It has become either a tradition, or a habit, each January for me to report on the experience with the inter-domain routing system over the past year; looking in some detail at some metrics from the routing system that can show the essential shape and behaviour of the underlying interconnection fabric of the Internet.

One reason why we are interested in the behaviour of the routing system is that at its heart the system has no natural limitation. Our collective unease about routing relates to a potential scenario where every network decides to deaggregate their prefixes and announce only the most specific prefixes. Or where every network applies routing configurations that are inherently unstable and the routing system rapidly reverts into oscillating states that generate an overwhelming stream of routing updates into the BGP realm.

In such scenarios, the routing protocol we use, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) will not help us by attempting to damp down the anomalies. Indeed, there is a very real prospect that in such scenarios the protocol behaviour of BGP could well amplify the behaviour!

BGP is an instance of a Bellman-Ford distance vector routing algorithm. This algorithm allows a collection of connected devices (BGP speakers) to each learn the relative topology of the connecting network.

The basic approach of this algorithm is very simple: each BGP speaker tells all its other neighbours about what it has learned if the new learned information alters the local view of the network. This is a lot like a social rumour network, where every individual who hears a new rumour immediately informs all their friends.

BGP works in a very similar fashion: each time a neighbour informs a BGP speaker about reachability to an IP address prefix, the BGP speaker compares this new reachability information against its stored knowledge that was gained from previous announcements from other neighbours. If this new information provides a better path to the prefix, then the local speaker moves this prefix and associated next hop forwarding decision to the local forwarding table and informs all its immediate neighbours of a new path to a prefix, implicitly citing itself as the next hop.

In addition, there is a withdrawal mechanism, where a BGP speaker determines that it no longer has a viable path to a given prefix, in which case it announces a ‘withdrawal’ to all its neighbours. When a BGP speaker receives a withdrawal, it stores the withdrawal against this neighbour.

If the withdrawn neighbour happened to be the currently preferred next hop for this prefix, then the BGP speaker will examine its per-neighbour data sets to determine which stored announcement represents the best path from those that are still extant. If it can find such an alternative path, it will copy this into its local forwarding table and announce this new preferred path to all its BGP neighbours. If there is no such alternative path, it will announce a withdrawal to its neighbours, indicating that it no longer can reach this prefix.

And that’s BGP.

What could possibly go wrong?

The first is the sheer size of the routing tables. Each router needs to store a local database of all prefixes announced by each routing peer.

In addition, conventional routing design places a complete set of ‘best’ paths into each line card, and performs a lookup into this forwarding data structure for each packet. This may not sound all that challenging until you do some basic calculations and work out that at 100Gbps (which is not uncommon these days) a single such ‘wire’ could present one valid 64 octet IP packet every 5 nanoseconds. Performing a lookup into a data structure of around one million entries for an imprecise match of a 32-bit value within 5 nanoseconds represents an extremely challenging silicon design problem. The larger the search space, the harder the problem!

Secondly, there is the stability of the system. Processing a routing update requires several lookups into local data structures as well as local processing steps. Each router has a finite capacity to process updates, and once the update rate exceeds this local processing capability, the router will start to queue up unprocessed updates. The router will start to lag in real time, so that the information a BGP speaker is propagating reflects a past local topology, not necessarily the current local topology. If this lag continues, at some point updates may be dropped from the queue. BGP has no inherent periodic refresh capability, so when information is dropped the router, and its neighbours fall out of sync with the network topology. At its most benign, the router will advertise ‘ghost’ routes where the prefix is no longer reachable, yet the out-of-sync router will continue to advertise reachability. At its worst, the router will set up a loop condition and as traffic enters the loop it will continue to circulate through the loop until the packet’s TTL expires. This may cause saturation of the underlying transmission system and trigger further outages which, in turn, may add to the routing load.

So, the critical metrics we are interested in are the size of the routing space and its level of update, or ‘churn’.

The BGP measurement environment

In trying to analyze long baseline data series, the ideal approach is to keep as much of the local data gathering environment as stable as possible. In this way, the changes that occur in the collected data reflect changes in the larger environment, as distinct from changes in the local configuration of the data collection equipment.

The measurement point being used is a BGP speaker configured within AS131072. This AS generates no traffic and originates no routes in BGP. It’s a passive measurement point that has been logging all received BGP updates since 2007. The router is fed with a default-free eBGP feed from AS4608, which is the APNIC network located in Australia, and AS4777, which is the APNIC network located in Japan, for both IPv4 and IPv6 routes.

There is also no iBGP component in this measurement setup. While it has been asserted at various times that iBGP is a major contributor to BGP scalability concerns in the BGP, the consideration here in trying to objectively measure this assertion is that there is no “standard” iBGP configuration, and each network has its own rather unique configuration of Route Reflectors and iBGP peers. This makes it hard to generate a ‘typical’ iBGP load profile, let alone analyze the general trends in iBGP update loads over time.

In this study, the scope of attention is limited to a simple eBGP configuration that is likely to be found as a ‘stub’ AS at the edge of the Internet. This AS is not an upstream for any third party, it has no transit role, and does not have a large set of BGP peers. It’s a simple view of the routing world I see when I sit at an edge of the Internet.

The Data

The IPv4 routing table

Measurements of the size of the routing table have been taken on a regular basis since the start of 1988, although detailed snapshots of the routing system only date back to early 1994.

Figure 1 shows a rather unique picture of the size of the routing table as seen by all the peers of the Route Views route collector on an hourly basis. Several events are visible in the plot, such as the busting of the Internet bubble in 2001, and if one looks closely, the effects of the global financial crisis in 2009.

What is perhaps surprising is one ongoing event that is not visible in this plot: since 2011, the supply of IPv4 addresses has been progressively constrained as the free pools of the various Regional Internet Registries have been exhausted. Yet there is no visible impact on the rate of growth of the number of announced prefixes in the global routing system since 2011.

BGP is not just a reachability protocol. Network operators can manipulate traffic paths using selective advertisement of more specific addresses, and allow BGP to be used as a traffic engineering tool.

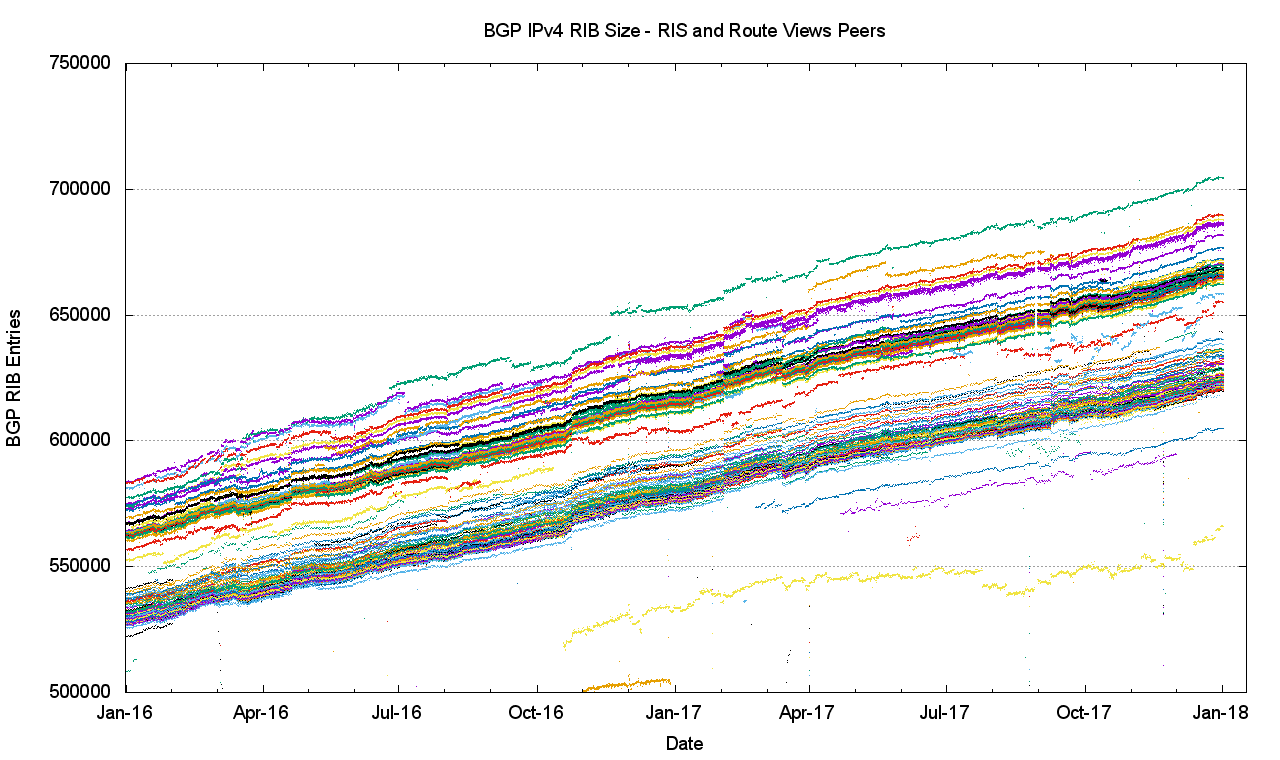

These more specific advertisements often have a restricted propagation. This is evident in Figure 2, where I’ve combined the BGP RIB counts from both the Route Views peers and the peers of the RIPE NCC’s Routing Information Service (RIS).

There are two distinct bands in this plot; the upper band is the Route Views peers and the lower band is generated by the RIS peers. The RIS peers, which are predominately located in Europe, appear to have 30,000 fewer prefixes, and cluster more tightly around their mean as compared to the set of Route Views peers.

Figure 2 illustrates an important principle in BGP, that there is no single authoritative view of the Internet’s inter-domain routing table — all views are in fact relative to the perspective of each BGP speaker.

It also illustrates that at times the cause of changes in routing is not necessarily a change at the point of origination of the route which would be visible to all BGP speakers across the entire Internet, but it may well be a change in transit arrangements within the interior of the network that may expose, or hide, collections of routes.

The issue of the collective management of the routing system as a single entity could be seen as an instance of a “tragedy of the commons”, where the self-interest of one actor in attempting to minimize its transit service costs becomes an incremental cost in the total routing load that is borne by other actors. To quote the Wikipedia article on this topic “In absence of enlightened self-interest, some form of authority or federation is needed to solve the collective action problem.”

This appears to be the case in the behaviour of the routing system, where there is an extensive reliance on enlightened self-interest to be conservative in one’s own announcements, and the actions of a small subset of actors are prominent because they fall well outside of the conventional conservative ‘norm’ of inter-domain routing practices.

