Thomas Daniels, Maarten Bosteels, Sebastian Castro, Moritz Müller, Thymen Wabeke, Thijs van den Hout, Maciej Korczyński, and Georgios Smaragdakis contributed to this work.

Phishing attacks, which trick users into sharing private data, have been a major security threat for years. According to a 2023 FBI report, it is the top digital crime type. In Europe, ENISA states in its 2023 report that “phishing is once again the most common vector for initial access”.

In a recent peer-reviewed paper, researchers from DNS Belgium, SIDN Labs, .IE Registry, University of Grenoble Alps, Delft University of Technology, and I carried out a longitudinal study characterizing phishing attacks observed at three European ccTLDs — the Netherlands’ .nl (managed by SIDN), Ireland’s .ie (managed by the .IE Registry), and Belgium’s .be (managed by DNS Belgium).

While the ancient Romans loved to mix various fish to create the infamous fish sauce called Garum, we instead combined more than 28,000 phishing domain names with the goal of improving the registries’ detection and mitigation policies — the largest study to date. Let’s dive into our findings.

ccTLDs compared

The ccTLDs we evaluate in this study have different characteristics, as shown in Table 1.

- Number of domain names: We see a large variation in the number of domain names (330k for .ie, to 6.1M to .nl).

- Registration policies: .nl and .be have open registration, meaning anyone can register domain names under their zone, whereas .ie has a restricted registration policy — only individuals and businesses related to Ireland can register domain names.

The differences shown in Table 1 are taken into account during our analysis.

| ccTLD | Registration policy | Domains | Population |

| .nl (Netherlands) | Open | 6.1M | 17.5M |

| .ie (Ireland) | Restricted | 330.1k | 4.9M |

| .be (Belgium) | Open | 1.7M | 11.5M |

Phishing datasets

Table 2 presents the phishing datasets we evaluated for each ccTLD. The phishing URLs were obtained from Netcraft, a commercial phishing blocklist provider used by all our registries. Each registry has only access to domain names in their respective ccTLD and possesses access to historical data. There are other phishing blocklists, and we evaluated a second one in the paper — however, we chose Netcraft in our paper for its coverage and low false positive rates.

| .nl | .ie | .be | |

| Starting date | 16/9/2013 | 30/7/2019 | 29/8/2019 |

| Ending date | 5/6/2023 | 25/8/2023 | 5/6/2023 |

| Period | ~10 years | ~4 years | ~4 years |

| Domains (SLDs) | 25,389 | 555 | 2,810 |

| URLs | 137,880 | 4,542 | 27,346 |

Do ccTLDs matter when choosing who to impersonate?

ccTLDs are closely tied to their economies, with governments, individuals, and businesses frequently using them for their domain names. In a way, a ccTLD can be seen as a brand, and humans assign trust levels to brands. We explore whether attackers exploit this trust for phishing attacks.

Table 3 shows that for the three ccTLDs most of the impersonated companies are international rather than based in the ccTLD’s economy. For instance, we see phishing attacks targeting Asian and African banks using .nl domains, and Microsoft is the most frequently impersonated company across all three ccTLDs. These domains cover up to 78 economies and span 114 market segments, indicating that ccTLDs are being used for global impersonation.

