As I was preparing my keynote presentation for the recent UK IPv6 Council AGM held in London earlier this month, it occurred to me that I’ve spent a significant amount of time talking about how good IPv6 is at these and other meetings, often to those who are already championing and using the protocol. So, I’m writing it down and sharing it with a wider audience, notably those who are using common misconceptions as reasons for not deploying IPv6.

Misconception #1: It’s been 25 years and only a quarter of the Internet is using IPv6, it should be abandoned

About a month ago, I came across an article that talked about IPv6 being a failure and should be abandoned due to it taking 25 years to reach 25% deployment. What struck me the most was the reference to it having been 25 years.

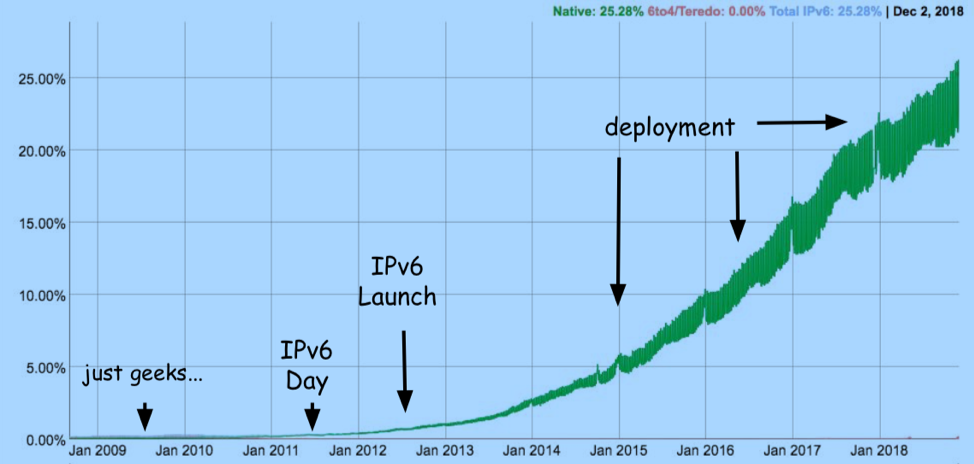

If you look at Figure 1, it’s obvious that IPv6 was dormant (non-existent) until IPv6 World Day in 2011 and the IPv6 World Launch in 2012. These two events really kickstarted the concerted push for IPv6 — not only its deployment but content delivered by it. As such, I’d say it has not been 25 years but six or seven years, at the most.

Figure 1 — IPv6 adoption graph. Source: Google

One might argue that even 25% adoption is still not impressive in this time frame. Well, there is one thing to remember here: 25% is an average adoption rate across the whole Internet, and many of you realize there is no such thing as a homogeneous Internet. The Internet comprises millions of different kinds of networks with their own drivers and challenges on the road to IPv6 adoption. As such their experiences will vary.

For example, there are enterprises and financial networks that are very conservative, with a long hardware/software life cycle, happily hiding behind a single public IPv4 address. These networks are in no hurry to deploy IPv6 even though some have started moving slowly in the right direction.

On the other side of the spectrum mobile networks, which have a huge and rapidly increasing number of clients, cannot continue to hide behind layers of NAT. Apple measurements show that for cellular networks, 44% of all connections globally are made from an IPv6-enabled network; in the US that number is almost double. In other words: half of all mobile devices are IPv6 enabled and if you are in the US, there’s almost a 90% chance that your phone has IPv6. Instances like this make it hard to believe that IPv6 should be abandoned because no one is using it.

Read: The Mobile Internet: Home of IPv6

Misconception #2: “I don’t need IPv6”

For those who read the section above and recognize that IPv6 is being deployed by multiple networks but believe it is and won’t be relevant for your network, let me try to convince you otherwise.

We’ve been talking about ‘why you might need to deploy IPv6’ for years; IPv4 address scarcity and issues caused by NAT are all well known. However, there are some other reasons for you to consider deploying IPv6.

First, let me tell you a story.

About 12 years ago, when I was working for a network equipment vendor, I was talking to a customer about a shiny new wireless solution that included centralized management and wireless controller access points providing not just Wi-Fi but also allowing location tracking using triangulation. “Oh no!” said the customer. “We do not need all that weird stuff. We are happy with our Cat5 cables. Besides, it must be very insecure and would allow anyone to connect to our network!”.