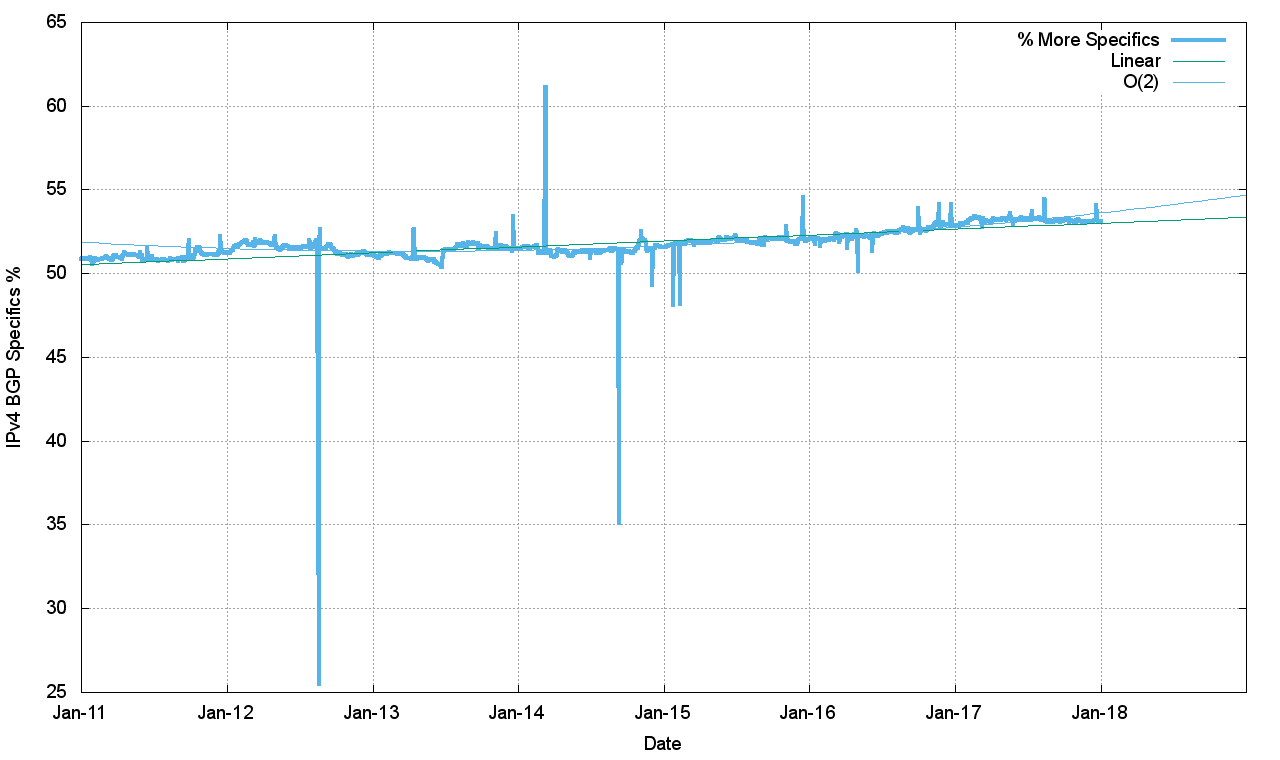

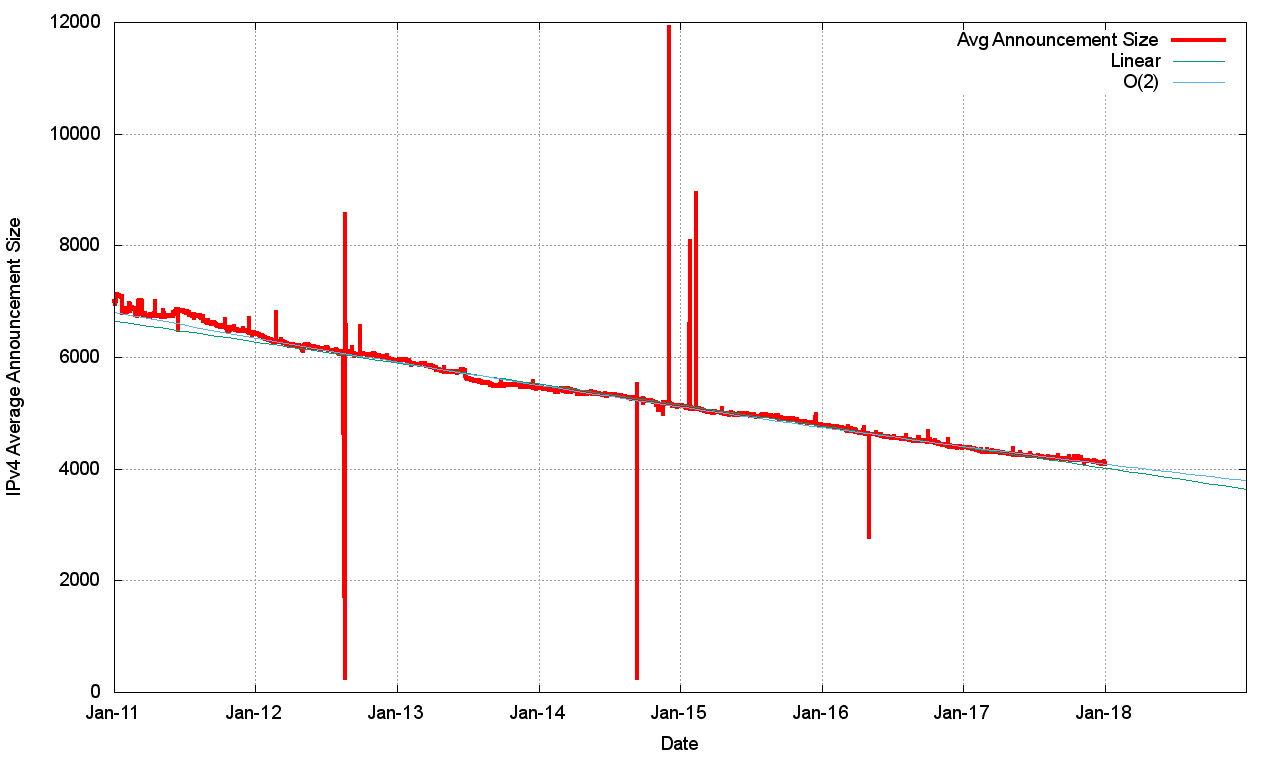

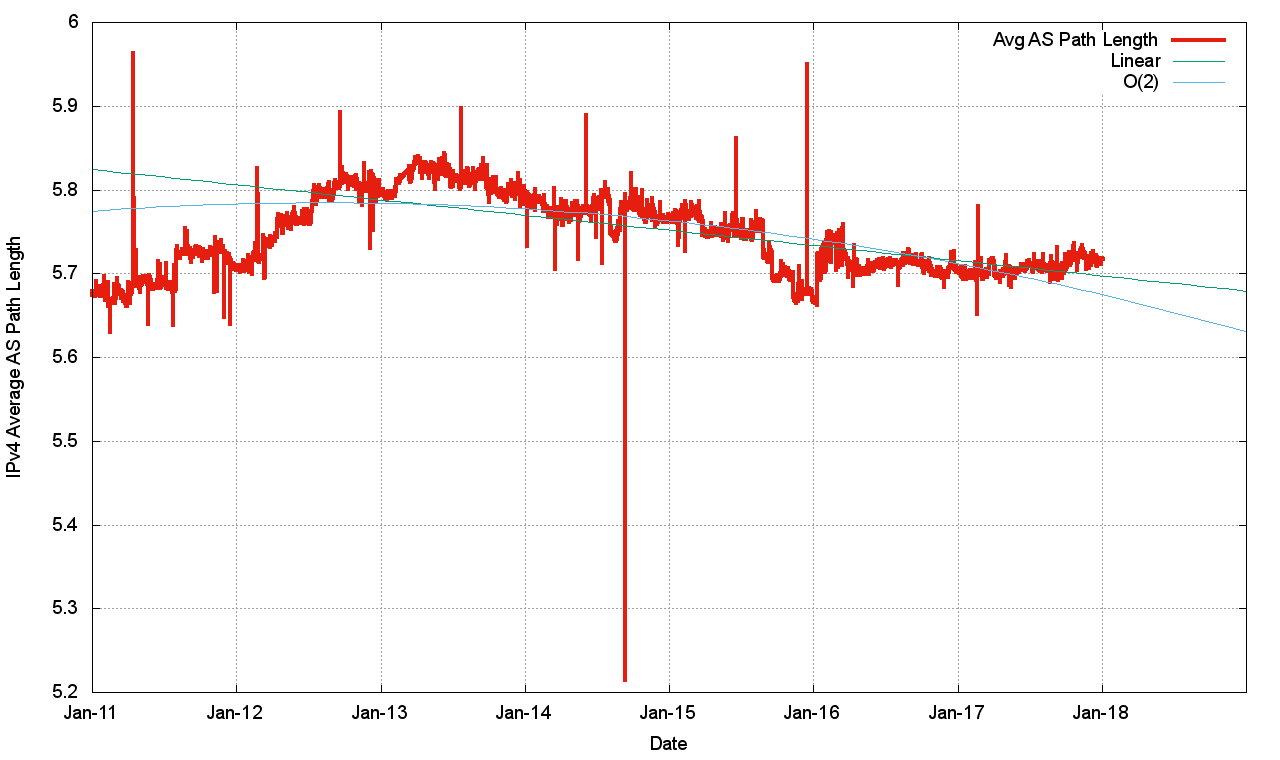

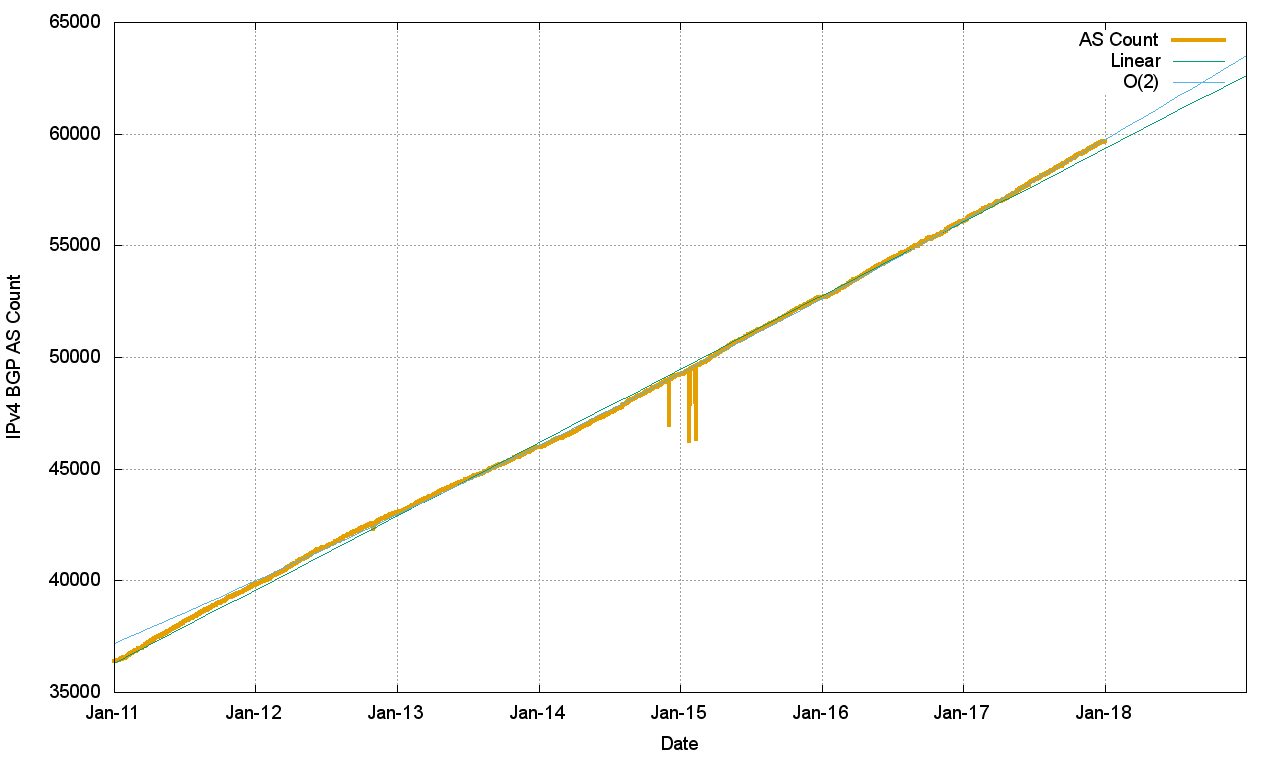

The next collection of plots (Figures 3 through 12) show some of the vital statistics for IPv4 in BGP since the start of 2011 to the end of 2017.

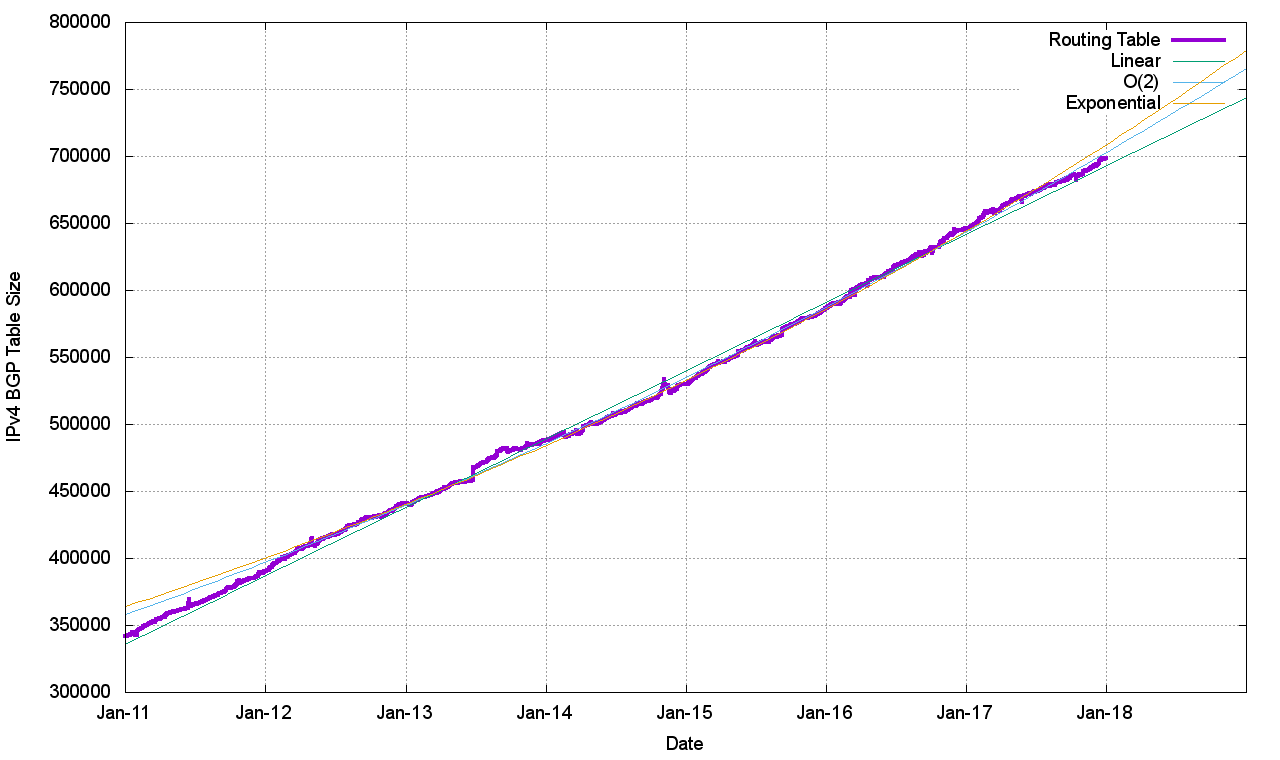

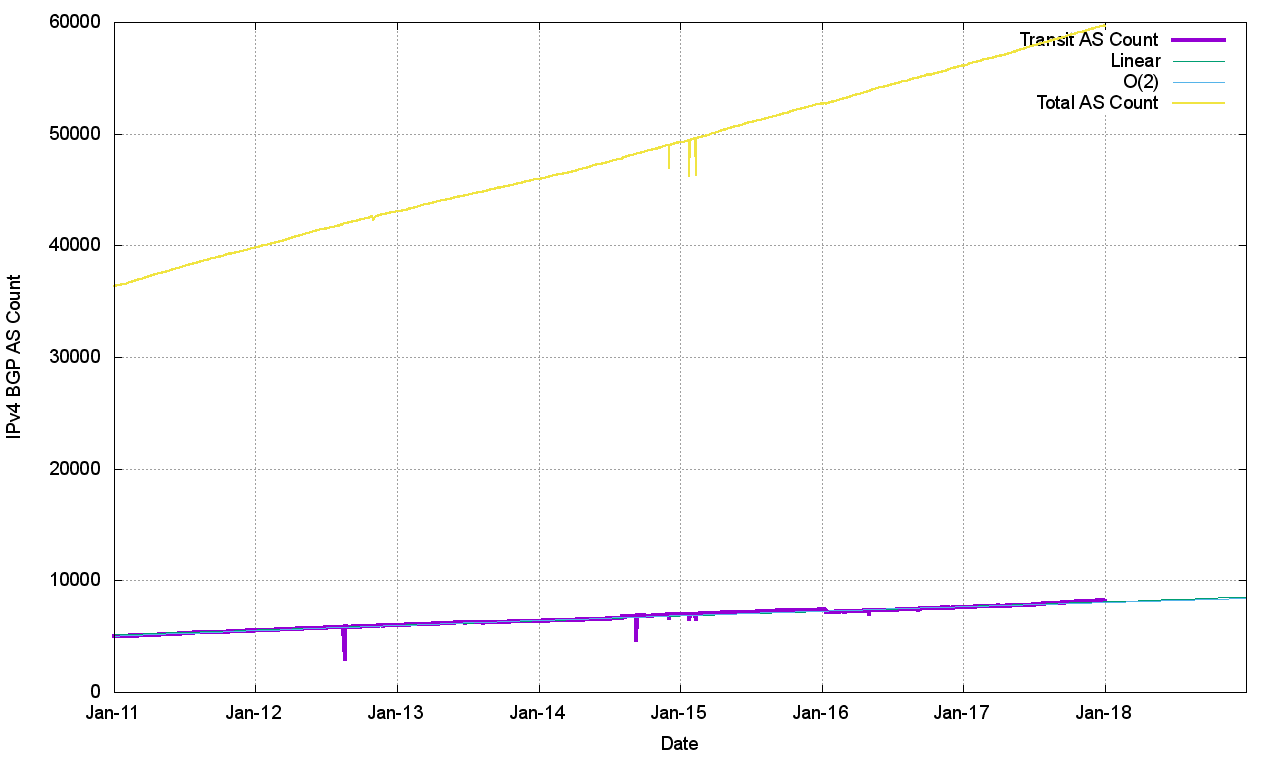

Figure 3 shows the total number of routes in the routing table over this period. This is a classic ‘up and to the right’ Internet trajectory, but it should be noted that growth trends in the Internet today are strongly aligned to a modest linear growth model.

Over this period, we had the exhaustion of the IPv4 address space pools in IANA in January 2011, APNIC in April 2011 (serving the Asia Pacific region), in the RIPE NCC in September 2012 (serving Europe, the Middle East and parts of Central Asia), LACNIC in May 2014 (serving Latin America and the Caribbean), and ARIN in September 2015 (serving North America, and some Caribbean islands).

