Manatua is a new submarine cable that will link Samoa with Tahiti, picking up Niue, Aitutaki, Rarotonga, and Bora Bora along the way. Its Rarotonga and Aitutaki landings will be the first fibre optic connectivity for the Cook Islands, who today access the Internet through an O3b medium-earth-orbit satellite link to Honolulu.

Manatua will bring traffic from the Cook Islands to the landings of several existing submarine cables, with onwards connectivity to Australia, New Zealand and the United States.

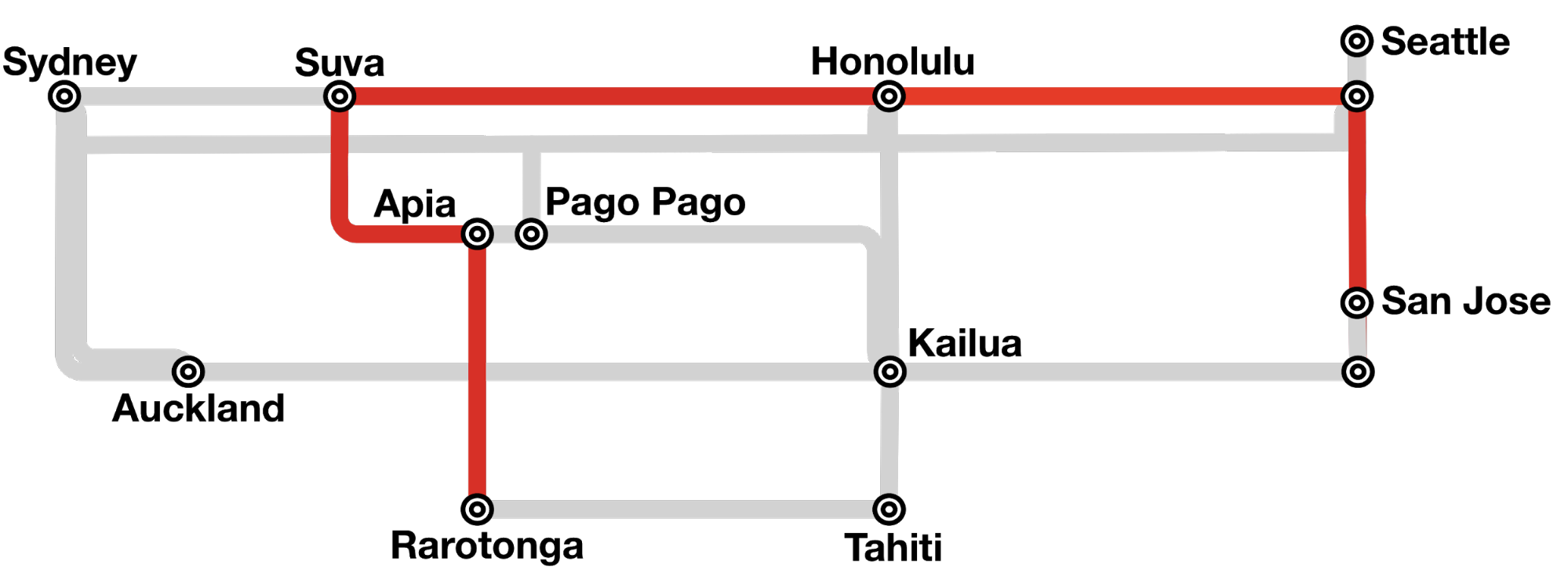

The diagram below is a simplified view of that connectivity set up like a subway map.

Figure 1 — Manatua and its interconnections in the Pacific.

Once the Cook Islands are connected to their neighbours via Manatua, what will be the best way for them to connect to the global Internet? We’ll explore that topic today.

About the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands is one of the most remote places on earth. Around 18,000 people live in the Cook Islands, with 75% of the population concentrated on the island of Rarotonga. Another 60,000 Cook Islanders live in New Zealand and 16,000 in Australia.

Tourism accounts for 60% of the GDP of the Cook Islands, well ahead of any other industry or exports. More than 160,000 tourists visited in 2017 with nearly three quarters coming from Australia or New Zealand. Aside from tourism, the Cook Islands’ economy is supported by primary industries like fishing, with most exports going to Japan and Thailand, and to a lesser degree, offshore banking and asset protection used mainly by Americans.

