Domain Name System (DNS) latency is a key component to having a good online experience. And to minimize DNS latency, carefully picking DNS servers and anonymization relays plays an important role.

But the best way to minimize latency is to avoid sending useless queries to start with. Which is why the DNS was designed, since day one, to be a heavily cacheable protocol. Individual records have a time-to-live (TTL), originally set by zone administrators, and resolvers use this information to keep these records in memory to avoid unnecessary traffic.

Is caching efficient? A quick study I made a couple of years ago showed that there was room for improvement. Today, I want to take a new look at the current state of affairs.

To do so, I patched an Encrypted DNS Server to store the original TTL of a response, defined as the minimum TTL of its records, for each incoming query. This gives us a good overview of the TTL distribution of real-world traffic, but also accounts for the popularity of individual queries.

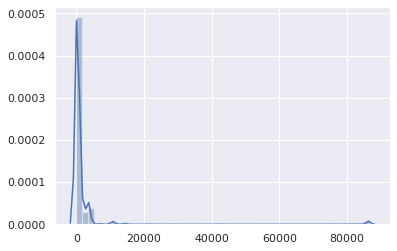

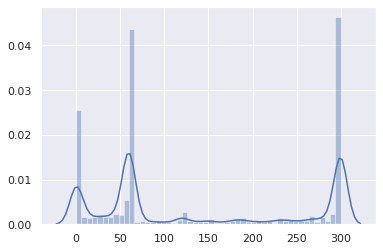

That patched version was left to run for a couple of hours. The resulting data set is composed of 1,583,579 (name, qtype, TTL, timestamp) tuples. Here is the overall TTL distribution (the X axis is the TTL in seconds):

Besides a negligible bump at 86,400 (mainly for SOA records), it’s pretty obvious that TTLs are in the low range. Let’s zoom in:

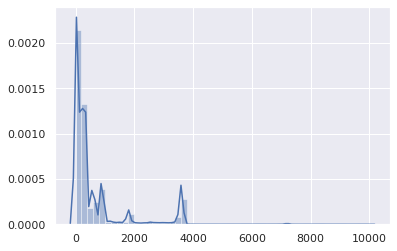

Alright, TTLs above 1 hour are statistically insignificant. Let’s focus on the 0-3,600 range:

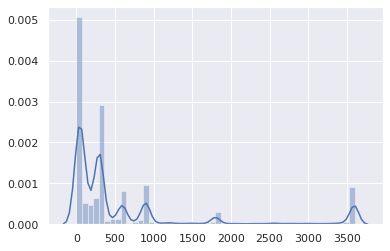

And where most TTLs sit between 0 and 15 minutes:

The vast majority is between 0 and 5 minutes:

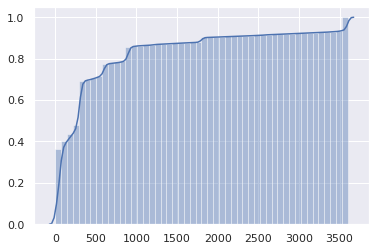

This is not great. The cumulative distribution may make the issue even more obvious:

Half the Internet has a 1-minute TTL or less, and three-quarters have a 5-minute TTL or less.

But wait, this is actually worse. These are TTLs as defined by authoritative servers. However, TTLs retrieved from client resolvers (for example, routers, local caches) get a TTL that upstream resolvers decrement every second. So, on average, the actual duration a client can use a cached entry before requiring a new query is half of the original TTL.

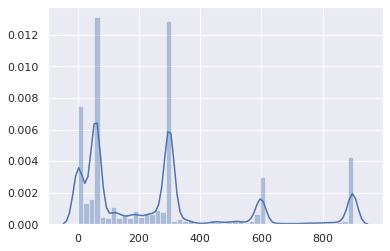

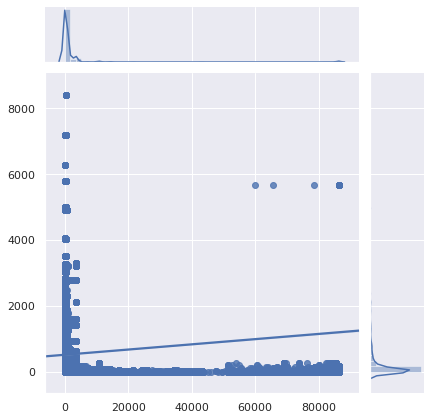

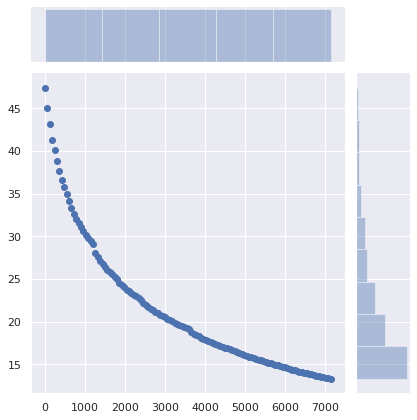

Maybe these very low TTLs only affect uncommon queries, and not popular websites and APIs. Let’s take a look:

