In August 1858, Queen Victoria sent the first transatlantic telegram to US President James Buchanan.

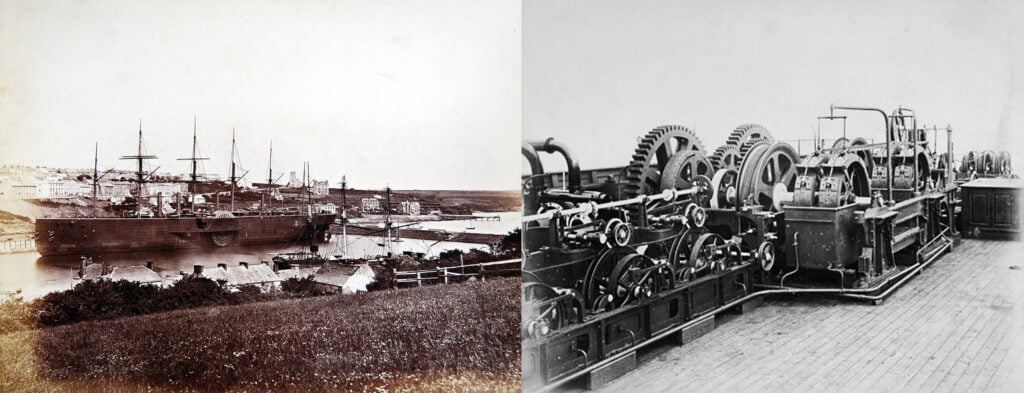

The cable system had taken a total of four years to build and used seven copper wires, wrapped in a sheath of gutta-percha, then covered with a tarred hemp wrap and then sheathed in an 18-strand wrap, each strand made of seven iron wires. It weighed 550kg per km, with a total weight of over 1.3 million kilograms. This was so heavy that it took two vessels to undertake the cable lay. The vessels met in the middle of the Atlantic, spliced the two cables together, and then set out east and west respectively. The result could hardly be described as a high-speed system, even by the telegraphic standards of the day, as Queen Victoria’s 98-word message took a total of 16 hours of attempts and retries to send.

But poor signal reception was not the only problem with the cable. The copper conductor was powered with a massive high-voltage induction coil producing several thousand volts, so enough current would be available to drive the standard electromechanical printing telegraph station (as used on inland telegraphs) at the receiving end. This, coupled with the weight and cost-saving measure of using thinner copper wires, was one important cause of the cable’s reception problems, and its imminent demise. To compensate for the deteriorating quality of the signal, the cable company’s chief engineer, Wildman Whitehouse, responded by progressively increasing the voltage applied to the cable system. In a direct current (DC) system, increasing the voltage increases the current, which raises the temperature of the copper conductor. In this case, it caused failure in the insulation, which obviously further exacerbated the deterioration of the signal. After three weeks, and just some 732 messages, the cable failed completely.

The cable company’s inquest into the failure found that Whitehouse was responsible for the cable’s failure and was dismissed. But the problems were not solely due to Whitehouse’s efforts of increasing the voltage but in poor cable construction. Not only did they use a thin copper conductor, but in places, the copper was off-centre and could easily break through the insulation when the cable was laid. A test sample was compromised with a pinprick hole that ‘lit up like a lantern’ when tested, and a large hole was burned in the insulation.

But this was not seen as a failure in the entire concept of a trans-oceanic cable. It was early proof that the concept was workable, but it needed a higher-quality implementation. It showed potential for success, and just needed some refinement. Perhaps more sensitive reception equipment, such as Thompson’s mirror galvanometer and siphon recorder. Perhaps thicker conductors and larger cable lay ships to avoid at-sea splicing with its attendant cable handling issues. Similar to the railway boom some 10 years earlier, a flurry of companies formed to lay more undersea cables that very quickly wrapped the globe.

