This post was co-authored by Raffaele Sommese, Anna Sperotto, Antonio Prado, Jeroen van der Ham, and Antonia Affinito.

The new Italian anti-piracy platform, Piracy Shield, requires Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block reported IPs and fully-qualified domain names (FQDNs) within just 30 minutes of identification. Supporters hail it as a highly effective system, often pointing to the large number of streaming resources blocked.

Critics, however, highlight the darker side: Repeated cases of overblocking, including the unintended disruption of widely used services such as Google Drive. What remains missing is a clear view of the platform’s broader impact.

Our study shines a light on what has so far been hidden, revealing:

- Extensive collateral damage affecting hundreds of legitimate services, often the byproduct of blunt IP-level blocking on shared infrastructure.

- Resilient evasion strategies, from rapid domain migrations and unfiltered IPv6 to fast-changing IPv4 leases.

- Systemic risks when blocks spill over onto critical services such as Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), anycast networks for Distributed-Denial-of-Service (DDoS) protection, and other vital dependencies.

These findings call for a rethink. We argue that Piracy Shield must move toward a cautious, FQDN-first approach, reinforced with time-limited blocking, transparent reporting, and streamlined procedures for notification and unblocking. These measures can curb piracy without breaking the Internet in the process.

Why this is crucial for operators

Blocking live events is a race against the clock. Network operators are often asked to act within minutes, usually with little context and under significant operational pressure. As blocking expands to IP space, the chances of targeting shared resources and over-blocking — and the attendant fallout — only increase. Having visibility into the real footprint of these measures helps ISPs prepare, put safeguards in place, and work with regulators on solutions that reflect operational realities.

Piracy Shield in brief

Privacy Shield was introduced as a legal requirement in 2023 and further developed throughout 2024 and 2025. Piracy Shield facilitates the swift blocking of IP addresses and FQDNs to protect live content, initially focused on football broadcasts and later extended to include a wider range of audiovisual material.

The list of blocked resources remains inaccessible to the public, although tools are available for checking individual resources. However, these do not support bulk exports.

Several high-profile incidents brought attention to instances of excessive blocking affecting shared infrastructures such as CDN subdomains and IPs belonging to major providers. These cases have fueled ongoing discussions surrounding proportionality, transparency, and adherence to European Union (EU) compliance standards.

Shedding light on the blocklist

For months, the blacklist behind Italy’s Piracy Shield has remained in the shadows. AGCOM, the regulator in charge, has been repeatedly pressed by citizens and operators to release the list through freedom of information-style requests. Every single time, the answer was the same: Denied, with little or no explanation given.

The only official options were two lookup tools: AGCOM’s own portal and a page run by Infotech, an Italian ISP. They let you check a single IP or domain at a time, but nothing more. No broader visibility, no transparency. Several operators referred to a GitHub repository that had been quietly publishing and regularly updating the full list of blocked IPs and domains since October 2024. Debate quickly followed: Was this leak legitimate, or just random data?

We decided to find out. By manually cross-checking entries from the leak against the official tools, we confirmed its accuracy. What emerged was the first validated dataset of Piracy Shield’s blocking activity, complete with dates, status changes, and even evidence of when certain resources were quietly unblocked. At this point, the black box wasn’t so black anymore.

Hosting within the EU dominates the piracy infrastructure

| Autonomous System Number (ASN) | Name | Number of IPs (% of total) | Number of /24s | Number of Unblocked IPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 142019 | GZ Remittance | 1,035 (9.5%) | 15 | 1 |