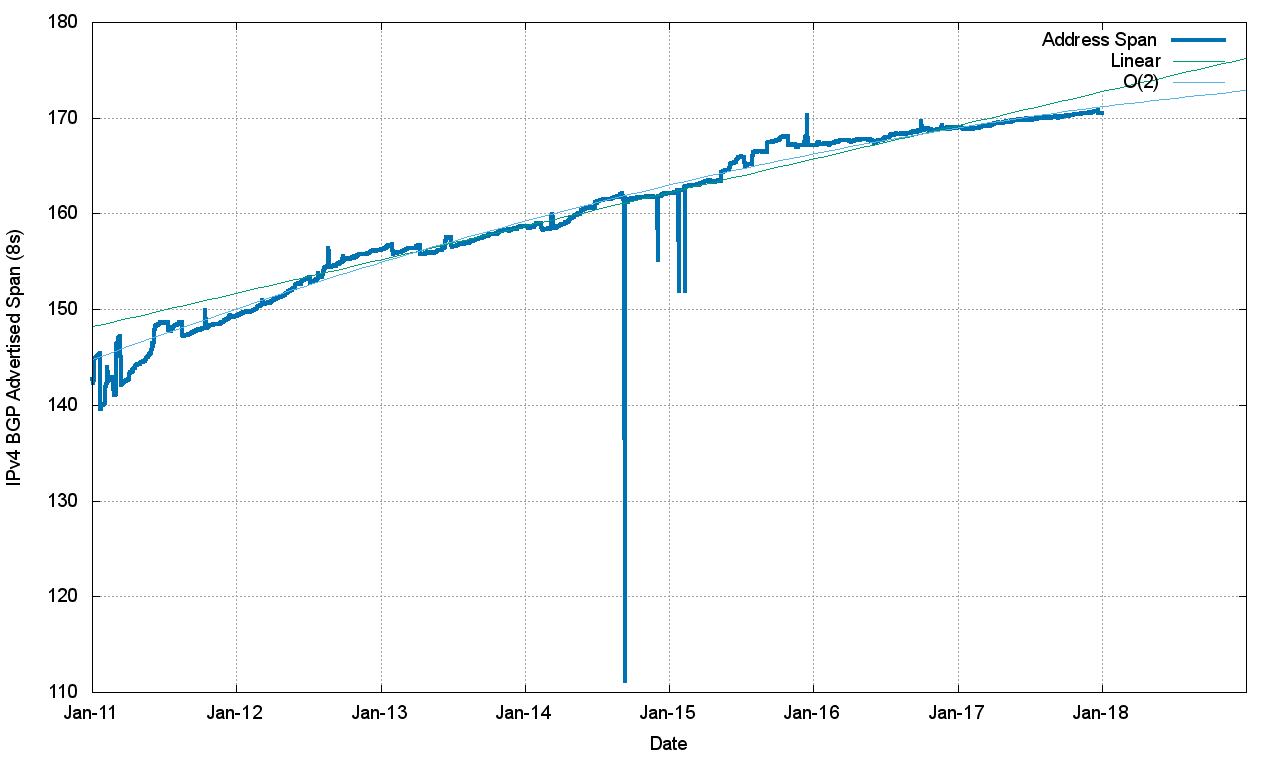

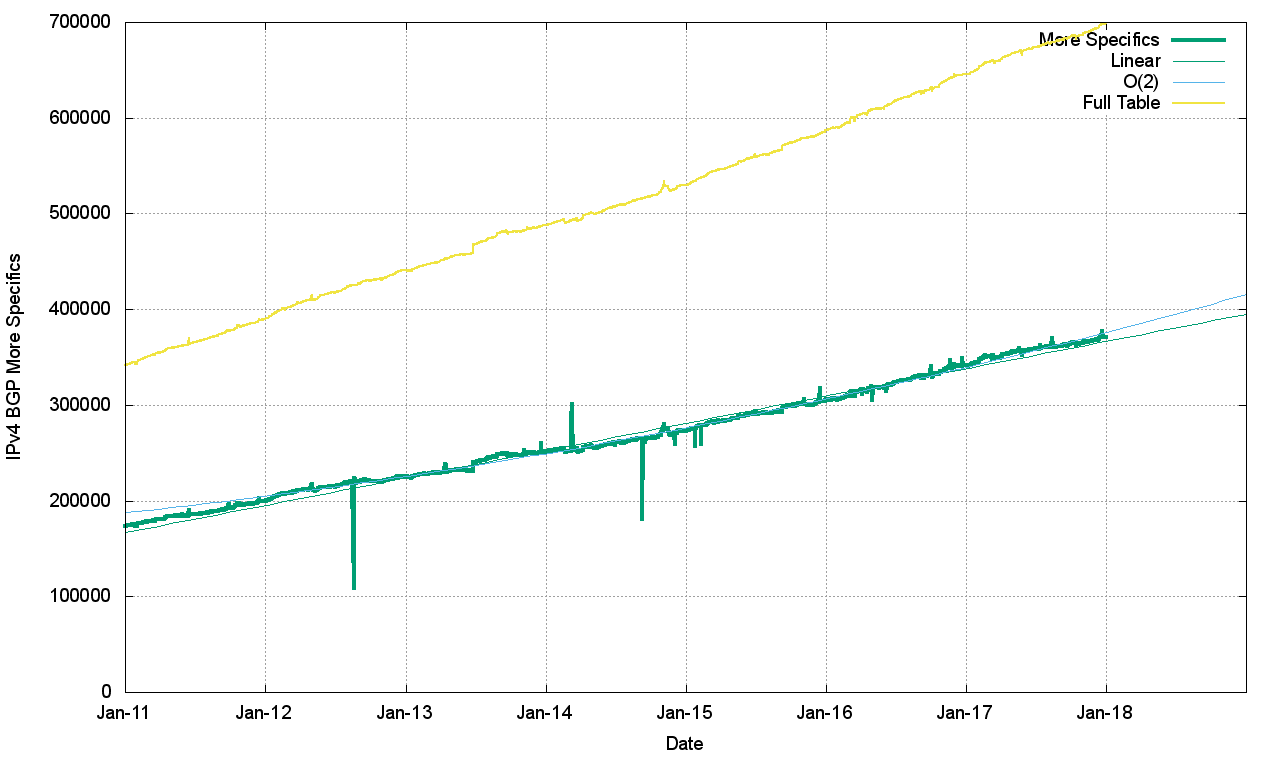

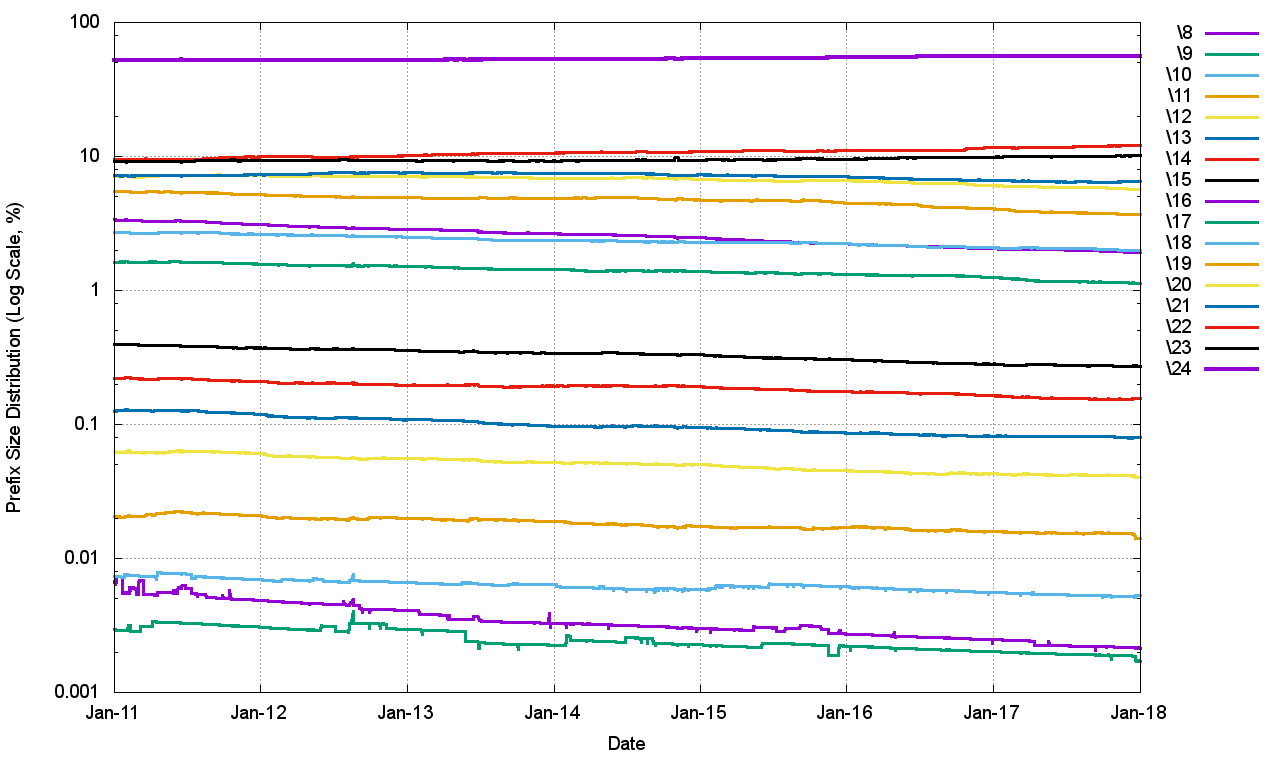

The six-year period since the start of 2011 has seen the span of addresses advertised in the routing system slowing down (Figure 4). However, at the same time there has been a consistent level of growth in the number of entries in the routing table over the same period.

The result of these two factors is that the average announcement in the IPv4 routing table is spanning fewer addresses, or, to put it another way, the granularity of the IPv4 routing space is getting finer.

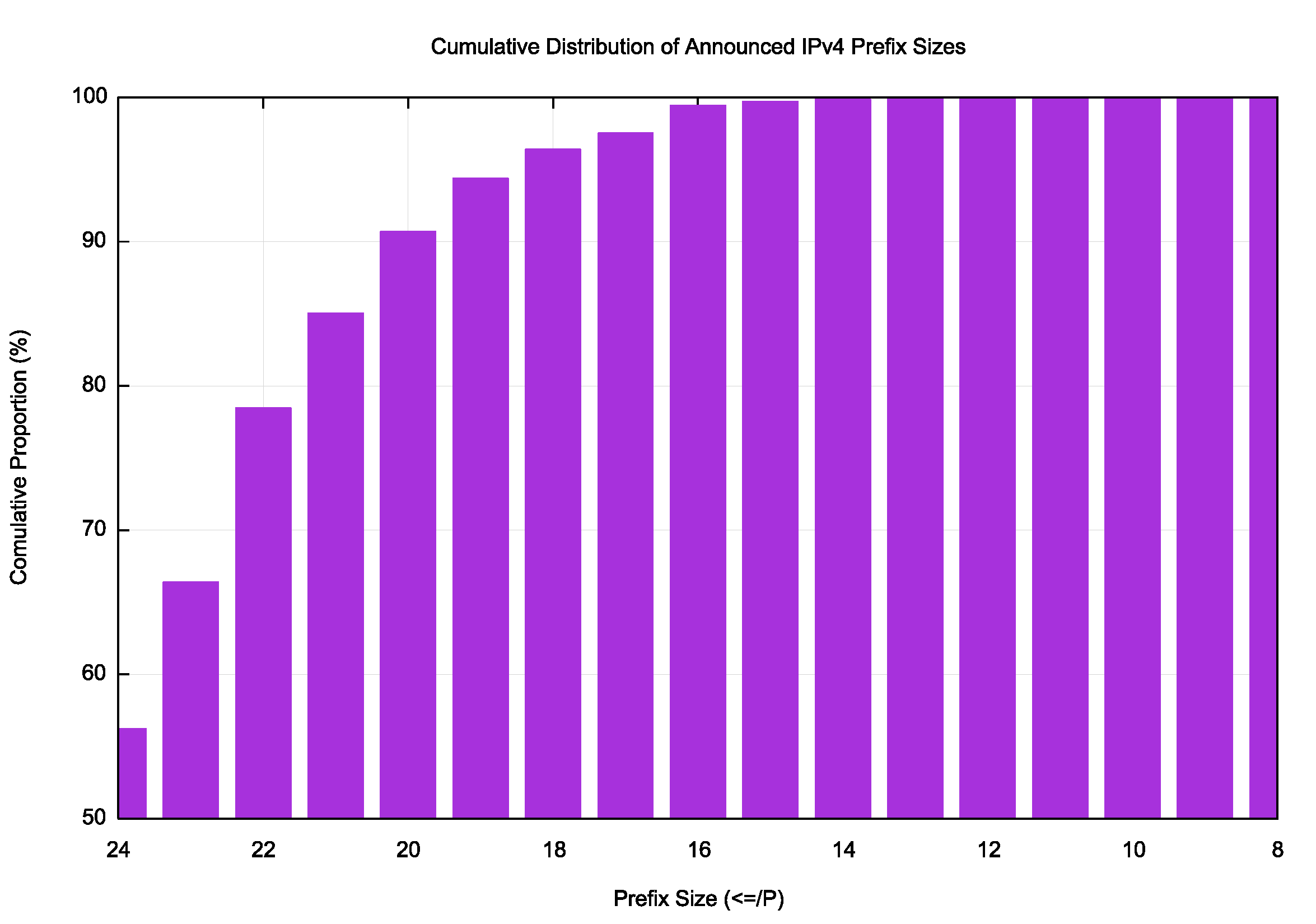

As Figure 7 shows, the average BGP announcement size has dropped from 7,000 host addresses at the start of 2011 to 4,000 addresses at the end of 2017. These days some 90% of all announced prefixes are of size /20 or smaller (Figure 12).

The topology of the network has remained relatively consistent, with the growth in the Internet being seen as increasing density of interconnectivity, rather than through extending transit paths, so the average AS path length has remained relatively constant at 5.7 for this period for this observation AS (Figure 8).

The summary of the IPv4 BGP network over the 2015-2017 period is shown in Table 1.

| Jan-15 | Jan-16 | Jan-17 | Jan-18 | 2014 growth | 2015 growth | 2016 growth | 2017 growth | |

| Prefix Count | 530,000 | 587,000 | 646,000 | 699,000 | 9% | 11% | 10% | 8% |

| Root Prefix | 257,000 | 281,000 | 304,000 | 328,000 | 8% | 9% | 8% | 8% |

| More Specs | 287,000 | 306,000 | 342,000 | 371,000 | 14% | 7% | 12% | 8% |

| Address Span (/8s) | 162.1 | 167.2 | 169.0 | 170.5 | 2% | 3% | 1% | 1% |

| AS Count | 49,000 | 52,700 | 56,100 | 59,700 | 7% | 8% | 6% | 6% |

| Transit AS | 7,000 | 7,600 | 7,800 | 8,500 | 9% | 9% | 3% | 9% |

| Stub AS | 42,000 | 45,100 | 48,300 | 51,200 | 8% | 7% | 7% | 16% |

In terms of advertised prefixes the size of the routing table continues to grow, but the 8% recorded through 2017 is slightly than the 10% p.a. which is the average of the previous three years. The number of routed stub AS numbers (new edge networks) grew by 6% in 2017, which is again slightly smaller than the growth rate of the previous two years.

The effects of increasing scarcity of IPv4 addresses is evident, with the span of advertised networks growing by just 1% through 2017. It appears that the drivers for growth in the IPv4 network in 2017 are slowing down compared to the previous three years. As IPv4 addresses are being placed under increasingly higher scarcity pressure, the compensatory move is that the advertised address space being divided up into smaller units, and presumably this routing change is accompanied by the increasing use of IPv4 Network Address Translation to accommodate the network’s growth pressures.

The overall conclusions from this collection of observations are:

- The IPv4 network continues to grow, but as the supply of new addresses is slowing down, what is now becoming evident is more efficient use of addresses, which results in the granularity of the IPv4 inter-domain routing system becoming finer.

- The density of inter-AS interconnection continues to increase.

- The growth of the Internet is not ‘outward growth from the edge’ as the network is not getting any larger in terms of average AS path change. Instead, the growth is happening by increasing the density of the network by attaching new networks into the existing transit structure and peering at established exchange points. This makes for a network whose diameter, measured in AS hops, is essentially static, yet whose density, measured in terms of prefix count, AS interconnectivity and AS Path diversity, continues to increase. This denser mesh of interconnectivity could potentially be problematic in terms of convergence times if the BGP routing system used a dense mesh of peer connectivity, but the topology of the network continues along a clustered hub and spoke model, where a small number of transit ASs directly service a large number of stub edge networks. This implies that the performance of BGP in terms of time and updates required to reach convergence continues to be relatively static.