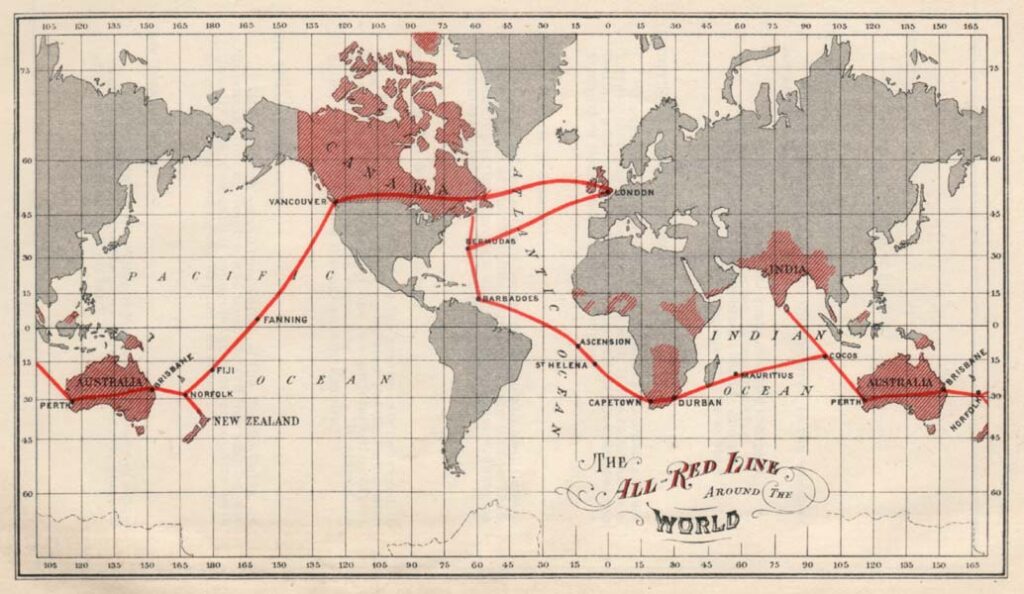

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, British-funded cables expanded eastward, into the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. An 1863 cable to Bombay (now Mumbai), India, provided a crucial link to Saudi Arabia. In 1870, Bombay was linked to London via a submarine cable in a combined operation by four cable companies, at the behest of the British government. In 1872, these four companies were combined to form the mammoth Eastern Telegraph Company, owned by John Pender. A spin-off from Eastern Telegraph Company was a second sister company, the Eastern Extension, China and Australasia Telegraph Company, commonly known simply as ‘the Extension’. In 1872, Australia was linked by cable to Bombay via Singapore and in 1876, the cable linked the British Empire from London to New Zealand.

Immediately thereafter there were a number of pressures on this burgeoning new industry to make the cables more reliable, increase the reach of the cable system, reduce the cost of messages, and at the same time, increase the speed. Development settled into a few decades of progressive refinement of the basic model, where improvements were incremental rather than meteoric. It was not until the early 20th century that message speeds on trans-Atlantic cables would exceed 120 words per minute.

In so many ways the commercial pressures for increased speed, reliability, and reach have continued to drive the cable industry for the ensuing 150 years. For many years the industry concentrated on metallic conductors for the signal, namely copper. But metallic conductors have some severe limitations. There are noise components, frequency limitations, and current limitations. So, efforts turned to fibre optic systems. The first transatlantic telephone cable to use optical fibre was TAT-8, which went into operation in 1988.

Fibre optic cables

There is a curious physical property of light that when it passes from one medium to another with a different index of refraction, some of the light will be reflected instead of being transmitted. When you look through a clear glass window you will see a faint reflection of yourself.

Depending on the angle of incidence of light meeting a refractive boundary, the proportion of reflected light can be varied. For low-incidence light, the reflection rate can approach 100% or total internal reflection. References to the original work that describe this total internal reflection property of light appear to date back to the work of Theodoric of Freiberg in the early 1300s, looking at the internal reflection of sunlight in a spherical raindrop.

The behaviour of light was rediscovered by Johannes Kepler in 1611 and again by René Descartes in 1637 who described it as a law of refraction. Christiaan Huygens, in his 1690 Treatise on Light, examined the property of a threshold angle of incidence at which the incident ray cannot penetrate the other transparent substance. Although he didn’t provide a way to calculate this critical angle, he described examples of glass-to-air and water-to-air incidence. Isaac Newton, with his 1704 corpuscular theory of light, explained light propagation more simply, and it accounted for the ordinary laws of refraction and reflection, including total internal reflection on the hypothesis that the corpuscles of light were subject to a force acting perpendicular to the interface.