Project background

The Manatua cable will be a point-to-point connection between Apia and Tahiti, with branching units to Niue, Aitutaki, Rarotonga and Bora Bora. It will solve problems for all connected parties. French Polynesia has wanted to improve the resilience of their single cable since it was commissioned in 2010. Samoa has a goal of becoming the Information Technology hub for the South Pacific by 2020. And the Cook Islands has been thinking of moving away from satellite since 2013; their Manatua project having been underway since 2016.

In October 2018, all of the financial issues between the parties were agreed upon, and TE Subcom was contracted to build the cable on 20 November. Cook Island obligations are being funded with a USD 15 million grant from the New Zealand government, and a USD 15 million loan from Asia Development Bank (ADB). The Cook Islands’ government will have a five-year grace period, a 20-year repayment term on the loan, and a floating interest rate based on LIBOR.

What good is a submarine cable?

Elected officials and government representatives in the Pacific often talk about submarine fibre being a faster connection to the global Internet, but in practice they mean a faster connection to the USA. Samoa Submarine Cable Company’s reference offering, for example, is a point-to-point service that connects Samoan users to the Internet in San Jose, California.

Connecting to the USA however isn’t always what users of the Internet want. A representative of the local media said the local carrier finds most of its traffic destined for a few sites:

| YouTube | Netflix | |||

| Putlocker | Snapchat | Spotify | Fortnite |

While all these services are available in California, every single one is also available in Sydney, and some in Suva and Auckland. And users of these services from Australia and New Zealand are likely to have their personal data stored on servers in their home markets, not in the USA.

After connections to popular cloud services, what do people use the Internet for? Voice and video calling. This means Skype, Facetime, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and others. If most of those calls are to Australia, New Zealand, or export markets like Japan or Thailand, is sending all Internet traffic to the USA a good idea at all?

All of these services — social media and calling alike — depend on fast connections between users and servers to work well. In most cases, a return-trip delay (or latency) of more than 240 ms will be perceived as slow.

The best ways to connect

Getting the best performance for Internet users should be a goal of operators using the new cable. Here we’ll look at a few different ways the Cook Islands could connect to the Internet and how it would impact performance on their users.

| Samoa Submarine Cable: Capacity Lease | |

| Samoa’s default Internet offerings pick up traffic in Apia and join it to the Southern Cross Cable Network (SCCN) at Suva, before connecting it to the Internet in California. Traffic does not connect to the Internet at Suva or Honolulu, these are both accessed via the US West Coast. Because Fiji is on the northern part of the SCCN, traffic to the US travels through Oregon to get to California. | |

| Latency for Facebook and Google | 153 ms |

| Latency for most cloud applications | 153 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to Australia | 301 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to New Zealand | 278 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to California | 153 ms |

Figure 2 — Samoa Submarine Cable: Capacity lease.

