RIPE held a community meeting in May in Rotterdam. There were a number of presentations that sparked my interest, but rather than write my impressions in a single lengthy note, I thought I would just take a couple of topics and use a shorter, and hopefully more readable bite-sized format.

Here’s the second of these bite-sized notes from the RIPE 86 meeting, on the topic of time.

A little-appreciated aspect of our digital infrastructure is just how dependent we are on access to the time. Disrupting the time base can not only lead to disruption in communications but can also result in various forms of compromise of the integrity of communications.

Accurate time was all but unobtainable for centuries, and then, as we spent significant sums in devising even more accurate timekeeping instruments, accurate time became a specialized service. All this changed when we entered a new phase of accessibility to accurate time with the use of space-based time sources with the GPS (US), GLONASS (RU), Galileo (EU) and BeiDou (CN) satellite constellations. Now highly stable accurate time is as simple as using a low-cost receiver that can receive one of these reference time signals.

However, these satellite time systems are easily jammed or even spoofed, so the exclusive use of these satellite services as a source of time is not exactly resilient against disruption. If reliable access to accurate time is important to the resilience of an economy’s digital infrastructure, then it’s just not enough to rely on satellite-based time as the only source of time.

What if an economy determined that access to reliable and accurate time was an essential component of critical infrastructure? If you were rich enough then you could launch your own space-based time source, but the issues of signal interference remain. You might also want to consider a terrestrial approach by operating your own collection of caesium clocks and using a secured variant of the Network Time Protocol’s (NTP’s) Network Time Security (NTS) to distribute this time source over the Internet. This is what has happened in Sweden.

In a presentation at RIPE 86, Netnod’s Karin Ahl described their experience in building and operating a network service that provides a reference time source (PDF).

Using a funding model partly based on a levy imposed on domestic communication service operators and partly from government funds, Netnod operates a secure and resilient time infrastructure for Sweden. Their secure time service uses caesium clock sources and distributes the time signal over NTS. The time service is available at various levels of price and accuracy, from a free service that operates within 1ms accuracy bounds to a more highly engineered service that guarantees 30µs accuracy to the UTC reference.

Many economies have invested in atomic clocks over the years as part of their national standards programs, but not many of them have elected to fold an online reference time distribution service into that program. As this Netnod presentation notes, operating a large-scale time distribution service is challenging. Such a program demands a high level of specialized expertise, stable and committed infrastructure investment in both hosting and distribution of the time signal, and cooperation across a broad collection of stakeholders.