In 1802, William Wollaston invented a refractometer to measure the so-called refractive powers of numerous materials. Pierre-Simon Laplace took up this work and proposed a single formula for the relative refractive index in terms of the minimum angle of incidence for total internal refraction. Augustin-Jean Fresnel came to the study of total internal reflection through his research on polarization. In 1816, Fresnel offered his first attempt at a wave-based theory of chromatic polarization. Fresnel’s theory treated the light as consisting of two perpendicularly polarized components. In 1817, he noticed that plane-polarized light seemed to be partly depolarized by total internal reflection if initially polarized at an acute angle to the plane of incidence.

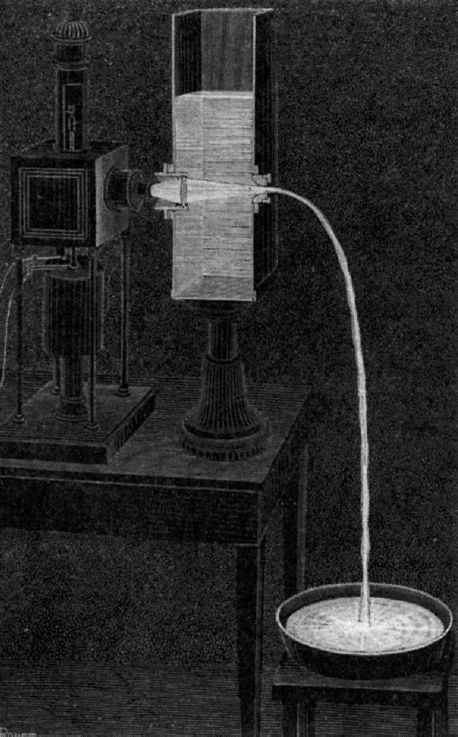

While the behaviour of total internal reflection had been useful in gaining a better understanding of the nature of light, it was still a solution in terms of a practical problem. In 1842, a Swiss physicist, Jean-Daniel Colladon, demonstrated the use of a tube of water as a waveguide for light. This was also demonstrated some 17 years later by John Tyndall in 1859. The subsequent years saw these ‘light bending’ experiments shift from columns of water to fine strands of glass (fibres).

It was not until 1930 when Heinrich Lamm invented the ‘medical endoscope’ which was a bundle of fibres carrying light into the body, and fibre endoscopes became a common tool in the medical space. Some 30 years later, in 1965, Standard Telephones and Cables (STC) turned to using guided light in the context of communications, when Manfred Borner of Telefunken in Germany patented the first fibre optic communication system. At much the same time, STC’s Sir Charles Kao offered the perspective that if a combination of glass fibre and a light source that had a loss rate of less than 20 decibels per kilometre (db/km) could be devised, then the result would be a communications system that could compete cost effectively with existing metallic conductor cable systems.

Why 20db per kilometre?

Loss is measured in decibels, which is a logarithmic unit. A loss rate of 10db per kilometre is equivalent to a degradation in the signal of 90% (1 in 10) while a loss rate of 20db is a degradation of 99% (1 in 100).

At 20db/km, a 10km fibre cable has a transmission rate of 1 in 1,020. A 40km cable has a transmission rate of 1 in 1,080. A photon may be small, but that’s still a lot of photons! By the time you try and push this 20db/km cable beyond 42km, you need to inject more photons than exist in the visible universe to get even one photon out!

In Kao’s vision, he was probably thinking about very short cable runs indeed!

In 1970, a team at Corning made a fibre that had a loss rate of 17db/km with a light source of 630nm (this 3db gain is the same as halving the attenuation of a 20db/km system). This introduction of low-loss fibre was a critical milestone in fibre optic cable development. In work on how to further reduce this loss rate, it was noted that longer wavelengths had lower rates. This led to work in the early 1970s to increase the wavelength of the light source, using near-infrared light.