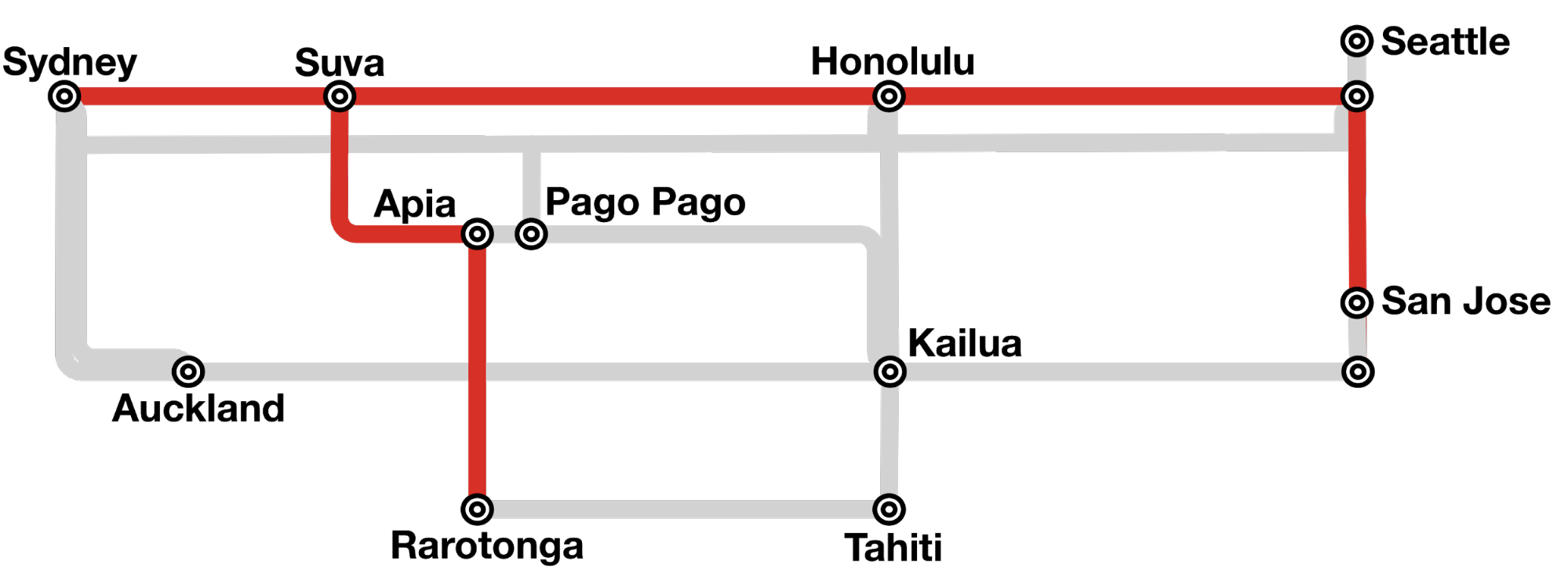

| Submarine Cable: Capacity IRU + Fintel | |

| Users of the Samoa cable can also purchase the right to use a 10 Gbps connection from Apia to Suva. In Suva, the wholesale carrier Fintel sells Internet access, with direct connectivity to Fiji, Oregon and Sydney. Facebook and Google both have caches present in Suva. Sourcing capacity in Fiji can be expensive as Fiji’s commerce commission has set costly landing fees. | |

| Latency for Facebook and Google | 32 ms |

| Latency for most cloud applications | 68 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to Australia | 68 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to New Zealand | 91 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to California | 153 ms |

Figure 3 — Samoa Submarine Cable: IRU + Fintel.