The IPv6 BGP Table Data

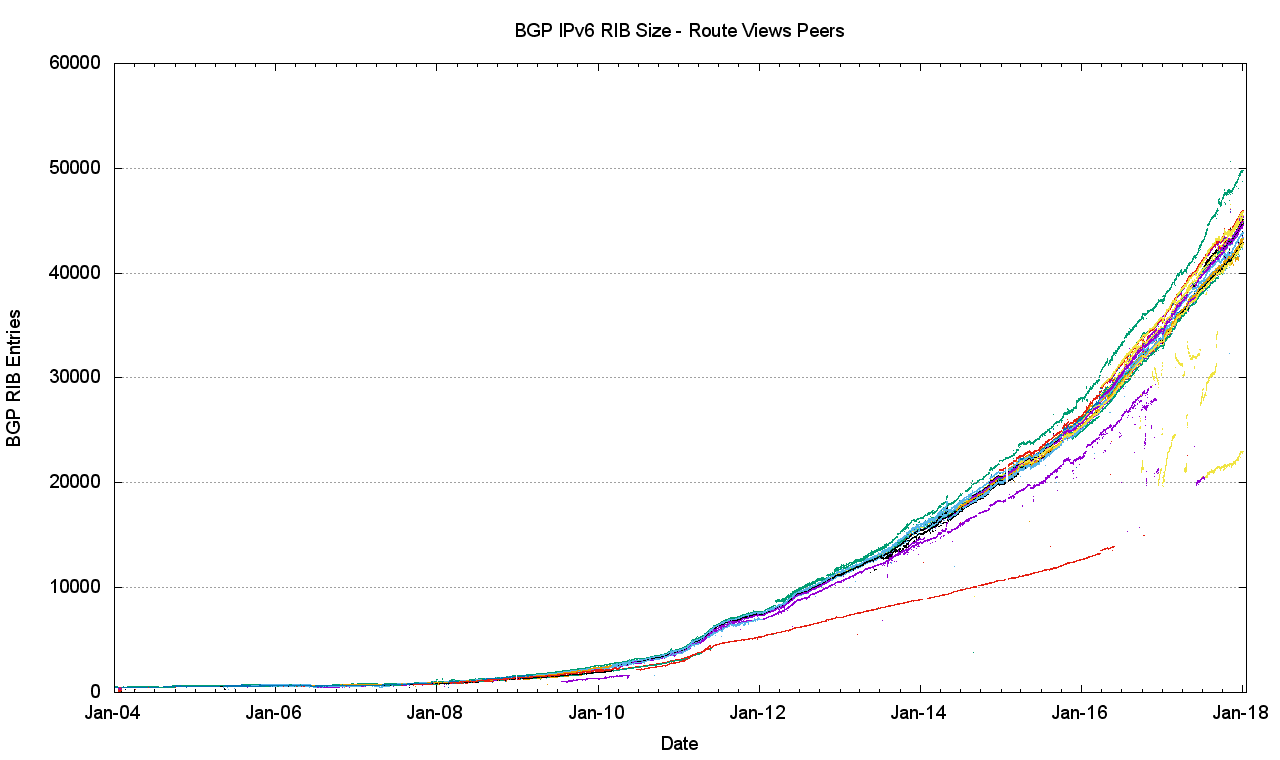

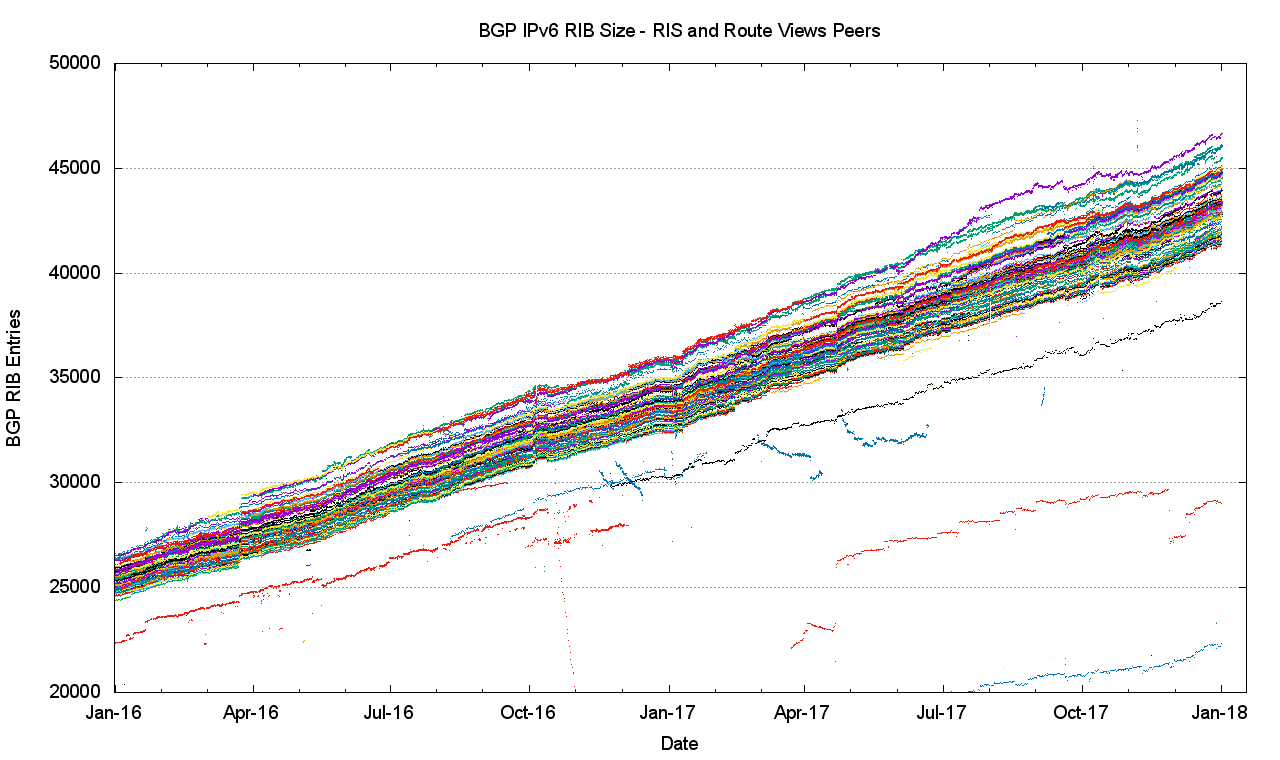

A similar exercise has been undertaken for IPv6 routing data. There is considerable diversity in the number of routes seen at various vantage points in the Internet, as shown when looking at the prefix counts advertised by all the peers of Route Views (Figure 13).

A more detailed look at 2016 and 2017 incorporating both Route Views and RIS (Figure 14) shows that in IPv6 there is no visible disparity in the route sets announced by RIS peers as compared to Route Views peers.

It is also evident that the increasing diversity between various BGP views as to what constitutes the ‘complete’ IPv6 route set, and the variance at the end of 2017 now span some 4,000 prefix advertisements.