There were also experiments with changing the doping agent in the fibre from titanium oxide to germanium oxide. With these two changes, using an 850nm light source (instead of 630nm) and fibre cable with germanium oxide doping, the achievable fibre loss rate dropped to less than 5db/km, which is a truly awesome change in the loss profile!

This 12db drop is a 16-fold improvement in the ‘transparency’ of the fibre. This result is close to the theoretical minimum attenuation at 850nm, and the effort is then concentrated on using light sources with even longer wavelengths. By 1976, laser light sources that operated at 1200nm had been developed that could drive fibre with an attenuation of less than 0.46db/km, and by the end of the 1970s, they were using 1550nm lasers and achieving less than 0.2db/km.

Why is 1550nm important?

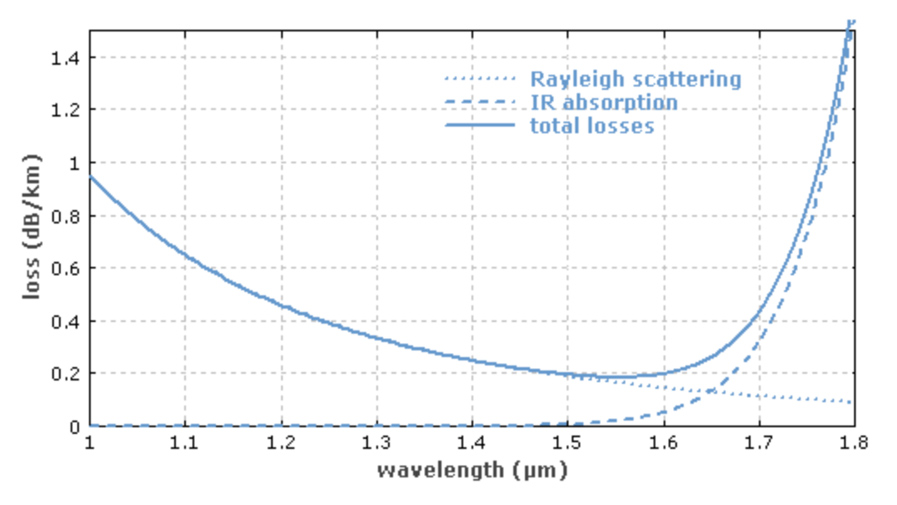

The fundamental loss limits for a silica-based glass fibre are Rayleigh scattering at short wavelengths and material absorption in the infrared part of the spectrum. A theoretical attenuation minimum for silica fibres can be predicted at a wavelength of 1550nm where the two curves cross (Figure 4). This has been one reason for laser sources and receivers work in this portion of the spectrum.

One area of refinement in recent work in germanium-doped silica-based fibre has been in reducing the water loss peak at 1383nm. Conventional single-mode fibres have a very high loss rate at this wavelength because the fibre absorbs OH− ions during manufacturing. This water loss point can continue to increase even after cable installation. The high attenuation makes transmission in this particular spectral region impractical for traditional single-mode fibres. There are two types of fibres that address this limitation: Low Water Peak (LWP) fibres, which lower the loss in the water peak band of the spectrum, and Zero Water Peak (ZWP) fibres, which eliminate the heightened loss at the water peak line.

Semiconductor lasers

A parallel thread of development has taken place in the area of semiconductor lasers.

This work can be traced back to a period of a renaissance in physics at the start of the twentieth century. In 1917, Albert Einstein described the concept of stimulated emission, where if you inject a photon of precisely the ‘right’ wavelength into a medium containing a collection of electrons that have previously been pushed into an excited state, they will be stimulated to decay back to their original stable state by emitting photons of the same wavelength of the trigger photon, and this stimulated emission will occur at the same time for all of these stimulated electrons. It took another twenty years for this theoretical conjecture to be confirmed in an experiment conducted by Rudolph Ladenburg in 1937.