Unfortunately, the most popular queries are also the most pointless to cache. Let’s zoom in:

Verdict: it’s really bad, or rather it was already bad, and it’s gotten worse. DNS caching has become next to useless. With fewer people using their ISP’s DNS resolver (for good reasons), the increased latency becomes more noticeable. DNS caching has become only useful for content no one visits. Also, note that software can interpret low TTLs differently.

Why?

Why are DNS records set with such low TTLs?

- Legacy load balancers are left with default settings.

- The urban legend that DNS-based load balancing depends on TTLs (it doesn’t).

- Administrators wanting their changes to be applied immediately, because it may require less planning work.

- As a DNS or load-balancer administrator, your duty is to efficiently deploy the configuration people ask, not to make websites and services fast.

- Low TTLs give peace of mind.

I’m not including ‘for failover’ in that list, as this has become less and less relevant. If the intent is to redirect users to a different network just to display a fail whale page when absolutely everything else is on fire, having more than one-minute delay is probably acceptable.

CDNs and load-balancers are largely to blame, especially when they combine CNAME records with short TTLs with records also having short (but independent) TTLs:

$ drill raw.githubusercontent.com raw.githubusercontent.com. 9 IN CNAME github.map.fastly.net. github.map.fastly.net. 20 IN A 151.101.128.133 github.map.fastly.net. 20 IN A 151.101.192.133 github.map.fastly.net. 20 IN A 151.101.0.133 github.map.fastly.net. 20 IN A 151.101.64.133

A new query needs to be sent whenever the CNAME or any of the A records expire. They both have a 30-second TTL but are not in phase. The actual average TTL will be 15 seconds.

But wait! This is worse. Some resolvers behave pretty badly in such a low-TTL-CNAME+low-TTL-records situation:

$ drill raw.githubusercontent.com @4.2.2.2 raw.githubusercontent.com. 1 IN CNAME github.map.fastly.net. github.map.fastly.net. 1 IN A 151.101.16.133

This is Level3’s resolver, which, I think, is running BIND. If you keep sending that query, the returned TTL will always be 1. Essentially, raw.githubusercontent.com will never be cached.

Here’s another example of a low-TTL-CNAME+low-TTL-records situation, featuring a very popular name:

$ drill detectportal.firefox.com @1.1.1.1 detectportal.firefox.com. 25 IN CNAME detectportal.prod.mozaws.net. detectportal.prod.mozaws.net. 26 IN CNAME detectportal.firefox.com-v2.edgesuite.net. detectportal.firefox.com-v2.edgesuite.net. 10668 IN CNAME a1089.dscd.akamai.net. a1089.dscd.akamai.net. 10 IN A 104.123.50.106 a1089.dscd.akamai.net. 10 IN A 104.123.50.88

No less than three CNAME records. Ouch. One of them has a decent TTL, but it’s totally useless. Other CNAMEs have an original TTL of 60 seconds; the akamai.net names have a maximum TTL of 20 seconds and none of that is in phase.

How about one that your Apple devices constantly poll?

$ drill 1-courier.push.apple.com @4.2.2.2 1-courier.push.apple.com. 1253 IN CNAME 1.courier-push-apple.com.akadns.net. 1.courier-push-apple.com.akadns.net. 1 IN CNAME gb-courier-4.push-apple.com.akadns.net. gb-courier-4.push-apple.com.akadns.net. 1 IN A 17.57.146.84 gb-courier-4.push-apple.com.akadns.net. 1 IN A 17.57.146.85

The same configuration as Firefox and the TTL is stuck to 1 most of the time when using Level3’s resolver.

What about Dropbox?

