IPv6 deployment has been a challenge in many economies, including Indonesia. In 2018, Universitas Islam Indonesia (UII) started using IPv6 but faced minimal bandwidth usage due to the limited availability of IPv6-based content and infrastructure. However, the landscape has changed, with more global content providers delivering their content via IPv6. Despite this progress, less than 15% of users in Indonesia were using IPv6 as of the last assessment.

UII, consistently a top IPv6 user within the economy, was awarded for its IPv6 achievements by the Ministry of ICT of the Republic of Indonesia in December 2023. The university was working to replicate and improve its IPv6 deployment strategies in sectors such as education and government to accelerate implementation across Indonesia.

The project aimed to deliver IPv6 to end users and organizations with minimal effort, focusing on higher education institutions, research organizations, and government agencies. It proposed intensive workshops on IPv6 and delivered an easy-to-implement, SDN-based solution for distributing IPv6 addresses to address the lack of IPv6 adoption in Indonesia. The project began with workshops and training for engineers, the main targets in deploying IPv6. It then continued with IPv6 deployment, providing tunnel-broker appliances to pilot participants.

During the project, there were at least three significant achievements. Firstly, specialized workshops and training sessions were conducted, engaging 108 participants from 64 institutions and highlighting the keen interest in and the need for IPv6 knowledge across various sectors. Secondly, tunnel broker software was developed and successfully implemented as a proof of concept in some participating organizations. Thirdly, academic research complemented practical efforts, resulting in a paper based on a detailed survey. This paper emphasizes the need for IPv6 workshops to address real-world engineering challenges, such as large-scale IPv6 deployment in enterprises.

IPv6 issues in Indonesia

The problem with the state of IPv6 deployment in Indonesia is multifaceted, with several complicated issues arising from limited implementation. While technically, IPv6 had been successfully established at the level of BGP peering and core routers, it needs to be delivered effectively to end users. Many of the existing deployments only served as proof that IPv6 worked within core networks, but they did not extend to end user devices.

This limited implementation hindered the development of a robust IPv6 infrastructure and the adoption of IPv6 by ISPs and content providers. Moreover, when end clients were not IPv6-enabled, content providers saw no benefits in delivering their content through IPv6. This created a chicken-and-egg situation where content providers hesitated to invest in IPv6 adoption, while end users lacked access to IPv6 content, further discouraging its use. The continued reliance on IPv4 infrastructure could lead to issues such as IP address exhaustion and limitations in scalability, making the transition to the more robust and scalable IPv6 protocol increasingly necessary.

Limited IPv6 deployment might also have slowed down technological advancement and innovation in Indonesia, as businesses, educational institutions, and research organizations might have been unable to take full advantage of the benefits offered by IPv6.

Promoting IPv6

The project aimed to tackle these issues by providing IPv6 to end users regardless of their Internet connectivity. By enabling end clients to use IPv6, even if their ISPs did not support it natively, content providers would be encouraged to adopt IPv6. This project could help end users receive IPv6 on their devices with minimal effort and, in turn, drive the overall adoption of IPv6 in Indonesia.

The approach to promoting IPv6 in Indonesia primarily involved campaigns by the Ministry of ICT (Kominfo), IP Forum meetings to encourage telco operators, and workshops provided by the National Internet Registry of the Republic of Indonesia (IDNIC). However, this approach seemed to fall short of comprehending the underlying reasons why numerous organizations were reluctant to implement IPv6, not only in their core networks but also at the edge, reaching clients and end users, as most campaigns only talked about IPv6 itself rather than viewing it from multiple perspectives including social aspects such as organizations’ readiness.

Our approach began with a survey to comprehend the factors that caused organizations to resist change and identify what motivated them to deploy IPv6. Following the analysis of survey results, we offered targeted workshops to participants that encompassed theoretical knowledge and practical implementation in a virtual lab setting. These workshops fostered intense discussions surrounding IPv6 deployment-related technology, such as routing and automation for large enterprises. The aim was to address IPv6 deployment on the border/core router side and at layer three switches, which are prevalent throughout enterprise networks.

