The last few decades have not been a story of unqualified success for European technology enterprises. The European industrial giants of the old telephone world, such as the former stalwarts Alcatel, Siemens, Philips, Ericsson and Nokia, have found it extraordinarily difficult to translate their former dominant positions in the telco world into the Internet world.

To be brutally frank, none of the current generation of ‘major players’ in the digital environment are European. Most semiconductor chip fabrication now happens in Taiwan, Korea, the US, China, and Japan. The supply chains for smart devices are even more restricted and they appear to be designed predominantly in the US and manufactured in China. Application and service innovation seems to be dominated by US enterprises.

European innovation — and there have been many important innovations within the Internet environment, such as the web at CERN, or Skype from Estonia — has not directly led to the emergence of European enterprises with global reach. Many of these innovations have turned to US venture capital markets to develop their ideas, resulting in their further development and commercial exploitation in the context of the US business sector in many cases.

Yes, this is a gross simplification of a more complex picture of the global technology landscape. And European enterprises probably contribute as much to the global technology space as the US, China or India. Our collective need for skilled and innovative contributions to the collective effort transcends the capacity of any economy or any single region, and the net contribution from the European sector is as significant as any other. However, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta and Microsoft are all US companies. And the current top ten largest publicly traded companies, as measured by market capitalization, comprises eight US enterprises, and one each from Taiwan and China.

Yes, some of these multinational enterprises may have taken advantage of Ireland as a relative form of corporate tax haven from time to time, but that was about it. The last time European-domiciled enterprises were included in this top ten list was in late 2015, when the Swiss Pharmaceutical corporation, Novartis, and the Swiss food and drink enterprise, Nestlé, were listed in this top 10. The most recent time a European telecommunications and technology sector enterprise was included in this list was more than 20 years ago, when Vodafone and Deutsche Telekom had brief periods of being listed. Whatever is going on here, it looks as if European enterprises are finding it hard to remain domiciled in Europe and keep up with their international competitors, particularly in today’s technology sector.

The concern is that if today’s technology world equates to the previous world of far-flung colonial empires, or that of the world of the industrial revolution, then relative national wealth and prosperity appear to be linked to the ability to master, or preferably dominate, critical aspects of the sector. And in this respect, Europe appears to have been left behind. It still feels to many Europeans as if Europe is over on the exploited side of the techno-colonial landscape, rather than being one of the exploiters. And no doubt that prospect is a particularly concerning one to European Union (EU) political leaders and within the EU bureaucracy.

What should or could the EU do to avoid further decline in this area?

Before looking at the EU response to the questions posed by this situation, there is probably more to this than just keeping up with international competitors and maintaining a visible position in the set of leading enterprises. As tough as this sounds, I’m not sure that this issue of decline in the perceived importance of the role of European digital enterprises in the global technology sector is the full story. It’s also the combination of the increasing level of reliance on the goods and services produced by this sector and the source of these digital goods and services.

The past twenty years has seen the progression of many of society’s activities onto the Internet’s ubiquitous digital platform. These days all forms of retail banking, shopping, and entertainment are largely Internet-based. However, it’s deeper and more pervasive than these simple examples might infer, as we find out from time to time when things break.

From oil pipelines in the US to critical infrastructure systems such as electricity distribution, we all now use various forms of digital cloud command and control structures within the framework of a common Internet. Few services now operate in a manner that is completely independent of the Internet, and perhaps more significantly, most services are critically reliant on the Internet.

This question of reliance can be recast within a more nationalistic tone: To what extent is x economy critically reliant on the continued access to digital services provided by entities who are domiciled in foreign jurisdictions, and even delivered across national borders in a completely seamless fashion?

We can add to this picture of international dependence on the perils of cyber-hostility. How can an economy or regional community defend itself from digital attacks, be it attacks on the provision of the service or access to it by the users? This topic raises a whole set of uncomfortable questions about the level of interdependence within the digital landscape and the vulnerabilities presented by this. To what extent is the resilience of an economy’s digital infrastructure reliant on services provided by foreign entities? And when this interdependence is abused in a hostile context, how can nations respond?

Unlike the national responses to the ongoing COVID–19 pandemic, we can’t simply seal up all movement across the border! At best our current actions are looking to mitigate, to some very small extent, this level of foreign dependence in our digital infrastructure. We saw this thinking exposed in various economies with the construction of 5G mobile infrastructure, where several economies have taken steps to exclude various Chinese enterprises from central roles in these projects. We saw this again in 2018 with the efforts in Russia to construct a Domain Name System (DNS) infrastructure within Russia that could operate only on domestically controlled infrastructure.