| .nl | .ie | .be | |

| Targeted companies | 1,057 | 206 | 546 |

| Local | 58 | 8 | 33 |

| International | 942 | 198 | 460 |

| Unknown | 57 | 0 | 53 |

| Companies’ economies | 78 | 18 | 64 |

| Market segments | 114 | 52 | 108 |

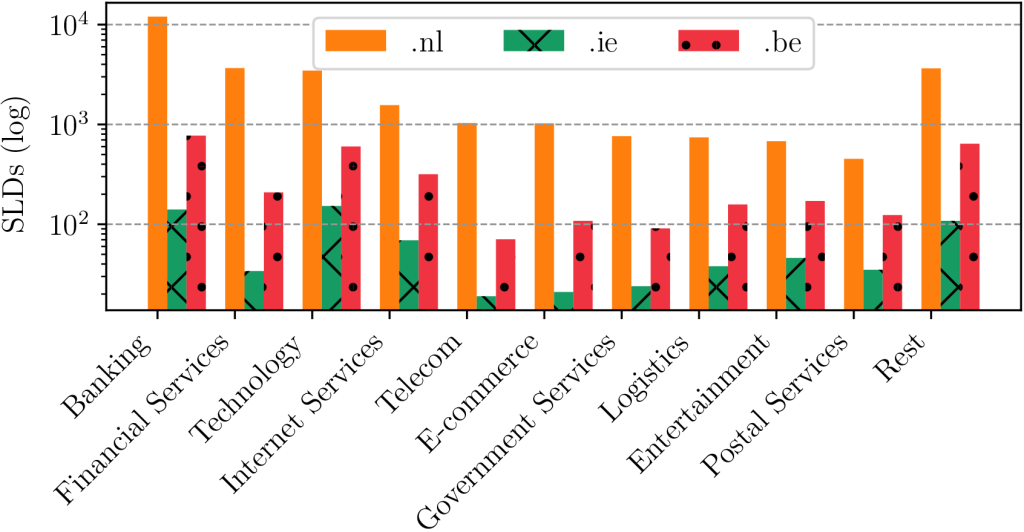

Figure 1 highlights the most targeted market segments in ccTLDs, based on the number of Second-Level Domains (SLDs). Banking and financial services top the list across all three ccTLDs. Interestingly, these segments were also offered by LabHost, a phishing-as-a-service provider that was shut down in April 2024.

One might conclude that attackers don’t care which ccTLD they use for phishing attacks. But is that really the case?

Two attack strategies

That doesn’t hold up to close scrutiny when considering the domain name’s age at the time of the phishing notification. A clear pattern emerges for both the .be and .nl ccTLDs — new domains tend to target national companies, while older domains are used to target international companies.

Why is there such a clear difference?

We hypothesize that there are two distinct attack strategies:

- Attackers impersonating national companies prefer to register and host their own domains given they can choose domains that sound like the legit ones, for example, revalidate-card-bank.nl. A domain name like this, which has the same ccTLD as the original one from the bank, in the local language (Dutch for the Netherlands), has a higher chance of successfully deceiving users than if it was hosted on a domain like flowershop.jp, which has a different TLD and not banking keywords.

- Attackers impersonating international companies — at least the ones we see in .nl and .be — are indifferent to the ccTLD. They prefer to compromise someone else’s website, given it’s a free resource in order to carry out their campaigns (previous research has shown that websites are often scanned for CMS vulnerabilities). For these attackers, it doesn’t matter if the domain is flowershop.jp when impersonating a South African bank or an American credit union.

This distribution boils down to the attacker’s choice. They either pay for a domain name, hosting, and DNS service to get a cherry-picked name, or go cheap and use someone else’s resources?

As Table 4 shows, 20% of phishing attacks use new (maliciously registered) domain names, targeting less than 5% of companies, mostly local. Meanwhile, 80% of attacks use old (likely compromised) domain names, targeting most companies.

| Maliciously registered | Compromised domains | |

| Use | Local company or operating locally | Any, mostly international |

| Share SLDs | 20.00% | 80.00% |

| Targeted companies | < 5% | >95% |

Table 5 shows the economy of origin of impersonated companies, for both .nl and .be.

| .nl | Companies | SLDs | Median age (days) |

| All | 1,054 | 26,740 | 1,641 |

| NL | 58 | 6,084 | 2.5 |

| .be | |||

| All | 546 | 2,810 | 2,154 |

| BE | 33 | 254 | 2 |

But what about .ie domain names? Why doesn’t this apply to them? .ie has a restricted registration policy, which prevents attackers from easily registering new domains for abuse (though they have done so in the past using forged documents). This policy effectively inhibits phishing attacks using new domains but, unfortunately, doesn’t help with compromised domain names.

Takeaway: Phishers can be classified into two groups based on the domain names they use:

- Local attackers: Prefer to register new domains to target national companies.

- Other attackers: Use any domains to target companies elsewhere.

For our ccTLDs, most attacks actually use old, likely compromised domain names.