| 62390 | NexonHost | 834 (7.6%) | 31 | 6 |

| 16276 | OVH | 719 (6.6%) | 494 | 41 |

| 214785 | 369 IntoNet | 610 (5.6%) | 6 | 1 |

| 25198 | ZetServers | 452 (4.1%) | 35 | 9 |

| 64286 | LogicWeb | 408 (3.7%) | 7 | 0 |

| 141718 | IPv4 Superhub | 406 (3.7%) | 19 | 1 |

| 58349 | INNETRA PC | 295 (2.7%) | 8 | 2 |

| 30860 | Virtual Systems | 261 (2.4%) | 35 | 2 |

| 12876 | SCALEWAY | 260 (2.4%) | 169 | 4 |

| 43139 | Maximum-Net | 258 (2.4%) | 3 | 0 |

| 215224 | NovoServe | 226 (2.1%) | 26 | 2 |

| 24940 | Hetzner | 191 (1.8%) | 162 | 3 |

| 47647 | Hostpalace | 171 (1.6%) | 11 | 4 |

| 64006 | Net Solutions | 161 (1.5%) | 14 | 3 |

| Others | — | 4,631 (42.4%) | 1,099 | 73 |

| Total | — | 10,918 (100%) | 2,134 | 152 |

| Economy | Number of IPs (% of total) |

|---|---|

| NL | 4,135 (37.9%) |

| DE | 985 (9.0%) |

| RO | 898 (8.2%) |

| US | 843 (7.7%) |

| UA | 676 (6.2%) |

| FR | 636 (5.8%) |

| SE | 634 (5.8%) |

| GB | 396 (3.6%) |

| IT | 275 (2.5%) |

| HK | 265 (2.4%) |

| Others | 1,175 (10.8%) |

| Total | 10,918 (100%) |

Once we had reconstructed the blocklist, the next question was obvious: Where exactly are pirates hosting their infrastructure? We started with the blocked IPs: Out of just over 10,000 blocked addresses, one company alone accounted for nearly a thousand. The top 10 providers together hosted more than half of all blocked IPs, showing a striking concentration of pirate activity around a small set of providers.

But the real surprise was geographical. Nearly 77% of the blocked IPs were located inside the European Union, a jurisdiction where Italian copyright holders should, in theory, have more leverage to pursue illegal streaming operators through established legal and law enforcement channels, rather than relying on blunt blocking measures.

The picture became even more interesting when we looked at individual providers. Some, like OVH, showed a high number of unblocked addresses, a pattern suggesting that shared hosting environments, where legitimate services sit side by side with pirate streams, were frequently caught in the crossfire, leading AGCOM to later reverse some of its own blocks.

In search of collateral damage

An IP address is rarely tied to a single resource. The same machine can run a website, a mail server, and a DNS service, or host dozens of unrelated websites through virtual hosting. On top of that, providers often recycle IPs, assigning them to new customers once they are freed.

In the context of Piracy Shield, this creates the perfect storm. Since blocks are applied almost indefinitely, the natural churn of Internet hosting means that one decision to block a pirate stream can later drag down completely unrelated, legitimate services.

To dig into this, we relied on two large-scale Internet measurements: The OpenINTEL DNS dataset and a full DNS measurement of FQDNs derived from certificate transparency logs. In those, we looked for signs of unintended damage — disruptions to web hosting, email delivery, and even the DNS itself.

IP-level blocking causes major collateral damage

| Blocked Resource | FQDN collateraly blocked | Confirmed non-streaming | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completely | Partially | Completely | Partially | |

| cname | 240 | 59 | 2 | 0 |

| cname ∩ ip | 82 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| ip | 6,027 | 188 | 373 | 14 |

| ip ∩ mx ip | 187 | 4 | 32 | 0 |

| ip ∩ mx ip ∩ mx ip | 28 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| ip ∩ ns ip | 3 | 32 | 1 | 0 |

| mx ip | 142 | 10 | 69 | 3 |

| mx ip ∩ mx name | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| mx name | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ns ip | 0 | 87 | 0 | 10 |

| ns name | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 6,712 | 402 | 483 | 27 |

Table 3 — Collateral damage by type and impact. ∩ = ‘common to both sets’.

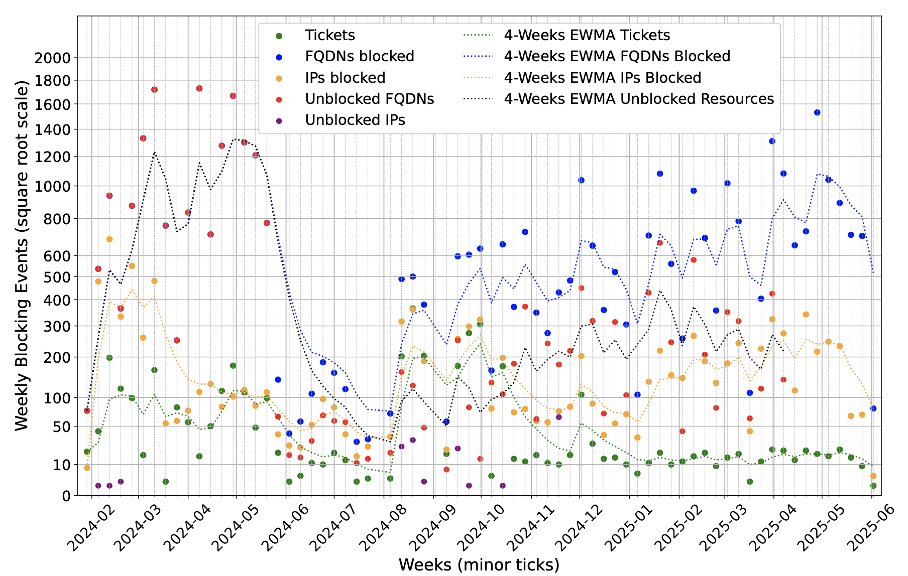

In June 2025, Piracy Shield was blocking 10,918 IPv4 addresses and 18,849 domains. From these, we measured collateral damage on 6,712 domains that were fully blocked and another 402 that were partially affected by those blocks.