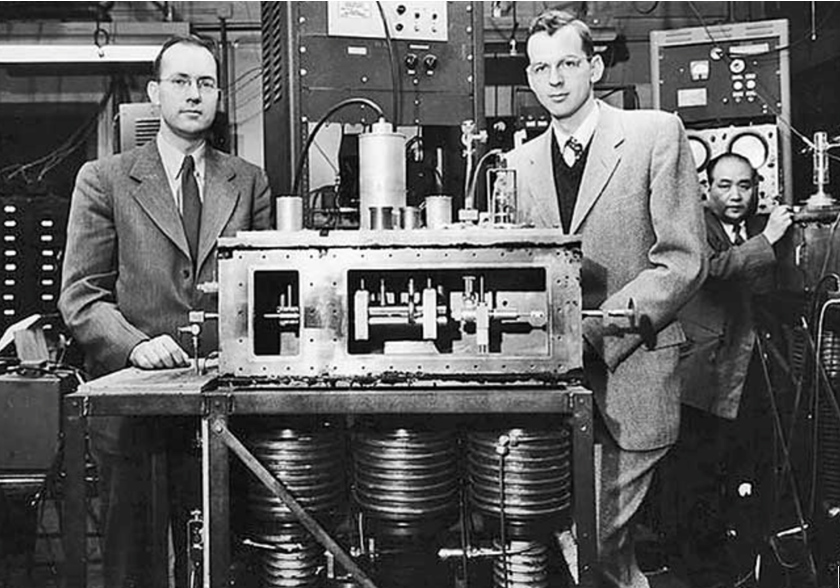

In 1947, Willis Lamb demonstrated stimulated emission in hydrogen spectra in a gaseous medium. Alfred Kastler then proposed the idea of optical pumping where shining light of a certain wavelength will push the electrons in the medium into an excited state which can then be triggered to emit stimulated emissions in a simultaneous manner. In 1951, Joseph Weber proposed the Microwave Amplifier for Stimulated Emission of Radiation (MASER), which operated at the wavelength of microwaves, with direct application for radar applications, subsequently developed in 1954 by Charles Townes (Figure 5).

In 1957, a group from Bell Labs theorized a MASER that operated at the frequencies of visible light, and they changed the name to Light Amplifier for Stimulated Emission of Radiation (LASER), which was then demonstrated by Theodore Maiman in 1960 with a pulsed ruby laser. In this experiment, the medium was a ruby crystal, and the stimulation was provided by a flashbulb. In 1962, Robert Hall proposed the use of semiconductor material as the gain medium and demonstrated the pulsed semiconductor laser.

The year 1970 brought all these ideas together into a practical device. It was a continuous operation device (rather than ‘pulsed’), that operated at room temperature (and not cooled by liquid nitrogen) and used a Gallium Arsenide semiconductor medium, demonstrated by Zhores Alferov, Izuo Hayashi, and Morton Parish. These days, the industry uses a number of alloys for semi-conductor fibre optic lasers, such as the InGaAsP semiconductor, which uses an alloy of gallium arsenide, gallium phosphide, and indium phosphide.

Further refinements

The question then became how to make this approach scale to provide a high-capacity communications system. We had seen a similar path in telephony some decades earlier when trying to place multiple conversations on a single conductor. One approach was to multiplex the conversations and use a higher common base data rate and intertwine the signals from each conversation (time division multiplexing). Another approach is to use frequency division multiplexing and encode each conversation over a different base frequency. The same applies to fibre communications.

The scaling options are to increase the data rate of the signal being encoded into light pulses, to use a number of parallel data streams and encode them into carrier beams of different wavelengths, or even to use both approaches at the same time. Which approach is more cost-effective at any time depends on the current state of lasers and fibres, and the current state of the encoding and decoding electronics (codecs) and digital signal processors. More capable signal processors allow for the denser encoding of signals into a wavelength, while more capable fibre allows for more wavelengths to be used simultaneously.

The period from 1975 to the 1990s saw a set of changes to lasers that allowed them to operate at longer wavelengths, with sufficient power to drive 10μm core fibre (single mode fibre, or SMF). These are single-mode lasers with external modulators.

The next breakthrough occurred in 1986 when work in the UK by David Payne at Southampton University and the US by Emmanuel Desurvivre at Bell Labs both discovered the Erbium Doped Fibre Amplifier (EFDA). Long fibre runs require regular amplification (or repeaters). The optical repeater model used prior to EDFA was to pass the signal through a diffraction grating to separate out the component wavelengths, send each signal to the digital signal processor to recover the original binary data, and then pass this data to a laser modulator to convert the signal to an optical signal for the next fibre leg.

