Ever wondered if a massive explosion in the sun could impact your Internet connectivity?

It’s not science fiction. When a solar storm hits Earth, it can have real-world consequences, and satellite networks like Starlink are on the front lines.

But how does this happen? What is a solar storm, and how does it interfere with your Internet? To draw a clear perspective, let’s start with space weather.

What is space weather?

The space weather near Earth is mainly driven by the Sun. The Sun continuously emits a stream of charged particles (protons, electrons, and so on), or plasma, known as the solar wind. Occasionally, a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) — a massive eruption from the Sun — can release extreme ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, or a burst of dense, hot, high-velocity plasma into outer space, often carrying strong electromagnetic fields (see Figure 1).

Sometimes, our planet falls in the pathway of such a solar eruption, and radiation shock waves sweep through, causing disturbances in Earth’s magnetic field known as a ‘geomagnetic storm’. When the intensity of these disturbances falls approximately below –350 nanotesla (nT), the event is considered a ‘superstorm’.

In May 2024, Earth was hit by such a superstorm. See the animated Video 1, which demonstrates how multiple solar eruptions on 8 May 2024 smashed into our Earth on 11 May 2024 at 800 kilometres per second (km/s). That led to the May 2024 solar superstorm, which reached a peak intensity of –412nT.

How a solar storm hits a satellite

Starlink satellites are deployed in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The majority are orbiting Earth at an altitude of 500km to 600km, where the atmosphere is very thin, almost negligible.

During extreme space weather events, the interaction of charged particles from the Sun heats the upper atmosphere (thermosphere and exosphere) and causes it to expand, sometimes by as much as 100km. Therefore, a satellite designed for a thin atmosphere suddenly experiences a thicker layer of atmosphere, which causes much higher drag (atmospheric friction).

We at the Department of Computer Science & Engineering, IIT Kanpur, developed a data-driven, open-source tool called CosmicDance to analyse such events at scale. CosmicDance ingests publicly available, real-world solar radiation intensity and satellite trajectory datasets and generates insights on satellite trajectory changes that took place shortly after solar events.

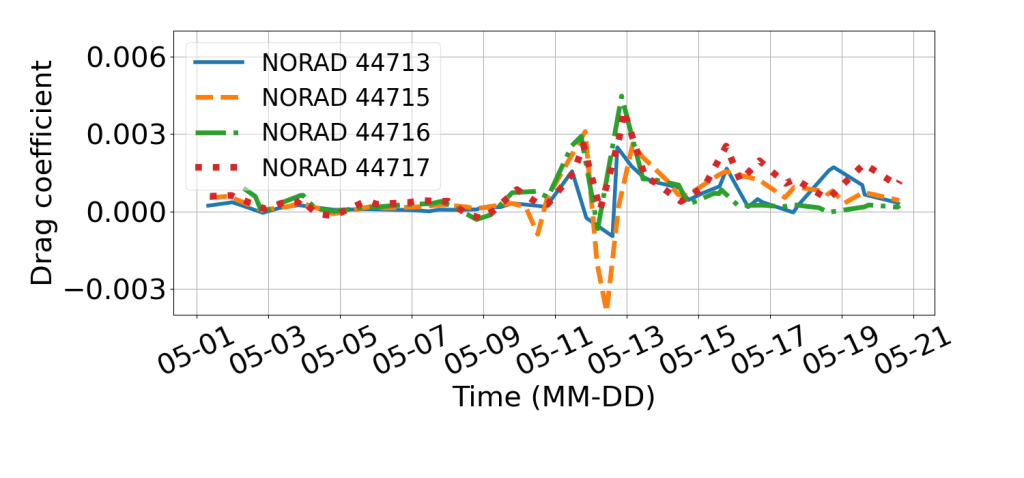

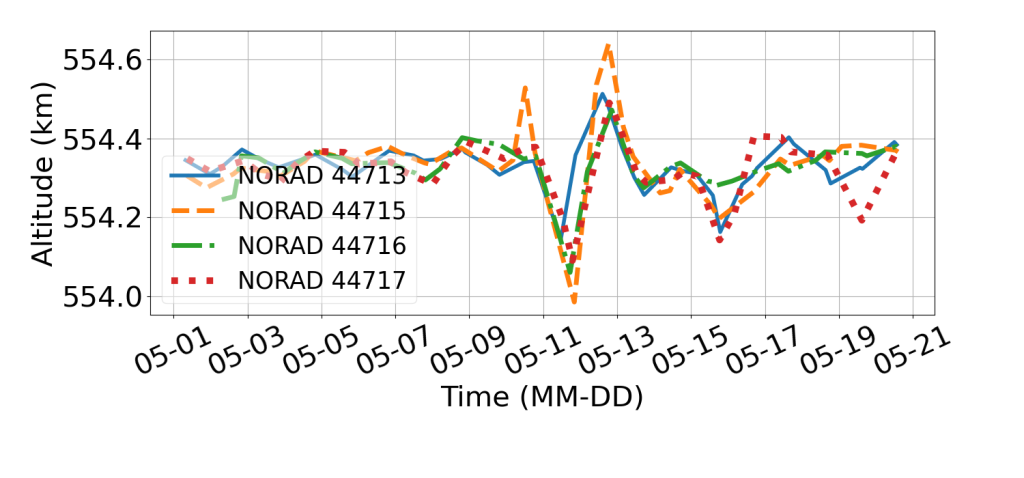

Using this tool, we show in Figures 2 and 3 how Starlink satellites reacted. We picked five Starlink satellites and plotted their orbital drag (Figure 2) and altitude (Figure 3). Notice that after the superstorm’s commencement on 11 May 2024, at 2:00 UTC, the satellites began experiencing 3-5X more drag than their baselines. As a result, the satellites started losing altitude by a few 100 metres.

