invalid routes from its customers.

In 2022, Zayo announced that it had begun rejecting RPKI invalids from its settlement-free peers. However, since nearly all of its big peers were already rejecting those routes, the impact was relatively minor.

But on 1 April, we began seeing AS6461 begin rejecting RPKI invalids from customers for the first time. In the Kentik visualization shown in Figure 6, RPKI invalid route 103.36.106.0/24 stopped being transited by AS6461 at 16:24 UTC.

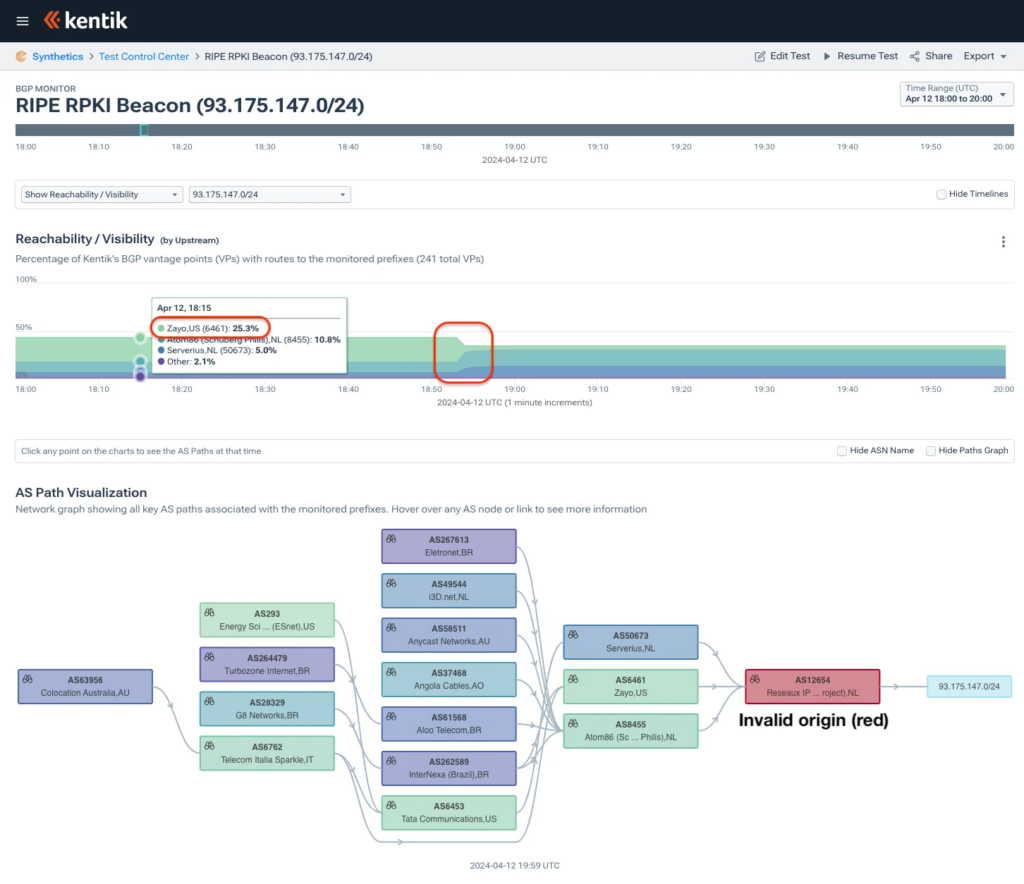

The rollout of Zayo’s rejection of RPKI invalids was done in phases and a couple of weeks later we started seeing other parts of their global network rejecting RPKI invalids. At 18:54 UTC on 12 April, we observed AS6461 begin rejecting RIPE’s RPKI invalid beacons, 93.175.147.0/24 and 2001:7fb:fd03::/48, for the first time.

Once completed, we expect Zayo’s rejection of RPKI invalid routes from its customer base to continue to lower the propagation of these problematic routes reducing the risk of traffic disruption or misdirection due to many types of routing mishaps.

