A router is a gateway from the Internet to a home or office — despite being conceived as quite the opposite. Routers are forever being hacked and infected, and used to infiltrate local networks. Keeping this gate locked so that no one can stroll right through is no easy task. It is not always clear just how this locking works, especially when it comes to home routers, whose users are by no means all security pros. What’s more, it’s not uncommon for routers to be full of holes.

Read: A brief history of router architecture

Since the start of the pandemic, however, router security has received more attention. Many companies introduced remote working for employees, some of whom never returned to the office. If before the pandemic few people worked from home, now their number is significant. As a result, cybercriminals now see home routers as gateways to corporate networks, and companies as potential attack vectors. Proof of the heightened attention in network devices comes from the sharp rise in the number of vulnerabilities found in them in recent years.

Router vulnerabilities

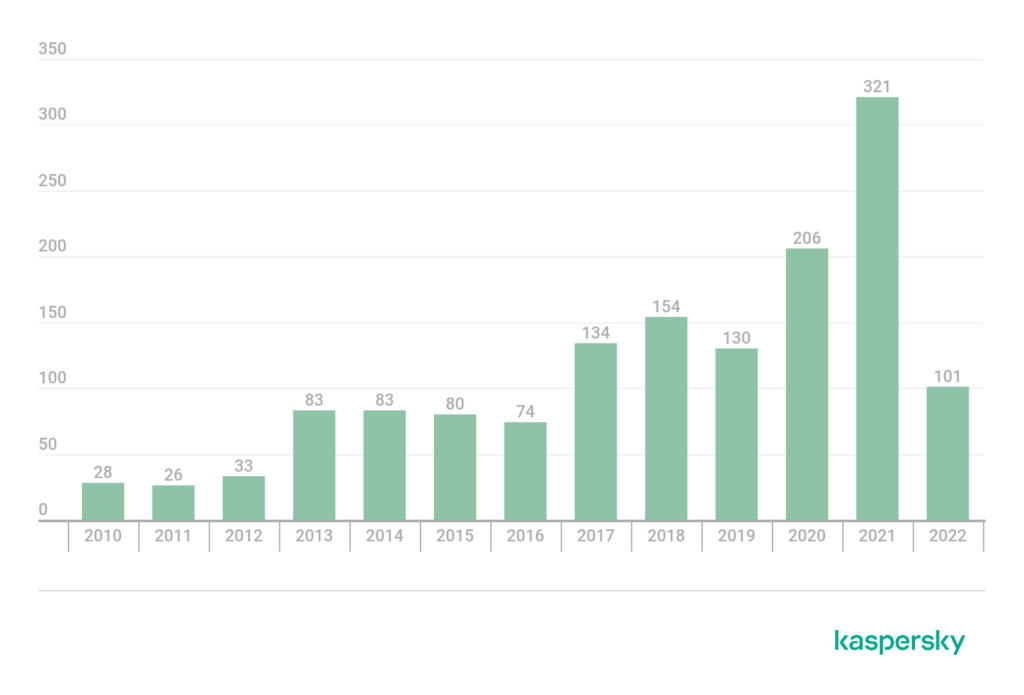

According to cve.mitre.org, the number of vulnerabilities discovered in various routers, from mobile to industrial, has grown over the past decade. However, with the mass shift to remote working, it went off the scale. During 2020 and 2021, more than 500 router vulnerabilities were found.

