Back in September 2018, a group of authors submitted the first IETF draft of a document discussing Internet Protocols and the Human Rights to Freedom of Association and Assembly. It is now up to its 11th version.

This is an important topic, too complex to summarize in a short blog post, and bound up in fundamental human rights discussions that have been ongoing in a formal sense since the United Nations (UN) first started exploring a universal charter of human rights in 1947.

Of particular interest in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are Articles 19 and 20, establishing that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” and that “Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.”

If we spin forward 70 years, the extension of human rights to the Internet is widely accepted with UN Human Rights Council affirming in 2012 (PDF) that “… the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online …”

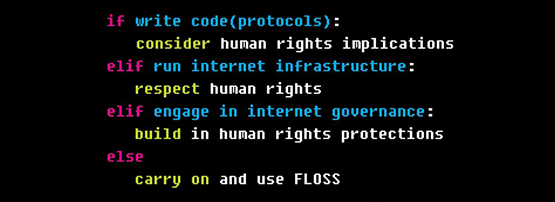

As a logical progression of this line of thinking, carried into the modern Internet-dependent era, the IETF Working Group (WG) has been working on the technical issues we need to understand for the technology of protocols to support fundamental human rights.

The abstract of this current version-11 of the IETF draft is a good indication of the questions here:

Abstract

This document explores whether there is a relation between the Internet architecture and the ability of people to exercise their rights to peaceful assembly and association online. It does so by asking the question: what are the protocol development considerations for freedom of assembly and association? The Internet increasingly mediates our lives, our relationships, and our ability to exercise our human rights.

As a global assemblage, the Internet provides a public space, yet it is predominantly built on private infrastructure. Since Internet protocols and architecture play a central role in the management, development, and use of the Internet, we analyze the relation between protocols, architecture, and the rights to assemble and associate to mitigate infringements on those rights.

This document concludes that the way in which infrastructure is designed and implemented impacts people’s ability to exercise their freedom of assembly and association. It is therefore recommended that the the potential impacts of Internet technologies should be assessed, reflecting recommendations of various UN bodies and norms.

Finally, the document considers both the limitations on changing association and impact of “forced association” in the context of online platforms.

draft-irtf-hrpc-association-11

I’ve reformatted this abstract into four sections because I think it’s worth discussing them individually.

The relationship between the Internet architecture and the ability of people to exercise their rights to peaceful assembly and association online

The first section of their intent poses the leading question — is there any demonstrable linkage between Internet architecture and protocols, protocol development, and the fundamental human rights question? At one level, this is a bit of a rhetorical question, but for all that, it’s a good one. If you are in a minority who believes ‘no, there is no necessary linkage here’ then probably you would want to question the assumptions that stem from the proposition. If (like me) you are in the probable majority who think this is unquestionably true, you want to try and understand the linkages and the consequent costs and concerns.

The Internet provides a public space, yet it is predominantly built on private infrastructure.

So, either pro- or anti- the proposition, this is an area of work where the question needs to be put and understood.

This is another key point, which goes to the continuing tension in the regulation of the Internet as public communications. Much of the last 55 years has been a story of telecommunications deregulation, the relaxing of state monopoly controls on telephony and related services, and the introduction of a competitive market in the provision of communications services worldwide, which both proceeded and leveraged the emergence of the Internet protocol and its related services.

So, it is hardly surprising that almost every aspect of the Internet we engage with is delivered as a private industry activity. Not that there are no government networks or government computing services — there are plenty! But many of these are, in fact, implemented on top of commercial services in the cloud, or through leasing agreements with private carriers. The public space of old, rights to association and communication that used to vest through state telephone and postal services, now vest in … private hands.

The way in which infrastructure is designed and implemented impacts people’s ability to exercise their freedom of assembly and association.

At first glance, there isn’t an obvious linkage between a protocol to the freedom of association, but it should be clear to anyone that how we write code influences how it works. If we write code to assume a Network Address Translation (NAT) and use an intermediary system to rendezvous with another party, then we cannot claim to have independent end-to-end communication in private — the intermediary is bound to what we do.

If we write systems to use an encryption method like Transport Layer Security (TLS) but it ‘leaks’ information about the exact service name we connected to, we cannot connect to services without intermediaries along the path of IP packets knowing who we connected to, even if the actual contents wound up as private end-to-end. If we use the DNS and don’t have access to query minimization, then several intermediary systems will know the full DNS name we asked for, as the distinct domain elements are resolved. So, there is a clear and strong linkage between how we design Internet communication, and at least some aspects of public freedom, including privacy, and under filtering, even access at all. The draft, therefore, rightly identifies the need to at least understand and consider the impact of the protocol on the UN charter obligations.

Finally, the document considers both the limitations on changing association and the impact of ‘forced association’ in the context of online platforms.

This one particularly interests me, because it is about something I personally experience outside of my Internet/IETF-facing roles. My own home is in a co-managed, self-managing apartment complex bound up in a ‘body corporate’. The body corporate meets regularly to decide how we wish to live and has a management function that is outsourced to a commercial entity.

In times past, we had agreements to post paper notices in the lifts and on noticeboards we bought and managed. Now, the commercial entity wants us to use an App and has already indicated that a Facebook group may become their primary communications channel. Other bodies I work with make the same decision. I and my family and friends are, therefore, obligated by circumstances to engage in a specific social media forum for functions we used to manage on paper.

This isn’t just something confined to the social sphere. Governments are increasingly demanding a presence online to provide mandated basic services. For a generation who did not grow up with a keyboard in their pram, this can be isolating, alienating, or even impossible to bridge. For individuals who are under-employed, unemployed, poor or otherwise disadvantaged, it can be an insurmountable barrier to accessing vital services. If you care about privacy or made a conscious decision to disengage from social media (as I have), this is a forced obligation to participate in an online service I have repudiated.

For all these reasons, and because of the fundamental importance, I welcome this work in the IETF, and I hope the authors continue. The draft is extremely well researched and documents its sources. It is being written with care and is worth reading and engaging with even if you disagree with it (as I suspect some do). However, the subject matter is too important to ignore.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.