The evolution of the DNS name resolution environment has seen the DNS recursive resolver moving further away from the end client, with an Internet segment often being interposed between the client and the recursive resolver. The combination of an open DNS protocol and a public Internet segment between the client and their DNS resolver has been abused at various times and in various contexts for passive observation and active interception purposes.

The technical response to this situation has been the increased use of passing DNS queries over an encrypted channel between the client and the recursive resolver. The initial specification of this approach has been DNS over TLS, or DoT. Android users can enable this by adding a ‘Secure DNS’ entry in their DNS configuration, and Apple iOS users can do so by a custom configuration module. DNS over QUIC, or DoQ, has also been standardized recently, which is a packaging of DNS queries over the QUIC transport protocol. DoH takes this one step further and encapsulates the DNS query and response within an HTTP object. If the HTTPS substrate uses HTTP/2 then the underlying transport is TLS, or if it’s HTTP/3 then the transport is QUIC. DoH encompasses both transport formats.

Encrypted transport sessions have an additional setup overhead, and they become more efficient the more a single session is kept open and used for multiple queries. This is a good match for the profile of DNS transactions between a stub resolver in the client host and its primary recursive resolver.

We’d like to understand the extent to which these encrypted DNS technologies have been taken up in the public Internet. The challenge in any such measurement exercise is to gather a representative sample set that can be used as the basis for this measurement without intruding on user privacy. Query data from recursive DNS resolvers is always going to be a sensitive topic, in that such data can reveal which user is asking which DNS questions and when they are asking.

APNIC entered into a collaborative research agreement with Cloudflare over access to certain analytical data sets that relate to the use of the 1.1.1.1 DNS open recursive resolver service. While APNIC has no visibility into the details of individual user queries, we do have access to some profile information for queries that are passed to this open recursive resolver service. Part of this profile information includes the transport protocol used to convey the query to the 1.1.1.1 resolver, and that is what we will be looking at here.

Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 open recursive resolver

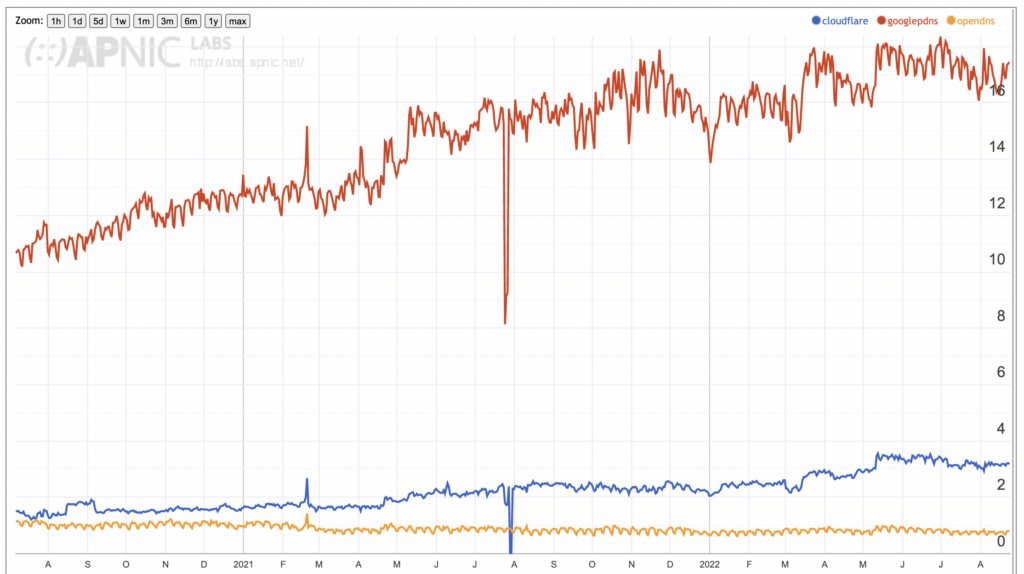

Before looking at the Cloudflare recursive resolver profile data, it’s useful to look at the market share of this Cloudflare service in the public Internet to understand the context of the transport profile data. This market share data, as measured by APNIC, is shown in Figure 1. This figure plots the ratio of users whose queries are passed to the open recursive resolvers on the first query. An estimated 17% of users currently have their queries passed to Google’s 8.8.8.8 resolver, 3% to Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 service, and under 1% to Cisco’s Open DNS service. This data points to the Cloudflare service being the second largest open DNS recursive resolver on the Internet, with a consistent growth profile over the past 24 months.