Throughout the project, our team prioritized engaging with and addressing the needs of the specific community served, ensuring a tailored and effective approach from project design to implementation. Initially, we sought to understand the factors that caused engineers and organizations to be reluctant to implement IPv6. This understanding was crucial in shaping the project’s design and strategy.

Upon gaining insight into the underlying reasons for resistance to IPv6 adoption, we proceeded with the development and execution of customized workshops. These workshops were designed to cater to the specific concerns and challenges faced by participants, aiming to alleviate their fears and boost their confidence in working with IPv6.

Workshops

The first workshop took place in Balikpapan, Kalimantan. We chose Balikpapan as the location for the event due to its proximity to the proposed new capital of the Republic of Indonesia, Ibu Kota Nusantara (IKN). Our goal was to bridge the knowledge gap between engineers in Kalimantan and Java regarding IPv6. Our initial research showed that engineers outside of Java, including those in Kalimantan, often had a limited understanding of IPv6 and the Internet. To address this problem, we organized a workshop there. The workshop was successfully held and attended by 42 participants from 25 institutions, exceeding our expectations of 30 participants. We had to reject many requests for registration due to the venue’s limited space.

The second workshop took place in Yogyakarta, known as an education city with numerous big universities and over 300,000 higher education students from all over Indonesia. With many higher education institutions in Yogyakarta, IT engineers often exchanged knowledge and experiences in technology deployment, including IPv6.

The workshop in Yogyakarta aimed to ensure that IPv6 was deliverable at scale and targeted engineers who already had a basic understanding of IPv6 but were still reluctant to implement it due to the sheer number of equipment needing reconfiguration. It was attended by 32 participants from 18 institutions across Yogyakarta and the surrounding areas.

The third workshop occurred in Bandung, a city similar to Yogyakarta, hosting top universities in Indonesia. However, unlike Yogyakarta, where IT engineers often exchanged knowledge and experiences, Bandung lacked such an environment. As many universities in Bandung had higher authorities at the national level, we decided to host the workshop there so that the universities in Bandung could help us voice how important IPv6 is. The workshop was attended by 34 participants from 21 institutions coming from West Java.

During the workshops, we encouraged and supported the participants, ensuring they felt empowered and equipped to handle IPv6 implementation in their respective organizations. We motivated participants to embrace IPv6 and overcome existing reluctance by fostering a positive and supportive learning environment.

Throughout the project’s implementation, our team maintained a strong focus on the unique needs and concerns of the target community. We created a highly effective and targeted approach to promote IPv6 adoption among engineers and organizations by addressing these needs and concerns from project design to implementation.

We also shared insights from a previously conducted survey with IDNIC’s trainers, which allowed them to tailor their approach when delivering workshops to the project’s target participants. The survey was distributed to various communities, with a primary focus on universities, as they represented the main target audience for the project. By engaging with these educational institutions, the project team gathered valuable information that helped shape the workshops and ultimately drive the successful promotion and adoption of IPv6 in Indonesia.

Developing a tunnelling broker

Our project also resulted in the development of a tunnelling broker prototype. This prototype was designed to benefit any organization in Indonesia that lacked the necessary resources, such as skilled engineers and reliable ISPs, to obtain their IPv6 blocks.

I will expand on the development of the tunnelling broker in a future post, but briefly, our SDN-based prototype took inspiration from Hurricane Electric’s IPv6 Tunnel Broker and used Mikrotik, the most commonly used network equipment brand in Indonesia, as the foundation of the tunnel broker. Our team created a web-based interface that simplified the deployment process, and we employed the Mikrotik API to configure the platform.

Our testing showed that even residential broadband users who had not yet received IPv6 could now have their own IPv6 block at home. This could be extremely useful for organizations that require IPv6 for experimental purposes before they receive an IPv6 allocation from IDNIC.

