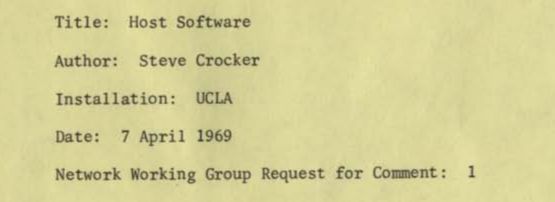

Since the first Request for Comments (RFC) memo was published in 1969, RFCs have served as a way for the Internet community to discuss methods, research, behaviours and innovations relating to the protocols that enable the Internet to operate.

Granted, in the beginning, the ‘Internet community’ was actually the ARPANET community, consisting of a distribution list of six members, as recorded in RFC 3.

7 April 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the publication of RFC 1, and it was with this milestone in mind that Darius Kazemi set out on a project to revisit some of the early net history recorded in RFCs by reading and commenting on the first 365 RFCs in order — one for every day of 2019.

Darius was motivated to undertake the project in part by his involvement in developing decentralized social networking standards, such as ActivityPub and Dat.

“I work with standards all the time and I work with people who are designing standards. I thought that it would make sense for me to read what is essentially the correspondence between the people who were standardizing the ARPANET and see if I could learn anything”, adding “also, I care a lot about how people communicate. Specifically, I was hoping to learn things about how people communicate around building a new technology”.

While you may expect that documenting 365 technical specification documents would be a daunting task, the nature of a lot of the documents are a lot less formal than one may expect, serving as proposals, plans, notices to users and meeting minutes.

“For the first few years of its existence, the RFC series was essentially a mailing list on paper from the postal service, and it was maintained by hand and by a small army of secretaries who would send copies of documents to the sites involved in the ARPANET”.

Like any mailing list, there were disagreements. In the three year period that the first 365 RFCs cover, the topic of how host naming would operate was a contentious one. Fast forward to 2019, and the Domain Name System (DNS) remains a topic of robust debate on mailing lists, at conferences, and in the pages of this blog.

Read more: DNS Wars

The ARPANET community would have to wait until RFC 114 — not coincidentally, the specification for FTP — until RFC documents would be delivered electronically over the ARPANET.

Similar, yet different

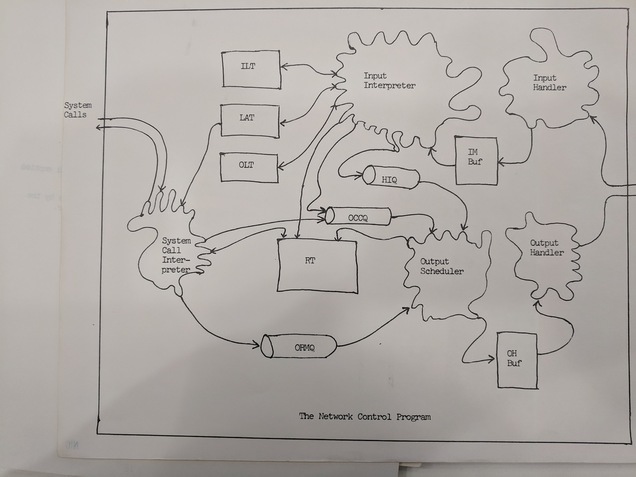

While many of the protocols laid out in these early RFCs have now been superseded (like NCP, DTP), or were never implemented at all (DEL), some have stayed with us.

“The first FTP spec in RFC 114 is pretty different from FTP today, but by 1972, the FTP spec that they had is actually pretty similar to the FTP spec today,” says Darius.