As uncomfortable as this interdependence may be, doing something about it in more meaningful ways can be very challenging. For many communities, the issue is simply one of relative size: many economies may have already adopted the position that they are too small to take on today’s digital behemoths and declare independence and self-sufficiency (in the sense of eliminating their dependence on them).

Domestic data retention measures seem like a relatively poor second choice substitute to address such fundamental concerns. No matter how uncomfortable it may be to observe that individual economies are now critically dependent on these digital giants, they also have been forced to acknowledge that it is just not feasible to contemplate alternatives that have domestic ownership and control. Other economies are not so willing to embrace a future that includes such critical dependencies on services provided by foreign enterprises at a fundamental level. I would suppose that they feel they are large enough to take on these enterprises and use their resources to decrease this level of foreign dependence for critical services. And it is in this situation that the EU community finds itself today.

I should hasten to add at this point that this situation is not the outcome of any chosen strategy on the part of today’s digital giants. In designing an Internet architecture that was based on stateless packet forwarding and eschewing the traditional control points of network state as was used in the circuit-switched telephone network, we not only got a new system that could scale its infrastructure and services to the size of today’s Internet; we also built a network and a service platform that paid no heed to concepts such as national or regional political boundaries, network control points, bilateral infrastructure and traffic agreements. Transaction-based accounting practices and various forms of international financial and regulatory agreements were inevitable.

The Internet was not constructed as an amalgam of various national networks but was conceived and constructed as a single artefact that had never integrated such geopolitical concepts into its internal architecture. The result was somewhat inevitable in that a large enterprise in this environment could reach across the entire span of the network without any technical requirement to negotiate national boundaries.

In retrospect, where we find ourselves today, as discomforting as it is to many, is a natural consequence of the technology choices made in the basic architecture of the packet-switched Internet.

We can take this macro view of regional interests and the modes of participation in the technology of the digital environment and apply it at a finer level of granularity to individual activities within this sector. What I want to examine is the very particular issue of the DNS, the market for name resolution, and the European perspective.

The DNS really is everything!

The Internet’s name system is an important topic of conversation in today’s Internet, as it appears that the DNS is the last part of the ‘glue’ that holds the Internet together and is the defining medium of what is ‘the Internet’.

IP addresses, the other part of the Internet’s original common infrastructure, appear to have become a more amorphous concept. We’ve passed all the heavy lifting of service identification and rendezvous over to the name system, and passed the issue of endpoint identification over to the applications and service environment.

This central role of the DNS is reflected in the way we use the DNS and related services:

- Content filtering is a role executed by filtering in DNS resolvers. If the DNS does not resolve a name, then that name and the associated service simply does not exist.

- Service rendezvous is a role that is increasingly being undertaken by the DNS, such as in the service binding (SVCB) and HTTPS resource records. Instead of asking the DNS for the IP address associated with a DNS name we can now ask the DNS to inform the client of where to connect, what port to use, what encryption protocol is needed and even details of the public key information to support this encrypted channel.

- Our privacy concerns are reflected in our efforts to improve the privacy and trustworthiness of DNS resolution transactions.

Because of the role of the DNS as an essential facilitator in every network transaction, the DNS really is the most critical component of the Internet’s infrastructure these days.

The DNS resolver landscape

In the early days of the Internet when mainframe computers were the only thing around, the name system was a far more rudimentary service.

Every host had a local copy of a simple text file, ‘hosts.txt’, and applications that wanted to translate a name to an IP address to use on packets consulted this file for a match. If you look hard on the platform you are using to read this, you will still find a remnant of this host file. The task at the time was to coordinate all these independent versions of this file so that the same name was recorded with the same address on all the Internet’s hosts.

As the Internet grew this task became harder. The first step was to augment this local hosts file with a lookup into a shared distributed database. If the name was not defined in the local hosts.txt file, then the platform would pass a query to the local implementation of a DNS server, which would then perform a directed query through the distributed database. The problem is that this database query could be extremely slow.

The design response to increase the efficiency of the DNS was to use local caches. The name-to-address binding changed infrequently, so once a local implementation is cleared of a binding of name to address, it could store this and reuse it for subsequent queries. When the caches ran ‘hot’, the performance of this database query was as quick as a local host’s file, but with far better consistency of the overall resolution of names.