$ drill client.dropbox.com @8.8.8.8 client.dropbox.com. 7 IN CNAME client.dropbox-dns.com. client.dropbox-dns.com. 59 IN A 162.125.67.3 $ drill client.dropbox.com @4.2.2.2 client.dropbox.com. 1 IN CNAME client.dropbox-dns.com. client.dropbox-dns.com. 1 IN A 162.125.64.3

safebrowsing.googleapis.com has a TTL of 60 seconds. Facebook names have a 60-second TTL. And, once again, from a client perspective, these values should be halved.

How about setting a minimum TTL?

Using the name, query type, TTL and timestamp initially stored, I wrote a script that simulates the 1.5+ million queries going through a caching resolver to estimate how many queries were sent due to an expired cache entry. 47.4% of the queries were made after an existing, cached entry had expired. This is unreasonably high.

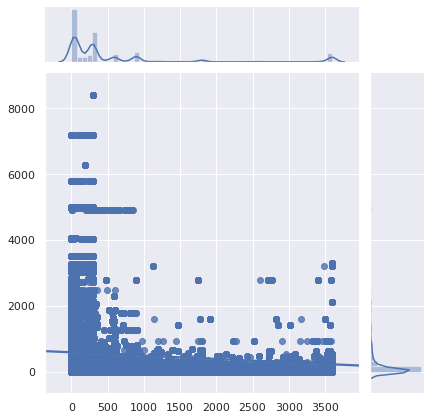

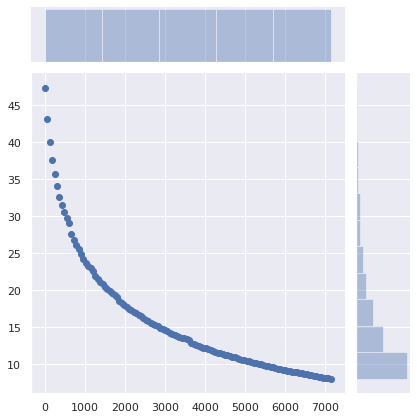

What would be the impact on caching if a minimum TTL was set?

The X axis is the minimum TTL that was set. Records whose original TTL was higher than this value were unaffected. The Y axis is the percentage of queries made by a client that already had a cached entry, but a new query was made and the cached entry had expired.

The number of queries drops from 47% to 36% just by setting a minimum TTL of 5 minutes. Setting a minimum TTL of 15 minutes makes the number of required queries drop to 29%. A minimum TTL of 1 hour makes it drop to 17%. That’s a significant difference!

How about not changing anything server-side, but having client DNS caches (routers, local resolvers and caches…) set a minimum TTL instead?

The number of required queries drops from 47% to 34% by setting a minimum TTL of 5 minutes, to 25% with a 15-minute minimum, and to 13% with a 1-hour minimum. 40 minutes maybe a sweet spot. The impact of that minimal change is huge.

What are the implications?

Of course, a service can switch to a new cloud provider, a new server, a new network, requiring clients to use up-to-date DNS records. And having reasonably low TTLs helps make the transition friction-free. However, no one moving to a new infrastructure is going to expect clients to use the new DNS records within 1 minute, 5 minutes or 15 minutes.

Setting a minimum TTL of 40 minutes instead of 5 minutes is not going to prevent users from accessing the service. However, it will drastically reduce latency, and improve privacy (more queries = more tracking opportunities) and reliability by avoiding unneeded queries.

Of course, RFCs say that TTLs should be strictly respected. But the reality is that the DNS has become inefficient.

If you are operating authoritative DNS servers, please revisit your TTLs. Do you really need these to be ridiculously low?

Read: How to choose DNS TTL values

Sure, there are valid reasons to use low DNS TTLs. But not for 75% of the Internet to serve content that is mostly immutable, but pointless to cache. And if, for whatever reasons, you really need to use low DNS TTLs, also make sure that cache doesn’t work on your website either. For the very same reasons.

If you use a local DNS cache such as dnscrypt-proxy that allows minimum TTLs to be set, use that feature. This is okay. Nothing bad will happen. Set that minimum TTL to something between 40 minutes (2400 seconds) and 1 hour; this is a perfectly reasonable range.

Adapted from original post which appeared on 00f.net

Frank Denis is a fashion photographer with a knack for math, computer vision, opensource software and infosec.