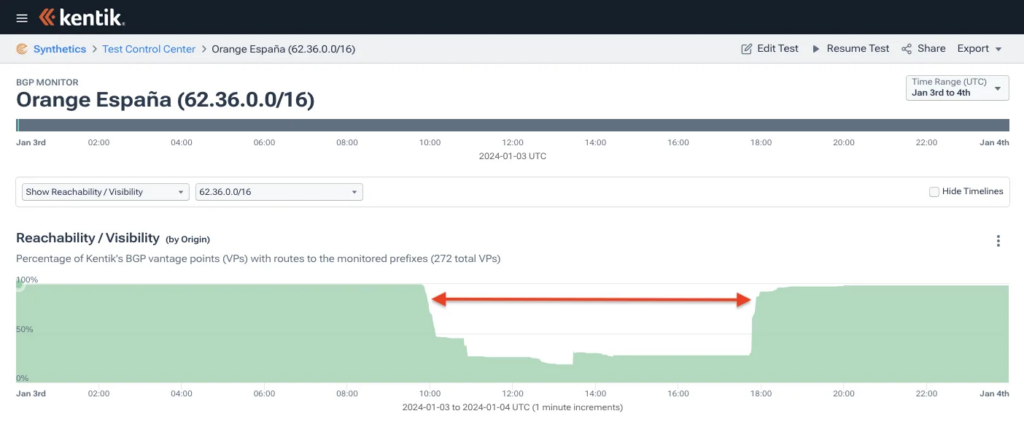

And finally, for anyone still sceptical about the degree to which invalid routes are being rejected, may we direct your attention to the Orange España outage in January. I summarized the incident in a blog post published the day after the hack.

Using a password found in a public leak of stolen credentials, a hacker was able to log into Orange España’s RIPE NCC portal using the password ‘ripeadmin’. Oops! Once in, this individual began altering Orange España’s RPKI configuration, rendering many of its BGP routes RPKI-invalid

Digging into the Orange España Hack

The wielding of RPKI as a tool for denial of service was only possible due to the pervasive extent to which ASNs reject RPKI invalid routes.

Conclusion: Benefits of deploying RPKI

In our blog post from one year ago, we made the following bold prediction:

If we are to assume steady growth of the share of BGP routes with ROAs, it should become the majority case in about a year from now (May 2024). Mark your calendars!

Exploring the Latest RPKI ROV Adoption Numbers, 24 May 2023.

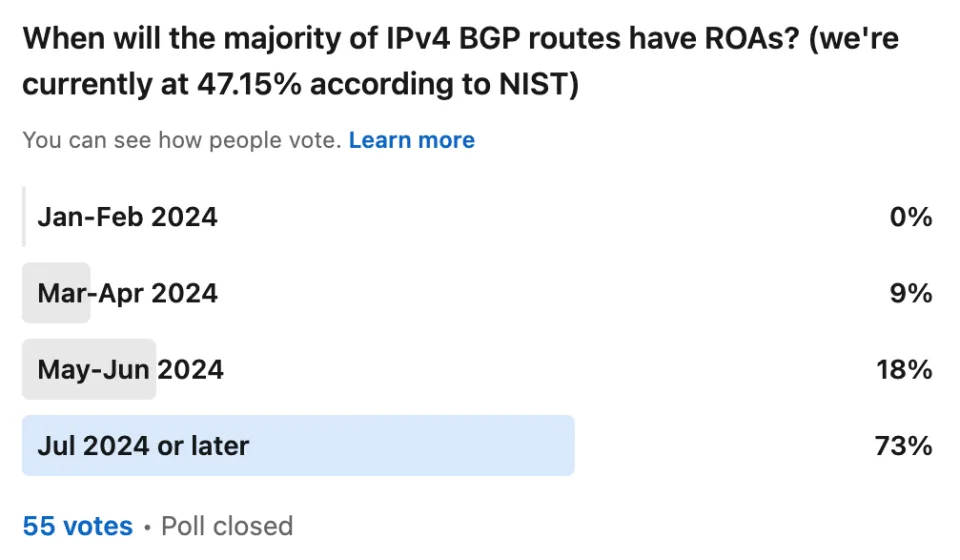

In December, we polled fellow BGP nerds on Twitter/X and LinkedIn when respondents believed we would hit this mark and they were decidedly more pessimistic than the prediction above:

The progress detailed in this blog post was years in the making and involved the dedicated efforts of hundreds of engineers at dozens of companies. Improving the security of the global Internet routing system is not a small task and will continue to be a years-long effort.

Each of the two lines of analysis from this post should serve as motivation for additional networks to deploy RPKI ROV.

- Reject RPKI invalid BGP routes on eBGP sessions. Given that the majority of Internet routes are covered by ROAs (including a supermajority of traffic), network operators should reject RPKI invalid routes to avoid mistakenly egressing customer traffic towards mis-originated routes.

- Create ROAs. And given the scale to which RPKI invalid routes are suppressed, it would benefit resource holders to create ROAs for their address ranges to enable networks around the world to automatically reject mis-originated routes.

Networks that do so enjoy immediate benefits!

But RPKI ROV doesn’t solve all of the issues surrounding Internet routing security. In fact, this is only an opening salvo towards addressing the various ‘determined adversary’ scenarios best characterized by the recent attacks against cryptocurrency services. These attacks take advantage of existing weaknesses in Internet security that we will need to work to limit by building off the progress made by routing security mechanisms like RPKI ROV.

Doug Madory is the Director of Internet Analysis for Kentik where he works on Internet infrastructure analysis.

Job Snijders (Twitter, Mastodon, homepage) is a Principal Engineer at Fastly where he analyses and architects global networks for future growth, and also an OpenBSD developer.

Originally posted Kentik Blog.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.