Each wavelength required its own optical-electrical-optical amplifier. When a length of fibre is doped with erbium and excited with its own pumped light, then incoming signals are amplified across the spectrum of wavelengths of the original signal. Rather than demuxing the composite signal into individual signals and amplifying them separately, an EDFA system can use a single piece of doped cable in a repeater to amplify the entire composite signal.

Fibre impairments

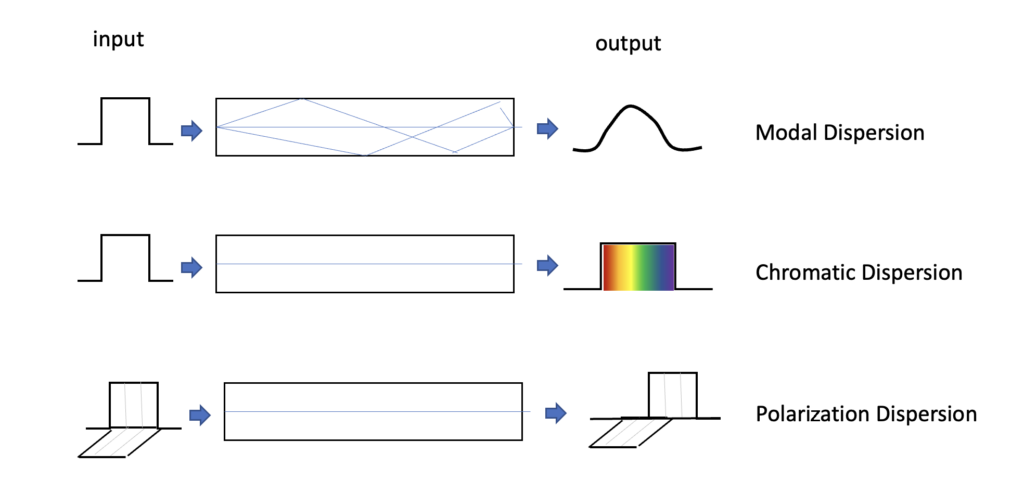

Modal dispersion

Modal dispersion is seen in multi-mode fibre. There are several paths through a large core fibre. Some paths use internal reflection off the edges of the core, while other paths are more direct without any internal reflection. The reflected paths are longer so a single square wave input pulse will be dispersed into a waveform that has a strong resemblance to a Gaussian distribution. Single-mode fibre that uses an 8-9μm core diameter does not have this form of signal impairment, because as long as the core diameter is sufficiently small, at no more than 10x the signal wavelength, the internal reflection paths are minimal compared to the path directly along the core.

Chromatic dispersion

Chromatic dispersion is due to the property that lower frequencies travel faster, and if a signal uses a broad spectrum of frequencies, then the signal will become dispersed on the transit through the fibre and the lower frequency component will arrive earlier than the higher frequency component. To reduce the level of signal degradation and increase the signal bandwidth, G.655 fibre (the most common fibre used) was engineered to have zero chromatic dispersion at 1,310nm as this was the most common laser source at the time. Signal dispersion can be compensated by placing dispersion-compensating fibre lengths in every repeater, assuming that you wanted to compensate for chromatic dispersion (which in Dense Wave Division Multiplexing (DWDM) is not necessarily the case).

Polarization mode dispersion

Silica fibre has small-scale radial variations, which means that different polarization components will propagate through the fibre at various speeds. This can be corrected by placing a Polarization Mode Dispersion (PMD) compensator just in front of the receiver. This is performed after the wavelength splitting so one unit is required for every wavelength. This requirement of PMD compensation per wavelength was an inhibitory factor in the adoption of 40Gbps per wavelength in long cable systems in DWDM systems.

These three forms of optical impairments are shown in Figure 6.

Non-linear effects

A linear effect is where the effect is proportional to power and distance, whereas non-linear effects are threshold based and only appear when a particular threshold is crossed. For linear effects, a common response to compensate is to increase the input power, but for non-linear effects, this will not necessarily provide compensation.