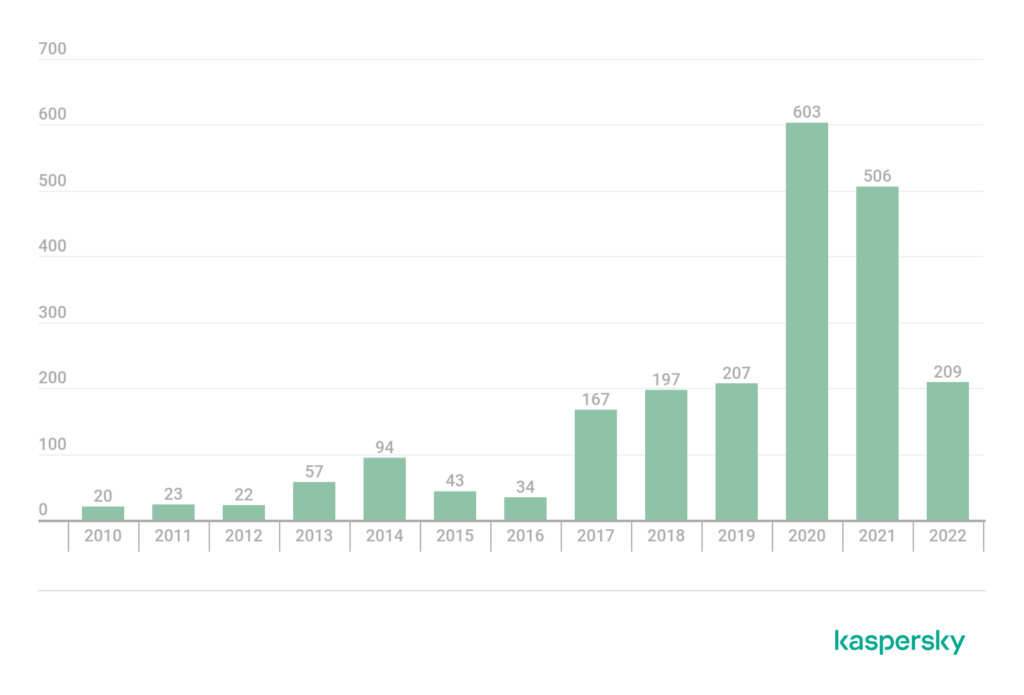

The nvd.nist.gov website presents different figures, but they too show a significant increase in the number of router vulnerabilities found in 2020 and 2021.

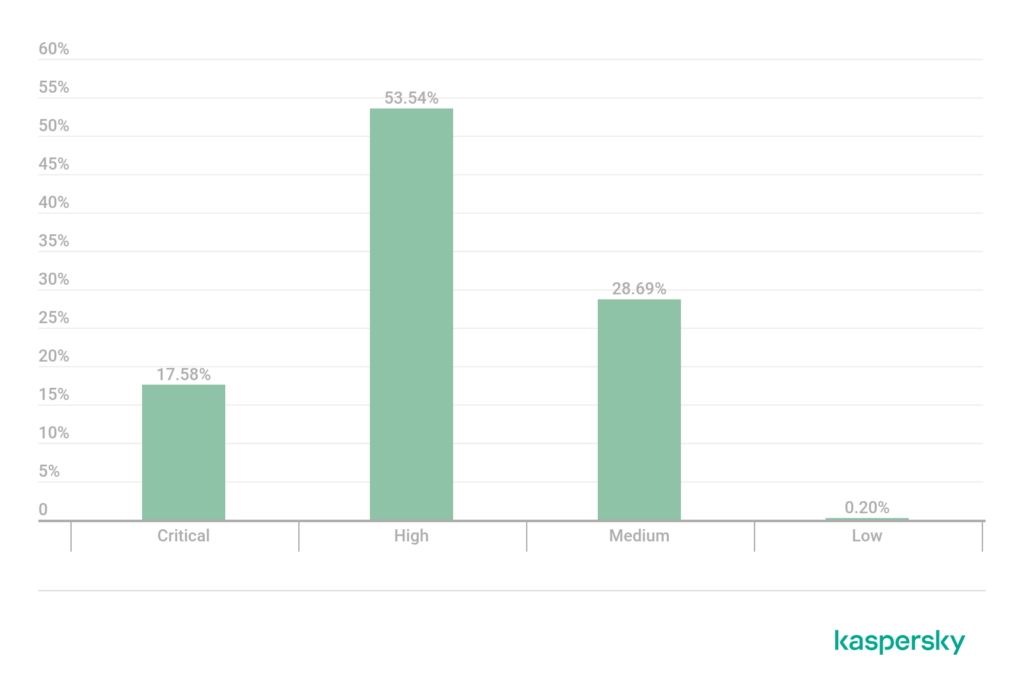

Analysing the nvd.nist.gov data on router vulnerabilities, we calculated that 18% were critical, and more than half (53.5%) were high priority.