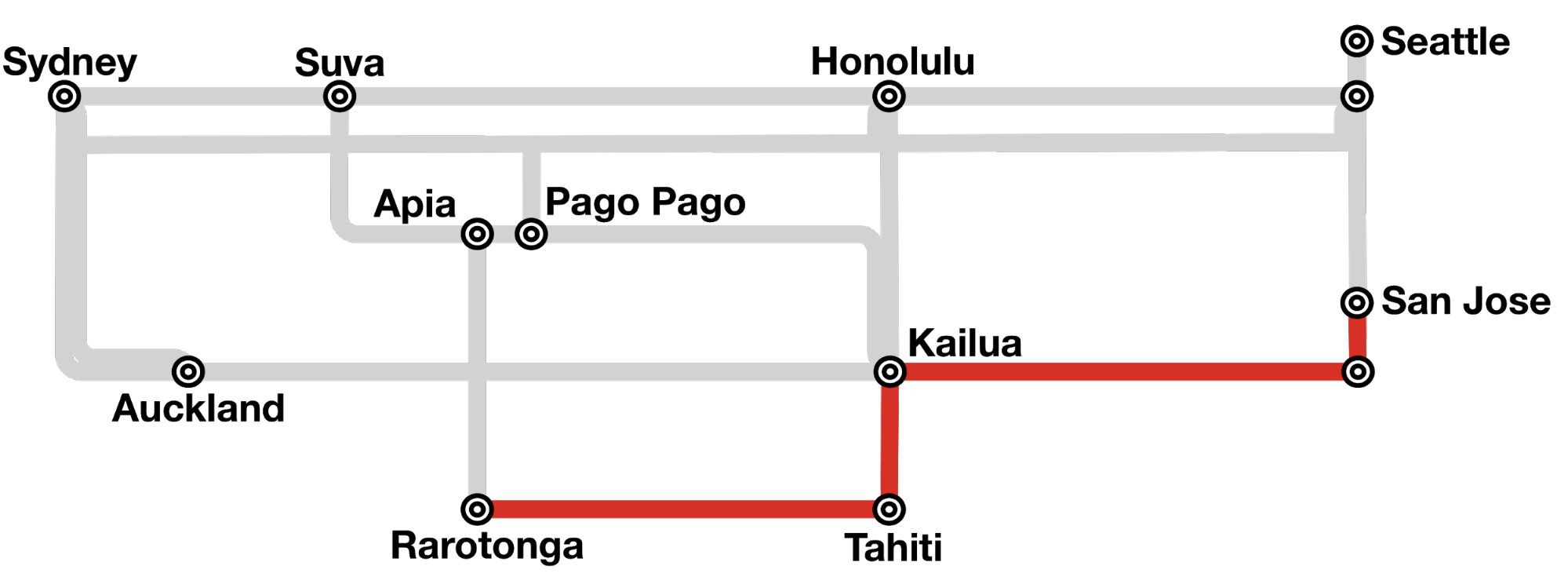

| Office des Postes et Télécommunication (OPT): Honotua | |

| OPT operates a cable from Tahiti to Kailua, Hawaii, with onward capacity to Southern California. Facebook and Google both have caches present in Tahiti. OPT can provide the Cook Islands with the fastest possible path to California. | |

| Latency for Facebook and Google | 13 ms |

| Latency for most cloud applications | 105 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to Australia | 251 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to New Zealand | 230 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to California | 105 ms |

Figure 4 — Office des Postes et Télécommunication (OPT): Honotua.

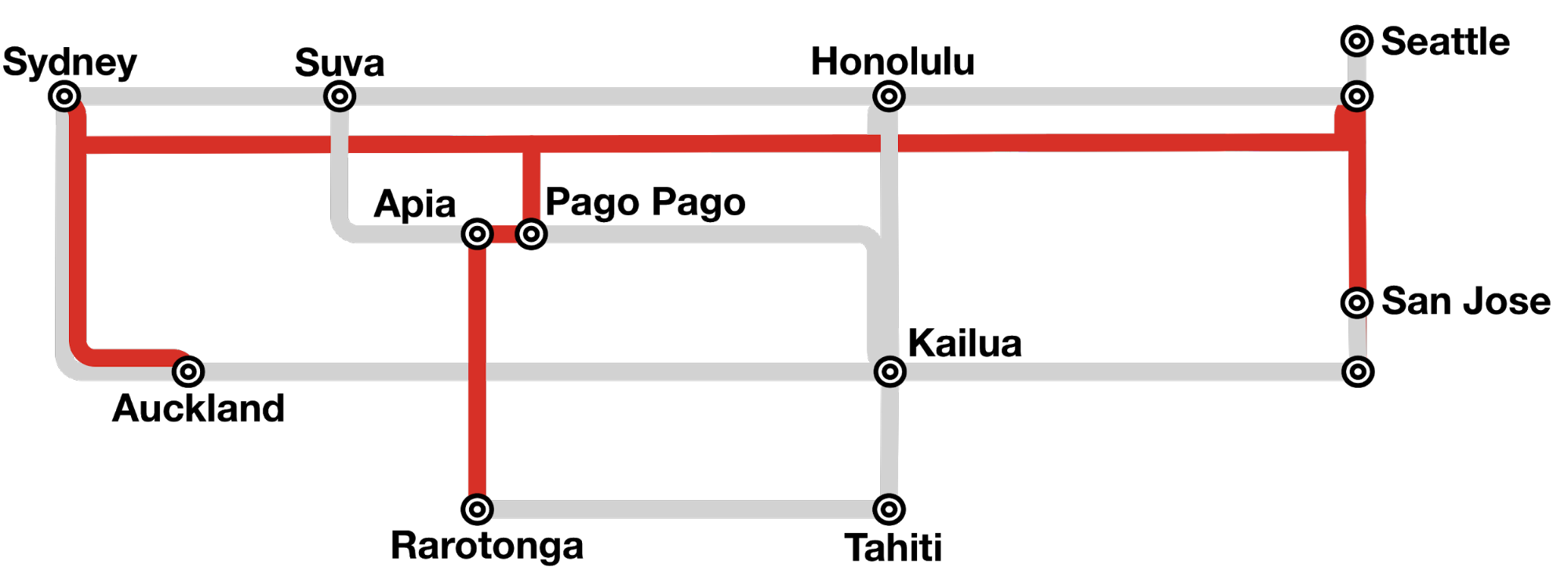

| SAS + Hawaiki | |

| The SAS cable is an small segment of fibre optic between Apia, Samoa and Pago Pago, American Samoa. Hawaiki is a new cable between Sydney and Oregon, with branching units connecting Auckland and Honolulu. Connecting via SAS and Hawaiki would provide the best performance from the Cook Islands to New Zealand of any possible solution. | |

| Latency for Facebook and Google | 60 ms |

| Latency for most cloud applications | 68 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to Australia | 68 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to New Zealand | 60 ms |

| Latency for voice and video to California | 125 ms |

Figure 5 — SAS + Hawaiki.

