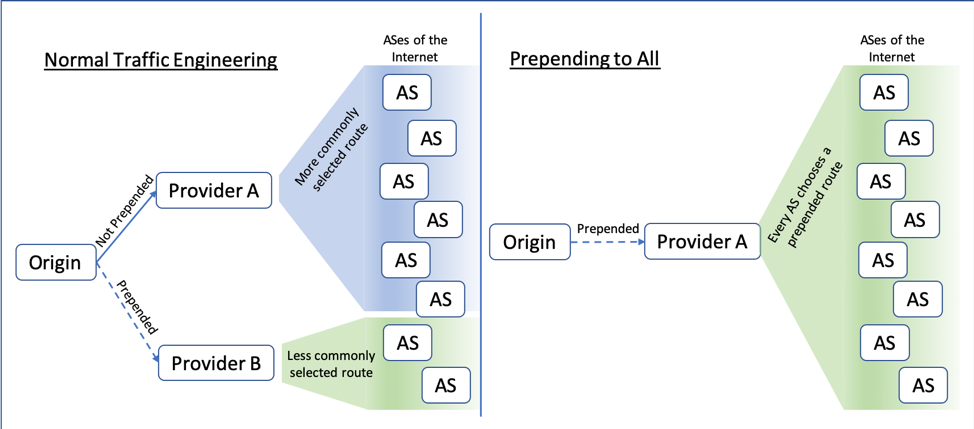

In the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), prepending is a technique used to deprioritize a route by artificially increasing the length of the AS-PATH attribute by repeating an autonomous system number (ASN). Route selection in BGP prefers the shorter AS path length, assuming all other criteria are equal. Therefore, a prepended route should be selected less often.

To employ this technique correctly, a network operator would normally deprioritize a route by prepending their ASN in the AS-PATH attribute in their announcements to a subset of multiple transit providers. Unfortunately, as I will report below, prepending is frequently employed in an excessive manner such that it renders routes vulnerable to disruption or misdirection — accidental or otherwise.

Prepending during a routing leak

In April 2010, China Telecom experienced a routing leak that got a lot of people’s attention. Despite the oft-repeated assertion, China did not hijack 15% of the world’s traffic for 18 minutes, but we’ll save a more detailed debunking of that myth for another time.

While analyzing the leak, we noticed something peculiar. When we ranked the approximately 50,000 prefixes involved in the leak based on how many ASes accepted the leaked routes, most of the impact was constrained to Chinese routes. However, two of the top five most-propagated leaked routes (listed in the table below) were US routes! Was there some grand conspiracy to intercept traffic destined for these routes? Actually, it was due to something much more troubling: gratuitous AS-PATH prepending by the victim.

| Prefix | Origin | Economy | Max Peer (%) | |

| 1 | 202.100.192.0/19 | 4134 | CN | 97.05 |

| 2 | 202.100.224.0/19 | 4134 | CN | 96.46 |

| 3 | 12.4.196.0/22 | 12163 | US | 87.61 |

| 4 | 12.5.48.0/21 | 12163 | US | 87.61 |

| 5 | 59.42.0.0/16 | 4134 | CN | 87.02 |

During the routing leak, nearly all of the ASes of the Internet preferred the Chinese leaked routes for 12.5.48.0/21 and 12.4.196.0/22 because, at the time, these two Chinese prefixes were being announced to the entire Internet along the following excessively prepended AS-PATH:

… 3257 7795 12163 12163 12163 12163 12163 12163

With this odd configuration, virtually any illegitimate route, whether a deliberate hijack or an inadvertent leak, would be preferred over the legitimate route. Think about that for a minute. In this case, the victim is all but ensuring their victimhood.

Prepending to everyone!

There was only a single upstream seen in the prepending example from above, so the prepending was achieving nothing while incurring the risk of hijacked traffic during a routing leak or hijack.

You’d think such mistakes would be relatively rare, especially now, almost 10 years later. As it turns out, there is quite a lot of prepending-to-all going on right now. And during leaks, it doesn’t go well for those who make this mistake.