The caveat illustrated by these results is that in looking at the Cloudflare data we are looking at a relatively small proportion of users whose DNS queries have been passed through the 1.1.1.1 resolver service. This is not the default DNS resolver setting for most users, so we are looking just at those users and local networks who have altered their local configuration settings to use the 1.1.1.1 resolver, or who are using a browser application where the browser itself has been configured to bypass the local platform DNS settings and perform DNS queries directly, such as the Trusted Recursive Resolver setting in the Firefox browser. This small and potentially somewhat specialized user set has a bearing on the results that we see in this data.

Analysis of query data

The profile information APNIC assembles from the Cloudflare recursive resolver data includes the query source’s network identity (AS number), estimated economy-level geolocation of the query source, and the protocol used to pass the query to the 1.1.1.1 resolver. These numbers are aggregated into query volume buckets. Query volume is not a user count of course, and while the query count data has some relationship to user behaviour it should not be interpreted as a direct measurement of DNS behaviours per user. The protocols identified in this data set are DNS over UDP, DNS over TCP, DoT and DoH.

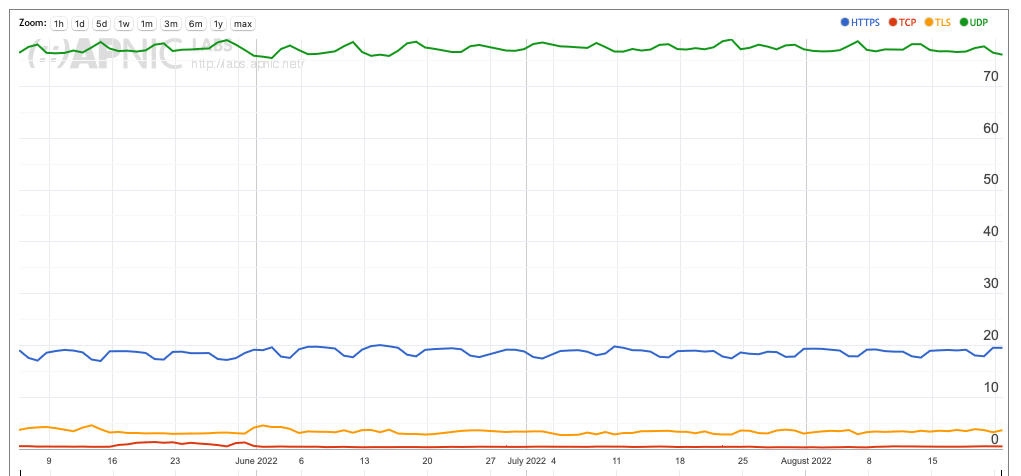

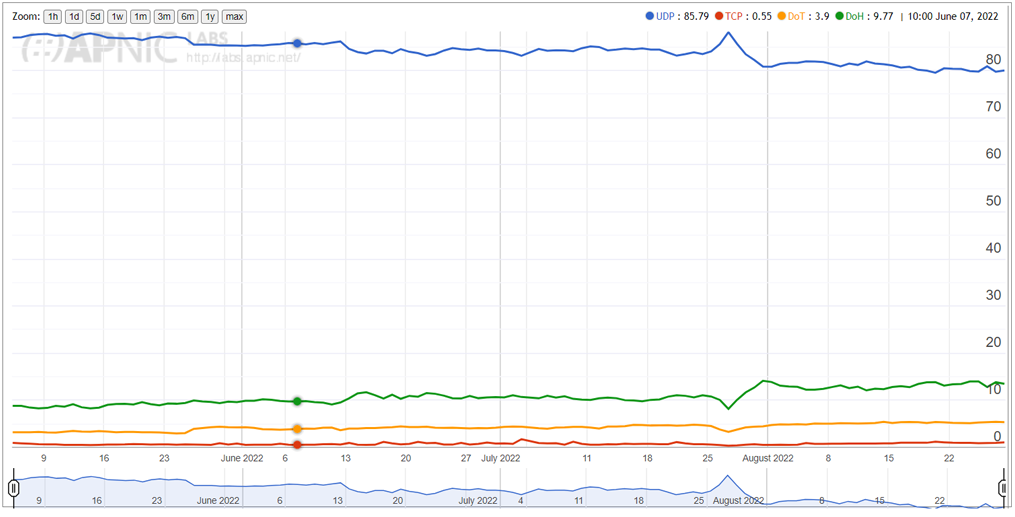

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of these transport protocols in queries used against Cloudflare’s recursive resolver service. The figure shows the day-by-day profile for the period May to August 2022.

DNS over UDP accounts for some 77% of queries seen by this open recursive resolver, and it appears that the marginal use of DNS over TCP is a direct result of large responses using the truncation bit, triggering a re-query using TCP. Given that most client resolvers do not appear to perform DNSSEC, the incidence