We checked these domains one by one, looking for active websites and classifying their content. We found that more than 500 confirmed websites unrelated to streaming were blocked, and over time, the number of affected sites went into the thousands.

Most of the damage came from IP-level blocking. In shared hosting, or when providers reassigned an IP after abuse, a single blocked address could take down dozens of unrelated domains. In some cases, one IP block was enough to silence entire groups of legitimate services.

Blocking goes beyond web services. It can disrupt essential infrastructure. For example, authoritative DNS or mail exchange (MX) servers caught in the block list can lead to outages. Even partial name-server blocking introduces vulnerability, particularly in configurations relying on single authoritative servers.

Furthermore, blocks frequently affect anycasted DDoS-protection networks like StormWall, DDoS-Guard, and X4B. This is especially problematic during active DDoS mitigation efforts when sites are migrating to those IPs to counter attacks.

One case even revealed that a page related to Piracy Shield blocking, with a Google IP address, was being blocked. This underscores how enforcement tools can unintentionally lead to self-inflicted collateral damage.

Historical data shows prolonged exposure to collateral damage for affected domains, with median durations extending for months and average durations in the hundreds-of-days range. Many legitimate domain owners remain unaware they are impacted, often only discovering issues through user complaints or failed email transmissions originating from Italy.

Policy gaps encourage evasion strategies

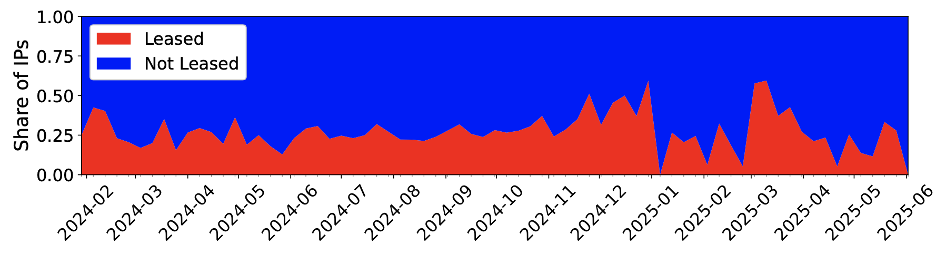

In this scenario, IPv6 remains practically untouched by enforcement efforts. Blocked FQDNs often adopt IPv6 post-blocking, creating direct bypass paths for users on public resolvers that do not implement the FQDN list. For IPv4, churn rates are high; many blocked FQDNs later resolve to new IPv4 addresses outside block lists.

Additionally, approximately 25% of blocked IPv4 addresses come from leased address spaces, and this is a conservative estimate. Variations in leasing practices across providers and the re-leasing of previously blocked addresses suggest the circulation of ‘polluted’ ranges back into use.

A call to action

Our results on the collateral damages of IP and FQDN blocking highlight a worrisome scenario, with hundreds of legitimate websites unknowingly affected by blocking, unknown operators experiencing service disruption, and illegal streamers continuing to evade enforcement by exploiting the abundance of address space online, leaving behind unusable and polluted address ranges.

Still, our findings represent a conservative lower-bound estimate. Our visibility into the global DNS is not exhaustive, and our damage assessment focused on HTTP(S) availability, likely missing cascading disruptions on other services like application programming interfaces (APIs), email, or databases that rely on direct IP connectivity.

The platform’s impact is multifaceted:

- Economically, it disrupts legitimate businesses, from Italian mechanics to international hosting providers who lose connectivity with their customers.

- Technically, it risks systemic failure by blocking shared infrastructure like CDNs and DDoS protectors while polluting the IP address space for future, unsuspecting users.

- Operationally, it imposes a growing, uncompensated burden on Italian ISPs forced to implement an expanding list of permanent blocks.

The evidence of widespread and difficult-to-predict collateral damage suggests that IP-level blocking is an indiscriminate tool with consequences that outweigh its benefits, and should not be used.

Instead, AGCOM and copyright holders should prioritize legal pathways to pursue the majority of illegal streamers, many of whom operate within the EU.

Finally, we argue that the authority should publish the list of blocked resources immediately after enforcement, enabling third parties to vet the action and ensuring a responsive task force can promptly address unintended disruptions.

We hope that this work sparks a thorough discussion among Italian operators, AGCOM, and national policymakers on reconsidering the Piracy Shield initiative. This reflection must account for the significant collateral damage to legitimate infrastructure and the potential threat to national security that the platform may pose. Ultimately, the challenge is not whether piracy should be fought, but how to do so without endangering the very principles and infrastructure that sustain the Internet as we know it.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the ITNOG and RIPE communities for their early insights and all contributors who assisted in validating our measurement methodologies and datasets. This summary highlights key points from a paper accepted at CNSM 2025.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.