Distributed Denial-of-Service- (DDoS-) for-hire systems are commonly known as ‘booters’ or ‘stressers’ in the Internet underground and security community. The term ‘booter’ derives from a common use-case for these services: To ‘boot’ a player out of a game by disrupting their connection, presumably allowing a competitive, attacking player to gain an advantage or deflate a target player’s ranking.

A ‘stresser’ is a term favoured by DDoS-for-hire operators, which might suggest an air of legitimacy, as if the use-case is only to ‘stress test’ a target network that has agreed to receive DDoS attack traffic. DDoS-for-hire operators even put language into their service description that claims a user of the service is solely responsible for any damages that result from the service. Unfortunately for those operators, most jurisdictions disagree.

Not only is operating these services generally illegal, so is using them. In other words, all parties across the globe that are involved in setting up, coordinating, operating, purchasing, and using these services put themselves in legal jeopardy and risk serious criminal liability.

The takedown

On December 15, 2022, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), in cooperation with several international law enforcement partners, seized 49 domain names and arrested six individuals for their alleged involvement in the operation of illegal DDoS-for-hire activity.

The coordinated seizure led by the FBI in December is colloquially known as a ‘takedown’ event, but it might be best thought of as a ‘disruption’. While the seizures affected approximately 50% of the most active DDoS-for-hire services on the Internet, many of them reconstituted operations using new domain names, albeit (as Dr Clayton shows in his NANOG presentation) the frequency of attacks sourced from these services was significantly reduced or disrupted.

The number of DDoS attacks these sites were responsible for was staggering. Many facilitated hundreds of attacks per day, while the largest averaged thousands of attacks per day! Many of the DDoS-for-hire services publish attack capabilities and statistics. Not only were security researchers involved in the takedown able to validate actual attack volume with these reported statistics, but one only needs to look at NETSCOUT’s global attack statistics to realize the claims of the attack statistics on DDoS-for-hire sites are an accurate reflection of reality.

Network effects after takedown

NETSCOUT researchers’ part in the takedown assessment was to examine what, if any, measurable effect in DDoS attack activity resulted from the December 15, 2022 takedown event. Our ATLAS platform provides insight into attack alerts as seen by networks around the globe. This DDoS attack telemetry spans the globe and allows unparalleled insight into real-time DDoS activity. We analyzed our attack data to see if we could identify any takedown cause and effect.

DDoS-for-hire operators advertise a variety of attack types that can be carried out by their platform. This includes application-layer attacks, such as HTTP request floods, TCP state exhaustion attacks such as SYN floods, and amplification/reflection style attacks using common UDP request/response protocols such as DNS, Network Time Protocol (NTP), and Connectionless Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (CLDAP).

On and around 15 December 2022, we examined if any difference in total TCP and UDP attack traffic occurred. This proved too wide of a lens from which to draw any definitive conclusions given the vast quantities of DDoS-for-hire services, botnets, and attack tools always present in our data. Instead, we focused our attention on specific networks and attack vector types.