of large DNS over UDP responses is assumed to be relatively small (we are assuming here that the major reason for large responses appears to be the inclusion of DNSSEC signature information in the response). DoH use has a pronounced weekday/weekend profile with overall use currently at a little under 20% of queries. DoT is far lower with a query ratio of slightly under 4%. In any case, having one-fifth of queries seen by this recursive resolver be presented over HTTPS is a significant observation. It’s a large enough number that it’s unlikely to be the outcome of a custom local configuration change, and more likely to be the outcome of some form of default application behaviour.

Our supposition here is that this relative preference for using DoH over DoT appears to correlate with default secure DNS settings in Chrome and Firefox browsers, which can configure the browser to use DoH to query the DNS, as compared to a platform’s DNS settings, which can configure an Android platform to use DoT to query the DNS.

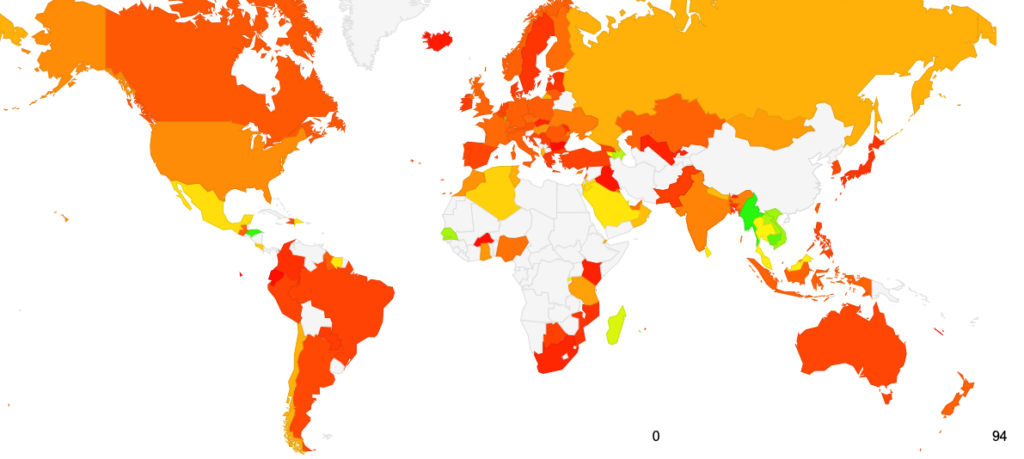

The distribution of the relative use of encrypted DNS when querying the Cloudflare resolver shows some considerable geographic variance. This is partly due to the uneven distribution of users who are clients of Cloudflare’s DNS service. Regional relative use of Cloudflare’s DNS service is highest in Northern America and Europe, where the use of encrypted DNS is also at the highest rate. In looking at individual economies, the Cloudflare-seen encrypted rates are highest in Myanmar, Honduras, Cambodia, Reunion, and Luxembourg. However, in all cases, except Luxembourg, the seen query count is extremely small in comparison to the estimated nation user population. These high numbers, therefore, may reflect a small number of individual choices as distinct from a larger general behaviour. The national profile of the use of encrypted DNS for queries as a proportion of the total query volume seen by 1.1.1.1 is shown in Figure 3.

