The Domain Name System (DNS), which resolves domain names into IP addresses for browsers and other applications, serves as one of the most fundamental Internet components.

Unfortunately, almost all DNS packets are sent unencrypted at present. This design makes DNS traffic vulnerable to snooping and manipulation, which is widely considered as one of the Internet’s biggest bugs. For example, in the real word, some unscrupulous Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are exploiting this for error traffic monetization, redirecting customers whose DNS lookups fail to advertisement-oriented web servers.

To prevent unexpected behaviours of rogue DNS resolvers, a lot of Internet users switch from their local resolvers to popular public DNS services, such as Google Public DNS (8.8.8.8), by manually configuring their applications and operating systems.

Interception is common, particularly for Chinese users

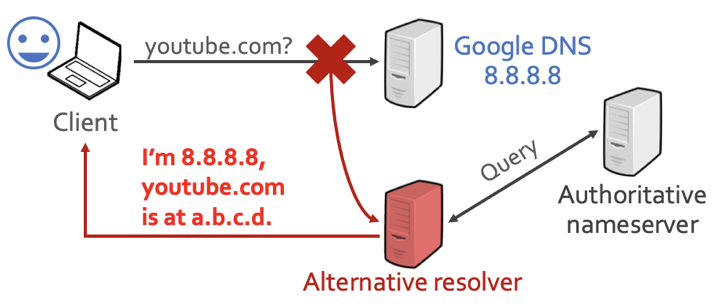

However, have you ever considered when you use Google DNS as your resolver, whether your queries may be answered by somebody else? Such as an uninvited middleman, who may answer your queries with alternative resolvers, and spoof the IP addresses of your public DNS resolvers to make it real? This kind of hidden interception behaviour results in privacy and security issues, and breaks the trust relationship between Internet users and public DNS resolvers.

Figure 1 — Google DNS traffic can be intercepted via middleboxes.

So, in order to understand and characterize this security problem, my colleagues and I at Tsinghua University decided to look for uninvited middleboxes, by designing a novel approach that leverages 148K residential and cellular IP addresses around the world. Specifically, we narrowed down our study on querying self-registered domains, to avoid the influence of network censorship mechanisms.

As a result, among all 3,047 Autonomous Aystems (ASes) that we investigated, DNS queries in 259 ASes (8.5%) were found to be intercepted — interception policies varied according to different types of DNS traffic. Surprisingly, 27.9% of DNS requests over UDP from China to the Google Public DNS were intercepted. Also, we found the Google Public DNS appears to be a particularly popular intercept target — 82 ASes are intercepting more than 90% of DNS requests that were supposed to reach Google.

From the view of Internet users, not all intercepted DNS queries had been modified yet; but it’s possible. We observed that some DNS responses from the Google Public DNS were tampered with in AS 9808 (Guangdong Mobile), by pointing our own domain to a web portal that promotes an app of China Mobile.

As for the potential interceptors, besides ISPs, they also include network operators, firewalls, malware, enterprise proxy devices, and antivirus software. We should note that not all interceptors are malicious.

See our paper, ‘Who Is Answering My Queries: Understanding and Characterizing Interception of the DNS Resolution Path’ presented at USENIX Security Symposium 2018 and the Domain Name System Operations Analysis and Research Center (DNS-OARC) 2019 and Applied Networking Research Workshop (ANRW) 2019.

Authenticate resolvers to protect against middlemen

As for the solution to this problem, we believe the key point is to authenticate the resolvers that you are using, via encrypted DNS mechanisms.

As a side note, Nick Sullivan, the head of cryptography at Cloudflare, says that this study is a great motivator for the deployment of encrypted DNS and DNSSEC.

Currently, a set of DNS encryption techniques have been proposed, such as DNS-over-TLS (RFC 7858) and DNS-over-HTTPS (RFC 8484), and the deployment of DNS encryption is promising. In May 2019, 8% of DNS queries to Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 were encrypted via DNS-over-TLS or DNS-over-HTTPS, according to Matthew Prince (CEO of Cloudflare).

8% of queries to @Cloudflare‘s 1.1.1.1 (https://t.co/IiThafhOhR) are now encrypted via DNS over TLS or DNS over HTTPS. #betterinternet pic.twitter.com/ktNXQk9eyz

— Matthew Prince 🌥 (@eastdakota) May 24, 2019

Baojun Liu is a Ph.D candidate of Tsinghua University, advised by Prof. Ying Liu and Prof. Haixin Duan. His research interests include DNS security and the underground economy.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.