While one can debate the merits of prepending to a subset of multiple transit providers, it is difficult to see the utility in prepending to every provider. In this configuration, the prepending is no longer shaping route propagation. It is simply incentivizing ASes to choose another origin if one were to suddenly appear whether by mistake or otherwise.

Figure 1 — Normal traffic engineering vs. prepending to all.

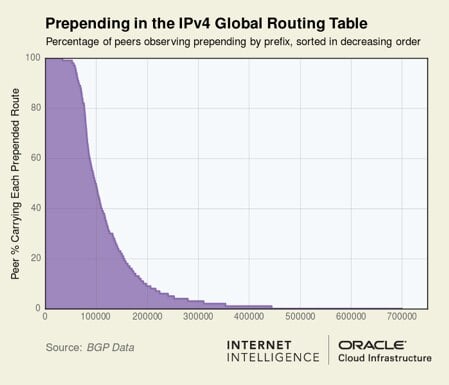

So how many prefixes in the global routing table are prepended-to-all? The number might surprise you: out of approximately 750,000 routes in the IPv4 global routing table, nearly 60,000 BGP routes are prepended to 95% or more of our hundreds of BGP sources. So about 8% of the global routing table or one out of every twelve BGP routes is configured with prepends to virtually the entire Internet! The 60,000 routes include entities of every stripe: governments, financial institutions, even important parts of Internet infrastructure.

Figure 2 shows the degree to which each prefix in the IPv4 and IPv6 global routing tables is prepended to other ASes of the Internet. At least 100,000 IPv4 prefixes (13.3%) and over 6,000 IPv6 prefixes (8.6%) are seen as prepending to over half of our peers.

Figure 2 — Prepending in the IPv4 and IPv6 global routing tables.

We argue that prepending-to-all is a self-inflicted and needless risk that serves little purpose. Those excessively prepending their routes should consider this risk and adjust their routing configuration.

The risk

The risk of this behaviour can perhaps be best illustrated with a real-world example. Consider the Ukrainian prefix (95.47.142.0/23) which is normally announced with an inordinate amount of prepending. A recent analysis revealed that 95.47.142.0/23 is announced to the world along the following AS path:

… 3255 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158 197158

In this example, the origin AS197158 appears 23 consecutive times before being passed on to a single upstream (AS3255), which passes it on to the global Internet, prepended-to-all.

An attacker wanting to intercept or manipulate traffic to this prefix might enlist a data centre of questionable morals who would allow announcements of the same prefix with a fabricated AS path such as:

… 999999 3255 197158

Here the fictional AS999999 represents the shady data centre. This malicious route would be pretty popular due to the shortened AS path length and might go unnoticed by the true origin, even if route-monitoring had been implemented. Standard BGP route monitoring checks a route’s origin and upstream and both would be intact in this scenario. The length of the prepending gives the attacker room to craft an AS path that would appear plausible to the casual observer, comply with origin validation mechanisms, and not be detected by off-the-shelf route monitoring.

Over the years, we’ve reported on the Dyn/Oracle Blog numerous instances of malicious routes with AS paths crafted to look plausible (see The Vast World of Fraudulent Routing: Case 5, Ukraine Emerges as Bogus Routing Source, BackConnect’s Suspicious BGP Hijacks ), so we know this happens.

Of course, an inadvertent origin leak could also disrupt traffic to this route. Accidents happen, so why deliberately put your routes at risk? We have asked a number of network operators if they could explain the purpose of their excessive prepending and we have yet to receive a rationale for this routing configuration.

Prepending behaviour

So what happens when a non-prepended route competes against an excessively prepended route? Let’s consider a real-world example from last month.