Critical vulnerabilities are the very holes in the gateway through which an intruder can penetrate a home or corporate network. They make the router much easier to hack, which gives the opportunity to get round password protection features (such as CAPTCHA or a limited number of login attempts), run third-party code, bypass authentication, send remote commands to the router or even disable it. In early 2022, for instance, a security researcher effectively cut off the whole of North Korea from the Internet by exploiting unpatched vulnerabilities in critical routers and other network equipment.

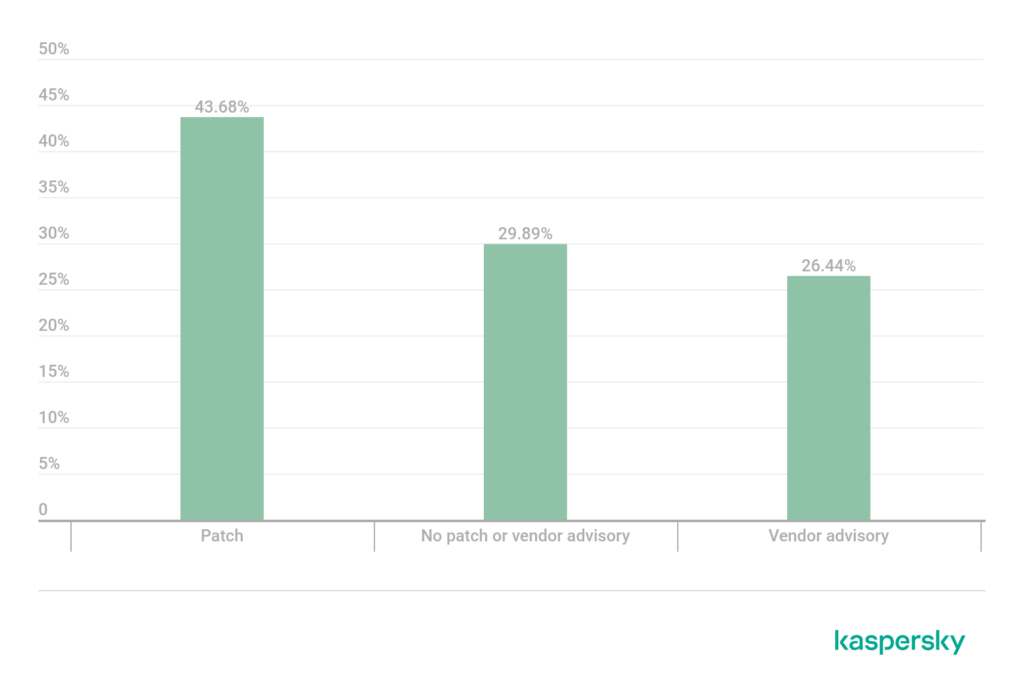

Unfortunately, not all vendors are rushing to fix even critical vulnerabilities. At the time of writing, of the 87 critical vulnerabilities published in 2021, more than a quarter (29.9%) remain unpatched and unreported by the vendor:

Note the third column in Figure 4: 26% of all critical router vulnerabilities published in 2021 received a vendor advisory. These advisories do not always come with a full-fledged patch. In some cases, they only recommend owners of vulnerable devices to contact support.

Moreover, whereas employees have more or less got to grips with protecting laptops, desktop computers and even mobile devices, they may not know what to do, if anything, with routers. According to a survey by UK company Broadband Genie, 48% of users had not changed any of their router’s settings at all, even the control panel and WiFi network passwords. 73% of them just see no reason to go into the settings, and 20% do not know how to do it.