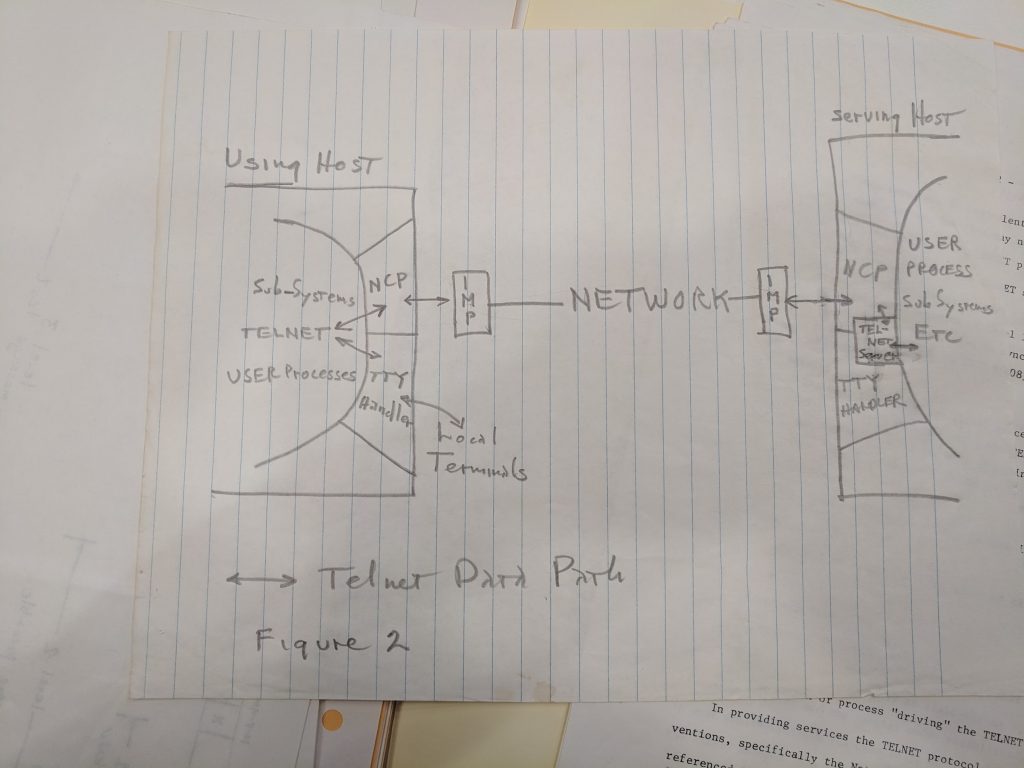

“Telnet is still basically the same. I could probably build a minimal working Telnet client from the specs as they were laid out in 1971-72”.

The FTP specification was updated in RFC 354, which introduced the status code format that formed the basis for HTTP status messages as they are used today. Darius says “the major difference is that HTTP has no 000 statuses, and 3xx means redirect in modern HTTP rather than ‘incomplete information'”.

While these RFCs cover a time before the major infrastructural protocols of today’s Internet existed (there was no IP, no TCP, no DNS and no BGP), the use of RFCs to discuss and develop internetworking standards has continued, now under the stewardship of the Internet Engineering task Force (IETF).

Forgotten elements of history

Revisiting the first few years of internetworking development also allowed Darius to unearth some elements of Internet history that are often left out of the dominant narrative. For example, commercialization of the network was an early consideration.

“People were talking about commercialization of these services basically from day one. No one knew what it would look like, but there was discussion about; do we make this a utility? Is this something that AT&T would eventually provide to people or what?”

The matter of the first message sent over the ARPANET is also not such a cut-and-dried affair either, Darius says. “People talk about the first message sent over the ARPANET from UCLA to Stanford Research Institute, but six months before that, there were messages being sent from one IMP [Interface Message Processor] to another on different sides of the country because they had to get the IMPs working before the ARPANET could work”.

While these messages weren’t sent from hosts with different hardware and operating systems like the first ARPANET message was, the milestone is still a significant one that is often overlooked.

Internet history is right there, if you want it

Since these early years, the reach and influence of RFCs have grown in step with the growth of the Internet. By the time RFC 365 was published in July 1972, the distribution list had grown to around 50 different institutions, and today the number of RFC authors is in the thousands, with involvement in the Internet standards-making process open to anyone who is interested enough.

“One thing that I love though is that these RFCs are just sitting out there,” says Darius. “It’s history that’s just there — anyone could look at them. I started looking at them because I just changed a number in a URL.

“I wouldn’t teach a foundation computer science class this way, but you can more or less learn how the Internet works from first principles by reading all the RFCs in order. It’s kind of amazing, but these things are just there.”

Darius plans to round out the project with some additional posts on the running themes of the RFCs in the project and the involvement of women in the early ARPANET.

You can visit the 365 RFCs project here, and can subscribe to it via its RSS feed. If you’re on a federated ActivityPub social network like Mastodon or Pleroma you can search for the user @365-rfcs@write.as and follow it there.

And of course, if you were wondering, there is an RFC for the 50th anniversary of the RFC — RFC 8700.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Wonderful writing it’s given a chance to understand

how protocol started through RFC in early Internet. Some RFCs evolved in many ways to supporting end user. Thanks a lot for taking back into early RFCs.