Much has been said about the effects of DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH), a new protocol that has spurred heated discussions in the DNS, web and ISP communities.

Sara Dickinson gave a good description of the issues, and Bert Hubert recounted the different views from the panel that happened at FOSDEM, Europe’s biggest free software meeting. In this post I will focus on what I think is the key problem, and the questions that we should try to answer.

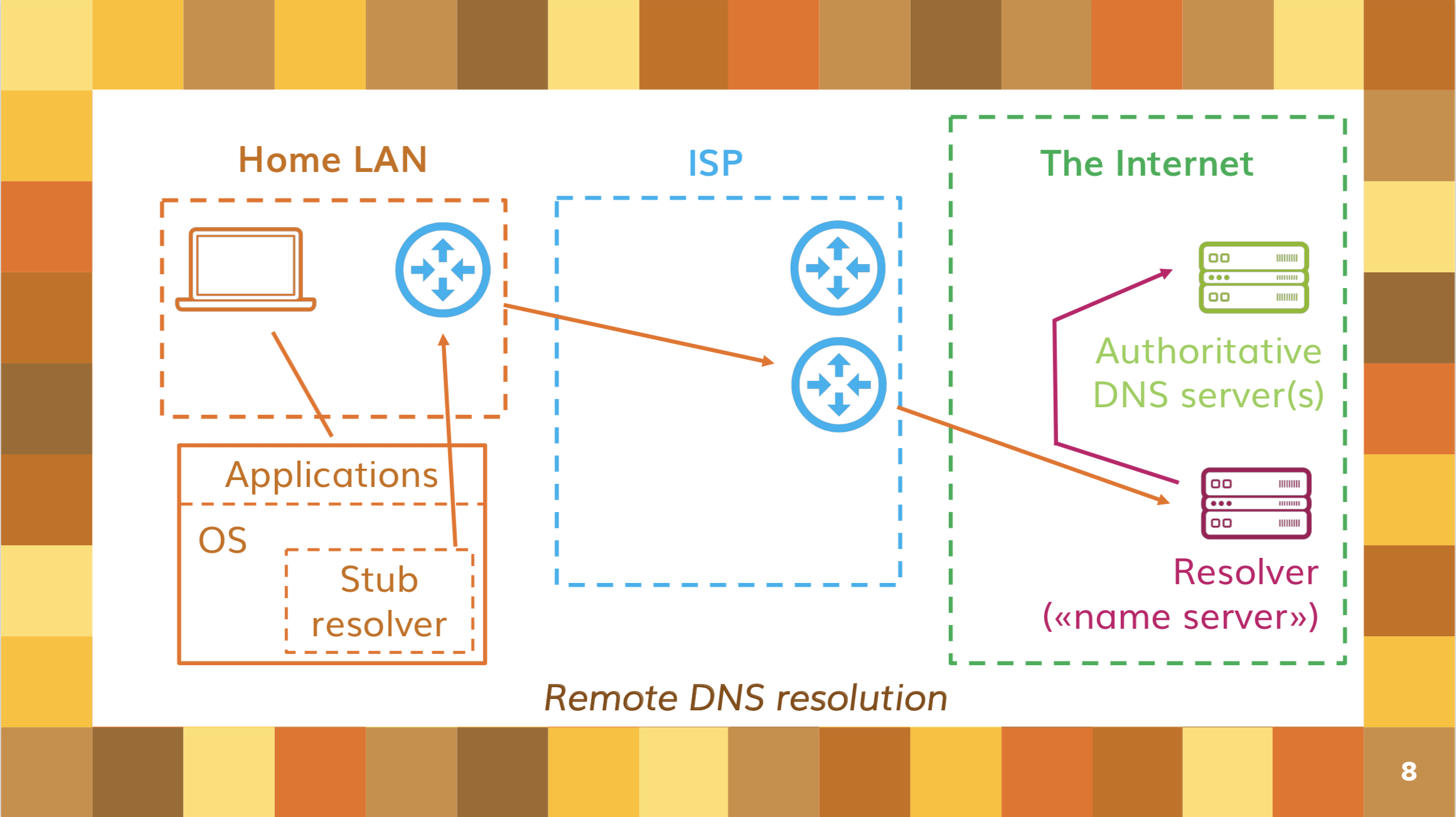

Most of the issues created by DoH derive from the fact that it promotes a basic architectural change in the way domain names are resolved by Internet users. Until now, the default has been to use a local resolver, provided on your local network (or immediately near to it in topological terms) by whoever is giving you Internet access.