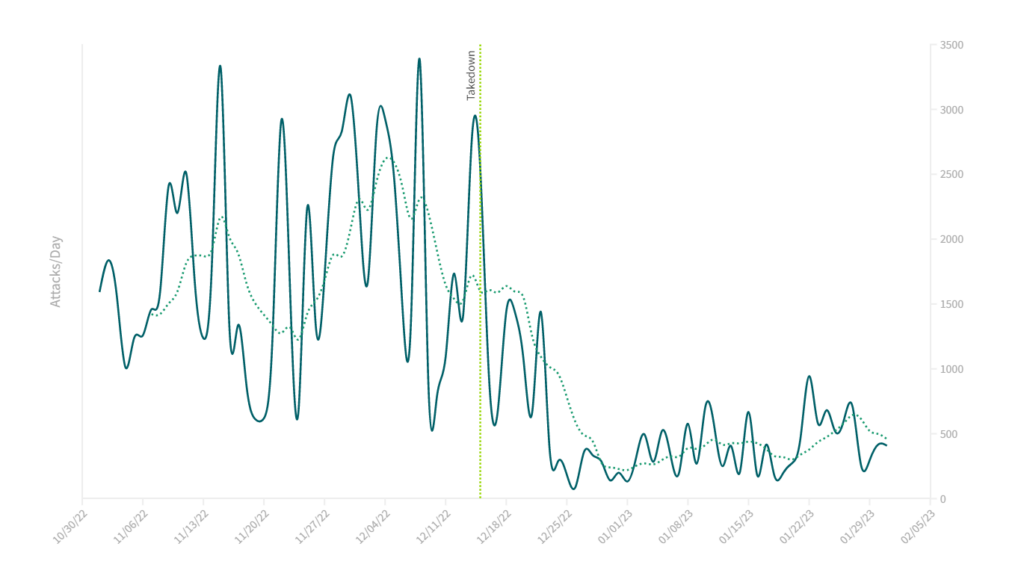

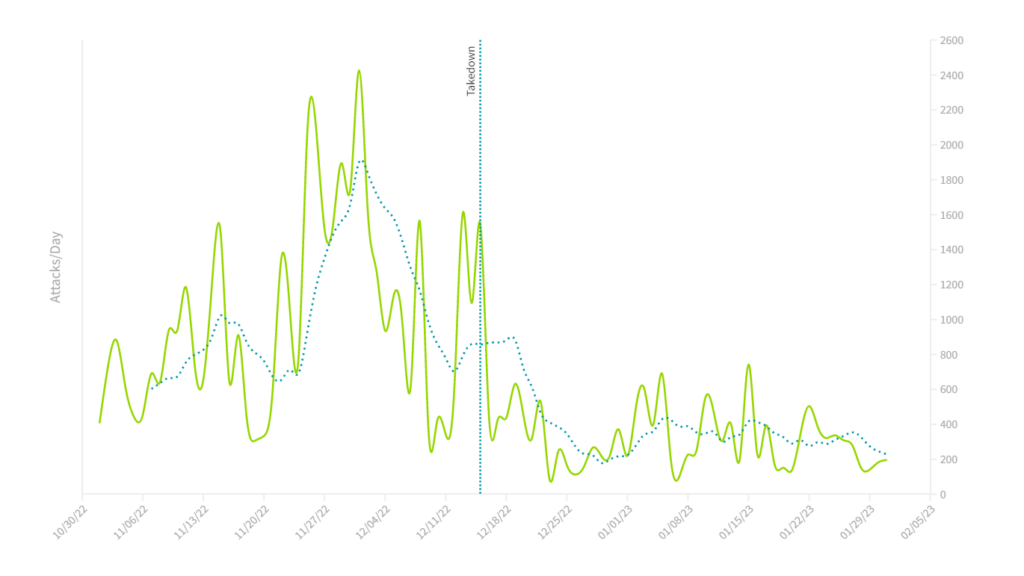

Knowing that many users of DDoS-for-hire services target gamers or gaming servers, we homed in on one large US broadband provider (Figure 2) and one large European server hosting provider (Figure 3). From these two plots, it appears as if the takedown event corresponds almost perfectly with a visible, sudden drop in attacks towards these networks.

Not only was there a precipitous drop in traffic in both cases on or around December, but the overall attack volume remained, on average, significantly reduced through the end of January 2023. This seemed to suggest a direct correlation between the takedown event and observed DDoS attack traffic.