Cloudflare’s resolver service is used most extensively in Singapore, Hong Kong, and the US. This may be the result of local use, but this may also have some relationship with some popular private relay services (such as Apple’s Private Relay service) and other forms of privacy-preserving applications where the end user’s supposed identity in terms of IP address is actually the address of the obscuring proxy service, not the end user. There are Cloudflare data centres in Singapore and Hong Kong that may serve a larger regional population, which may impact this higher intensity of use of Cloudflare’s service in these areas.

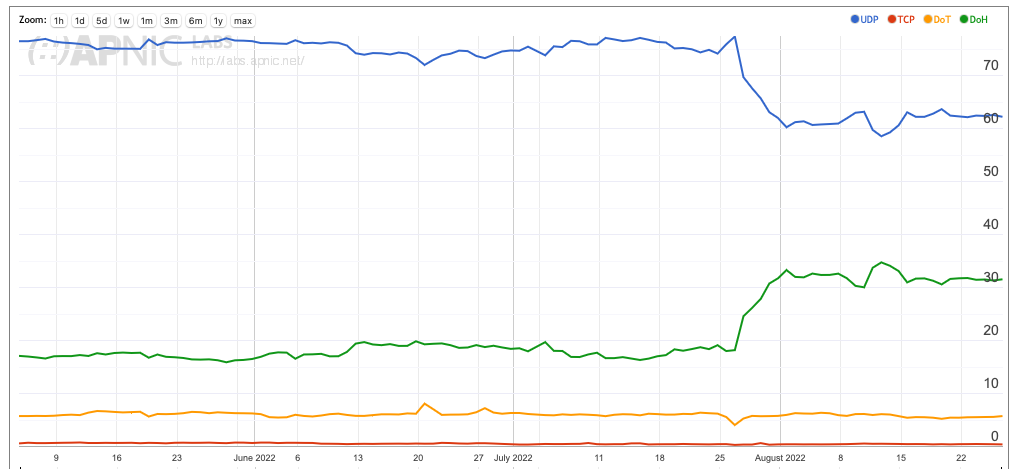

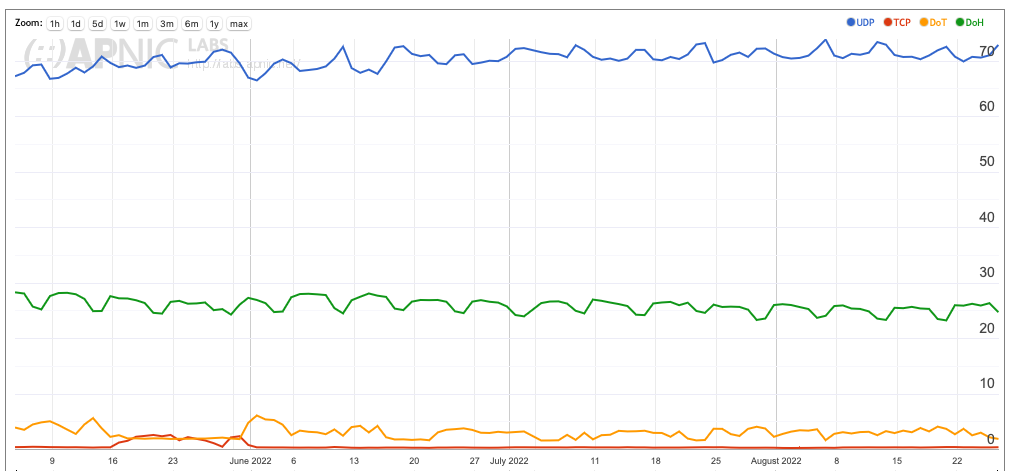

Let’s now look at a small collection of national profiles. There is extensive use of DoH in Singapore, predominately by Cloudflare’s own services (Figure 4). Some 30% of the queries seen from Singapore endpoints use DoH (Figure 4). Notable in the past two months was a marked rise in the relative use of DoH in the last week of July.

