Large-scale phishing attacks remain a key threat to Internet users and organizations, both due to the direct harm these attacks can cause, such as identity theft or account compromise, and other collateral damage, such as risks due to password reuse across services or simply the necessity of mitigations.

The number of live phishing websites continues to grow and has reached record levels in recent months according to Google Safe Browsing. Phishers have also been exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic to devise new and effective types of lures.

The opportunity to profit with relative ease is a key motivating factor for phishers. This opportunity is enabled by the wide availability of ‘phishing kits’, or all-in-one packages that enable criminals without technical skills to launch attacks.

Over time, as the security community’s anti-phishing efforts improved, so have the techniques of phishing kit authors. But how are attackers able to continue causing damage despite mitigation efforts, and what steps we can take to stop them?

To answer these questions, my colleagues and I at Arizona State University, Samsung Research and PayPal Inc, conducted research to study the anti-phishing ecosystem and developed specialized systems to measure suspected gaps within it. In turn, our measurements led to a number of security recommendations for current and future anti-phishing systems.

Cloaks and lures

The anti-phishing ecosystem provides multiple layers of defence. One of the most direct is browser-based phishing protection.

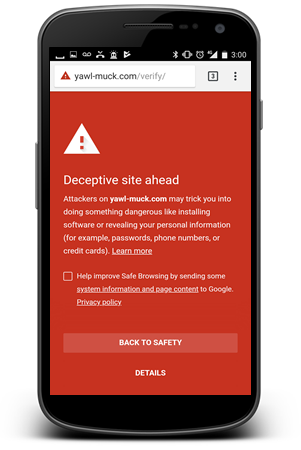

Modern web browsers check blacklists of known phishing URLs and automatically prevent users from viewing their malicious content. This is particularly helpful for protecting users when they have opened link in text messages or emails that slip past spam filters.

However, blacklist warnings only work for URLs detected before the victim’s visit. Simultaneously, phishing kits actively seek to prevent or delay this detection by implementing evasion techniques known as cloaking.

Cloaking aims to make phishing websites appear benign to detection infrastructure and analysts by checking request attributes such as IP addresses, user agents, or the JavaScript environment.

Our team developed an automated testbed, PhishFarm, to empirically evaluate if top anti-phishing entities could effectively detect and mitigate phishing websites with cloaking.

PhishFarm shows anti-phishing tools miss nearly one in five phishing sites

PhishFarm works by deploying a representative sample of artificial (benign but real-looking) phishing websites with chosen types of cloaking, reporting them to entities of interest, and then monitoring major web browsers to see if and when blacklisting occurs.

Based on experiments with over 2,000 websites, we found that all of the tested cloaking techniques delayed blacklisting in some way. Further to this we discovered and subsequently disclosed bugs that prevented mobile browsers at the time (Chrome, Safari, and Firefox) from displaying the intended warnings.

Despite showing that cloaking works, these experiments were not designed to show how well the ecosystem as a whole could detect and block phishing websites. After all, in practice, phishing spam is typically seen by multiple email providers or security vendors. As a result, we adapted PhishFarm to make the reporting process more realistic while also testing combinations of evasion techniques typically used by phishers.

To ensure reproducible results, we repeated our experiments six times over the course of one year. From this we found that although basic phishing pages were detected and blocked in less than an hour on average, those using typical evasion techniques not only took an average of two additional hours to be detected, but also entirely failed to be detected in 19% of cases.

Furthermore, phishing sites with sophisticated emerging cloaking techniques were not blocked at all. Within these gaps, attackers can successfully target potential victims.

Update, analyse, report, repeat

Based on our research findings, we’ve made several recommendations to motivate future anti-phishing efforts across the ecosystem and have disclosed additional gaps specific to individual organizations. The recommendations are as follows:

Improving reporting systems

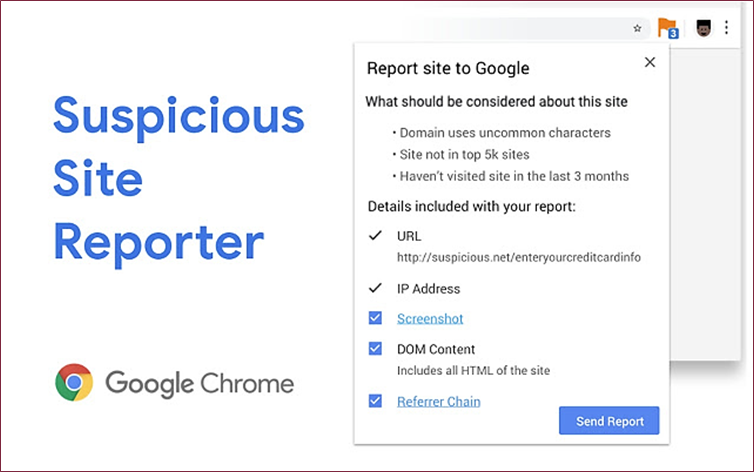

Cloaking helps attackers avoid detection of phishing URLs, so we should work towards improving the robustness of reporting systems and the accuracy of detection systems. Next-generation reporting protocols could include attributes such as IP addresses, redirection chains, or page source to help detection systems successfully verify the malicious content. We found the Google Suspicious Site Reporter to be an effective first step in this direction, and suggest that long-term solutions be easy to access while remaining user-friendly to encourage more reporting.

Quantifying phishing protection

Even though the ecosystem already curates lists of phishing URLs (through organizations such as PhishTank, the APWG, or VirusTotal), it does not track metrics on how quickly and how completely these URLs are blocked after being reported (for example, what PhishFarm was designed to measure).

The monitoring of these metrics, even at the level of attacks targeting individual organizations, can shed light on the effectiveness of an organization’s anti-phishing approach, detect technical bugs, and even help proactively identify emerging threats. Note: monitoring by the PhishFarm framework can extend beyond anti-phishing blacklists to spam filters, browser toolbars, and more.

Scrutinizing redirection links to bypass evasion

Typical evasion consists of email lures with shortened redirection links that go through one or more hops before sending the user to the phishing website. Such links hamper spam filters as they cannot easily be correlated with known malicious landing pages, especially when intermediate hops themselves implement cloaking. Therefore, increased controls should be implemented by redirection link providers, and anti-phishing systems should more robustly scrutinize redirection.

Expanding proactive defences

Attackers eagerly exploit the reactive nature of defences such as anti-phishing blacklists. However, proactive measures such as in-browser heuristic classifiers are comparatively less mature and often still require backends to deliver a final verdict. These measures can help close the detection gap that allows phishing to scale.

Criminals will continue to evolve

Both phishing attacks and defences have evolved significantly since the early days of the Internet. As we work to continue keeping users safe from these attacks, we should also be mindful that criminals evolve quickly, and thus also consider emerging types of scams that might not yet get the same kind of attention by the security community.

Full details on the PhishFarm and PhishTime frameworks, the experiments, and the results can be found in the respective publications.

Adam Oest is a senior cybersecurity researcher at PayPal.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.