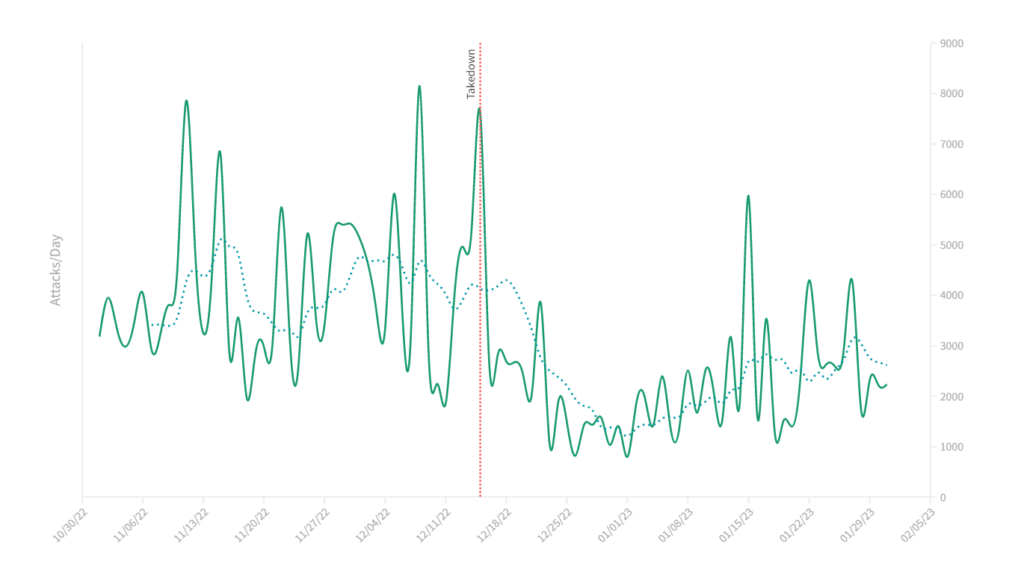

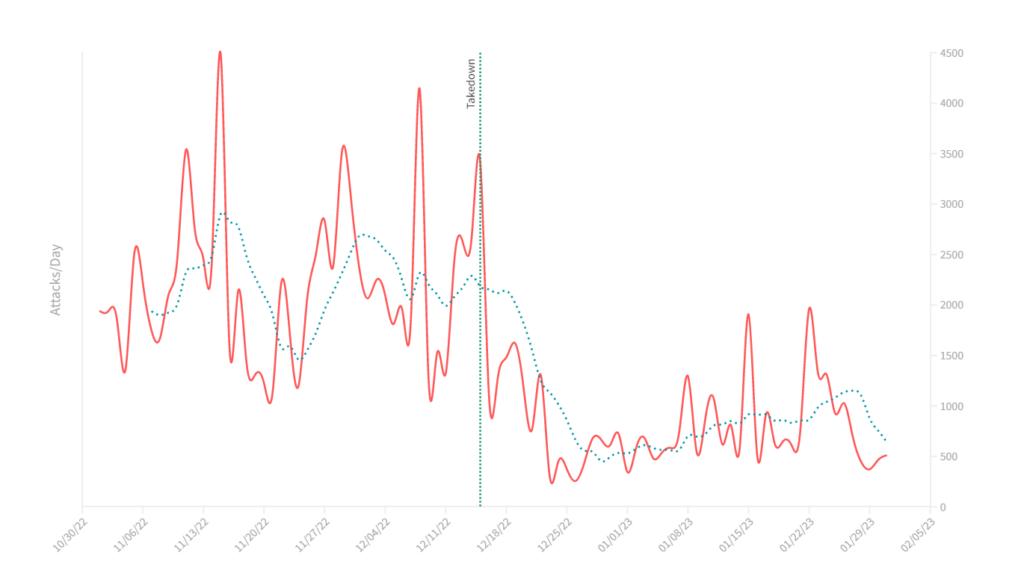

Similarly, when we considered specific attack vectors such as DNS (Figure 4) and NTP amplification/reflection (Figure 5) attacks, we saw similar patterns.

We were tempted to declare incontrovertible evidence of a correlation between the takedown and global DDoS attack traffic, but then we examined how these attack trends compared with the same period one year earlier. Here is where our conclusions must be tempered by declaring there was a ‘probable’ decrease in global DDoS attack numbers.