The picture in Hong Kong does not have the July discontinuity, but there is a clearly visible trend during the June – August period where the relative use of DOH and DOT is rising, while the use of DNS over UDP and TCP in the clear is dropping (Figure 5).

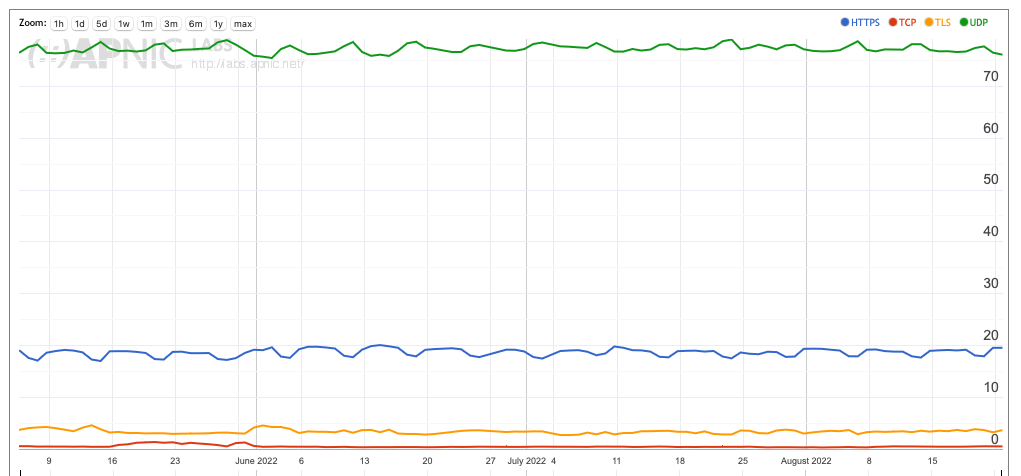

The US picture is showing a small trend in the other direction, with a small rise in the relative query volume for DNS over UDP and a matching drop in DoH rates (Figure 6).

One national environment that is dissimilar to this general use model is that of Laos PDR (Figure 7). Here a single large provider, AS9873, has a DoT-use rate of around 60%.

Neighbouring economies Myanmar, Malaysia, Viet Nam, and Cambodia also have a high encrypted DNS profile, but in those economies, the predominant protocol in use is DoH rather than DoT.

Encrypted DNS query report

APNIC Labs publishes an online report, updated daily, that reports on the DoH, DoT and DNS over UDP profiles from the Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 recursive resolver. It contains protocol profiles at the regional, economic, and at individual network levels.

Again, we should stress that this report does not necessarily reflect the broader Internet environment and the general use of encrypted queries in the DNS. Some two-thirds of the Internet’s user base uses the default DNS resolution service provided as part of their local ISP’s access service. Cloudflare’s DNS service is used by some 3% of the user base, and the user profile generated from this data stream is by no means uniformly distributed and representative of the whole.

The data indicates that Cloudflare’s DNS resolver service is predominately used as an alternative DNS resolver and not solely as a specialized provider of DoT and DoH queries. There is a component of encrypted DNS use in the data, and the relatively high use of DoH as compared to DoT suggests that this use of Cloudflare’s recursive resolver appears to be related to settings in browsers that use DoH, as distinct from platform settings that tend to use DoT.

Acknowledgements

The data on which this report is based has been provided to APNIC Labs as part of a collaborative research agreement between Cloudflare and APNIC. The data provided by Cloudflare to APNIC does not include personally identifying information, and we have not included absolute query volumes in these reports.

For APNIC Labs, Joao Damas has worked on the data platform and George Michaelson performed the data analytic processing. Geoff Huston assembled the words and pictures!

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.