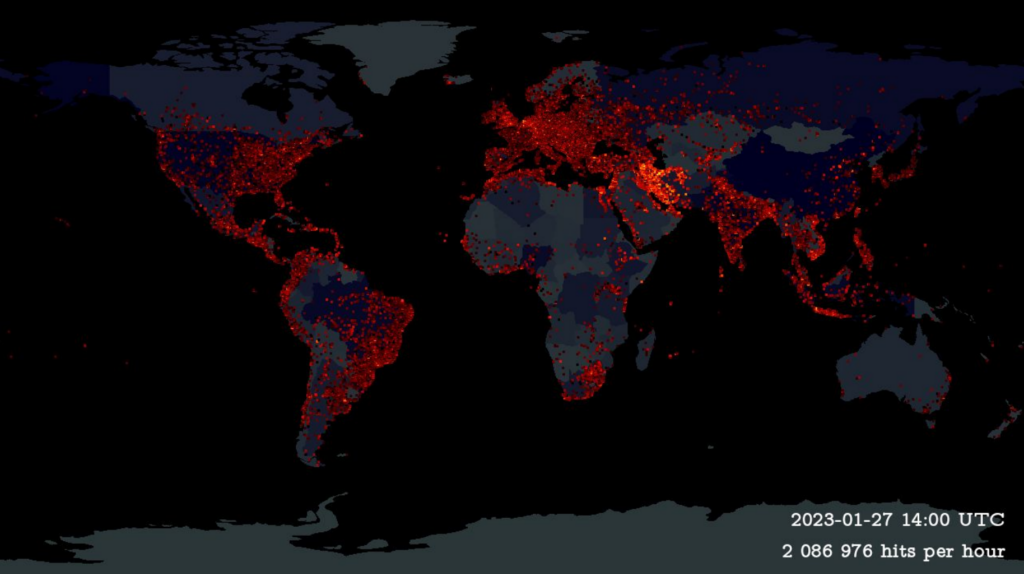

This Swedish service is not only a national time service for Sweden, but an Internet-wide secure time service. Netnod’s NTS servers were commissioned in February 2022 and started out with little fanfare or attention. They were seeing around 1,000 to 2,000 hits per hour for the first eight months, and then usage rapidly expanded. By the end of January 2023, they were experiencing some 2M hits per hour, drawn from all over the Internet (Figure 1), representing a thousand-fold increase in use within a three-month period. If you build it, then they will come!

Where does time come from?

Tony Finch presented (PDF) an amusing additional comment as a postscript to this Netnod presentation, looking at the question of where does reference time come from?

NTP, and its secured variant NTS, relay the time from a reference source (a so-called ‘stratum-1’ time source) to a client device. The NTP framework uses a hierarchy of clock sources to ensure that the time can be distributed in a scalable manner and still provide the client with a stable reference clock.

An accurate clock signal has two parts — a highly stable tick to count the passing of each time interval and an absolute base time. It appears that there is a high level of use of the GPS satellite network to provide a stratum-1 reference clock signal, and this signal can be used to manage your local oscillator to operate a local tick that is in sync with the external signal. It also provides a reference UTC time.

So where does GPS get its time source from? Evidently, this reference time signal for UTC time for the GPS satellite constellation is provided by the clocks operated at the Schriever Space Force Base in Colorado in the US. And where do the atomic clocks at Schriever get their reference time from? They apparently pull their time from the alternate master clocks operated at the US Naval Observatory. Where does the US Naval Observatory get its time source from?

Well, to answer this we need to make an excursion into the definition of the units of time. Historically, we used the Earth itself as the source of time. One day was the interval of time for the Earth to rotate once about its axis. This interval was further subdivided into hours, minutes, and seconds of course. But if the definition of a second is 1 /86,400 of the period for the Earth to rotate once about its axis, then this definition has a problem.

