HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) is a way to signal to a web client that valid HTTPS certificates must be used when connecting to a domain. There are two main benefits to HSTS.

First, it prevents a user from connecting over an unencrypted HTTP connection. Unencrypted HTTP leaks data to the network and is vulnerable to manipulation in man-in-the-middle attacks.

Second, it prevents a user from connecting if the server presents an untrusted TLS certificate. Users aren’t great at deciding if a warning message about an untrusted TLS certificate is a security concern or just a misconfiguration. They don’t have the knowledge or tools to decide, and they may inadvertently allow an attack to proceed by clicking through the warning.

A site that deploys HSTS has determined that it can encrypt all its web traffic with HTTPS and accurately manage its certificates.

HSTS preload is a mitigation against a very specific attack. A web browser needs to talk to a web server to see if it has HSTS headers. Once it does, it can cache those headers and it will be protected through the max-age expiration. However, that first load is vulnerable as the HSTS policy is not yet known (the bootstrap man-in-the-middle vulnerability). A malicious network operator could block HTTPS on port 443, for example, to try to trick browsers into thinking sites don’t support TLS. Web browsers ship with a large hardcoded list of domain names known to support HSTS — the HSTS preload list. As such, the first load of these websites can be protected.

Let’s look at some stats

Table 1 shows the HSTS status for the apex domain of the twenty most visited domains on the Internet:

| Domain | Chrome preload? | HSTS header value |

|---|---|---|

| 1. google.com | No | |

| 2. youtube.com | Yes | max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload |

| 3. facebook.com | Yes | max-age=15552000; preload |

| 4. twitter.com | Yes | max-age=631138519 |

| 5. instagram.com | Yes | max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload |

| 6. baidu.com | No | |

| 7. wikipedia.com | Yes | max-age=106384710; includeSubDomains; preload |

| 8. yandex.ru | No | |

| 9. yahoo.com | No | max-age=31536000 |

| 10. xvideos.com | No | |

| 11. whatsapp.com | Yes | max-age=31536000; preload; includeSubDomains |

| 12. pornhub.com | Yes | max-age=63072000; includeSubDomains; preload |

| 13. xnxx.com | No | |

| 14. amazon.com | No | |

| 15. tiktok.com | No | |

| 16. live.com | No | |

| 17. openai.com | No | max-age=10886400; includeSubDomains; preload |

| 18. reddit.com | Yes | max-age=31536000; includeSubdomains; preload |

| 19. docomo.ne.jp | No | |

| 20. linkedin.com | No |

I want to call out a couple of things. Only eight of the top twenty domains are on the Chrome HSTS preload list. Half aren’t using HSTS at their apex domain at all. Yahoo and OpenAI are using the HSTS headers, but they aren’t on the preload list.

What does this mean?

It depends on your browser settings. You should, right now, make sure you’ve enabled HTTPS-only mode. Unfortunately, this isn’t the default setting, so many users will still connect over HTTP in some situations.

Without this setting, clicking on a URL like http://google.com (insecure URL) will cause your browser to connect over unencrypted HTTP. Google responds by sending an HTTP redirect to the HTTPS site, but that redirect can be tampered with as it is served unencrypted. It could redirect to a malware or phishing site if you’re on an untrusted network.

yahoo.com is also vulnerable to these issues, but only the first time you connect. An HSTS-aware browser (98.5% currently) will cache the HSTS setting, preventing the use of HTTP or bogus TLS certificates until it expires (per the max-age directive). This is a significantly stronger position, as subsequent visits are forced to use HTTPS and require the TLS certificate to pass all validation checks.

The sites that support preload, like youtube.com, will always use HTTPS. Your browser knows before you ever connect that the site requires HTTPS, so it will never try HTTP.

Why doesn’t google.com support HSTS?

We’ve got to start with google.com. They’re at the top of the list in terms of traffic and Google manages the HSTS preload list. Google and its customers are frequent targets of state-sponsored hackers. Shouldn’t they be using HSTS?