Over time, remote resolvers, located somewhere over the Internet and controlled by someone other than your ISP, appeared as an alternative; Google’s 8.8.8.8 and Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 are among the best known. Remote resolvers have always been an alternative to the default resolver; an alternative that could be chosen, with some kind of system configuration action, by those users that cared about where their DNS queries were going.

Figure 1 — The remote DNS resolution model.

DoH is actively changing the default, making the use of remote resolvers the normality, and possibly changing their ‘market share’ from around 10 to 20% to an overwhelming majority.

Its proponents insist that this is the effect of the deployment model adopted by browser makers, rather than of the protocol itself. This is true, but it is also true that the design choices of the protocol, such as moving the resolution to the application layer — making it easy for applications to implement it by exploiting a widely available protocol such as HTTPS and making it almost impossible for network operators to block the service — seem explicitly designed to promote this effect, no matter what the rest of the Internet community thinks.

However, this would not be such a problem if the choice of browsers were not so limited; estimates vary, but the most used browser (Google Chrome) has over 60% of the market, and three others (Apple, Microsoft and Mozilla) control another 30%. If the application chooses the resolver (at least as a default) or acts as a gatekeeper that decides who can be allowed to provide DoH resolution to its users, then most resolutions for the web will end up being controlled globally by very few companies, all under a single jurisdiction.

But even if this centralizing effect were not so marked, we will have to live with much less choice and much less distribution than we have today. Currently, DNS queries are spread across hundreds of thousands of resolvers all around the planet; with DoH and its ‘DNS-over-cloud’ deployment model, it is likely that only a handful of big players will serve most of the world.

This is not how the DNS or the Internet were meant to be, and given how crucial the name resolution service is — without it the Internet doesn’t work, and its operator can track everything you do online and even redirect or block your destinations — many are worried by this outlook.

Even those who care about privacy are worried; DoH encrypts your connection and this is good, but if all your DNS traffic ends up in the hands of one of a few global companies that already know everything about you and are in the business of selling your information to advertisers, then you will have less privacy than before.

Figure 2 — When it comes to privacy, encrypting transport is not the biggest issue.

So, how do we address this risk?

Here comes what I call the ‘DoH dilemma’: who should choose the resolver that you use?

Until now, there has always been an agreement: your access provider will suggest you its own resolver as a default when you connect. However, if you don’t like it, you, the user, can pick any resolver you like in your device’s configuration.

The model suggested by Mozilla is radically different: since most of its users are not technical, and since they want to position their browser as the most privacy-friendly of the lot, they will choose the default resolver for their users. And they will make sure, via contractual agreements, that it will not sell user data. It is unclear if Mozilla, in the final implementation, will let you freely change the resolver; apparently, they plan to maintain a list of global ‘trusted resolvers’, deciding who else, if any, can be allowed onto that list, and only letting users pick from that list.

But there are other players that would like to have a say in which resolver you use. ISPs, for example, would like you to use one of their resolvers, because they monitor the DNS traffic to defend the health of their network, detect botnet infections, stop threats and provide you value-added services such as parental control; but also, in some parts of the world, because they exploit your personal information as well. Many governments and courts want to have a say in the policies applied by the resolver, because they want to block access to a lot of content for a lot of reasons, and the DNS is the best control point for doing that with a reasonable balance between maximizing effectiveness and minimizing disruption.

With this in mind, the DoH dilemma has two parts to it: first, who should choose the resolver; second, who should decide its policies. The second part leads to more questions, for example: when is DNS query mangling appropriate? Which economy has sovereignty over a person’s DNS queries? Is ‘my network, my rules’ an appropriate principle? Who decides what is censored and what is not?

A complex discussion long overdue

In the end, DoH brings under the spotlight an architectural issue whose discussion is long overdue. Originally, the DNS was designed so that all resolvers would give the same reply to the same query everywhere to everyone, as a simple distributed database. However, that has not been true for a long time now, as more and more use cases (mostly unrelated to governmental censorship; things like split horizon, local names, botnet blocking, safe browsing for children, and even CDNs come to mind) have relied on a specific resolver giving you a customized reply. The DNS is not a distributed database any more, but rather a complex localized service with many additional requirements, relying heavily on who you are and which resolver you use; any change in the resolver will break a lot of things. How do we take this into account when introducing changes to the way the DNS works?

This is a complex discussion that mixes technical, policy and legal aspects, and some politics too; it is neither easy nor immediate. But this is the discussion that we need to have.

Vittorio Bertola is Head of Policy and Innovation at Open-Xchange.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Great explanation