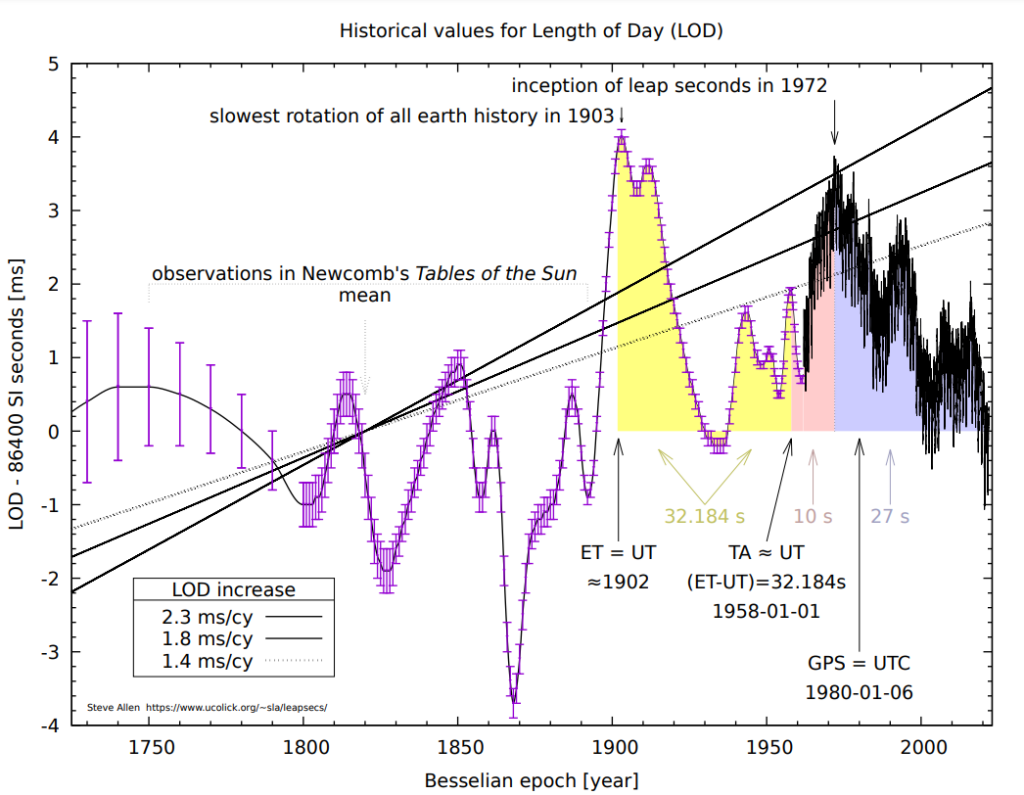

The Earth slows down as a result of the tidal forces from the moon (tidal deceleration) so the length of a day increased by 2.3ms per day, per century. But that’s not the only influence on the speed of rotation of the Earth. There is the periodic long-term climate variation associated with the ice ages and the distribution of continental plates on the Earth’s surface. As we improved in the precision of astronomical observation and also improved in the precision of timekeeping devices, these extremely small variations in the angular velocity of the Earth impact the very definition of the basic unit of time itself.

What we’ve been able to calculate is that if we used an independent constant definition of time that did not relate to the Earth’s rotation then the time period of the length of a day varies year by year (Figure 2).

So, if the Earth’s rotational speed is constantly changing then how can we define a second in a way that is constant? This was a question first addressed by astronomers and then by physicists.

Today, we use a standard definition of a second from the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) to define the clock tick, where an International System of Units (SI) standard second is equal to the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the unperturbed ground state of the caesium-133 atom.