This was first discovered in 1875 by Jon Kerr and was named the Kerr Effect. In a light pulse, the leading part of the pulse changes in power very quickly and this rapid change causes a change in the refractive index of the medium if the optical power level is high enough. The result is that there is self-phase modulation where the pulse interferes with itself. In a Wave Division Multiplexed (WDM) system there is also crosstalk modulation, where the signals (pulses) in one wavelength interfere with the signals in other wavelengths.

There is also four-wave mixing where two wavelengths of sufficiently high power levels create two phantom side signals spaced equally apart, which will interfere with adjacent signals in a DWDM configuration.

The conventional approach to these non-linear effects was to limit the optical launch power (which limits the reach, or inter-amplifier distance in a cable run), and also to use a cable with high levels of chromatic dispersion (so that the pulse energy is dispersed by chromatic dispersion effects) and to use a large effective core area in the fibre, both of which were properties of G.652 fibre.

In the search for longer reach and higher capacity of optical systems, a new set of non-linear mitigations has been devised, which include Nyquist subcarriers, Soft Decision Forward Error Correcting codes, and Super-Gaussian PCS and non-linear compensation. All these techniques rely on improvements in the transceivers’ digital signal processing (DSP).

In the 1980s, the G.652 fibre systems were suited to the 1,310nm lasers that were used at the time. In the search for lower attenuation, we shifted to 1,550nm lasers, which were placed at the minimum attenuation point for the media. However, the large core area (80μm2) meant high chromatic dispersion that had to be compensated for with lengths of Dispersion Compensating Fibre (DCF), which effectively cancelled out the advantages of 1,550nm lasers.

There was a brief time when we used G.653 DSF (Dispersion Shift Compensating Fibre), which used a narrower core to shift the zero chromatic dispersion point up to 1,550nm. However, in the mid-1990s we started to use DWDM systems, and here the aim was to have some chromatic dispersion to reduce the crosstalk factors in the fibre.

Today we tend to use G.655 Non-Zero Dispersion Shift Fibre (NZDSF) that provides some level of chromatic dispersion at 1,550nm in order to reduce the crosstalk effects in DWDM systems centred around 1,550nm, with a core area of 55μm2.

The next step was G.655 Large Effect Area Fibre (LEAF) with a larger core area of 72μm2. This is a variant of G.655 with a low band dispersion area and a large effective area. This is a better configuration for single wavelength 10Gb transmission.

Coherent technology

In 2010, coherent technology was introduced. This denser form of packing signal encoding into the signal through phase and amplitude modulation was borrowed from earlier work in radio and voice digital models but was now being applied to photons with the advent of more capable DSPs that exploited ever narrower ASIC track width and higher capabilities at constant power.

The first generation of all-optical systems used simple on/off keying (OOK) of the digital signal into the light on the wire. This OOK signal encoding technique has been used for signal speeds of up to 10Gbps per lambda in a WDM system, achieved in 2000 in deployed systems. However, cables with yet higher capacity per lambda are infeasible for long cable runs due to the combination of chromatic dispersion and polarization mode dispersion.

At this point, coherent radio frequency modulation techniques were introduced into the digital signal processors used for optical signals, combined with wave division multiplexing. This was enabled by the development of improved digital signal processing (DSP) techniques borrowed from the radio domain, where receiving equipment was able to detect rapid changes in the phase of an incoming carrier signal as well as changes in amplitude and polarization.