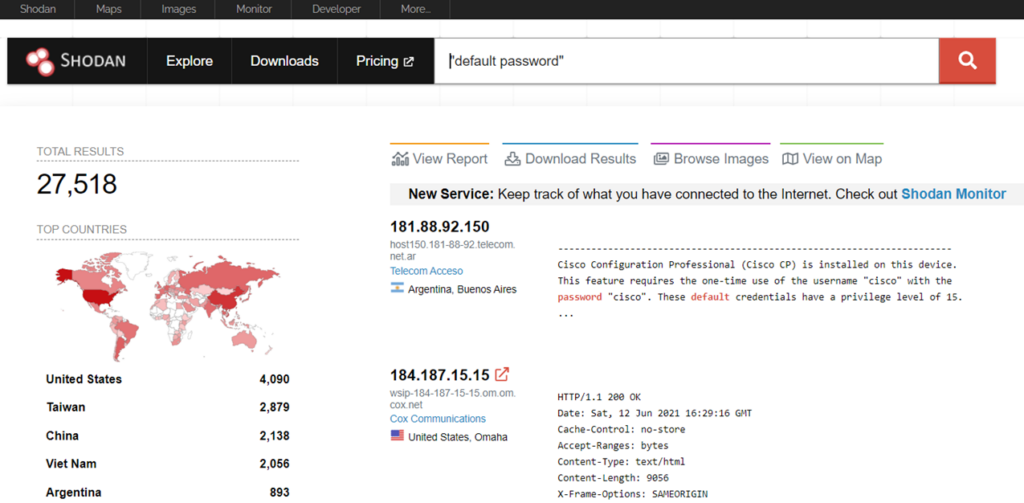

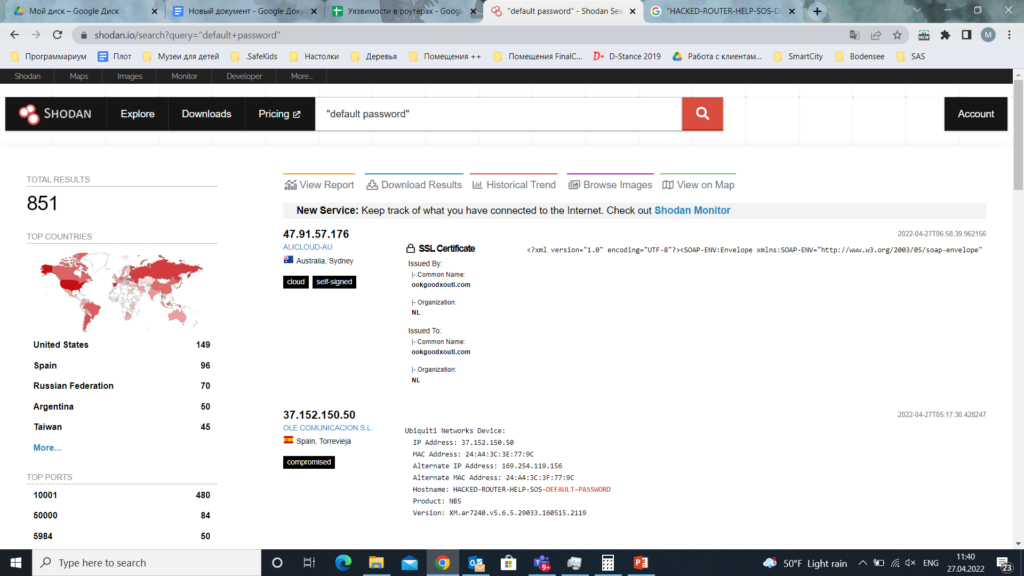

That said, the situation with router security is gradually improving. If a Shodan.io search for smart devices with the default password in the summer of last year revealed more than 27,000 hits, a similar search in April 2022 returned only 851. Moreover, most of these routers had the name HACKED-ROUTER-HELP-SOS-DEFAULT-PASSWORD, indicating they had already been compromised.