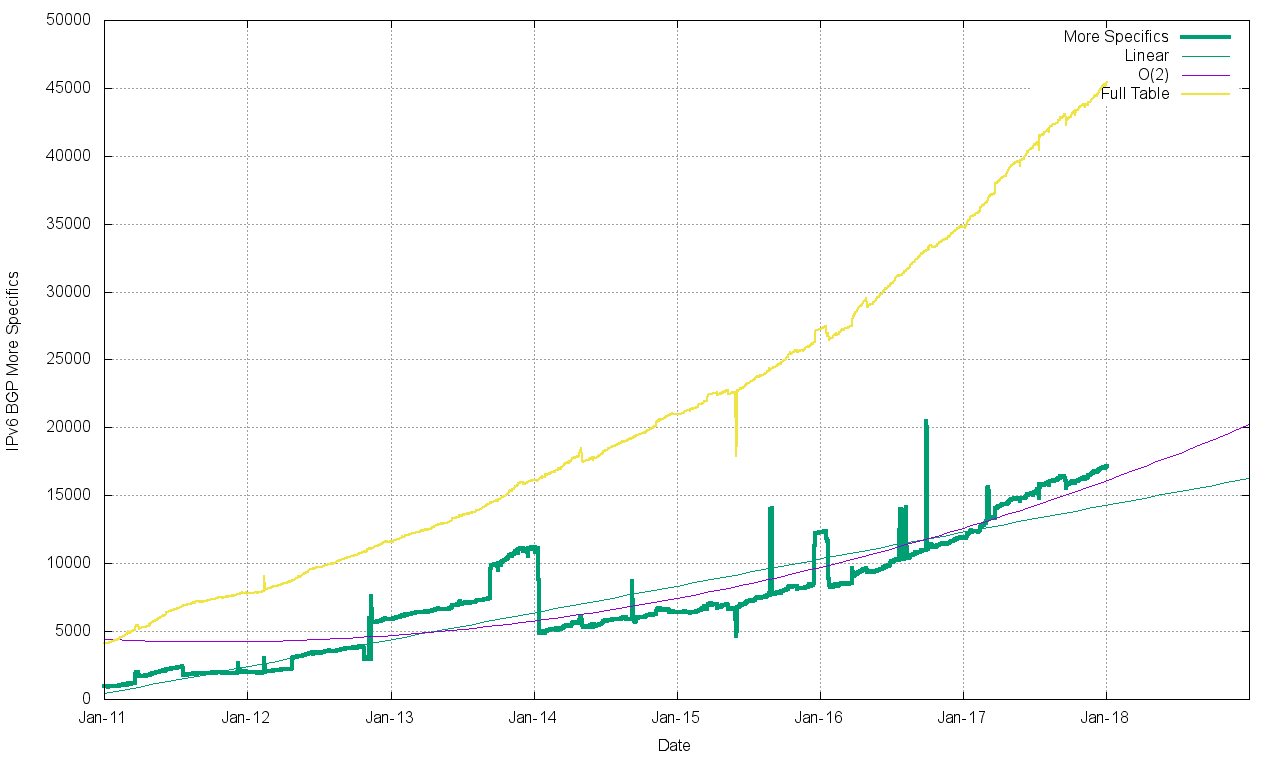

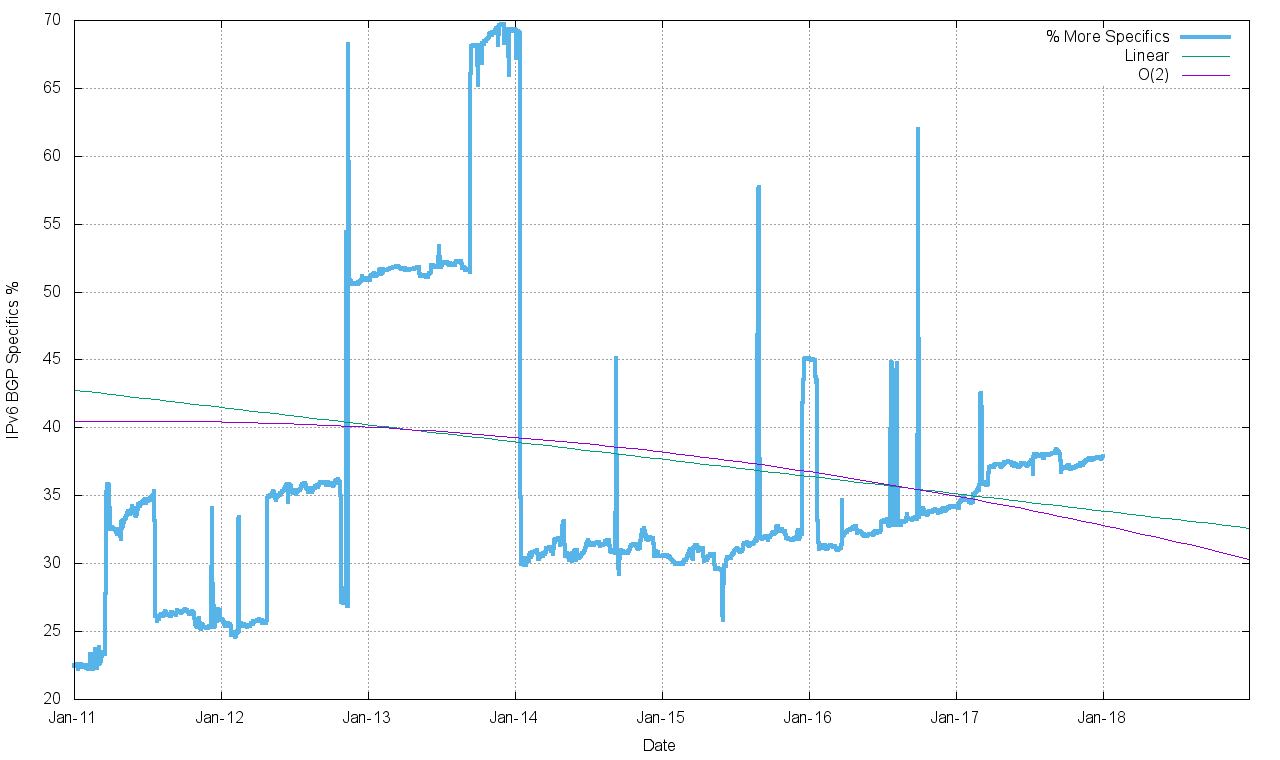

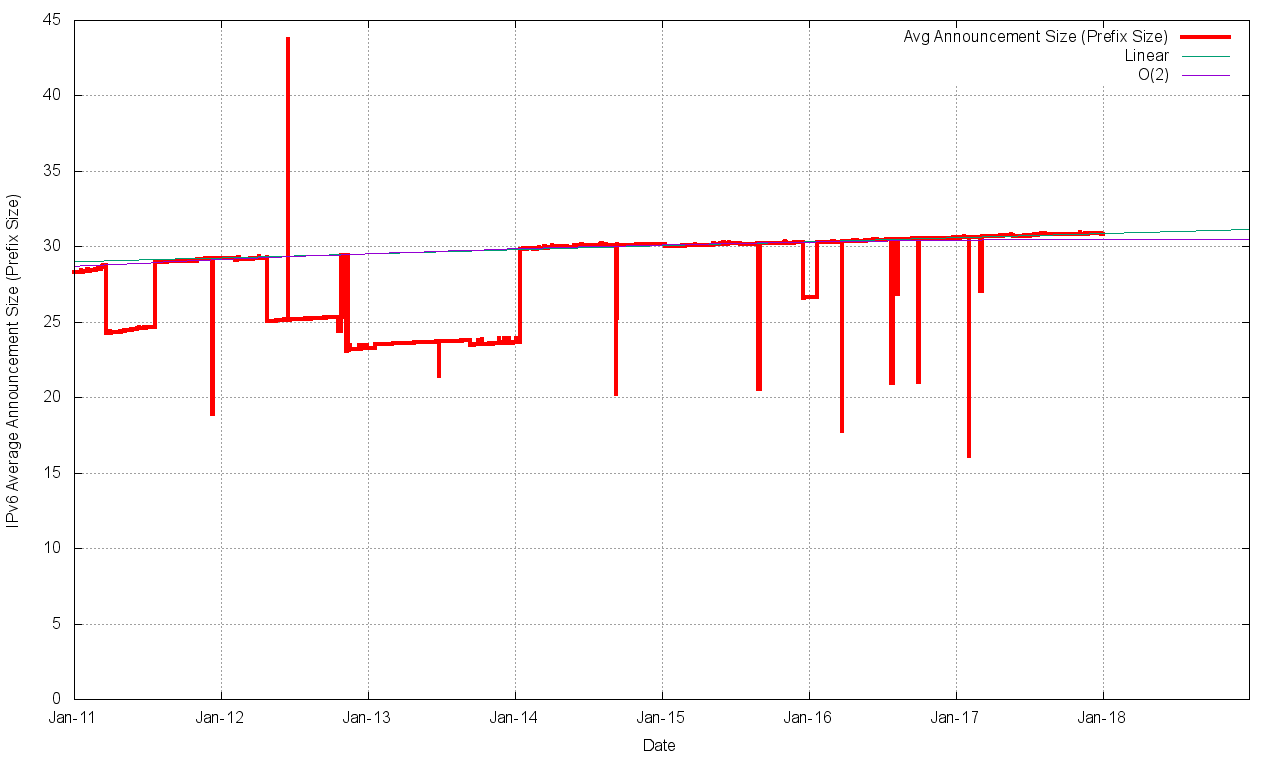

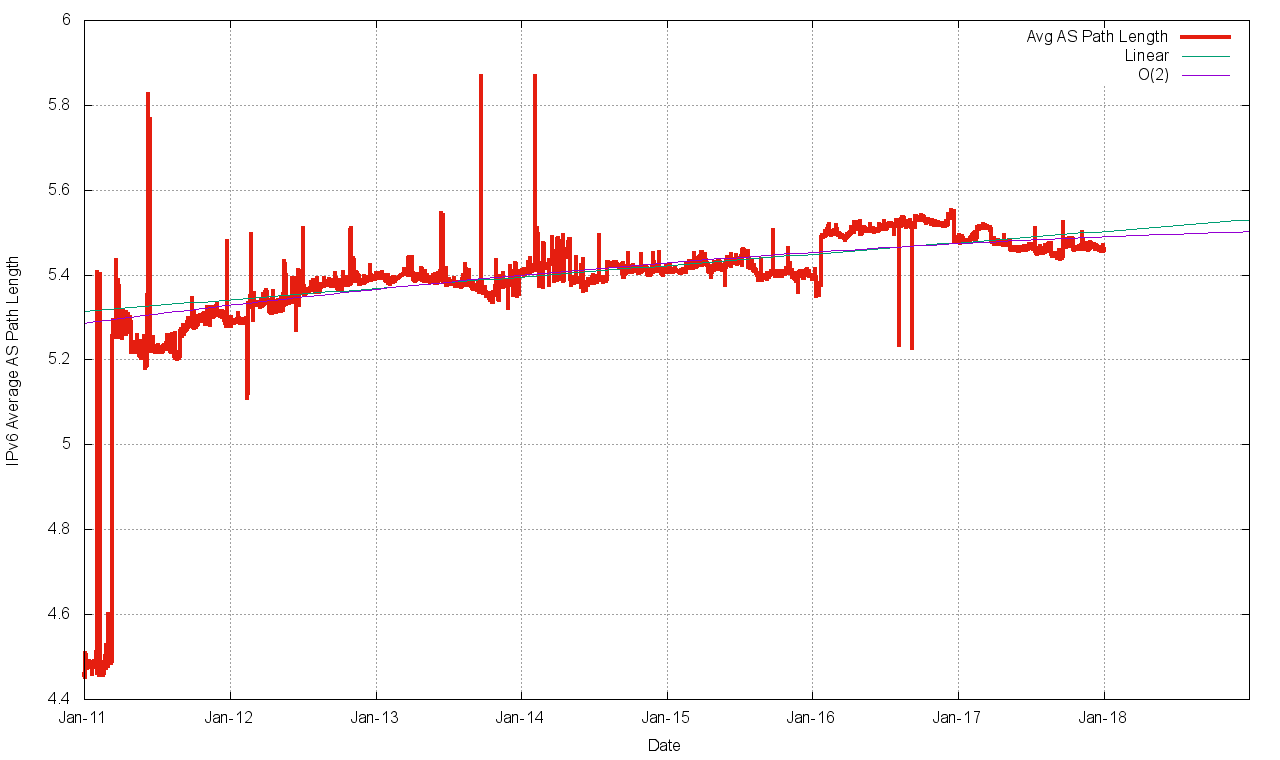

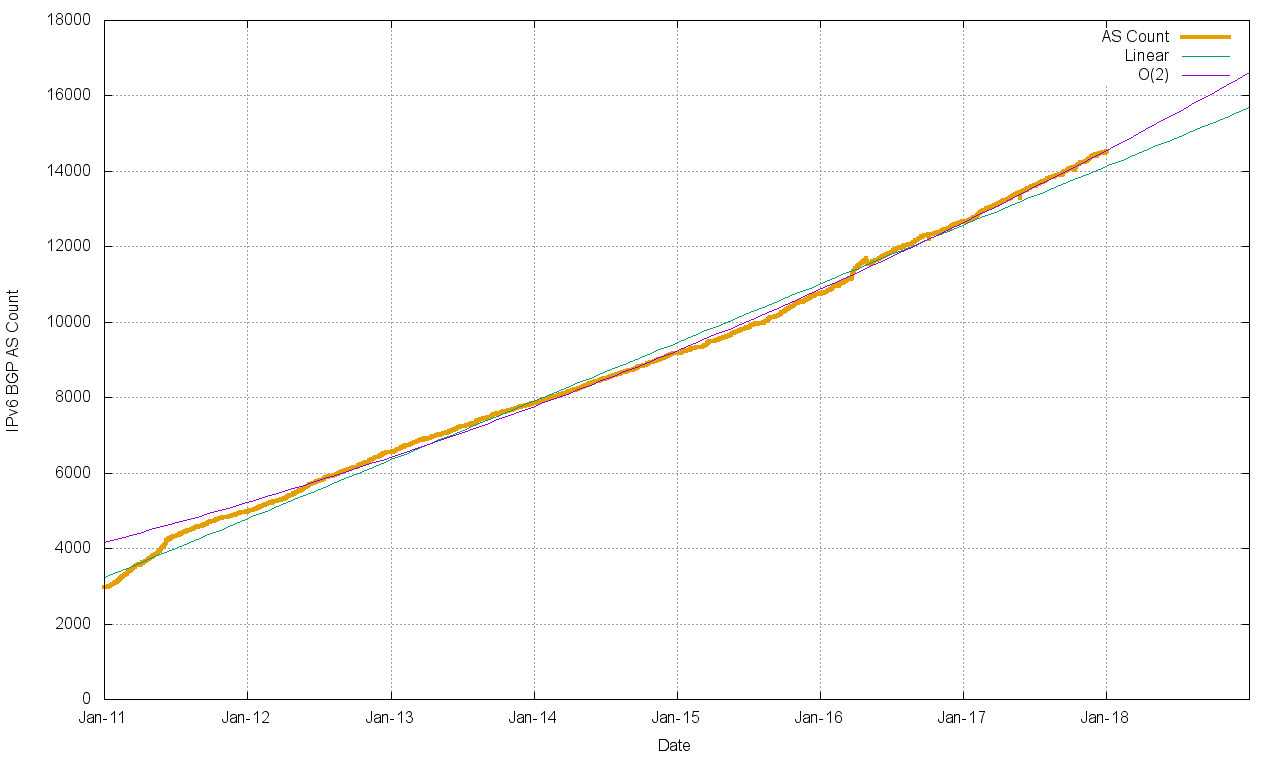

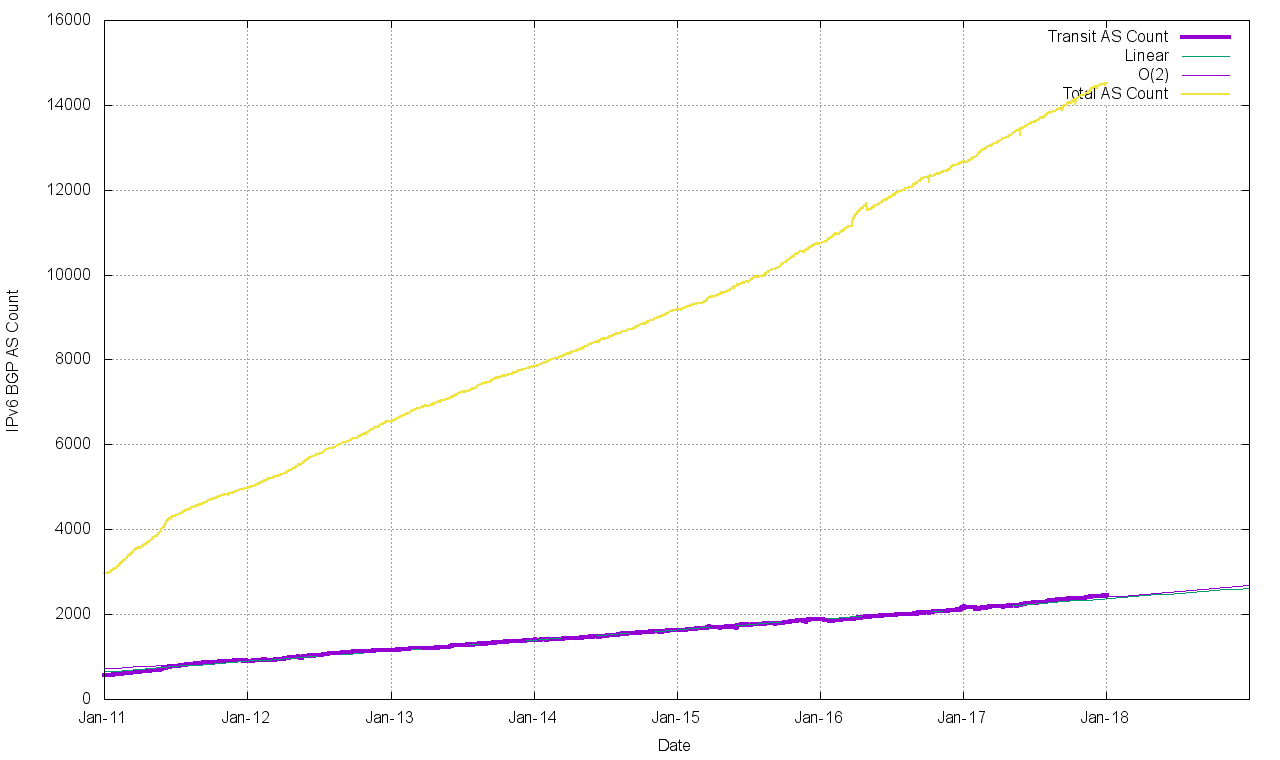

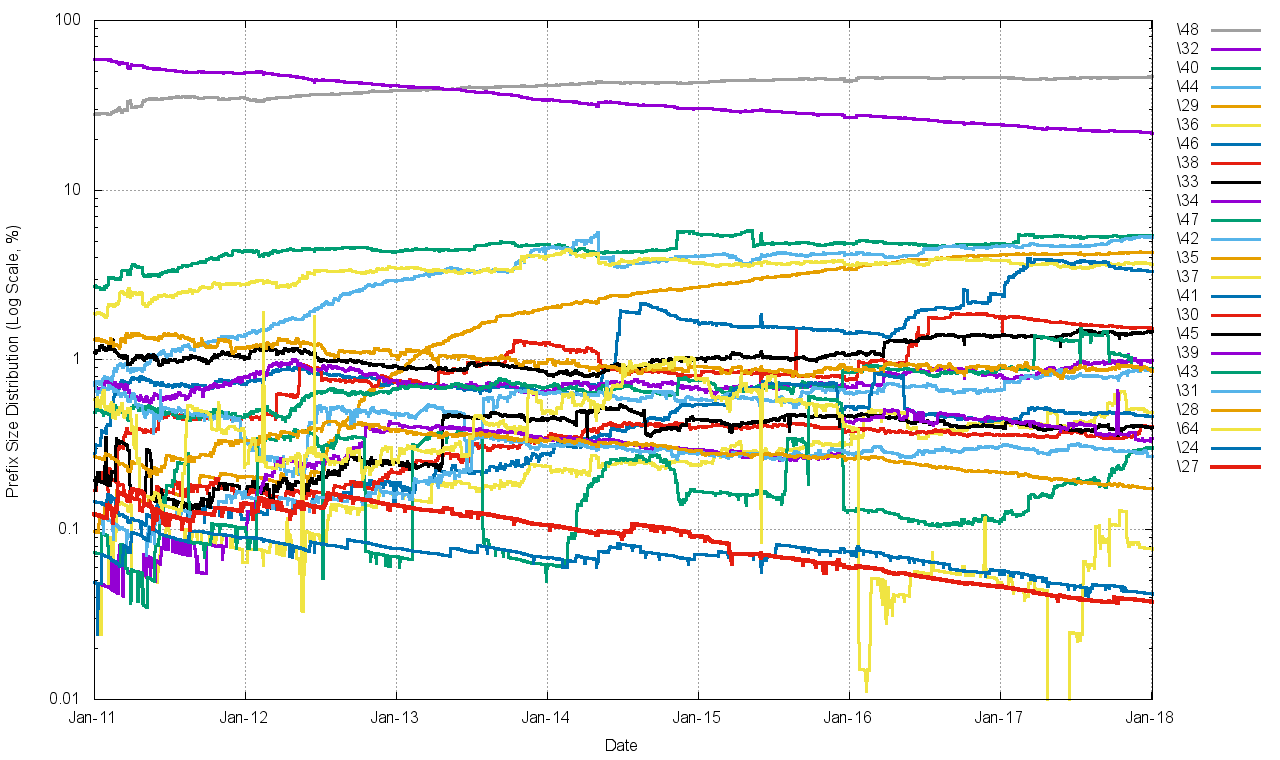

The comparable figures for the IPv6 Internet are shown in Figures 15 through 24.

The summary of the IPv6 BGP network over the 2014-2017 period is shown in Table 2.

| Jan-15 | Jan-16 | Jan-17 | Jan-18 | 2014 growth | 2015 growth | 2016 growth | 2017 growth | |

| Prefix Count | 21,000 | 27,200 | 34,800 | 47,500 | 26% | 30% | 28% | 31% |

| Root Prefix | 14,600 | 17,800 | 22,900 | 28,200 | 28% | 22% | 29% | 23% |

| More Specs | 6,400 | 9,400 | 11,900 | 17,500 | 21% | 47% | 27% | 47% |

| Address Span (/8s) | 58,200 | 71,000 | 76,600 | 102,700 | 4% | 22% | 8% | 34% |

| AS Count | 9,100 | 10,700 | 12,700 | 14,500 | 15% | 18% | 19% | 14% |

| Transit AS | 1,700 | 2,000 | 2,400 | 2,600 | 6% | 18% | 20% | 8% |

| Stub AS | 7,400 | 8,700 | 10,300 | 11,900 | 17% | 18% | 18% | 16% |

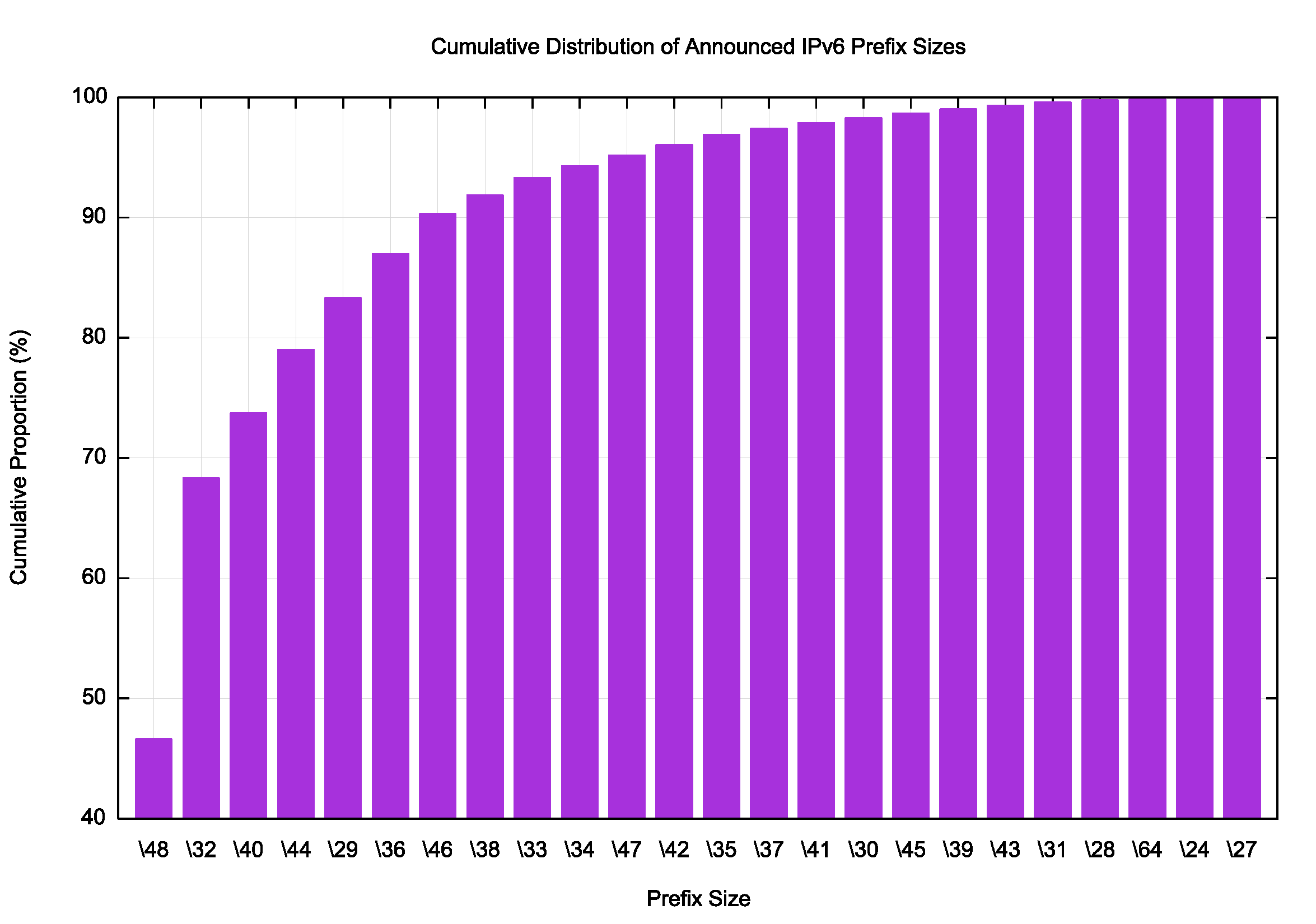

Routing advertisements of /48s are the most prevalent prefix size in the IPv6 routing table, and 90% of the table are composed of /48, /32, /40, /44, /29, /36 and /46. RIR allocations of IPv6 addresses show a different pattern, with 75% of address allocations either a /32 (56%) or a /29 (19%). Some 18% of allocations are a /48. What is clearly evident is that there is no clear correlation between an address allocation size and the advertised address prefix size.

