This is the second of three posts describing CERT Australia’s experience in deploying an automated platform for cyber threat intelligence sharing, discussing lessons learned and exploring future opportunities. Read the first one here.

The need for sharing actionable and tactically useful indicators has long been understood. A range of significant efforts have been made in this space with regard to standards for formatting data in a normalised form, and platforms for managing trust groups for distributing this well-formatted data. Notable projects include:

- The incident object description exchange format (IODEF: RFC 5070)

- The collective intelligence framework (CIF)

- Open indicators of compromise framework (OpenIOC)

- The Bro intelligence framework

- Open threat exchange (OTX)

- Malware information sharing platform (MISP)

In recent years, and at the time when CERT Australia began increasing its capabilities for sharing niche cyber threat intelligence with key partners across the country, the Mitre Corporation’s efforts on structured threat information expression (STIX) and trusted, automated exchange of indicator information (TAXII) were prominent.

A number of factors influenced CERT Australia’s decision in 2013 to base our cyber threat intelligence sharing efforts around these standards, including: a rich vocabulary based on cyber observables (Cybox), a range of constructs within STIX that allowed more than just the sharing of indicator lists with limited context; and actively developed python bindings to allow us to engage in our own development activities.

In addition to the sound conceptual foundations of Cybox, STIX and TAXII, the fact that other governments, CERTs and the financial services sector information sharing and analysis centre (FS-ISAC) were successfully using this technology gave us a high degree of confidence that this was not yet another standard that would lead to security vapourware.

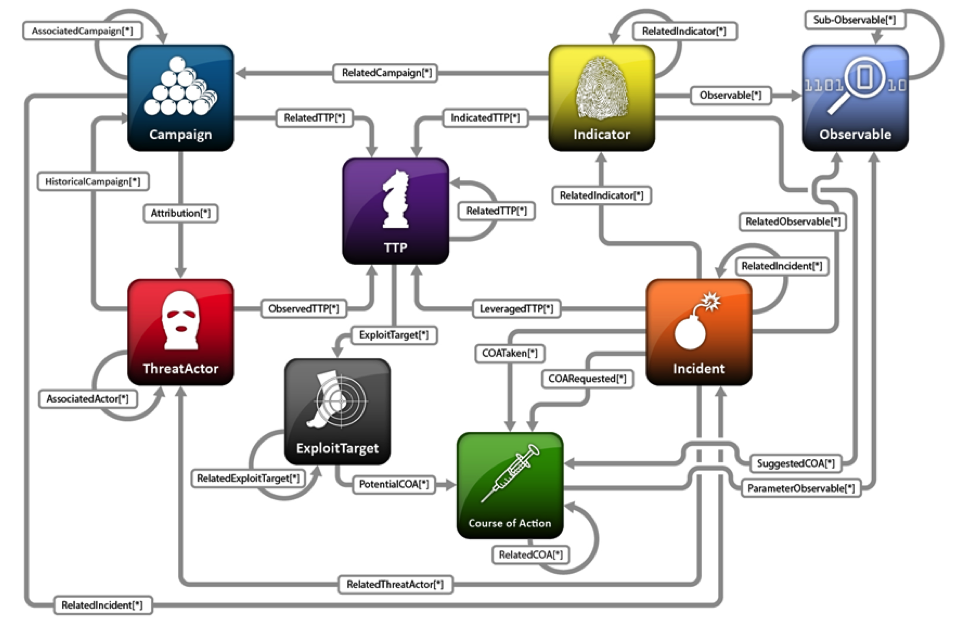

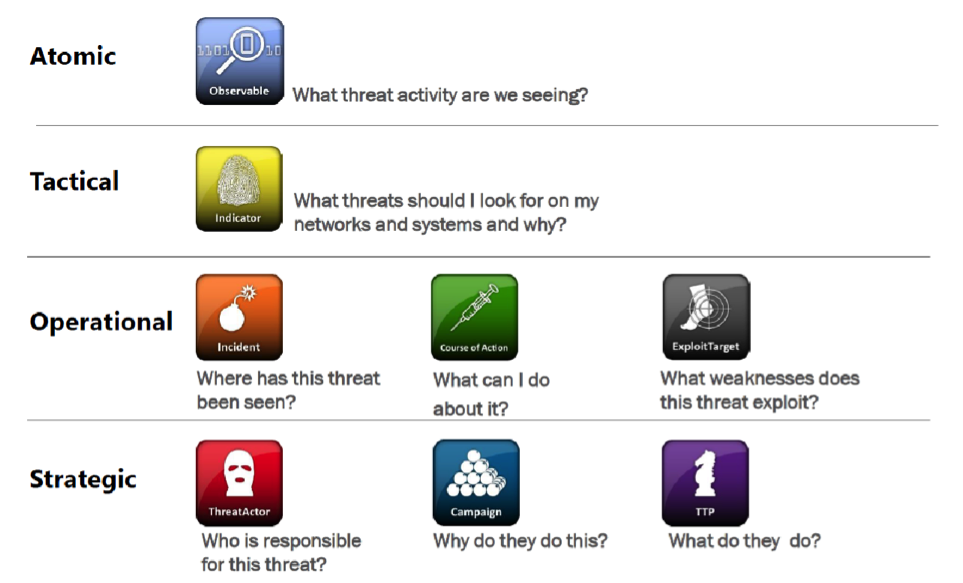

Constructs supported in structured threat information expression (STIX)

It is instructive to have a high-level look at the constructs contained within STIX and how they can support security operations (Figure 3 and 4 below).