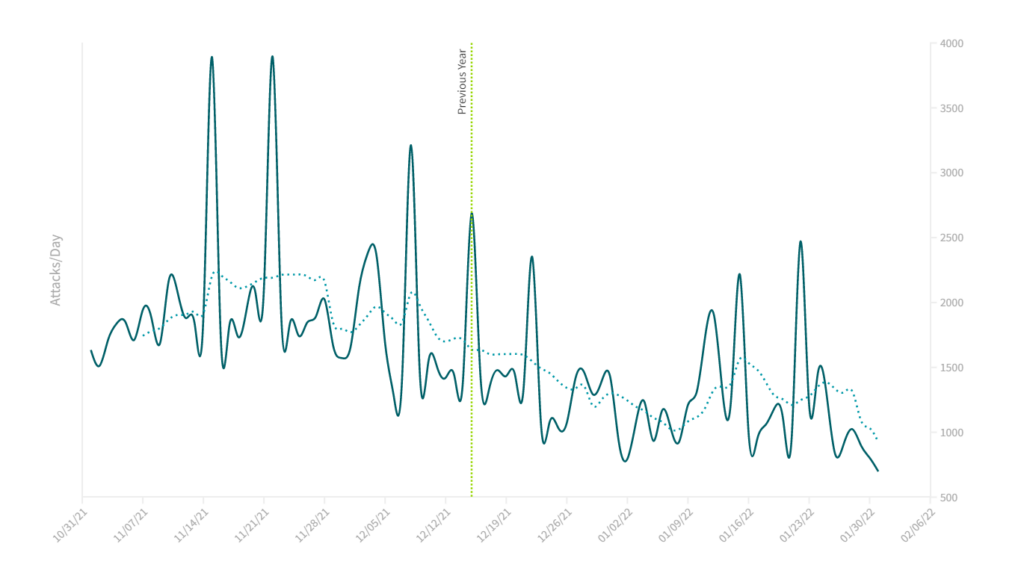

Due to the breadth and coverage of our attack data, all other DDoS attacks that continued uninterrupted make the 15 December 2022 graphs look a little underwhelming. We compared the shape of the NTP attacks plot from 2022 to 2023 (Figure 5) with the NTP attacks plot from 2021 to 2022 (Figure 6).

The shape and trend of attacks during the same interval are clearly different in the most recent period to that of a year earlier. In the 15 December 2023 time frame, the change in attack volume is sudden and dramatic. In the year earlier, there is a more gradual decrease in attack volume, with no single inflection point.

What we find when we compare attack trends between the two years is that there is a corresponding decrease in attacks that coincide with seasonal trends, a trend that tracks back many years.

These end-of-year seasonal trends appear to mask, at least somewhat, the effect of the takedown event in December 2022. Nonetheless, on average the number of NTP attacks is 40% lower after 15 December than the equivalent period before the takedown. The trend is similar for other specific and common DDoS-for-hire targets and attack vectors.

Conclusion

The primary aim of the December takedown event was DDoS-for-hire service disruption. Disruption is like cutting off several heads on a hydra. There’s temporary relief, but inevitably, the adversary regains their ability to launch attacks. However, this is just one form of mitigating DDoS attacks.

These takedowns also act as a deterrent to DDoS service operators and users. Arrests and threats of legal action are other deterrents that continue to be used in conjunction with all the technical tools at our disposal. Though the takedown wasn’t as impactful as hoped, the joint effort from security research and law enforcement is just one of many paths to solving the world’s DDoS problem.

Note: This article is a companion piece to the recent NANOG 87 talk Assessing the Aftermath: Evaluating the effects of a global DDoS-for-hire service takedown given by Dr Richard Clayton of the University of Cambridge, and NETSCOUT ASERT principal analyst, John Kristoff.

John Kristoff (Mastodon) is a PhD candidate in Computer Science at the University of Illinois Chicago studying under the tutelage of Chris Kanich. He is a principal analyst at NETSCOUT on the ATLAS Security Engineering and Response Team (ASERT). John is also adjunct faculty in the College of Computing and Digital Media at DePaul University. He currently serves as a research fellow at ICANN, sits on the NANOG program committee, and operates Dataplane.org.

Adapted from the original post on the NETSCOUT blog.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.