BGP Dynamic Behaviour

We will now look at the profile of BGP updates across 2017 to assess whether the stability of the routing system, as measured by the level of BGP update activity, is changing.

IPv4 Stability

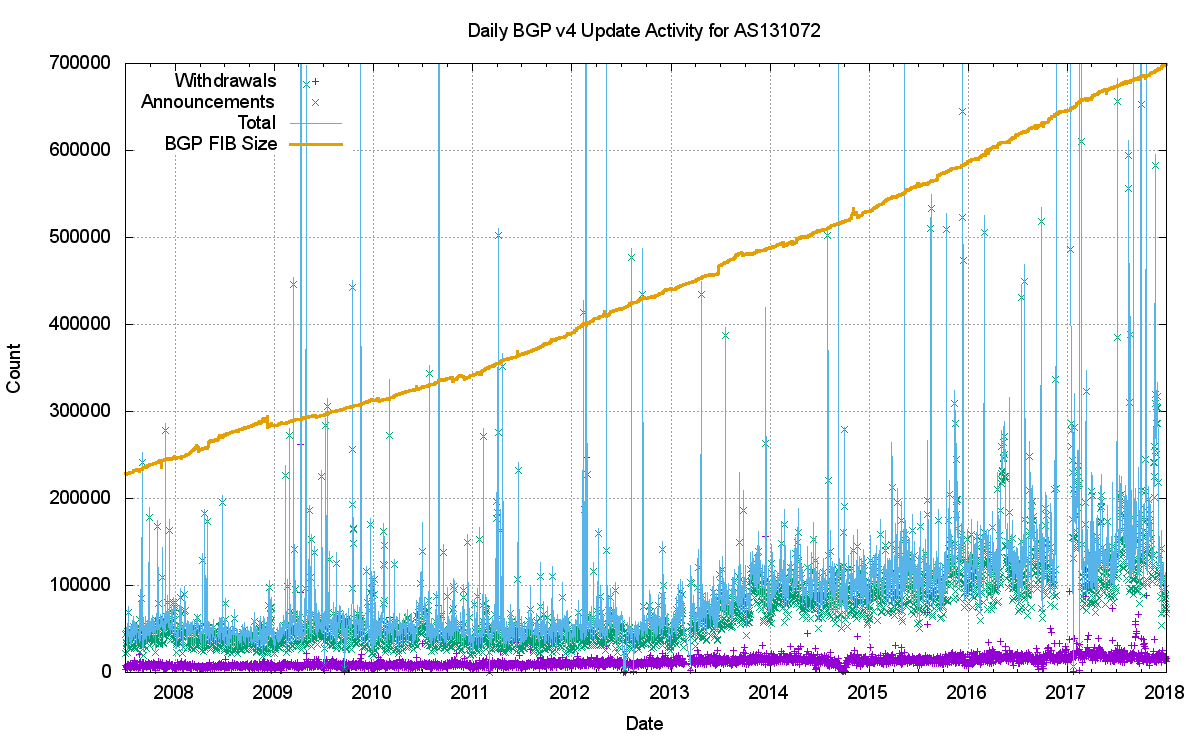

Figure 25 shows the daily update activity for the eBGP session at AS131072, since mid-2007. There are some aspects of BGP behaviour that are visible in this plot that do not have an obvious cause.

The first of these is the number of withdrawals. Since 2007 the number of advertised prefixes has risen from 230,000 to 700,000, yet the number of observed withdrawals has remained relatively constant at some 15,000 – 20,000 withdrawals per day. There is no particular reason why the withdrawal count should be steady while the number of announced prefixes has more than doubled.

The second is the number of update messages per day. This was steady at some 50,000 updates per day from 2007 until 2013. During 2013 the volume of updates doubled to some 100,000 updates per day, which it maintained for most of the ensuing 24 months.

During 2016 and 2017 the number of updates per day rose once more, approaching some 170,000 updates per day by the end of 2017. This is not exactly reassuring news for the routing system. It has been fortuitous that the BGP update rate has been held steady for so many years, as this has implied that the capability of BGP systems has not required constantly increasing processing capability. In the same way that there was no clear understanding of why the BGP update rate was steady for so many years, it’s also unclear why the rate has started to increase in 2016 and continues to increase across 2017. This makes efforts to attempt to stem this upward trend rather uncertain.

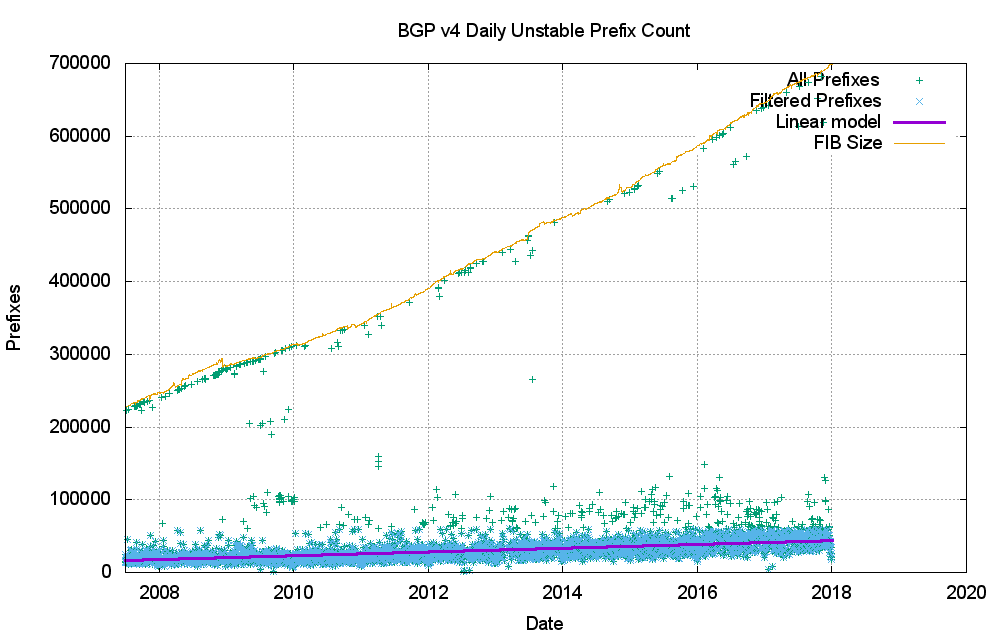

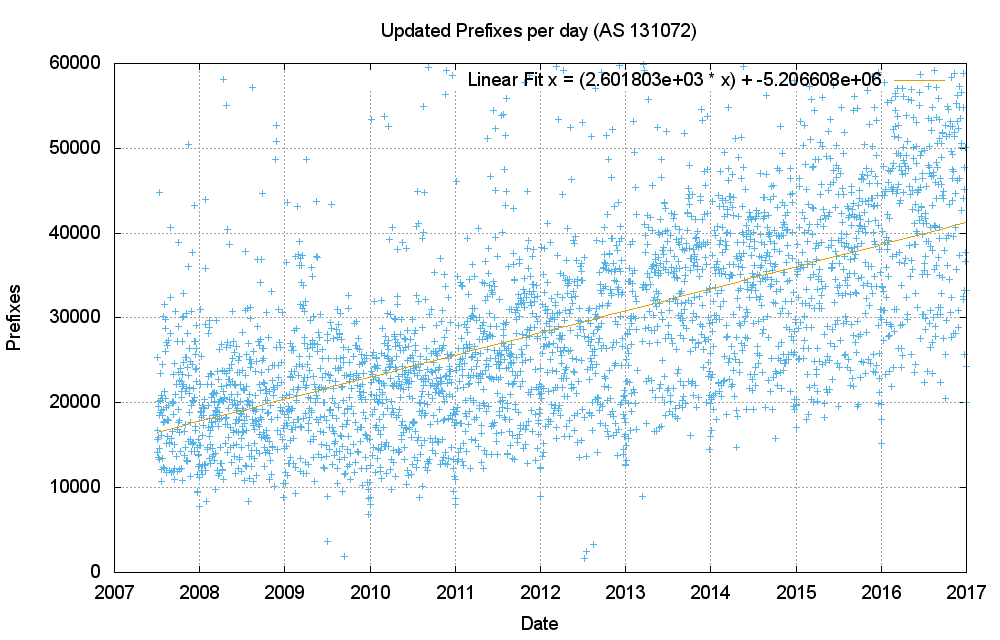

What is also intriguing is that most of these 170,000 updates per day are generated from a pool of between 20,000 to 40,000 prefixes. A plot of the daily number of different prefixes that are the subject of BGP updates is shown in Figure 26. While this is rising, there is no major change across 2013, so the heightened instability is likely due to more updates to reach convergence, rather than more unstable prefixes.

The number of unstable prefixes per day appears to be gradually increasing over the years. A least squares best fit shows a linear trend that increases the average daily unstable prefix count by 2,600 prefixes per year (Figure 27).

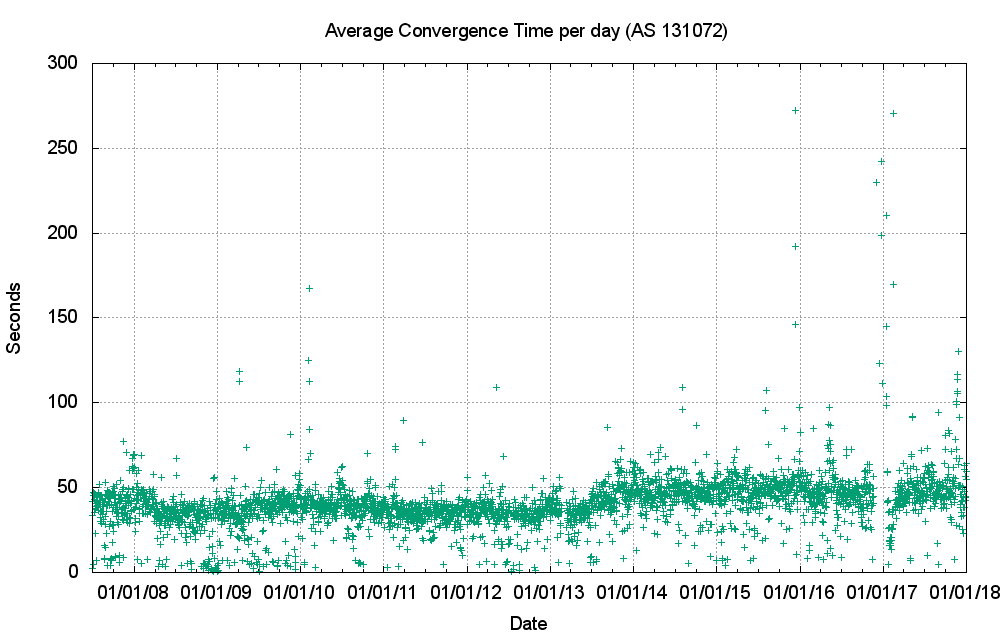

However, this increased count of the number of unstable prefixes and the increasing update count is not reflected in the measure of the time to reach a converged state. The average time for an unstable prefix to reach stability is still at some 50 seconds (Figure 28), and while it rose in 2013 from around 40 to 50 seconds, the number has remained at 50 seconds since then.

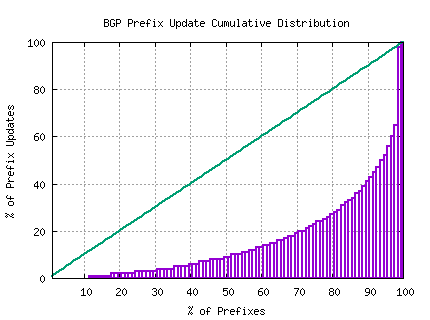

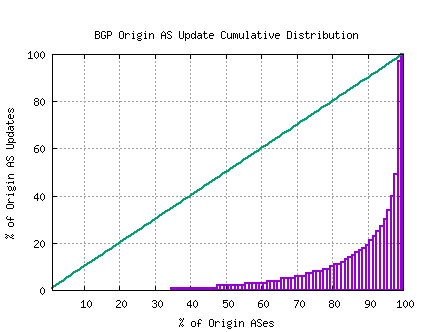

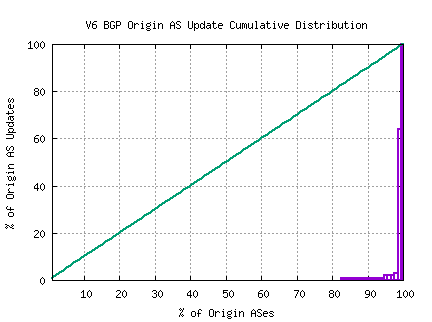

However, the instability in BGP is not widespread. Half of all the BGP updates over a period of a week are attributed to less than 10% of the unstable prefixes, and just 50 origin ASNs accounted for one third of all BGP IPv4 updates.

It appears that the network is generally highly stable and that a very small number of prefixes appear to be wedged into highly unstable configurations over periods that extend for weeks rather than hours. The cumulative distribution of BGP updates by prefix and by origin AS, shown in Figures 29 and 30 for the final week of 2017, shows the highly skewed nature of unstable prefixes in the routing system.