The truth was they had wireless network features deployed already but in a totally uncontrolled and very insecure manner. Their employees were bringing their own access points creating ad-hoc networks because it was convenient for them; more so than being locked to an ethernet plug. But all these things were discovered later when the customer decided to deploy the wireless network and started to monitor the environment.

Now, what does this have to do with IPv6? Well, the same principle applies: if the mountain won’t come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain. If you won’t come to IPv6, then IPv6 must go to you (and you might not even notice). Most modern switches and routers have IPv6 enabled and so have end hosts (laptops, mobile devices). As soon as you connect two such devices to the same network, they are now able to communicate over IPv6.

Networks that are intended to be IPv4-only might (and most likely will) be lacking IPv6 security features, which leads to accidental service disruptions and deliberate attacks. The most obvious example is a rogue device that sends router advertisements, making itself an IPv6 default router for all IPv6-enabled devices on the link. While Happy Eyeballs would provide a quick fallback to IPv4, if a rogue router is just a plain misconfiguration, the intentional attack could easily result in a connectivity outage or a man-in-the-middle attack scenario. You can find more details on this topic here: RFC 7123, Security Implications of IPv6 on IPv4 Networks.

Read: Happy Eyeballs – promoting a healthy IPv4 and IPv6 coexistence

For those who care more about serving content to users, IPv6 might bring some benefits too. To serve content you need DNS, which in turns means that DNSSEC might (or shall I say should?) be of interest to you. There is one problem with DNSSEC though: it does not work very well for IPv6-only validating clients and DNS64. It’s 2018 (almost 2019) and it’s a bit late to say ‘don’t deploy NAT64/DNS64 networks’ for that ship has sailed; there are millions and millions of IPv6-only devices in mobile networks. Therefore, if you deploy DNS, you should deploy DNSSEC and if you deploy DNSSEC you should also enable IPv6.

There is another compelling reason for IPv6 adoption: allegedly it might be faster than IPv4, at least in some economies. APNIC measurements look quite positive and Akamai reported that for US mobile clients IPv6 is 10% faster than IPv4.

Check back tomorrow for four more misconceptions.

Jen Linkova is a Network Engineer at Google and Co-Chair of the RIPE IPv6 Working Group.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Fantastic article! #IPv6

0) This is an Interesting article. However,

1) Misconception #1: the author appears extrapolating the internal (Google) information as worldwide statistics.

2) Here is a more general data that is updated about every 15 minutes. It is a far cry from what the author is relying upon.

https://ams-ix.net/technical/statistics/sflow-stats/ether-type

3) The above Ams-Ix statistics is an ongoing activity originated in September 2012 on IPv6 Launch Day. So, it should have enough credibility in this respect. See Page 11/13 of the following.

https://www.slideshare.net/MaximTuliuk/amsix-ipv6-launch-day

4) Misconception #2: The fundamental impedance to IPv6 deployment probably is due to its decision to ignore the fundamental engineering discipline of backward compatibility to IPv4.

Regards,

Abe (2018-12-20 09:10)

Hi Abe,

Thanks for the comments!

> Misconception #1: the author appears extrapolating the internal (Google) information as worldwide statistics.

Well, as I said, there is no such thing as Internet. It’s like white light: if you look closely you’ll many different colours. I’m looking at it from the service/network owner perspective. If you have a web-site – how much of your users will come to you over Ipv6?

There are other data sources:

APNIC data shows slightly lower numbers (https://stats.labs.apnic.net/ipv6) but the trend would be still the same. Akamai statistics is worth looking for: there are countries when majority of users are using v6.

Here is the CloudFlare data: https://blog.cloudflare.com/98-percent-ipv6/ which shows, again, that numbers might vary significantly between networks.

> Here is a more general data that is updated about every 15 minutes. It is a far cry from what the author is relying upon.

>https://ams-ix.net/technical/statistics/sflow-stats/ether-type

Oh this is very interesting. I’m not sure what’s going on there and it looks like there are not many IXes publishing per-protocols traffic stats (at least those I randomly checked). So I found data for MSK-IX: https://www.msk-ix.ru/en/traffic/ only…

Off top of my head: the Internet is getting more and more centralized. You can almost say ‘20% of sites generate 80% of traffic’. And those large content providers would most likely have direct peerings with large eyeballs networks – and those eyeballs networks are more likely to deploy IPv6. Therefore it’s entirely possible that significant portion of IPv6 traffic avoids IXes.