Comparing targeted brands across ccTLDs

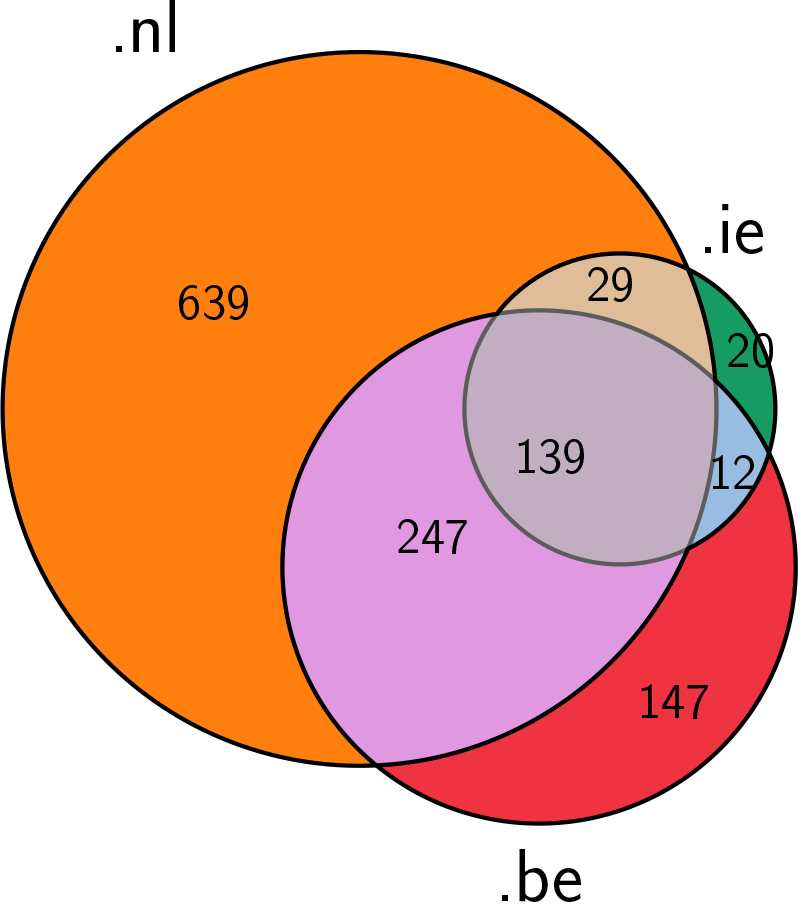

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the brands impersonated in each ccTLD.

In Figure 5, we can observe that 139 companies, representing 11% of the total, are found across all ccTLDs. These include global Internet giants like Microsoft, Google, Netflix, and PayPal, which account for 58% of all second-level domains (SLDs) used in attacks. Additionally, 247 companies are impersonated using both .nl and .be domains. The cultural, linguistic, and financial ties between the Netherlands and Belgium likely explain why companies often operate in both economies, making .nl and .be domains attractive for impersonation. The remaining companies appear randomly. The .nl domain has 639 more companies targeted than the others, likely due to its larger attack surface (with 6.1 million domain names) and the use of nearly 10 years of data, compared to just four years for the other ccTLDs.

Mitigation

Phishing mitigation can occur at the DNS or web application levels, or both. At the DNS level, the domain name used in phishing can be deleted from the namespace and from the zone file. It can also be suspended, where it is deleted (‘delisted’) from the DNS zone but not from the namespace. Lastly, it can remain in the zone and namespace but have its authoritative DNS servers (NS records) changed to a safe server. At the web level, it can simply be removed from the website.

Each ccTLD has its own abuse mitigation policy (see .nl and .ie for complete policies).

If a phishing attack is confirmed, for new domain names:

- .be: Suspends the domain as soon as possible.

- .nl: Notifies other parties (registrar, hosting provider, and so on) and waits 66 hours. If it is not fixed, the domain is suspended.

- .ie: Does not suspend, as most phishing involves compromised domain names that can be fixed with web mitigation.

We examined the mitigation of phishing domain names for the ccTLDs.

So, the type of domain name also influences how it is mitigated:

- Old, compromised domains: For all ccTLDs, there is little DNS-level mitigation. Instead, mitigation occurs at the web application level, handled by hosting providers. For example, if your neighbourhood bakery’s website gets compromised and hosts phishing content.

- Newly registered domains: Likely registered by the attacker, these see a mix of DNS and web-level mitigation, depending on the ccTLD. If the domain is maliciously registered, DNS-level mitigation makes sense. For example, santander-card-update.tld is very likely fake and the longer it stays online, the more victims it attracts.