They do use HSTS, but not at the apex domain:

| Subdomain | Chrome preload? | HSTS header value |

|---|---|---|

| www.google.com | No | |

| cloud.google.com | Yes | max-age=63072000; includeSubdomains; preload |

| drive.google.com | Yes | max-age=31536000 |

| docs.google.com | Yes | max-age=31536000 |

| maps.google.com | No | |

| pay.google.com | No | max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains |

| bard.google.com | No | |

| support.google.com | No | max-age=31536000; includeSubdomains |

| mail.google.com | Yes | max-age=10886400; includeSubDomains |

Google has lots of projects hosted as subdomains under google.com and they can’t enable domain-wide security settings until all subdomains can support them. HSTS headers are missing from several subdomains like, www and maps. Even very new projects, like the AI tool Bard, are being launched without HSTS support.

google.com demonstrates another interesting thing about the preload list. Some of the Google subdomains, like cloud, docs, and mail, are on the preload list even though the preload list doesn’t currently support adding subdomains. These must have been added before that rule took effect. The preload list is ever-growing, so there are space concerns and they’ve got to be careful about adding too many entries. The current list has 120,699 entries and a file size of 18MB. A per-subdomain list would be far too massive.

Google publishes a transparency report that shows how much of its traffic is encrypted using HTTPS. They’ve been stuck at ~95% for the last five years, so it looks like they’re still a long way from being HTTPS-only.

Let’s talk about porn

Private browsing windows (such as incognito in Chrome) don’t save the HSTS setting after the window is closed. This protects privacy, but has a security impact since every time is like the first time — there’s no cached HSTS setting to protect you. If most users are opening a site in a private window and closing it with every visit, HSTS headers are mostly useless.

xvideos.com and xnxx.com don’t support HSTS, although pornhub.com both supports HSTS and is on the preload list. Being on the preload list is probably more important here, as the HSTS headers have reduced effect.

What about Amazon?

amazon.com doesn’t set HSTS headers on the apex, but many of the subdomains use it. Let’s take a look.

| Subdomain | Chrome preload? | HSTS header value |

|---|---|---|

| www.amazon.com | Yes | max-age=47474747; includeSubDomains; preload |

| us.amazon.com | No | max-age=47474747; includeSubDomains; preload |

| sellercentral.amazon.com | No | max-age=47474747; |

| pay.amazon.com | No | max-age=63072000; includeSubDomains |

| aws.amazon.com | No | max-age=63072000 |

| console.aws.amazon.com | No | max-age=47304000; includeSubDomains |

I can’t find any subdomains of amazon.com without HSTS headers (can you?). Amazon looks much closer to enabling HSTS for their apex domain and adding it to the preload list than Google.

Are there any web clients that support HSTS but don’t support preload lists?

I found one.

A preload list is bulky and requires regular maintenance, so it’s difficult to ship it alongside most web clients. It sort of feels like something the operating system could provide, similar to the Certificate Authority trust roots, but no operating systems do this today.

I found that curl has optionally supported HSTS since 2021 and wget has supported HSTS since 2015 (currently enabled by default). wget supports preload lists and a third-party tool can import Chromium’s preload list. curl doesn’t support preload lists.

Excluding traditional web browsers, client-side support for HSTS is rare. The only HTTP client library I found supporting HSTS was libcurl. None of the other popular HTTP clients have HSTS support, including Python’s Requests, C++’s Boost, Java’s HttpClient, and others. Not even the venerable OpenSSL supports HSTS.

Software developers and other technical users just need to be careful it seems. Make sure you’re using https:// as most tools will happily use http://.

Are there preload lists other than Google’s?

Yes.

To get added to the Chromium preload list, a domain needs to configure HSTS headers, including a non-standard preload directive, and then manually request addition. Mozilla copies the Chromium list but validates each domain by checking that the HSTS headers are still present. Domains that are currently online but aren’t sending HSTS headers are filtered out of Mozilla’s derivative list. Since the inclusion rules are different we end up with two distinct lists.

The HSTS RFC mentions preload lists briefly but doesn’t specify behaviour. So neither the Chromium nor Mozilla approach is wrong. But the lists have several thousand discrepant domains. To me, the Mozilla behaviour feels more true to the standard as it doesn’t require nonstandard directives and you’ve got to keep the HSTS headers active, or else the HSTS preload will drop.

The disagreement between the lists causes an inconsistent security posture on Chrome and Firefox. A site operator may think they enjoy HSTS preload protections, while it actually varies by browser. Chromium runs a website that checks if domains are on the preload list. Mozilla doesn’t have an equivalent. This may perpetuate the misunderstanding that there’s only one HSTS preload list.