These results are most likely due to the fact that many vendors started creating unique, random passwords for each individual device, instead of a standard default password for all of them, available to anyone.

Router-targeting malware

To find out why cybercriminals attack routers, it is first worth looking at the Top 10 malware detected by our IoT traps in 2021.

| Verdict | Attack % | |

| 1 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.b | 48.25 |

| 2 | Trojan-Downloader.Linux.NyaDrop.b | 13.57 |

| 3 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ba | 6.54 |

| 4 | Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.a | 5.51 |

| 5 | Backdoor.Linux.Agent.bc | 4.48 |

| 6 | Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.p | 2.54 |

| 7 | Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.bj | 1.85 |

| 8 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.a | 1.81 |

| 9 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.cw | 1.51 |

| 10 | Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.bc | 1.36 |

As the table shows, around a half of all verdicts belong to the Mirai family. Discovered back in 2016, it remains the most common malware infecting IoT devices. This botnet of routers, smart cameras, and other connected devices is the most persistent, since infected devices cannot be cured by any protective technologies, and users often do not notice that something is wrong.

The Mirai botnet was originally designed for large-scale DDoS attacks on Minecraft servers, and was later employed to attack other resources. After its source code was published, all and sundry began to distribute it and conduct DDoS attacks using Mirai-infected devices.

Read: Your questions answered about Mirai Botnet

Read: Preparing for the next large-scale IoT botnet attack

Mirai is not the only DDoS malware to target routers. In September 2021, the Russian companies Yandex, Sber, and others were subjected to the largest DDoS attack ever observed using a new botnet of MikroTik routers. Researchers named the botnet Meris. It is believed to consist of 200 to 250 thousand devices infected with the new malware.

Thus, one of the main goals of attacking routers is to recruit them into botnets to carry out large-scale DDoS attacks.

But we should not forget the main function of a router — to act as a gateway to the Internet from a local network. Cybercriminals can hack into routers to get into a user’s or company’s network. Such attacks can be smaller in scale than creating DDoS botnets, for which reason they are not listed in the most common threats to routers. That said, they are far more dangerous for companies than Mirai.

For example, there have been reports about attacks by the Sandworm APT group on small office/home office (SOHO) network devices. The cybercriminals infected WatchGuard and Asus devices with the Cyclops Blink malware. Although we cannot say for sure what they intended to do next, this malware persists in the firmware even after a factory reset and gives attackers remote access to compromised networks.

Recommendations to secure your home router/develop security guidelines

The growing interest in router security in recent years stems largely from the belief that protecting a router is a task beyond the grasp of ordinary users. At the same time, remote working allows intruders to penetrate a company’s infrastructure by exploiting a security hole in an employee’s home network. It’s a mouth-watering prospect for attackers, but companies are not blind to the threat.

If you want to secure your home router or develop security guidelines for remote employees, we advise the following:

- Change the default password to one that is strong (that is, long and complex). There is no shame in writing down the password for your home router — it is rarely used and physical access to the router is restricted to a small circle of individuals.

- Use proper encryption. As of today, that means WPA2.

- Disable remote access. To do so, simply find this setting in the interface and uncheck Remote Access. If remote access is needed after all, disable it when not in use.

- Make sure to update the firmware. Before purchasing a router, make sure that the vendor issues firmware updates on the regular basis and install them promptly on the device.

- For extra security, use a static IP address and turn off DHCP, as well as protect Wi-Fi with MAC filtering. All this will make the process longer and more complicated, as you will need to set up any additional device connections manually. But it will be far harder for an intruder to get into the local network.

This post is adapted from the original at Secure List.

Maria Namestnikova is the Head of Global Research & Analysis Team, Russia, for Kaspersky.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Good