Just a theory made before my first coffee…But the very good point and I think I now have an idea for some research, thanks! 😉

> Misconception #2: The fundamental impedance to IPv6 deployment probably is due to its decision to ignore the fundamental engineering discipline of backward compatibility to IPv4.

I’d agree that would have made the deployment a bit easier (however IMHO the cost would be too high) but I’m not sure it’s a fundamental critical factor.

IMHO people just do not deploy a new technology until they see benefits. And until recently IPv6 benefits were more like mid- and long-term which means a decision maker needs to see themselves in the same company for extended period of time. So those who are not deploying IPv6 now are not seeing benefits.

Hi, Jen:

0) Appreciate your thoughts.

1) “Peering”: Yes, the basic consequence of peering is to reduce the traffic through the IXs. However, a recent article disclosed a behind-the-scene issue of IPv6 having trouble to get peering among major carriers settled down. The “Game of IPv6” section of the following article reported that IPv6 peering was not quite agreed upon as IPv4. Thus, a larger portion of the IPv6 traffic than desired was going through IX’s which should make the IPv6 portion of the AMS-IX statistics bigger. This counters the theory that you are trying to develop:

https://blog.usejournal.com/national-internet-segments-reliability-survey-df8129b47743

2) To follow your lead, allow me to tell a true story. When I was growing up as a young person curious about technology, I was fascinated by how telephone worked. However, I only could sense the constant improvements of the performance, without knowing when, what and how changes were made. Upon getting into the industry, I was amazed by the ranges and vintages of equipment that made up the PSTN (Public Switched Telephone Network). This applied to not only the physically visible hardware, but also there were so many software versions that were in the field with periodical major releases called “generics”. They all worked in harmony to an ordinary consumer’s experience. Yet, no one talked about “backward compatibility”, except worked hard to make sure that the service upgrades were done through practices called “hot-cut-over during mid-night”. This is totally opposite to the manner that the Internet has been trying to upgrade from IPv4 to IPv6. Had IPv6 started with the finite goal of expanding the IPv4 address pool, the transition would have been achieved “quietly” from end-user point of view. Then, all performance improvements could be done gradually under IPv6 without alerting the “outsiders”. Certainly, there will be no need to make it a big deal of relying marketing pushes. As far as cost, since there has been no parallel deployment of another technology path, there is no way to make honest comparison. But, there may be something coming to make this possible (See Pt. 4) below.)

3) I know the above is kind out of the blue for you. To be fair, I should give you a full disclosure of where I came from. You may look up my LinkedIn profile to get some idea:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/chen-abraham-b7a918/

4) Also, our team went through a lot of study to come up with an unexpected solution to IPv4 address depletion related issues. In the process, we studied so many angles of the Internet that it is hard to describe here.

https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-chen-ati-adaptive-ipv4-address-space-04

5) To make the story short, I have read your follow-up four misconceptions, but feel that they are details consequential to these first two. So, I would not comment on them, but do invite you to debate with me, perhaps offline (through LinkedIn or IETF Draft) to avoid burdening the general readers, of these two nearly philosophical topics.

Happy Holidays,

Abe (2018-12-20 23:39)

Well-written article, albeit a bit hypocritical, because Google Cloud still doesn’t have proper IPv6 support, unlike all the other big providers.

Same goes for Google’s Firebase. It uses Fastly, which does support IPv6, so it should be fairly easy. In fact, one can add the corresponding AAAA records to a Firebase hosted website and it works just fine over IPv6. But during certificate renewal, Firebase won’t even try to renew if there are *any* AAAA records – even if they’re the right ones. Furthermore, Let’s Encrypt is used for certificates, which does support certificate renewal over IPv6, so that’s not the problem.

And for cdn.firebase.com it’s simply necessary to change the CNAME from f6.shared.global.fastly.net to dualstack.f6.shared.global.fastly.net.

Very interesting read, thank you very much!

The Other Reason for slow deployment of IPv6 is subscribers are reluctant to change the IPv4 Modems/ CPEs. Already using subscribers will think that why one should go for IPv6 when they are already comfortable with IPv4. Buying of IPv6 compatible Modems/ CPEs is extra cost for subscribers/ ISPs.