What other domains are impacted? I ran a diff between the Mozilla preload list and the Chromium preload list. There are a ton of domains in the output that aren’t currently online and the vast majority appear to be niche websites. Few scream high-profile targets, so their presence on the preload list is questionable. After all, the HSTS header offers great protection on its own; the preload list only protects against the bootstrap man-in-the-middle vulnerability. Does the (currently offline) marketing website for a bed and breakfast really need to be on the preload list?

Who needs HSTS preload?

Certain websites are highly targeted to the point that any exposure to HTTP or bogus TLS certificates causes measurable harm. There are some related improvements, like HTTPS-only mode in browsers, that partially mitigate some of the same problems HSTS is trying to support. But HSTS preload provides full coverage whereas others apply only partially.

Do we need 100k domains on the preload list? Certainly not.

The public-suffix list, another list hardcoded in web browsers, has minimum user count requirements for addition. The public-suffix list requirements state that “projects not serving more than thousands of users are quite likely to be declined” although enforcement appears to be based on self-reporting. The HSTS list enforces no such policy, so there are likely many domains with very low usage.

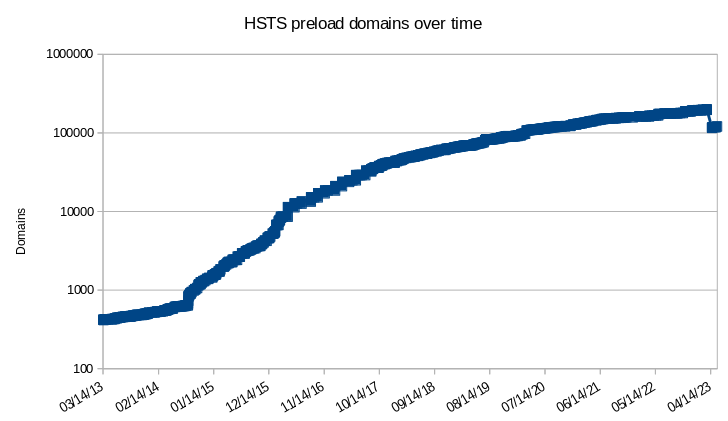

Preload growth rate

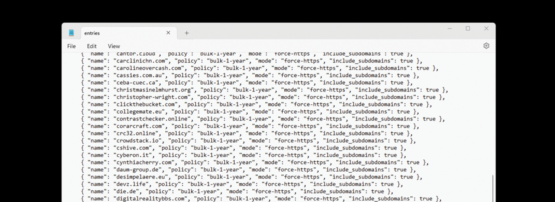

Just how fast is the HSTS preload list growing? Since the preload list is stored in GitHub I’m able to look at the history to pull out some statistics:

- A total of 229k domain names have ever been preloaded.

- 108k of those have been removed (47%).

- The largest removal was on 21 April 2023 removing 82k domains.

- One entry was removed because the entire ccTLD is discontinued: google.tp.

Figure 1 shows the HSTS preload domain count over time, showing a troubling growth rate and the recent large drop (log scale):

Removing unneeded domains

The majority of domains removed on 21 April 2023 currently show negative whois checks. A sample of .com domains shows 84% are no longer registered. A domain that isn’t registered has no owner, so the HSTS policy can reasonably be reset. There’s some minor concern about temporary lapsed domains, but a delay before removal can mitigate that.

Removed entries often belong to services that provide free subdomains, like: *.ddns.net (126 removed), *.azurewebsites.net (93 removed), *.herokuapp.com (57 removed), and *.duckdns.org (28 removed). It seems like these subdomains shouldn’t have been added to the list, as subdomains can no longer be added, but they are domain names too. Each of these domains is on the public-suffix list, which indicates that child domain names are owned by different entities, so each should be handled as a domain name and be able to set their HSTS policies independently.

Future

HSTS is a valuable technology and protects against real-world attacks. HSTS preload is a niche security feature that even Big-Tech companies are slow to adopt and consider as an optional defence-in-depth measure. Concerns about the size of the list have already triggered restrictions on the addition of new subdomains and cleanup efforts.

I suspect HSTS preload will have reduced importance in years ahead as features like HTTPS-only mode become more widely deployed. The list will continue to grow, however, as it’s easy to add new domains. I suspect the list will eventually adopt more restrictions to slow growth and avoid including domains that don’t need it.

Robert Alexander (Mastodon) is a freelance software developer and security consultant interested in software, the cloud, and security.

Adapted from the original post on Robert’s blog.

Discuss on Hacker NewsThe views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.