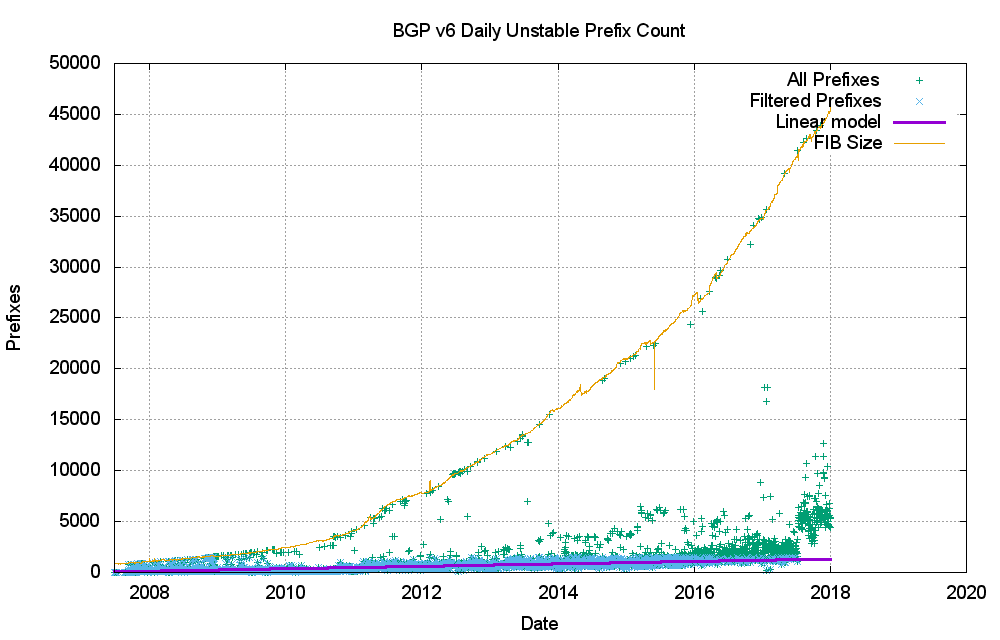

IPv6 Stability

Ideally, the IPv6 routing network should be behaving in a very similar manner to the IPv4 environment. It is a smaller network, but as the overlay IPv6 tunnels are phased out, the underlying connectivity for IPv6 should be essentially similar in terms of the connectivity of IPv4 (it would be anomalous to see two networks where one provided transit services to the other in IPv4, yet the opposite arrangement is used for IPv6).

So, given that the underlying topology should have strong elements of similarity across the two protocols, should we see the BGP stability profile of IPv6 appear to be much the same as IPv4 or not?

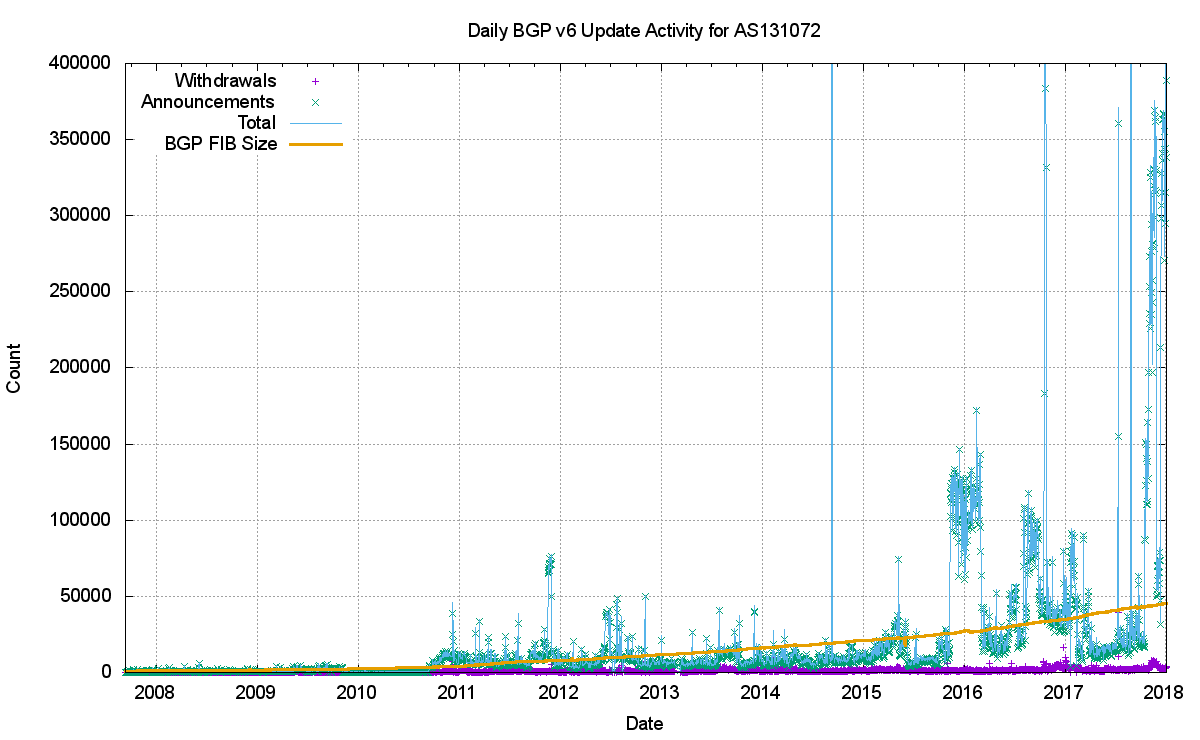

Figure 31 shows the profile of IPv6 updates since 2008. In common with IPv4, the number of withdrawals per day appears to be relatively constant over this period. The number of IPv6 BGP updates per day is quite different from IPv4. This number has been rising since 2015, and by the end of 2017 we are seeing some 350,000 updates per day.

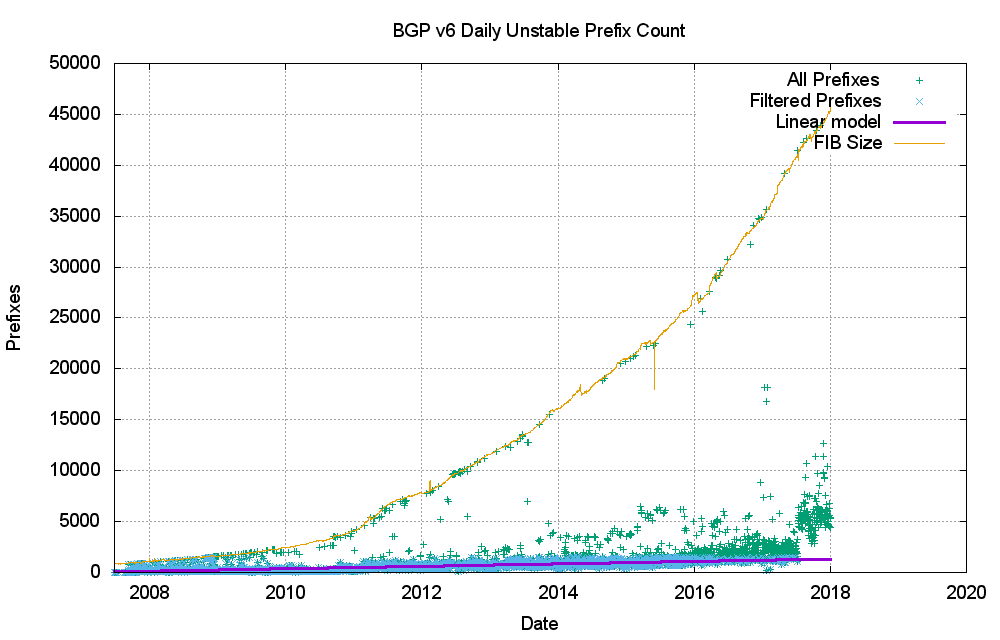

Figure 32 shows that the number of unstable prefixes has risen in the second half of 2017 — there are around 5,000 unstable prefixes per day. This five-fold increase in the number of unstable prefixes does not account for the more than ten-fold increase in the update rate, so it seems likely that a small number of prefixes are highly unstable.

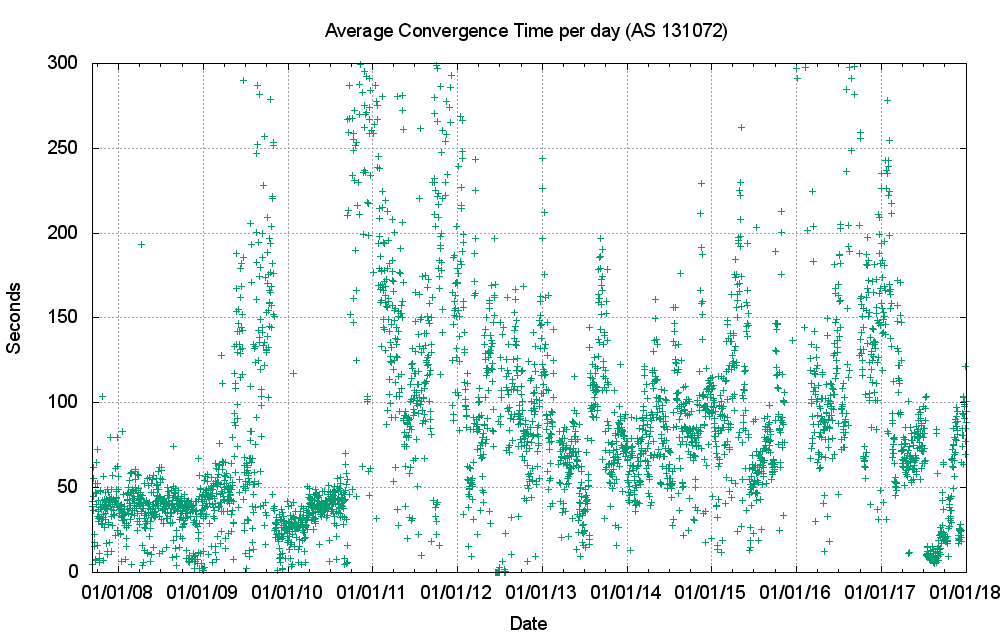

This greater instability in the IPv6 network is also visible in the daily average time to reach convergence (Figure 33). Prior to 2009, the average convergence time was less than 50 seconds, which was comparable to the IPv4 network at the time. However, this metric has increased significantly since then, and average daily convergence times now range from a low point of some 40 seconds to some 300 seconds.

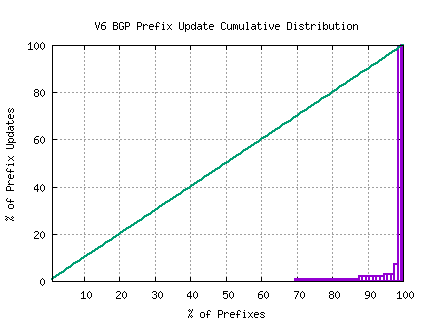

It is also evident that the distribution of updates across the set of announced prefixes and originating ASNs is more skewed than IPv4. The most unstable 50 IPv6 prefixes accounted for slightly more than one quarter of the total update volume, and the most unstable 50 Origin ASNs account for some 90% of the updates. The distribution of updates is shown in Figure 34 and 35.

It is not immediately obvious why IPv6 has this higher instability component than IPv4. A concern is that this instability remains a persistent condition as the IPv6 network continues to grow, which would create a routing environment that would impose a higher processing overhead than we had anticipated, with its attendant pressures on BGP processing capabilities in the network.

The Predictions

What can this data from 2017 tell us in terms of projections of the future of BGP in terms of BGP table size?

At the outset, it’s necessary to observe that this is a time of extreme uncertainty in the BGP prediction business. With this caveat that we are now heading deep into highly speculative areas, and the associated warning that the predictions being made here come with a very high level of uncertainty, let’s look at the predictions for the Internet’s routing system for the coming few years.

Forecasting the IPv4 BGP Table

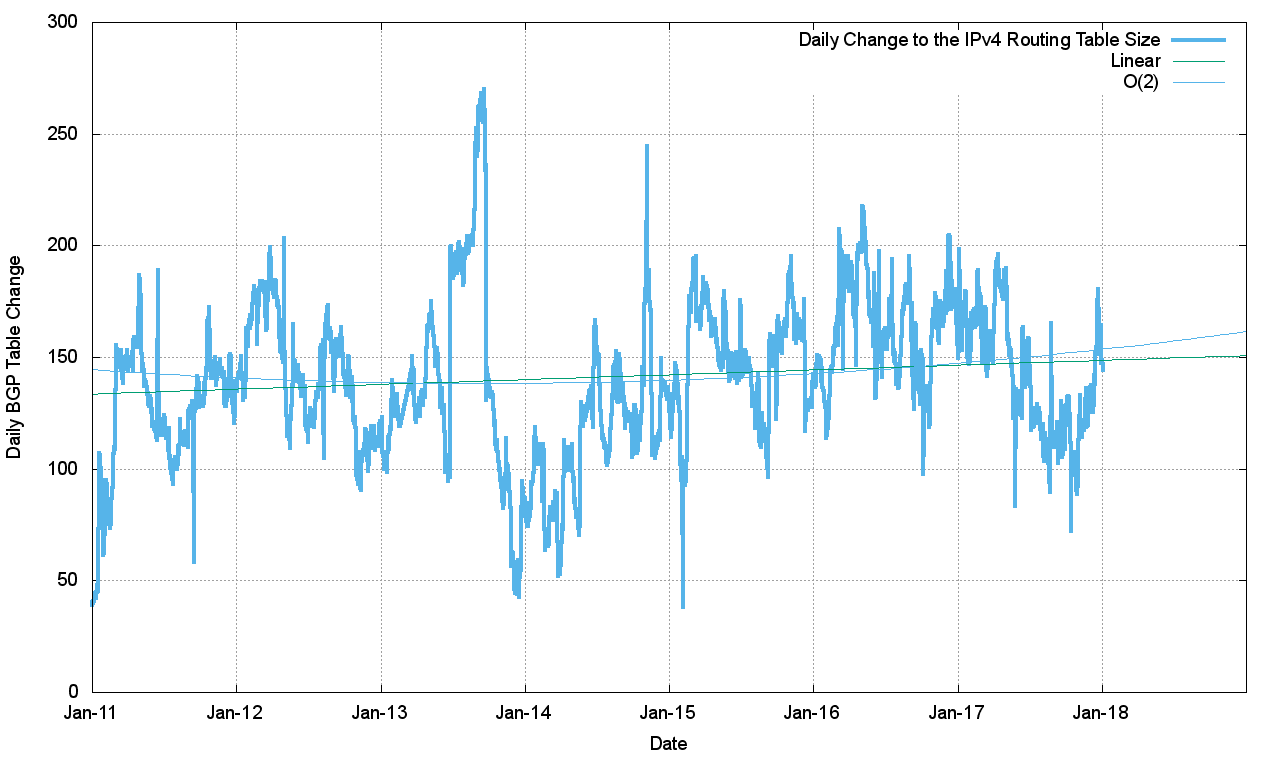

Figure 36 shows the data set for BGP from January 2014 until January 2017. This plot also shows the fit of these most recent three years of data to various models. The first order differential, or the rate of growth, of the BGP routing table is shown in Figure 37. The seven-year average rate of growth of the routing table appears be holding steady between 140 and 160 additional entries per day. This data suggests that a reasonable prediction of IPv4 BGP table size can be generated using a linear growth model of approximately 150 additional routing entries per day.

| IPv4 Table | IPv4 Prediction | |

| Jan 2014 | 488,011 | |

| Jan 2015 | 529,806 | |

| Jan 2016 | 586,879 | |

| Jan 2017 | 645,974 | |

| Jan 2018 | 698,714 | 693,000 |

| Jan 2019 | 744,000 | |

| Jan 2020 | 795,000 | |

| Jan 2021 | 846,000 | |

| Jan 2022 | 897,000 | |

| Jan 2023 | 948,000 |

It’s difficult to portray this prediction as reasonable under the current circumstances. Given the last ‘normal’ year of supply of available IPv4 addresses to fuel continued growth in the IPv4 Internet was 2010, why has the growth of the IPv4 routing table occurred with such regularity?

A Second Look at IPv4 Routing Advertisements

These predictions for the size of the IPv4 BGP network growing by a continued 51,000 new routing entries per year assume the near-term future will continue to play out much the same as the recent past. But, as we’ve noted, the issues related to IPv4 address exhaustion make this assumption somewhat implausible. So, let’s take a more detailed look at IPv4 across 2016, and to do this I’ll take a comparison of a snapshot of the routing table as of the start of 2016 to that at the end of the year.

At the start of the year the BGP routing table in AS131072 had 586,917 entries, and at the end of the year, it had 646,059 entries. The routing table grew by 59,141 entries through the year – right?

Mathematically that is correct, but it’s not the entire story. There were only 502,846 routing entries that were in both routing snapshots. Some 67,504 routes were present at the start of the year, but not at the end, and 126,645 entries that were in the end of year snapshot, but not at the beginning of the year.