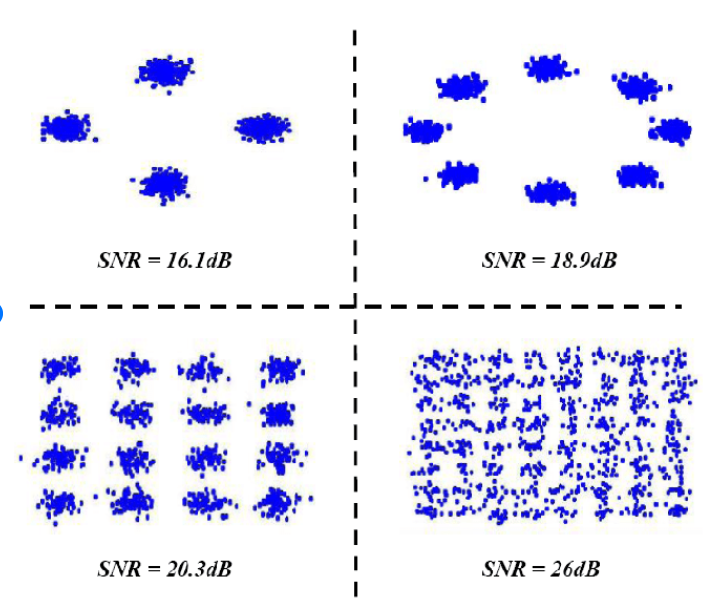

Using these DSPs, it’s possible to modulate the signal in each lambda by performing phase modulation of the signal. Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (QPSK) defines four signal points, each separated at 90-degree phase shifts, allowing two bits to be encoded in a single symbol. A combination of two-point polarization mode encoding and QPSK allows for three bits per symbol. The practical outcome is that a C-band-based 5Thz optical carriage system using QPSK and DWDM can be configured to carry a total capacity across all of its channels of some 25Tbps, assuming a reasonably good signal-to-noise ratio. The other beneficial outcome is that these extremely high speeds can be achieved with far more modest components. A 100G channel is constructed as 8 x 12.5G individual bearers.

This encoding can be further augmented with amplitude modulation. Beyond QPSK there is 8QAM that adds another four points to the QPSK encoding, adding additional phase offers of 45 degrees and at half the amplitude. 8QAM permits a group coding of three bits per symbol but requires an improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio of 4db. 16QAM defines, as its name suggests, 16 discrete points in the phase-amplitude space, which allows the encoding of four bits per symbol, at a cost of a further 3db in the minimum acceptable S/N ratio. The practical limit of increasing the number of encoding points in phase-amplitude space is the signal-to-noise ratio of the cable, as the more complex the encoding the greater the demands placed on the digital signal processor.

There are two parts to this evolution. The first is increasing the base signal rate, or baud rate. The second is to increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the system, and the third is to increase the capability of the digital signal processor. Table 1 shows the result of successive refinements to coherent fibre systems since 2010.

| Year | Mode | Baud | Capacity/Lambda | Cable Capacity | DSP |

| 2010 | PM-QPSK | 32 GBd | 100G | 8T, C-Band | 40nm |

| 2015 | PM-16QAM | 32 GBd | 200G | 19.2T, Ext C | 28nm |

| 2017 | PM-32QAM | 56 GBd | 400G | 19.2T, Ext C | 28nm |

| 2019 | PM-64QAM | 68 GBd | 600G | 38T, Ext C | 16nm |

| 2020 | PS-PM-64QAM | 100 GBd | 800G | 42T, Ext C | 7nm |

| 2022 | PCS-144QAM | 190 GBd | 2.2T | 105T, Ext C | 5nm |

The future

We are by no means near the end of the evolution of fibre optic cable systems, and ideas on how to improve the cost and performance still abound. Optical transmission capability has increased by a factor of around 100 every decade for the past three decades and while it would be foolhardy to predict that this pace of capability refinement will come to an abrupt halt, it also must be admitted that sustaining this growth will take a considerable degree of technological innovation in the coming years.

One observation is that the work so far has concentrated on getting the most we can out of a single fibre pair. The issue is that to achieve this we are running the system in a very inefficient power mode where a large proportion of the power gets converted to optical noise that we are then required to filter out. An alternative approach is to use a collection of cores within a multi-core fibre and drive each core at a far lower power level. System capacity and power efficiency can both be improved with such an approach.

The refinements of DSPs will continue, but we may see changes to the systems that inject the signal into the cable. In the same way that vectored DSL systems use pre-compensation of the injected signal in order to compensate for signal distortion in the copper loop, it may be possible to use pre-distortion in the laser drivers, or possibly even in the EDFA segments, in order to achieve even higher performance from these cable systems.

There is still much we can do in this space!

Discuss on Hacker NewsThe views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.