To countermeasure this orbital decay, Starlink satellites likely initiated station-keeping manoeuvres. Notice that the orbital drag falls below zero as the satellites start gaining altitude. Later, Starlink, in their report to the FCC, mentioned that the satellite propulsion system kicked in ‘in real-time’ to counter the orbital drag, which supports our observations from CosmicDance.

The implications for network connectivity

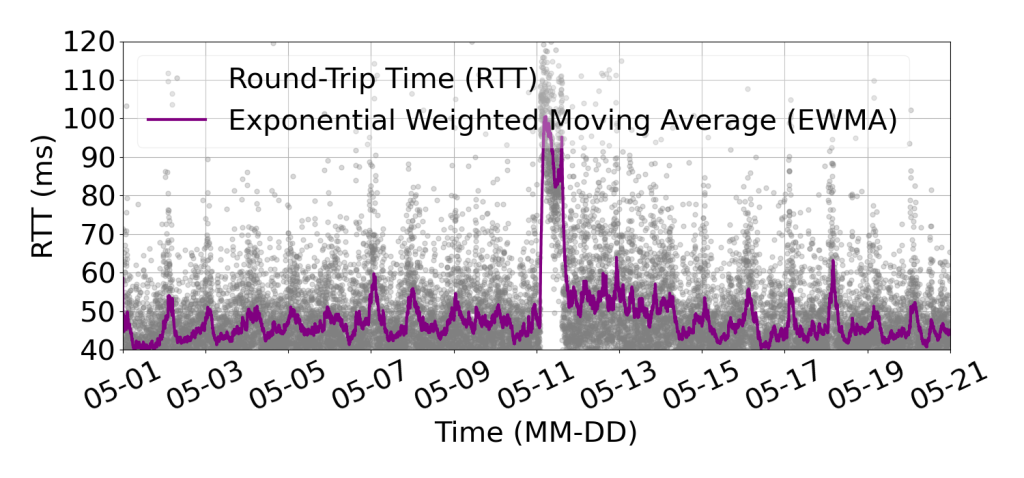

In our recent work, we investigated the implications of such events for connectivity. For this, we collected built-in periodic ping measurements from 96 RIPE Atlas probes connected to Starlink’s Autonomous System Number (ASN 14593), located across 24 economies.

We found that many probes experienced spikes in packet loss and increased Round-Trip Time (RTT) during the May 2024 solar superstorm. For instance, notice the RTT from probe ID 62741 in Colorado, US (Figure 4), where the recorded RTT during the superstorm was above 100ms — more than 2X the 40 to 60ms on usual days.

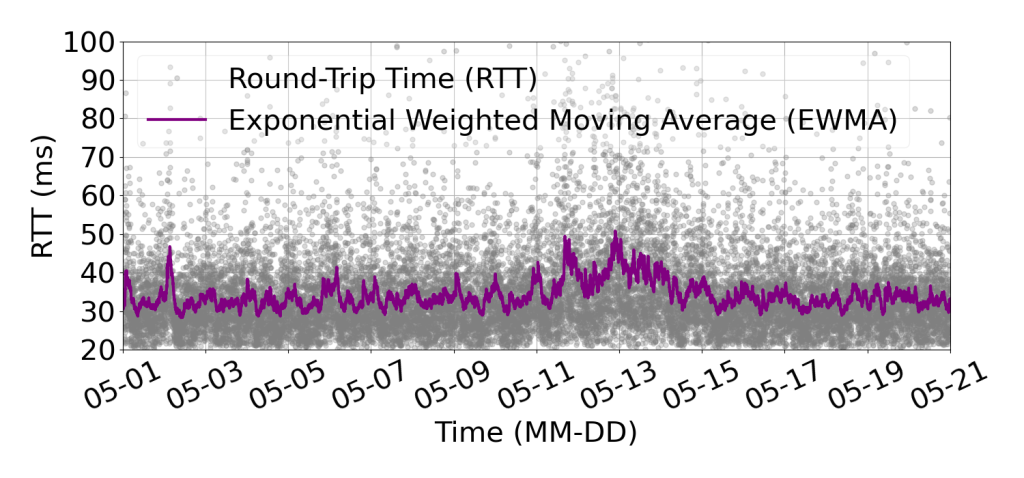

However, now notice the RTT from probe ID 61081 in North Carolina, US (Figure 5), where the recorded RTT during the superstorm shows only a slight inflation compared to other days, indicating a less severe impact.

Key takeaways

Our key observations provide evidence of the connectivity implications for LEO networks during geomagnetic storms. The magnitude of these implications is not consistent across different regions on Earth.

Starlink’s proprietary system offers limited visibility into its network operations, preventing a deep investigation into the root cause of packet loss and RTT inflation over satellite links. It is also important to note that the available network measurement data for Starlink is skewed towards North America and Europe.

As Starlink continues its expansion to other parts of the world, and as other LEO satellite Internet providers (like Amazon’s Project Kuiper, Guowang, and OneWeb) start consumer service with significant satellite fleets, future research will likely benefit from more geo-diverse datasets. This will enable much more in-depth investigations into the resilience of our growing space-based Internet infrastructure.

For more details on the study, read our paper ‘An investigation of Starlink’s performance during the May ’24 solar superstorm’.

Suvam Basak is a PhD student at IIT Kanpur. His research interests lie in the simulation and evaluation of LEO satellites’ connectivity.

Amitangshu Pal and Debopam Bhattacherjee contributed to this work.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.