In summary

The table below sums up options, banding latencies as sub-100 ms (green), 100-200 ms (yellow), and over 200 ms (blue).

| SSCC capacity | IRU + Fintel | Honotua | SAS + Hawaiki | |

| Facebook and Google | 153 ms | 32 ms | 13 ms | 60 ms |

| Cloud applications | 153 ms | 68 ms | 105 ms | 68 ms |

| Australia voice and video | 301 ms | 68 ms | 251 ms | 68 ms |

| New Zealand voice and video | 278 ms | 91 ms | 230 ms | 60 ms |

| California voice and video | 153 ms | 153 ms | 105 ms | 125 ms |

In an ideal world, the Manatua cable would connect the Pacific Islands to each other, and Internet capacity would be available for purchase inexpensively in hubs like Samoa and Fiji. Traffic from the Cook Islands would take any available path, and the lowest latency connection to all endpoints would always be used. The Cook Islands would send its California-bound traffic via Tahiti, its Fiji-bound traffic via Samoa, and its Australia and New Zealand traffic on Hawaiki.

That said, Australia and New Zealand traffic should be considered above all else, because from a cultural and economic perspective, the Cook Islands looks west, not east to the USA.

Commercial realities mean it’s unlikely the Cook Islands will be able to get economic connectivity from its neighbours, and a single-path solution will be taken to meet the economy’s needs, perhaps backed up using existing satellite arrangements. In that case, the obvious winner from an end-user perspective will be a short hop from Apia to Pago Pago, and service on the Hawaiki Cable.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Nice summary! It’s complex… One point that warrants consideration beyond the destination for the traffic is what sort of traffic it actually is. The first question to ask in this context is whether the traffic is TCP (where a long RTT slows down the opening of a TCP sender’s congestion window and, in combination with shared bandwidth bottlenecks, can lead to TCP queue oscillation). Streaming services do not use single download TCP sessions for this reason – they have an array of alternatives, from UDP-based download which gloss over data loss or use forward error correction schemes to deal with lost traffic to splitting the media up into a series of comparatively small downloads. The likes of Youtube, Netflix and Spotify are not “real-time” in the sense of Skype, so RTT doesn’t matter here so much.

If it’s TCP, the second question to ask is how long/large the typical TCP flows from a particular origin are. Most major providers on the list above make use of content delivery networks and are indeed having POPs in all major places such as Sydney and the US West Coast. However, much of their content is small fry volume-wise: text and resolution-reduced photos on Facebook and Instagram – an entire HTTP response fits within the packets of the initial congestion window, and again RTT doesn’t play much of a role here as those packets get transmitted immediately and the browser client will render once the data has arrived – even if the originating server has yet to see the ACKs for it.

That said, RTT does come into the game once web pages resolve their content recursively: the top HTML page loads style files, scripts, images, etc., which in turn may cause further HTTP requests, each of which takes at least one RTT to complete.

Where RTT definitely matters in the TCP domain is when large TCP transfers are involved: software downloads and updates, large e-mail attachments or uploads (yes those tourists in Raro uploading their video clips of the day’s snorkeling fall into that category). Large downloads often originate in the US, as many of the main software vendors and countless application developers are located there, and not all of them use content delivery networks.

I note in this context that many users in islands on satellite links with volume charging never turn automatic updates on – probably one reason why the Cook Islands site list above does not feature Microsoft on a regular basis. So if a connectivity improvement is on the cards, it’s also worth considering what might change in what people access and where these resources are located.

Then there’s also the possibility that the Cook Islands’ legal environment might prove attractive for services that are difficult to run elsewhere, and that a cable-connected Rarotonga might become a net data exporter – perhaps even for all the wrong reasons, too…

Well written and explained very well in detail. I hope this helps the Cooks to select the best possible path for BGP peering.

Thank you for this comprehensive report Jon. It really helps us understand some of the factors affecting our route selection, price being the other consideration. Really appreciate all the effort you have made for us.