Around a decade ago, I proudly joined the — then still small — ranks of people in New Zealand with a solar photovoltaics system on their roof. Ours even had a battery, meaning we had an uninterruptible power supply in case of power outages. A fire in a cable trench at the local network company a few months after installation left us as the only house in the suburb with lights and Internet on, and the odd refugee steak from neighbours’ thawing freezers in ours. So far, so good.

Sometime not long after the installation, the need arose to make configuration changes on our ADSL router. This proved to be a painful exercise, with the router’s web interface being slow to respond, and odd effects seen in terms of data saved and router behaviour in general. Clearly, that baby was on its way out.

So off to the local computer store to buy a new one. Not level entry, but one that had decent dual-band Wi-Fi, from a well-known brand. Once back home and unboxed, the new thing got connected to the network in place of its predecessor, and I set upon configuring the beast. And a beast it proved to be. Just as slow and bucking as the old one in fact.

First theory: Maybe it’s something on the network. So out go all RJ-45 connectors except the direct line to the configuring laptop. The problem persists.

Next theory: I got the runt of the litter. So back to the shop to claim a warranty, where they asked me to demonstrate the problem to them. Of course, it’s not replicable. So, I pull my tail in and slouch back home, just to find the problematic behaviour continues as before.

The only factor I could think of that was different between the home and the shop was that the power supply in the shop was genuine grid mains. Mine came off a professionally chosen and installed 4500W peak solar sinewave inverter deemed fit for the job by the local lines company (from whom we were leasing the system).

But not all our power outlets were solar inverter supplied — some still connected straight to the grid. Out came my trusty old extension lead and I connected the new router to it. Lo and behold, it now behaved itself. Back onto the solar-supplied socket, and back were the problems. Aha!

The fix: Rummaging through my old parts box unearthed a power supply that was a bit more powerful than the one that came with the router, and even fit the connector. Lesson learned.

Fast forward almost a decade. My PhD student Wayne Reiher sits in Tarawa (Kiribati) to implement an ISIF Asia-funded project.

We’d tested and preconfigured pretty much all the components Wayne is deploying in Auckland before sending them to Tarawa, including the router that he’s now having a problem with. Wayne’s an old hand at doing this, so he reports that he’s found an issue and fixed it. The next day, something else stops working. Another wild goose chase. The day after, yet another thing that worked perfectly the day before on the router is causing trouble. We’re a little stressed as weeks of rain and several longish power outages have already delayed our schedule.

This is the last thing we need. But I get a sense of déjà vu. Clearly, we can’t expect perfectly clean power in a place like Tarawa. The router is from the same manufacturer as the one that caused me all the trouble ten years ago. I grab the reference unit (same router model) from our lab and take it home, with a brief detour to an electronics store along the way to grab a few connectors and a couple of capacitors.

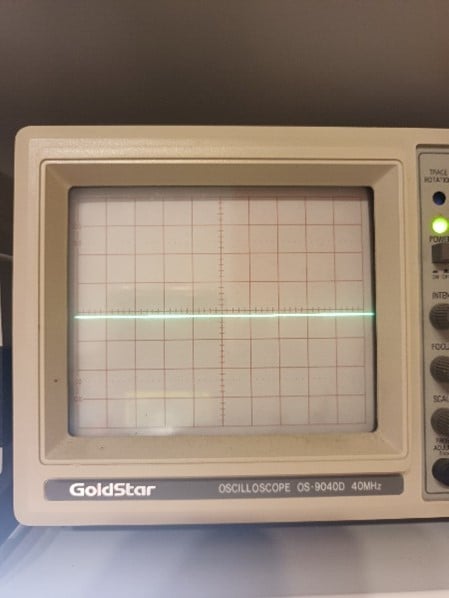

At home, I turn on my trusty old oscilloscope and build a measurement adapter to insert into the DC line between the power supply and router. And this is what I see when I look at the voltage on the measurement adapter:

Ideally, we’d just want to see a horizontal line here. But what we’re also seeing here is a significant dip in the voltage. Clearly, the router is pulling more current during the dip than the power supply on my solar circuit can supply.

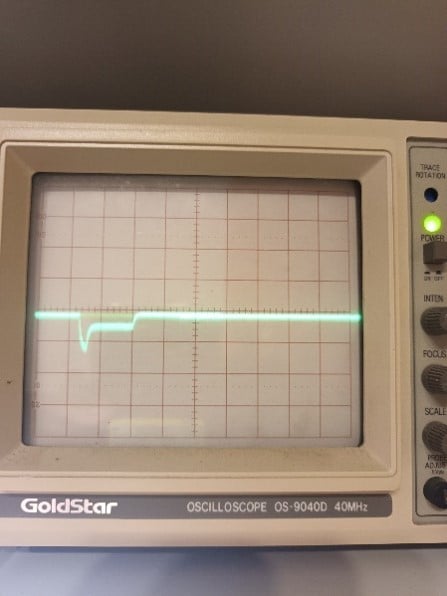

Next step: Furnish an adapter with capacitors to act as ‘shock absorbers’. The scope now shows what we want to see:

No dips, no ripples. Ideally, we’d want manufacturers to put capacitance to that effect into their router power supplies or at least routers. But we realise that capacitors cost a few cents each and aren’t really required on stable grid supplies. And manufacturing costs matter.

We’ve recently replaced our Tarawa router with a sturdier one, with an extra sturdy power supply, and a filter in the DC line like the one used here. No problems now.

So next time your router configuration plays up, consider your power supply. You may not be as dumb as you thought you were!

Dr Ulrich Speidel is a senior lecturer in Computer Science at the University of Auckland with research interests in fundamental and applied problems in data communications, information theory, signal processing and information measurement.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Just a capacitor? I’d go with a proper LC filter.

The problem may not just be a weak power supply from router (or other devices) vendors, but how good is the power provided by the inverter.

I’ve been using solar panels with a 10Kw Solax inverter, with my own DIY 80 Kwh LFP battery for more than 4 years now, and having several hundreds of devices at home, without any special power adapter or filter, all they worked well (both AC and DC powered).

I’ve done similar installations for my neighbours and some friends, and none of them had issues.

I just want to add that yes, i agree, but “Pure sinewave” is only marketing, does nothing. Power supplies can be powered by inverter generating square wave with 50/60 Hz and they will work fine.

Had similar issue but with cable TV settop box,

so my mothers tv was behaving strangely, turning picture off at random times, a was troubleshoting everything imaginable, replaced HDMI cable, did reset devices, used another TV…. then i swapped power supply for one from my wifi router (both 9V) and settop box started to work properly.

after of week of working properly i went to operator to replace “bad” power supply with “good one”, they laughed at me, of course i was for them just “another mad person” as one person called me behind my back thinking i was not hearing that.., then after half a hour, of back and forth they pretended to replace my power supply for another unit …

but because i marked it with UV only visible marker i saw it was same i gave them, …

I think what happened was that settop box did not had enough power to process image / send HDMI signals but it had enough power somehow to look operational on operators “management & monitoring” they used to “be informed” of health of devices on their network and what channels we watch on those devices…

So bought another power supply and settop box is working for 2+ years no problem.