The issue here is that the BGP is not just used to glue the Internet together in a reachability sense. Routing is also the only tool we have to adjust the path taken by incoming traffic. So, in a sense, we could say that the routing table contains the cross product of reachability and routing policies. At any point in time, there are a collection of ‘traffic engineering’ prefixes, and a set of reachability prefixes. So, can we differentiate between what appears to be the background of traffic engineering route changes from the routes that appear to be announcing reachability to previously unreachable addresses?

One approach is to divide the routing table into ‘root’ prefixes that announce reachability, and ‘more specific’ prefixes that refine this reachability for parts of this announced space. At the start of 2016, there were 286,249 root prefixes and 300,669 more specifics. At the end of 2016 there were 309,092 root prefixes and 336,947 more specifics. That’s a net growth of 22,843 roots and 36,298 more specifics. The comparison table is shown in Table 4.

| Jan-17 | Jan-18 | Delta | Unchanged | Re-Home | Removed | Added | |

| Announcements | 646,059 | 698,680 | 52,621 | 557,812 | 17,336 | 70,881 | 123,502 |

| Root Prefixes | 309,092 | 332,487 | 23,394 | 275,278 | 11,041 | 23,166 | 46,168 |

| Address Span (/8s) | 158.40 | 160.86 | 2.52 | 149.06 | 2.64 | 6.70 | 9.91 |

| More Specifics | 336,966 | 366,193 | 29,227 | 282,534 | 6,325 | 47,716 | 77,334 |

| Address Span (/8s) | 56.04 | 57.37 | 1.33 | 49.72 | 0.75 | 6.32 | 6.90 |

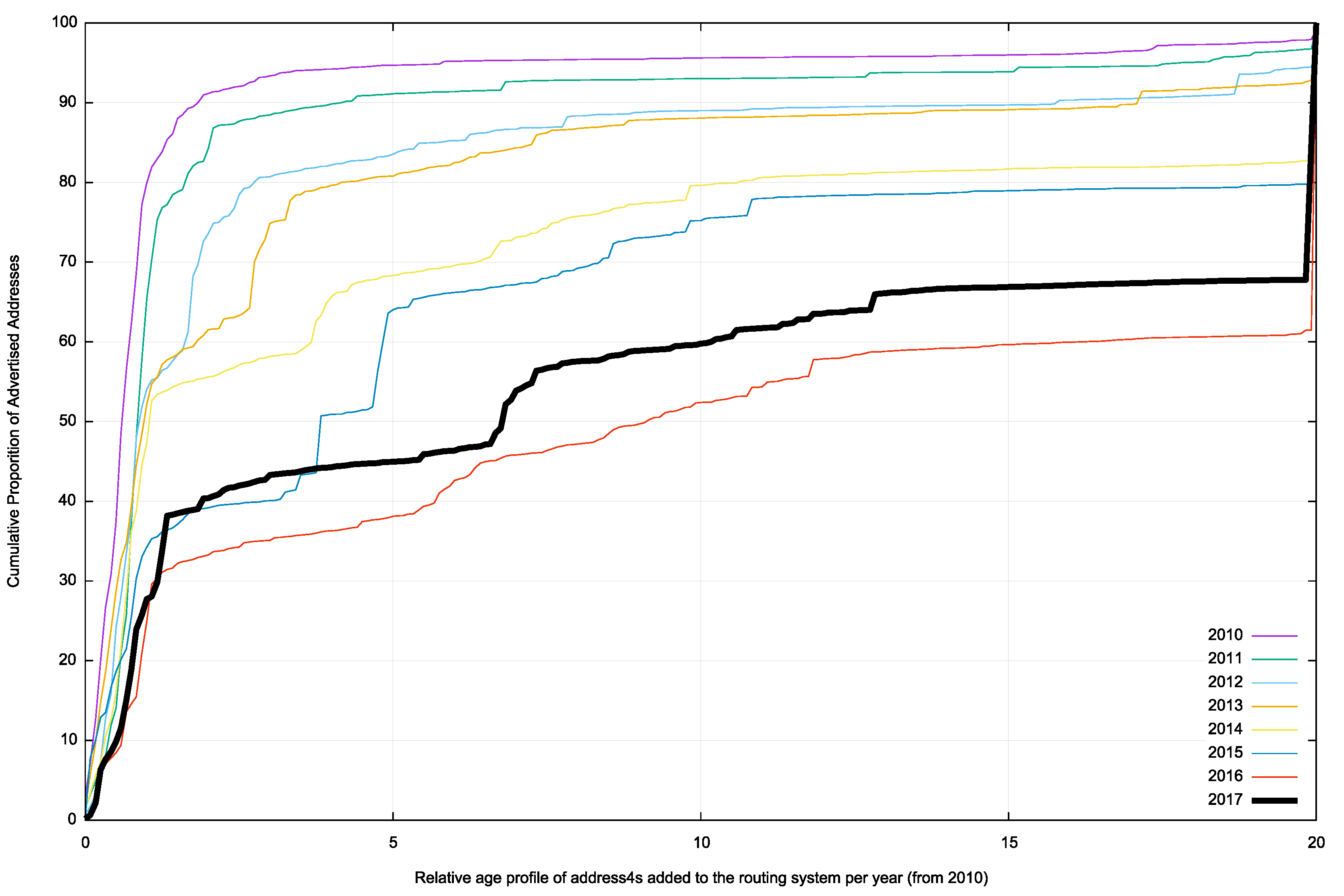

Figure 38 shows the relative age (as determined by the date of registration of the address) for addresses that were announced each year since 2010.

In 2010, 80% of all newly advertised addresses in the year were allocated in the same year. Most of the growth in advertised addresses in 2010 was from new allocations of address space. But with the onset of address exhaustion from 2011 onward, this level has dropped. In 2014, less than half of the newly advertised addresses were allocated. In 2016, this figure dropped to 30% of addresses that were added to the routing system and were drawn from the remaining unallocated address pools. Another 30% were originally allocated since 1996 or within the last 20 years. The remaining 40% were part of the early allocations that form the “legacy” address pool.

This data tends to confirm that address transfers and trading is allowing holders of otherwise idle or non-publicly used IPv4 addresses to release them for use by current network operators.

Can we reasonably expect the IPv4 address table to reach 950,000 entries in five years from now?

It is one possible scenario, but in so saying that, it also would imply this protracted transition to IPv6 will extend over the next five years. The transition has already taken such a protracted period of time that it is now quite plausible to consider a scenario where IPv4 will still be the mainstream IP protocol in 2023.

What of IPv6? What can we see in the Internet’s routing data about the prospects for IPv6?

Forecasting the IPv6 BGP Table

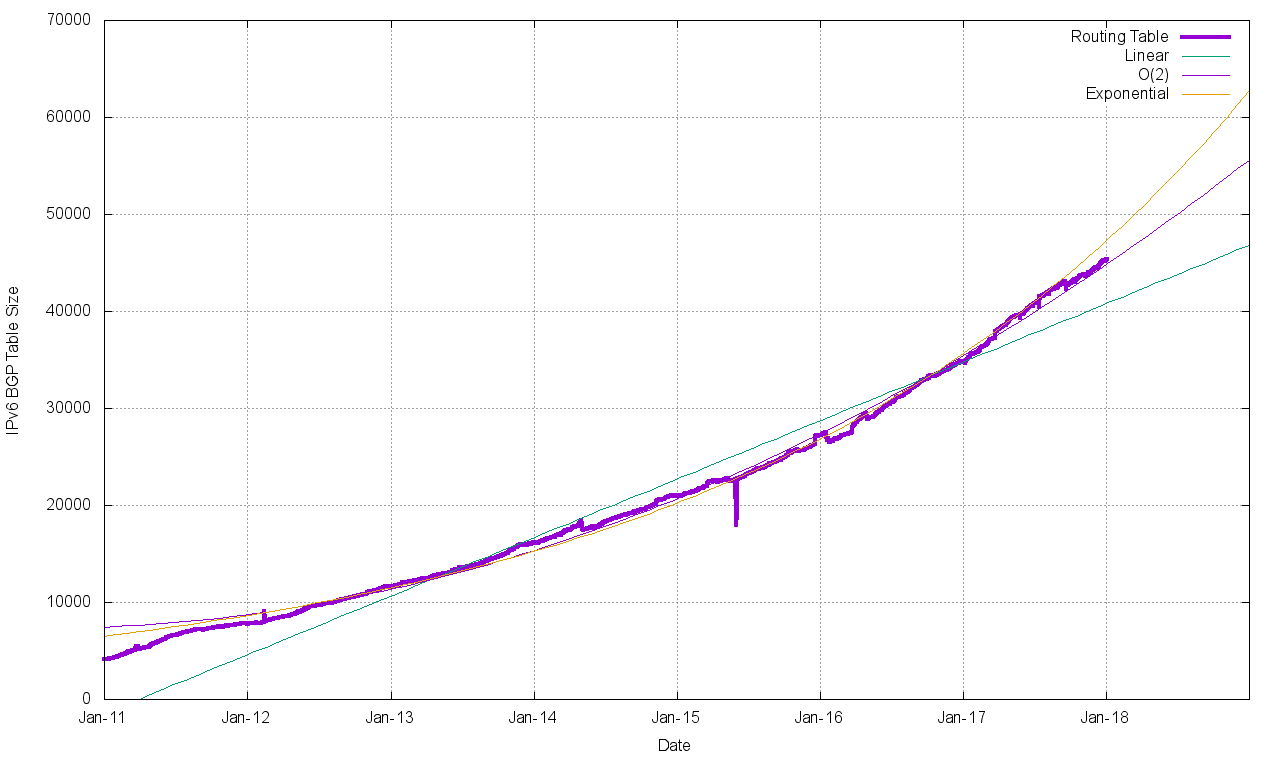

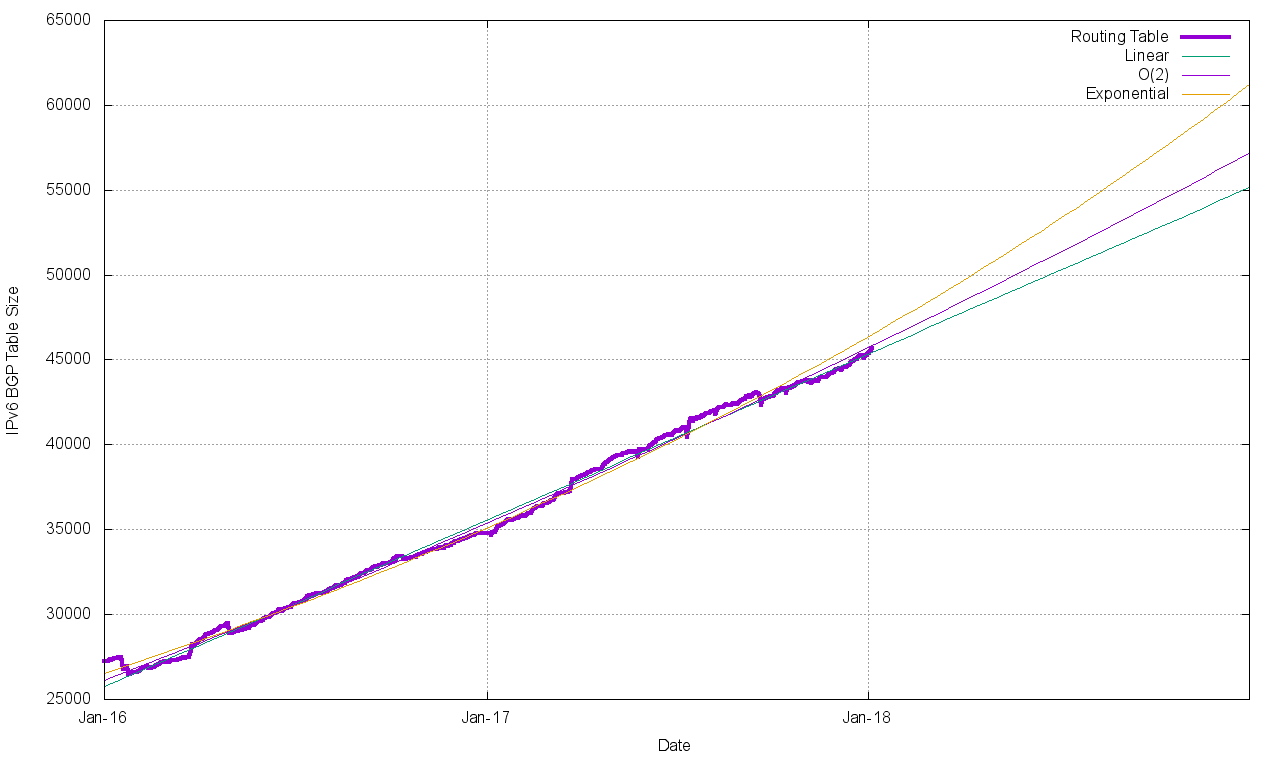

The same technique can be used for the IPv6 routing table. Figure 39 shows the data set for BGP from January 2016 until December 2017.

The first order differential, or the rate of growth of the IPv6 BGP routing table is shown in Figure 40. The number of additional routing entries has grown from 10 new entries per day at the start of 2011 to a peak of over 30 in early 2017. Obviously, this is far lower than the equivalent figure in the IPv4 domain, which is growing by some 150 new entries per day, but it does show a consistent level of increasing growth.

This implies that a linear growth model is inappropriate for modelling growth in IPv6. A better fit to the data is a compound growth model, with a doubling factor of some 24 months. It is possible to fit a linear model to the first order differential of the data, which can be used to derive an O(2) polynomial fit to the original data. The fit of a linear, O(2) polynomial and an exponential model against the data is also shown in Figure 40.

The projections for the IPv6 table size are shown in Table 5.

| IPv6 Table | IPv6 Prediction (linear) | IPv6 Prediction (exponential) | |

| Jan 2014 | 16,158 | ||

| Jan 2015 | 20,976 | ||

| Jan 2016 | 27,241 | ||

| Jan 2017 | 37,469 | ||

| Jan 2018 | 45,388 | 40,842 | 47,314 |

| Jan 2019 | 46,876 | 62,771 | |

| Jan 2020 | 52,910 | 83,278 | |

| Jan 2021 | 58,961 | 110,569 | |

| Jan 2022 | 64,995 | 146,690 | |

| Jan 2023 | 71,029 | 194,611 |

The linear and exponential projections in Table 5 provide a reasonable estimate of the low and high bounds of the growth of the IPv6 BGP routing table in the coming years. At this point these figures are not a cause for any significant concern.

If IPv6 continues to grow exponentially over the next five years, the size of the IPv6 routing table will be approaching one quarter of a million entries. In hardware terms, an IPv6 address prefix entry takes four times the memory of an IPv4 prefix, so the memory demands of the IPv6 routing table will be approaching that used by the IPv4 table at this time.

Conclusions

These predictions for the routing system are highly uncertain. The correlation between network deployments and routing advertisements has been disrupted by the hiatus in supply of IPv4 addresses, causing more recent deployments to make extensive use of various forms of address sharing technologies.

While a small number of providers have made significant progress in public IPv6 deployments for their respective customer base, the overall majority of the Internet is still exclusively using IPv4. This is despite the fact that among the small set of networks that have deployed IPv6 are some of the largest ISPs in the Internet!

The predictions as to the future profile of the routing environment for IPv4 and IPv6 that use extrapolation from historical data can only go so far in providing a coherent picture for the near-term future.

Despite this uncertainty, nothing in this routing data indicates any serious cause for alarm in the current trends of growth in the routing system. There is no evidence of the imminent collapse of BGP.

None of the metrics indicate that we are seeing such an explosive level of growth in the routing system that it will fundamentally alter the viability of carrying a full BGP routing table anytime soon. In terms of the projections of table size in the IPv4 and IPv6 networks, the BGP sky is firmly well above us, and it’s not about to fall on our heads just yet!

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Interesting, thx. 🙂