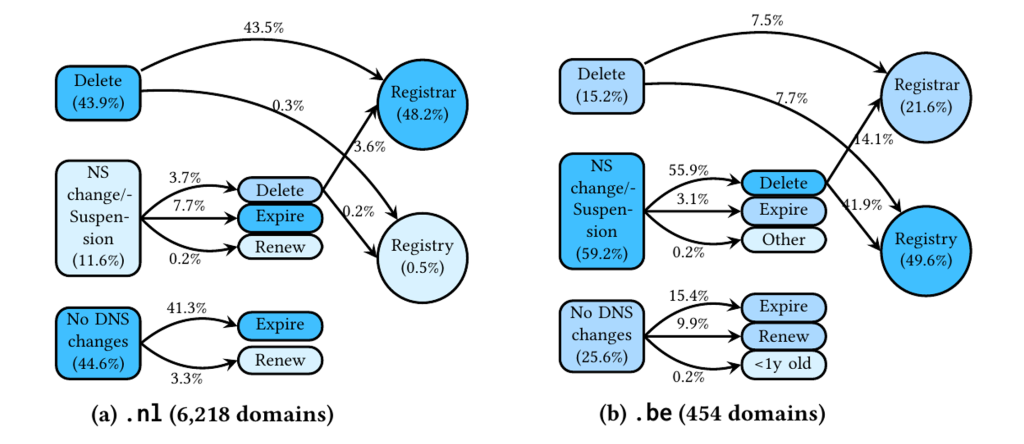

Figure 3 shows the mitigation chain for all new domain names (<7 days old) for both .nl and .be (recall .ie has a restricted registration policy). The impact of the registry’s policy is clear. For .nl:, 55% of maliciously registered domain names are mitigated at the DNS level, mostly by registrars (48.2%), and for .be, 75% of maliciously registered domain names are mitigated at the DNS level, mostly by the registry (49.6%).

In other words, .be actively removes these domains, while .nl relies on registrars to handle most mitigation first.

Mitigation times

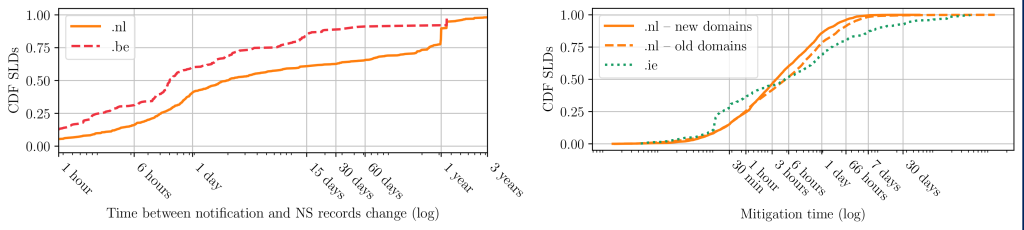

Time is of the essence when mitigating phishing. In Figure 4, the left plot shows that at the DNS level, more than 60% of .be domains are mitigated on the first day, whereas for .nl, that figure is around 40%. However, when considering both DNS and web mitigation together (as reported by Netcraft, available only for .nl and .ie as an extra service), the right plot shows that roughly 80% of domains are mitigated on the first day for .nl, for both new and old domains, and almost at the same rate for .ie.

So, what can we conclude from this? Phishing mitigation is not a single event carried out by one actor. In practice, actions are taken independently by registrars, registries, hosting providers, and webmasters to mitigate phishing attacks. The plot on the right in Figure 4 shows the impact of this collaborative effort — phishing sites are mitigated much faster than they could be by a registry acting alone.

What’s next

Our study is the first to compare abuse across three registries with different registration policies. We have demonstrated the impact of registration and abuse mitigation policies on overall phishing mitigation. Some hackers leverage the ccTLDs’ brand to impersonate national companies, while most attackers act as freeloaders, exploiting others’ resources — specifically, their vulnerable websites.

We propose the following action points from our study:

- More research on compromised domain names: Most research focuses on newly registered domains. We call for action to detect, characterize, and mitigate compromised domains, which constitute the bulk of phishing domains, accounting for 80% of current phishing attacks.

- Revisiting registry policies: The results of this research are being discussed internally at the ccTLDs and may lead to policy adjustments to keep up with attackers’ evolving strategies.

For more details on this research and other results, please refer to the peer-reviewed paper that will appear in the 2024 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS 2024).

Giovane Moura is a Data Scientist with SIDN Labs and an Assistant Profesor at TU Delft.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.