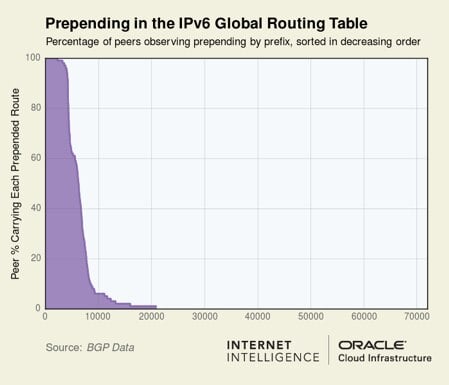

The Polish route 91.149.240.0/22 is normally announced with the origin prepended three times (41952, 41952, 41952) to three providers and prepended twice to a fourth. Beginning at 15:28:14 UTC on 6 June, a new origin that was not prepended appeared in the routing table for this route. As is illustrated in the graphic below, AS60781 quickly became the most popular version of this route for the next week until it disappeared (see majority red region in Figure 3).

Figure 3 — The non-prepended route AS60781 was more popular than the prepended route AS41952 for 91.149.240.0/22.

When both AS41952 and AS60781 were in contention for being considered the origin of this prefix, the non-prepended route was dominating — as we would expect.

In some cases, the impact of prepending isn’t as straightforward.

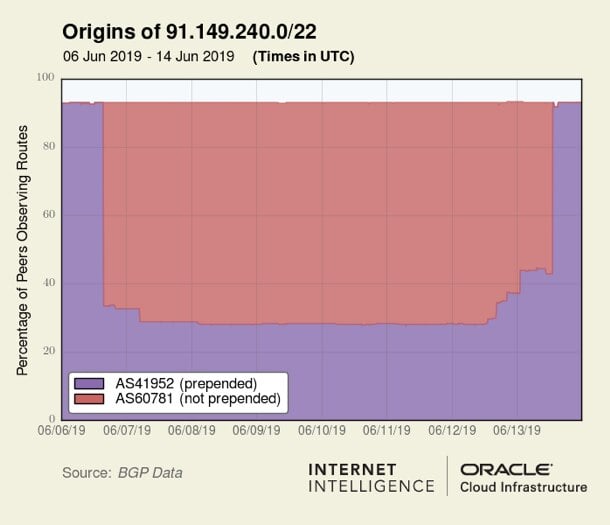

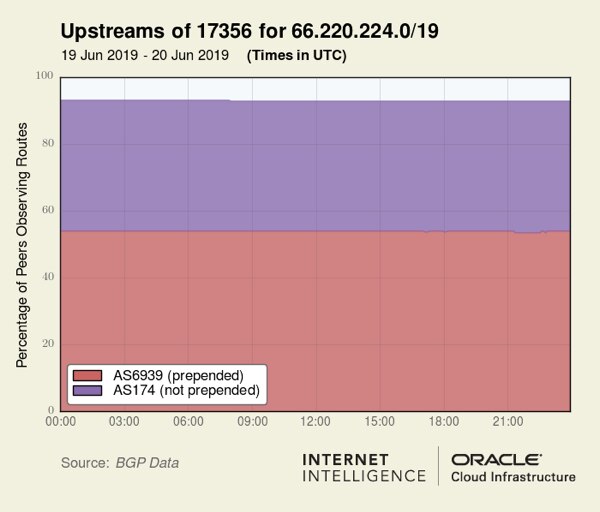

Let’s take 66.220.224.0/19 as an example. This prefix is prepended but isn’t one of the 60,000 prepended-to-all routes mentioned earlier because its prepending is only visible to a little more than half of our BGP sources. In any event, this prefix is announced to the Internet in two ways: it’s prepended to AS6939 and not prepended to AS174:

… 174 17356

… 6939 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356 17356

From these two route options, one might reasonably infer that it is 17356’s intention to deprioritize routes to AS6939 by prepending itself 10 times on routes to that upstream. It may seem to follow that the non-prepended path to AS174 would be the most popular. However, the opposite is true. Figure 4 illustrates the percentage of our BGP sources, that is, our peers, that see either AS6939 or AS174 as an upstream of AS17356 for 66.220.224.0/19.

