Seventy-five years ago, with the creation of the United Nations (UN), the international community started building a system of ‘built-in safety valves‘ that help contain and prevent threats to international stability. Most of these safety measures are based on commonly agreed standards of responsible behaviour, or in other words: norms.

A famous norm from the technical community is the credo of ‘rough consensus and running code’ that guides decision-making by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). In dealing with potential negative effects of Internet-related issues on international security, the UN embraced a similar normative approach.

Cyber norms or rather ‘norms of international cooperation around cybersecurity’ constitute a key component in today’s efforts to foster a safe and secure cyberspace.

There are lots of places where norms with regard to cybersecurity have been developed. A quite complete collection has been collated by the IGF Best Practices Forum on cybersecurity (there was a session by this Best Practices Forum during the global IGF on 17 November).

In this post, I will focus on the 11 norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace that the 193 member states of the UN endorsed in 2015 and look at the role the Internet community can play.

UN norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace

The UN norms have a deliberately narrow focus. They are a means to prevent and mitigate the worst of all cyber incidents: those intentionally or inadvertently perpetrated by states in a context of political-military tensions or economic conflicts.

Therefore, they describe what states should and should not be doing in cyberspace, either directly through government agencies or through collaboration within their domestic Internet communities.

Recently, during the Asia Pacific regional Internet Governance Forum (APrIGF), APNIC triggered a lively online workshop around the question ‘do cybernorms help or hinder incident response activities?’. The speakers unpacked norm #2 about ‘attribution’, that is, the process of considering all relevant information, and reaching a high degree of certainty, before assigning responsibility for an ICT incident to someone, some entity or a government.

But there are other norms where the technical community may have a bigger role to play: in helping improve the protection of critical infrastructure; ensuring supply chain security; and encouraging responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities.

This subset of norms related to ICT security generally receive far less attention in public debates, conferences and in international negotiations; they tend to be less contested or politically sensitive.

Let’s try to deep-dive into one of those norms, like the first part of norm 9 that says “States should take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain so that end users have confidence in the security of ICT products.” This implies a commitment by every responsible government to ensure the confidentiality, integrity and availability of ICT products that end up in their consumer market.

Some people would connect the application of this norm with restrictive measures that some Western governments have taken with regard to their use of services and products from Huawei and Kaspersky. In this case, an economy like Australia did not receive enough reassurances from the respective authorities nor the companies that they would, or could, respect the integrity of data and equipment.

In strengthening transparency, accountability and reassurance, there’s a key role to play for the Internet technical community as a neutral, authoritative and non-political community of practitioners.

For instance, an economy could show its commitment to supply chain security (or to the protection of critical national infrastructure) by endorsing an initiative like the Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security (MANRS) and actively encouraging adoption of common routing security measures by network operators registered on its territory. The same goes for other initiatives around mail security or IPv6 adoption.

Another example is the little-known Common Criteria initiative. It was established in 1998 by the certification authorities of Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States to mutually recognize each other’s certified products. By now, it has 31 members from economies on different continents, who either certify new products, or simply recognize the validity of these certifications. It’s a good example of international cooperation based on trust, transparency and accountability.

These good practices often occur well below the radar of policy folk, diplomats and the media; and they occur regardless of the success of negotiations in UN working groups. But it is important to feed these examples into regional, global and inter-governmental policy discussions so that we create broader awareness and build stronger accountability. With that, we can tackle those attempting to undermine the stability of the global network.

Likewise, the success of any of the norms taking hold in our communities relies on the public sector being able to bring industry, civil society organizations and the Internet technical community together in a collegial and cooperative environment.

#UNCyberNormsChallenge

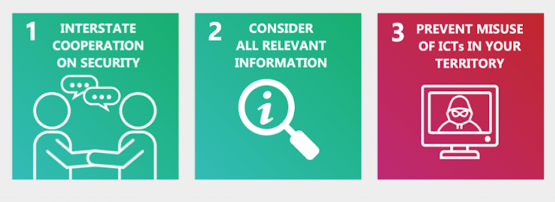

I’m currently directing a cyber capacity building project at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (with support from the UK and Australian governments) to increase general awareness of these UN norms. We recently released a set of graphic materials for the global community to use in training, presentations, research and awareness-raising efforts.

As a next step, we are composing a repository of examples of what these high-level norms comprise in practice, in particular in the Asia Pacific. Based on training activities conducted so far in the Asia Pacific region, we see that a lot of interesting work across the region is already taking place, some by national Internet communities, other parts by governments and industry.

That’s why we launched the #UNCyberNormsChallenge; a campaign encouraging all stakeholders to share what they consider good national, regional and/or global practices in advancing international cybersecurity.

Bart Hogeveen is Head of Cyber Capacity Building at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.