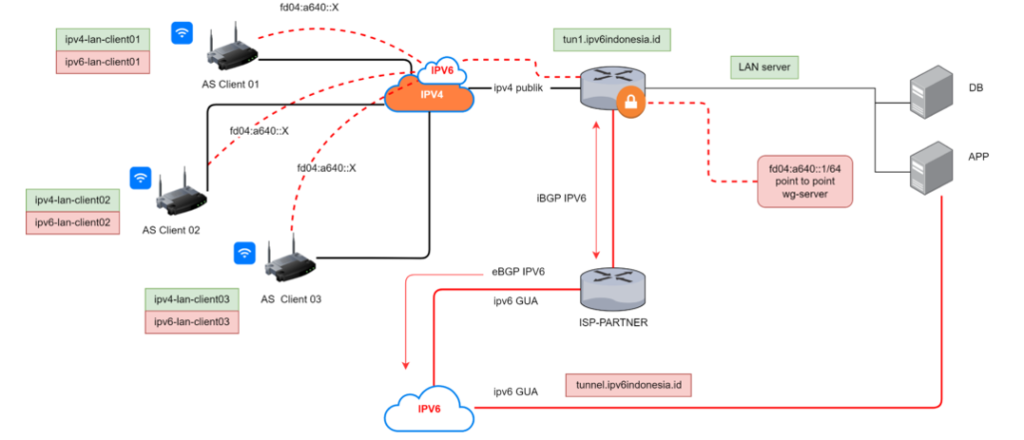

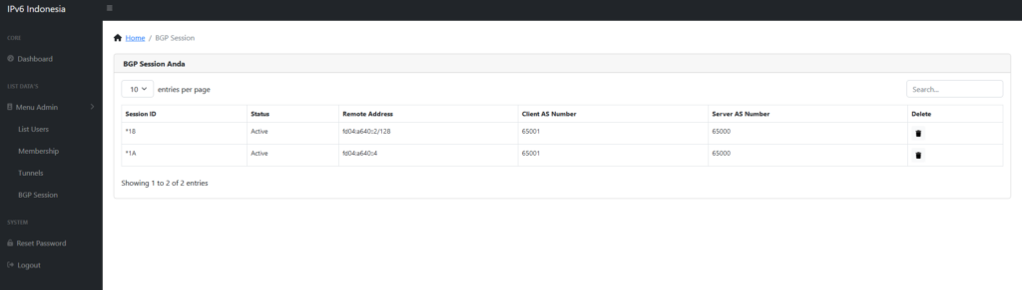

The topology showed how non-IPv6-ready clients could obtain IPv6 from our IPv6 tunnel. Every client had to be registered first on our website, and we recorded some necessary information before releasing the IPv6 block.

Moving forward

Throughout the project, we uncovered critical insights about IPv6 in Indonesia, particularly during the workshops. We learned that implementing IPv6 in Indonesia requires more than technical knowledge; it needs higher-level approval in most organizations. While engineers, who comprised most attendees, could implement IPv6, they often faced resistance from authorities adhering to an ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ mentality.

Another issue is that reconfiguring numerous devices in a large enterprise posed a significant challenge, often overwhelming engineers and making them reluctant to adopt IPv6.

Lastly, Indonesia’s size and knowledge disparity hindered IPv6 adoption. While Java had advanced engineers, other regions lacked a basic understanding of IPv6 and networking. To bridge this gap, we realized the need for increased travel to these areas to provide necessary training and support.

To address concerns regarding IPv6 adoption in Indonesia, we need to engage with higher-level organizations. Significant technological shifts require the approval of executive-level decision-makers, highlighting the need for advocacy at managerial levels.

A significant knowledge gap in IPv6 understanding and network basics outside Java will also need to be addressed with more targeted outreach and education.

Only once these are addressed can we tackle the logistical challenges of reconfiguring large-scale enterprise networks, which currently deter IPv6 adoption across Indonesia.

The journey towards comprehensive IPv6 deployment in Indonesia is far from over, but our project has laid a robust foundation for and highlighted the need for continued progress and expansion.

Dr Mukhammad Andri Setiawan is the Chief Information Officer at Universitas Islam Indonesia, Head of Training and Community development, an IDNIC subunit, and part of the Indonesia Research Education Network (IdREN) committee. He actively engages with IT communities at university networks across Indonesia and the Asia Pacific region. He is also the main contact for Eduroam in Indonesia.

This project was supported by an ISIF Asia grant from the APNIC Foundation. More information is available in its technical report on the Foundation website.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.