Figure 4 —Percentage of peers observing routes from prepended AS6939 and non-prepended AS174.

Despite extensive prepending, AS6939 is the more popular choice. In this case, prepending is going up against the local preferences of a legion of ASes: AS6939 has an extensive peering base of thousands of ASes. These ASes opt to send traffic for free through their AS6939 peering links instead of having to pay to send traffic through a transit provider (and via AS174) regardless of the AS path length. AS17356 could prepend their routes to AS6939 100 times (please don’t!) and AS6939 would still be the more popular provider.

Keep in mind that the average AS diameter of the Internet is only around 4 hops, so prepending more than a couple of times buys you nothing.

How did this come to be?

The routing experts we consulted offered a few theories as to how we arrived at this state.

Theory 1: Poor housekeeping

Imagine an AS is prepending to one of its two transit providers in order to deprioritize the prepended one. Then imagine the relationship with the non-prepended transit provider goes away and the AS is left with only the prepended provider. The AS forgets to remove the prepending and is then announcing only prepended routes to the entire world, unaware of the risk incurred by these artificially elongated AS paths.

Theory 2: Return path influence

Another theory is that this is a deliberate, yet misguided, tactic to influence the return path of traffic from peers. The large routing leak of November 2017 that disrupted communications for many users in North America caused such an impact due to the leak of thousands of more-specific routes that were being employed to ensure return traffic travelled directly over a peering link.

Might some ASes be prepending to the entire Internet to make non-prepended direct links with peers more likely to be chosen? Perhaps. Typically, ASes already prioritize sending traffic to settlement-free peers to save on transit costs, so prepending the transit paths would seem to be unnecessary and unwise considering the risks described above.

Theory 3: Mistakes abound

There are simply a lot of errors in BGP routing. Consider the prepended AS-PATH of 181.191.170.0/24 below:

… 52981 267429 267429 267492 267492 267429 267429 267492 267492 267429 267429 267492 267492 267429

In case your eyes didn’t catch it, the prepending here involves a mix of two distinct ASNs (267429 and 267492) with the last two digits transposed. This tapestry of typos (typostry?) is announced to the global Internet for five of AS267429’s six originated prefixes. It is likely many ASes are simply unaware they are excessively prepending their prefixes.

Conclusion

When I shared these results with BGP expert Job Snijders of NTT Ltd, he responded:

“It’s startling, but AS-PATH prepending has transformed from a traffic-engineering utility function into a device that increases risk. Considered from a routing security perspective, in almost all cases AS-PATH prepending should be considered harmful.”

Additionally, Brazilian researcher Pedro Marcos recently asked on the APNIC blog, ‘Can AS-PATH prepending compromise the security of Internet routing?’

Prepending has been a core traffic engineering technique as long as BGP has been directing traffic around the Internet. If one’s transit providers don’t offer BGP communities to enable traffic engineering, prepending may be seen as the only alternative to shape route propagation.

Long AS paths (whether due to prepending or otherwise) incur the risk of disruption (or possibly interception) in the event another AS originates the same prefix with a shorter AS path. Network operators should review whether they are presently prepending and make sure it is absolutely necessary. With 8% of the IPv4 and 5.6% of the IPv6 global routing tables presently prepended to essentially everyone, we can confidently assert that this traffic engineering technique is significantly overused today.

Adapted from original post which appeared on the Oracle Blog.

Doug Madory is a Director of Internet Analysis of Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Team where he works on Internet infrastructure analysis projects.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Thanks for highlighting this. While reviewing the routing table I found another gem.

64098 174 9498 55644 135253 135253 135253 135253 135253 135253 135253 135253 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597 137597

I was searching for the meaning of BGP AS prepending for almost 30 mins and I didn’t get it.

Once I read the first 3 lines of the article now I can understand it normally.

Thank you for the clarification.

“Remember, the average AS path length on the Internet is about 4 hops, so adding more than a couple of prepends won’t be effective.”

In your opinion, how many prepends would be sufficient to redirect traffic from ISP1 to ISP2?