STIX incorporates eight high-level constructs that define malicious adversary behaviour at the tactical, operational and strategic levels. As such, it is both an effective representation for network defence and security intelligence and analysis.

Well formed STIX packages will not only detail what you should be looking for on your network, in logs, etc. but also what the broader context this activity may represent with an assertion of confidence.

As a national CERT with responsibility for providing detailed advice on actions to take while simultaneously protecting equities, the inclusion of explicit course of action (CoA) information within packages is a great advantage.

We look forward to seeing further innovation in this space, with a range of intuitive and usable tools for generating well-formed and detailed STIX packages available for the masses.

Working with industry partners to make STIX and TAXII data available

At the start of 2015 when we commenced the automated sharing of STIX packages via TAXII, two things quickly became apparent:

- support for authenticated TAXII in a range of security platforms was nascent

- it was not sufficient for organisations to merely transport indicators from our premises to theirs – they needed to also consider how to integrate this new intelligence into their security operations workflow.

On the first issue, we invested time in understanding the products partners used, engaging with vendors to advocate for support for the standards and authentication mechanisms required.

Where we encountered new platforms in use by partners, we would work with them to establish connectivity. Then, based on that experience, we would develop a configuration guide to ease the connection process in the future. We are very thankful for the support we received from industry and vendor partners on this. We now have detailed configuration guidance for numerous products and we can get industry partners up and running in a few hours.

CERT Australia has been generating STIX packages since January 2014 and automatically distributing these to partners via TAXII since January 2015. In that time, we have been able to validate that STIX is sufficiently expressive to model malicious activity in a pragmatic way.

In some ways, STIX is too expressive: much of our efforts have gone towards identifying the common use cases we encounter, and standardising a mechanism for how we will structure our packages.

The Mitre Corporation has undertaken some excellent work to provide exemplary idioms for common use cases – anyone considering generating STIX will find these invaluable.

When we embarked on this journey, we assumed that the commercial market would respond strongly with a range of tools to support CERTs and industry to both generate and consume STIX formatted cyber threat intelligence. While this certainly is the case for the latter, limited commercial options for generating STIX packages with the degree of fidelity we require has meant we have had to develop and maintain internal tools for this.

While this makes sense for national CERT, where the effort expended in generating high-quality packages is amortised across a large partner base, this will not be the case for everyone. However, the longevity of STIX and TAXII will be dependent on the ratio between producers and consumers being maintained at a sustainable level. STIX production can be encouraged through the creation of easy to use tools.

Putting cyber threat intelligence into practice

On the second issue, we are soliciting feedback from partners on how they are using automatically exchanged STIX packages and sharing their successes with others.

In recent ransomware campaigns, we are pleased to report that indicators related to this activity are released each morning and our partners have been able to automatically add these to watch and block lists, successfully preventing compromise when other controls such as mail gateways fail to effectively block this content. While this is a simplistic example, we expect defensive tradecraft to evolve quite rapidly, in line with the higher quality threat intelligence we can share.

In one instance a partner, based on tradecraft identified in a series of STIX packages and some independent investigation, was able to ascertain that a specific type of mailer script was always associated with the delivery of a particular type of malware. The adversary tradecraft was to compromise poorly secured websites and add this mailer script for later use in malware delivery – by quarantining all email with header information matching this mailer script, they were able to essentially kill a class of activity targeting their network without maintaining an ever growing list of IP addresses, domains, subjects, senders and attachments to block.

Importantly, as actions based on shared cyber threat intelligence are automated, there is the prospect that scarce security resources in an organisation will have time to focus on more sophisticated activity targeting the organisations they work for. However, there is also a real opportunity for misadventure.

The inadvertent inclusion of legitimate and critical Internet infrastructure in a STIX package could cause significant impacts. Those generating cyber threat intelligence need to be sure that indicators are appropriately annotated with a confidence level, and that consumers of such packages understand that what the presence of a set of observables is indicative of. For example, if Facebook or another legitimate domain is being used for communications check by a piece of malware, blocking this is somewhat pointless, but understanding this does have value as an attribute in distinguishing one malicious campaign from another.

In my third and final post in this series, I will describe the cyber threat intelligence toolkit we have developed in an effort to make these tool above more user-friendly for our industry partners.

Jason Smith is the Technical Director of CERT Australia, Australia’s national computer emergency response team.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

I’ve put together this tool which might be useful for anyone delving into the world of STIX2, as it can be very difficult to follow best practices, especially with large JSON files. Simply paste your JSON and receive output on any errors, missing elements or formatting issues.

https://stixvalidator.com