Discuss on Hacker NewsThe views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

I just read an article saying that reducing TTL is harmless 🙂

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224243237_Reducing_DNS_caching

The article on TTL reduction is talking about loads on internal DNS servers. Those queries are client queries made over UDP to corporate or other DNS servers, querying internal DNS records used for internal hosts. In that environment a low TTL is beneficial since the clients may be DHCP assigned IP addresses or they may be mobile where their IP address is rapidly changing. Since applications like Microsoft Active Directory use dynamically created DNS records for hosts on the internal network, a low TTL keeps things accurate. This post is talking about EXTERNAL dns serves which are serving names to the general Internet of websites and other hosts where the IP address hardly ever changes.

DNS is not that difficult a concept to understand once you wrap you brain around it. But you will NOT learn it with a diet of Youtube videos and 2000 word articles that take 15 minutes to read. Before attempting to post a rebuttal to an article, learn what you are talking about.

Most domains these days are hosted on the cloud. Your provider can change the IPs used for a CloudFront geography at any time. In such a scenario, how can you have a higher TTL?

Nice article – has some very good points!

Except for failover…

Failover is the best argument for low TTL. A smooth failover is impossible without a very low TTL and that’s the end of the story.

And I’m not talking about something ridiculous like failover with the intent of showing an error page but failover to keep your service reachable.

Not to mention it has virtually no downside.

When you have a a planned failover approaching, you lower the TTL in a few gradual increments as the failover time approaches, then after the new service is in place and stable, increase the TTL back to an hour or whatever.

Planned failover, sure, what about actual failover? Do you also exptect to be notified several hours upfront? XD

Palo firewalls have a ‘feature’ of being able to use URL’s to build ACL’s (useful when some sites use multiple ip’s or change their ip address). The firewall manages this by polling the names every 15 minutes and generates a table ip -> name mapping. For TTL’s of less than 30 minutes, this feature becomes useless due to intermittent dropping of traffic when the ip’s change. We’re still hopeful Palo will allow the Polling interval to be changed to a lower value.

Really? A UDP query will return around half a kb or so of data, even if you in the extreme would require every request for a hostname to be prefixed with a query to the authoritative server, this really should not be a problem at all for that service. Yes of course you want to do some caching, but a cache invalidation of 30 seconds is perfectly reasonable for such a low amount of data over the network. Especially if the potential consequence of not doing so is having a connection hanging for the timeout you suggest, this can easily have cascading failure consequences, as proven by a lot of outages that have DNS failures at their root and take hours to recover.

Oh boo hoo the clients are seeing extra delays of tens of milliseconds. Like they’ll notice when the webpages usually take many magnitudes longer due to being heavy laden with videos, images, javascript and ads.

For example if a client uses Google’s DNS (e.g. 8.8.8.8 ). Google has many servers all over the world so in most cases that’s within tens of milliseconds away, and if it’s a popular DNS query it’ll be cached most of the time.

In contrast the users are more likely to notice if one day their clients kept using the wrong IP for 40 minutes as per your proposal.

Ha, I use a TTL of 1 week! I assume that I’ll have a week’s notice before I need to make any major changes. I can reduce the TTL temporarily need needed and then put it back afterwards. 🙂

lol, and furthermore lmao

it is 2022 my dude, we can afford low ttls to allow for more responsive disaster recovery and failover. imagine the facebook bgp outage but they were out for an entire week because they used a long ttl. the company would be donezo

The way of measuring this affects (and skews) the outcome. DNS queries with low TTLs are requested more frequently and because of that, you are seeing more of them pass through your patched DNS relay, which you only left running for a few hours instead of for at least the max TTL you wanted to measure.

“oh boo hoo”

“lmao”

“it is 2022 my dude”

Yeah, some quality engineers here — I’ll be paying atention to _them_…

Accurate description of the problem by author. Thanks for the mention of dnscrypt-proxy. The usual commercial software we have just can’t do that, whereas typically OSS easily can. 🙂

I set a low zone ttl in order to avoid ridiculous delays of a day or more in propagating throughout the world. I set it back manually. A simple fix would be an automatic management feature to set the ttl low for a fixed amount of time, then set it high again. The low TTL would “push” changes out to the world.

Some of the worst offenders are some of the biggest users. Add some feedback mechanism to standards committees and industry coalitions and these TTLs are likely to come down. Another solution is to stop dismissing DNS communication upstream. A web developer knows that they have changed their DNS Zone and need it propagated to all users of that Zone. Surely an efficient way to ‘push’ a zone forward to all active resolvers can be invented?! After all, it would only be used once each time full propagation is wanted, not constantly, the way TTL is implemented.