This post was co-authored by Prof Eugenia Georgiades

The world is entering a new era of connectivity. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellations have become central to how economies think about Internet access, national security, and competition. With thousands of satellites now orbiting just a few hundred kilometres above us, the LEO market is growing far faster than the laws and institutions designed to govern it.

This mismatch is significant because poorly designed regulatory frameworks can either stifle innovation or expose economies to unacceptable security risks. This post explores how different economies approach LEO satellite regulation, why these choices matter, and what a balanced, future-proof framework should look like.

The topic is further explored in our paper, ‘The Role of Regulatory Frameworks in Balancing Between National Security and Competition in LEO Satellite Market‘.

A sky full of satellites — and new challenges

LEO satellites sit roughly 160 to 2,000 kilometres from Earth, much closer than the traditional geostationary satellites. This proximity brings lower latency, higher speeds, and coverage for remote communities where terrestrial broadband is impractical.

Services like SpaceX’s Starlink, Amazon’s Kuiper, and OneWeb aim to cover the Earth with affordable, high-speed Internet. Such a market is capital-intensive, technologically complex, and increasingly crowded.

The closer satellites orbit, the higher the risk of collision. Without coordinated global rules, economies face technical, security, and economic pressures, each pushing them to regulate aggressively. The risk of cyberattacks on satellite systems raises further concerns. The LEO satellite revolution is forcing states to choose between openness to global competition and tight control for national security.

Why licensing matters more than ever

Every LEO operator must pass through a maze of domestic licensing rules before offering service. These rules determine:

- Who can provide Internet services to local users.

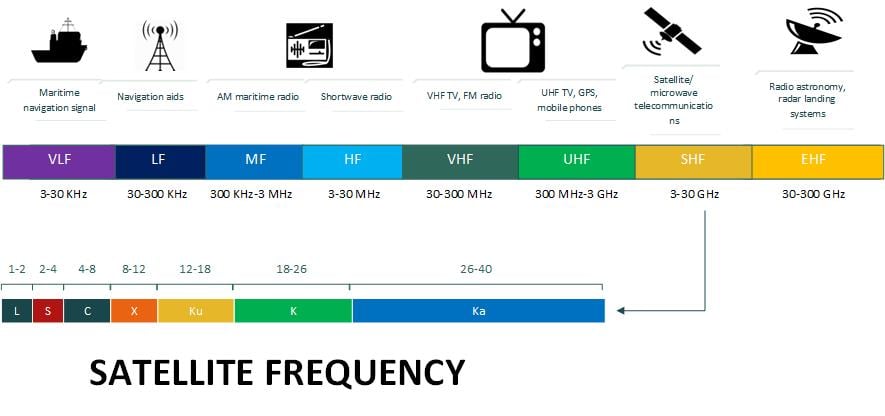

- The type of spectrum they can use.

- Whether foreign investors may participate.

- How governments will treat data, infrastructure, and supply chains.

Licensing has shifted from a simple administrative process to a powerful policy lever and a gatekeeper that balances commercial freedom with strategic caution. Depending on the economy, this gatekeeper either protects domestic businesses, militates against perceived national security threats, or fosters competition. Ideally, it should do all three without harming consumers or limiting innovation.

Articulating a national security test

From our comparative analysis of Australia, Japan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Viet Nam, two regulatory models can be extracted.

1. The national security test model

Australia and Japan place strong emphasis on the security implications of foreign investment in telecommunications infrastructure.

Any foreign investor must pass a national security assessment to prove that their operations will not compromise sovereignty, critical infrastructure, or sensitive data. Australia, for example, blocked some foreign investors from its 5G rollout and requires foreign investors to notify its Treasurer before investing in sensitive sectors like telecommunications.

The logic is simple: Satellite networks are now part of a nation’s defence posture. This model enhances state control and manages geopolitical risk. Nonetheless, it creates uncertainty, adds transaction costs, and can reduce the number of market participants, sometimes unintentionally shielding domestic incumbents from competition.

2. Unarticulated national security test

While Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Malaysia regulate licensing and spectrum tightly, they have yet to articulate a clear-cut national security test ruling the LEO satellite market. Their focus is on maintaining orderly markets, ensuring fair competition, increasing technological capacity, and attracting foreign investment.

Malaysia, for example, recently granted SpaceX 100% foreign ownership to encourage rapid infrastructure development. This openness fosters innovation and reduces prices for consumers. Despite this, without security safeguards, economies may underestimate long-term risks related to data flows, infrastructure dependence, or supply chain vulnerabilities.

The hidden costs: Transaction costs and rent-seeking

Regulations can unintentionally distort markets. When rules are complex or unpredictable, businesses adjust their behaviour not to serve customers better but to navigate bureaucracy more efficiently. Launching and maintaining LEO constellations requires huge investments. If licensing is unclear, slow, or inconsistent, these costs rise. Firms may respond by:

- Forming exclusive partnerships.

- Locking in long-term supplier contracts.

- Passing costs to consumers.

- Avoiding certain jurisdictions entirely.

This reduces competition and limits innovation, and ultimately harms users.

When regulations create monopolies or discretionary decision-making, companies may engage in lobbying or political manoeuvring to secure favourable treatment. This diverts resources away from innovation and inflates prices. Spectrum allocation is a prime area where rent-seeking thrives. As spectrum is scarce, first movers may try to capture it at the expense of rivals. A well-designed auction system can curb this behaviour; a poorly designed one can entrench it.

What a robust regulatory framework should look like

The LEO satellite market is too important to be governed by outdated systems. A forward-looking regulatory model should:

- Support competition: Open, transparent licensing processes ensure new entrants can challenge incumbents. Consumers benefit through lower prices and better services.

- Protect national security: Governments should apply security tests in a targeted, evidence-based way. ‘National security’ should not become a catch-all excuse for shielding local firms.

- Reduce regulatory burdens: Clear guidelines, streamlined procedures, and predictable decisions lower transaction costs and encourage investment.

- Limit rent-seeking activities: Spectrum auctions, clear licensing rules, and independent oversight reduce opportunities for political or economic manipulation.

- Foster international cooperation: Satellites do not recognize borders. States should work toward shared procedures for orbital management, interference mitigation, and data security.

The path forward

The LEO satellite market offers enormous promise: Faster Internet, greater digital inclusion, economic growth, and more resilient infrastructure. Without thoughtful regulation, it could also create new forms of inequality, insecurity, and market concentration. The best regulatory frameworks will not simply choose between national security and competition but seek to harmonize them. Doing so will ensure that as we fill the skies with satellites, we do not let innovation outpace the institutions meant to guide it.

Read our paper, ‘The Role of Regulatory Frameworks in Balancing Between National Security and Competition in LEO Satellite Market‘ for a more comprehensive exploration of this topic. This post and paper build on work we did with the APNIC Foundation.

Eugenia Georgiades is an Associate Professor at the School of Law and Justice, University of Southern Queensland.

Dr Martin Pedram holds positions as a Research Assistant on the space project at Bond University and as a Carl Menger Fellow at the Mercatus Center.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.