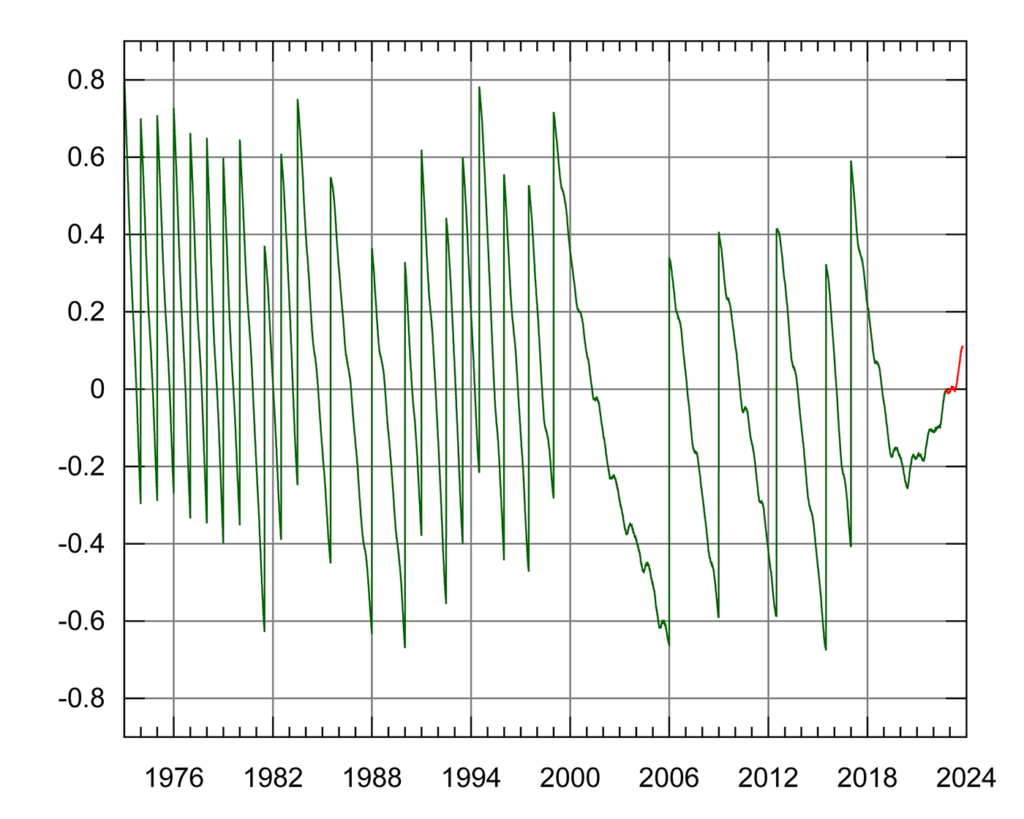

But what to do about the absolute base time? We could either let the clocks run true and redefine a ‘day’ as 86,400 SI seconds, in which case this atomic standard time (UT1) would likely differ from some rotation-related time by a full hour after 1,000 years, assuming a continuing slowing of the Earth’s rotation about its axis. Or we could keep on adjusting the UTC time signal to align it to the Earth’s rotation by inserting a so-called leap second periodically.

There are two possible time windows for this leap second, namely in the final minutes of June and December, where this minute could be extended by one second. These leap seconds are scheduled into the UTC time stream on an as-needed basis to keep UTC within 0.9 seconds of UT1. So far, since 1972, some 27 such leap seconds have been added to UTC (Figure 3). In theory, negative leap seconds could be inserted into the UTC time stream if the Earth’s rotation accelerates, again to ensure that UTC and UT1 differ by no more than 0.9 seconds.

Who schedules these periodic leap seconds to be inserted into the UTC time stream? That’s the role of the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) Centre, located at the Paris Observatory.

In today’s digital world, these leap seconds have been a nightmare. Many software systems that make use of time make implicit assumptions about the use of time. If you schedule an alarm for 86,400 seconds into the future, then that alarm will fire off tomorrow, not today. And very occasionally, instead of having the seconds value of the time of day be somewhere in the range of 0 to 59, the seconds counter will hit 60.

This has caused its fair share of system mayhem over the years, where programs would start uncontrolled loops or completely crash. And don’t forget that many of these events were happening on 31 December, perhaps the least attended time of the entire year. We have absolutely no experience with a negative leap second (with its 59-second minute) so far, and there is a considerable level of reluctance to try it. We’re just not sure how much of our digital world would crash as a result!

The coordination of UTC time and the question of leap seconds falls under the remit of the ITU-R and the World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC). Within this body, the entire question of the future of UTC and leap seconds has been considered for many years.

At the colloquium held by the ITU WP 7A SRG in May 2003, it was decided that in about the year 2022 radio time signals would stop broadcasting UTC and start to broadcast a new timescale to be called TI. The initial value of TI would match UTC, and after that, TI would increment using SI seconds with no leaps. At the time, UTC would effectively cease to exist. Fine thoughts, but it did not resolve the question.

2022 has come and gone and we are still using UTC with these irregular leap-second adjustments. At the November 2015 WRC meeting, it was decided not to decide whether UTC and the definition of the term day, will change to depend solely on the SI definition of a second or whether UTC time will continue to be related to the rotation of the Earth. The decision that they were able to make was to defer any such decision until the November 2023 meeting of the WRC.

Which is only five months away!

There are many web resources on time and leap seconds. I found Steve Allen’s material helpful, but there are many others including more writing on this topic from Tony Finch.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.