We distinguished between the DNS servers that handled queries in end hosts (stub resolvers) that worked at the edge of the network and those that assisted a collection of stub resolvers by acting as their agent and performing their queries for them (recursive resolvers). This not only offloaded a set of database navigation functions from the stub resolver to the recursive resolver, it also allowed these recursive resolver middle-agents to cache the answers for the complete collection of stub resolver clients, further increasing the effectiveness of caching in the DNS.

For many decades these resolvers were integrated into the Internet’s service landscape by assigning the role of operating the recursive resolvers to the local Internet Service Provider (ISP). The ISP not only provided its clients with access to the Internet but also provided access to the common name system through the provision of these recursive resolvers for its clients.

This was a relatively stable arrangement for many years, but at the same time, there was a lot of churn lurking just below the seemingly placid surface of the DNS. It became increasingly apparent that operators of these recursive resolvers were privy to large volumes of ‘useful’ and timely information about user behaviour. It was also apparent that operators of these resolvers were in a unique position to control the visible content that was accessible for their users.

This was an enticing temptation for some ISPs. In this era of the Internet’s surveillance-based economics, a real-time stream of data about what users are doing has considerable market value, and the DNS resolvers’ query logs had considerable value, despite the somewhat disturbing privacy issues.

Given that the ISP was unable to convert the costs of operating its recursive resolver service into a revenue stream by charging its users — and the ISP business has been squeezing its margins for many years — any additional revenue stream must be an interesting proposition. There is also the possibility of monetizing the DNS service by performing NXDOMAIN substitution. Here, instead of responding that the name does not exist, the ISP can instead respond with a sponsored referral to a search engine.

It’s not just ISPs who are exposed to the temptation to play in the DNS. The DNS has become fodder for various national regimes to both observe their citizens and impose controls on their online activities. These days it is common for governments to proscribe the resolution of certain DNS names, and phrase this as a legal obligation for ISPs and other domestic service providers. The motives for these blocklists are varied and include attempting to curtail the propagation of malware, disrupt the command-and-control channels of coopted zombie attack bot armies, censor offensive content, and protect rights holders from efforts to infringe their intellectual property rights.

This latter aspect of DNS censorship and the EU is already an active topic.

Interest in intellectual property rights associated with Sony Music Germany bought a suit against the DNS open resolver provider Quad9 in a German court. The court ruled that Quad9 must block the resolution of a domain name of a website in Ukraine that itself does not hold copyright-infringing material, but instead contains pointers to another website that is reported to hold alleged copyright infringements.

Quad9’s interpretation of this ruling is that queries received from IP addresses that can be geolocated to Germany must generate a SERVFAIL response from Quad9’s recursive resolvers.

There are several curious aspects of this situation. It appears that the other significant DNS open resolver providers (Google, Cloudflare, and Cisco’s OpenDNS) have not been similarly targeted by legal action in Germany by Sony. Perhaps the Swiss domicile of Quad9 made it a more appealing target for German legal action. Or perhaps there are some involved issues in attempting to compel a non-EU provider to take certain actions to block content.

Open DNS providers do not conventionally sell their services. There are no paying clients. No contracts. Nothing. Clients of these services make their own decision to use these open DNS services and do so without any form of payment or any formal commitment. Possibly in terms of enforcement mechanisms, this becomes an issue for the individual clients of this service and not necessarily an issue for the non-EU DNS resolver service operators.

These developments in coopting the DNS for such purposes has not gone unnoticed. Some clients, both consumer and enterprise clients, may feel that the DNS filtering being performed is unwarranted. Clients may be uncomfortable with their ISP performing such surveillance.

One potential answer for such clients is to operate a recursive resolver within the client network. That measure can circumvent any DNS filtering that is being performed by the ISP’s recursive resolver. The measure also stops providing a direct feed of client activities to the ISP’s recursive resolver. However, that is also an additional role that the client has to perform.

The rise of open resolvers

The Open Resolver model is an alternative here. The idea is that the open resolver may not be operating in the same regulatory or legal framework as the client and the client’s ISP and may be able to resolve DNS names that would otherwise be proscribed. The Open Resolver may be in a different legal regime and may not necessarily be subject to domestic law enforcement processes of discovery of DNS queries.

In December 2009, Google entered this space with its public resolver offering — 8.8.8.8. Google’s reasons for entering this market were couched in terms of better performance and better security in the handling of queries. However, it also should be observed that Google had a strong commercial motive to enter this space — their major commercial asset is their search engine.

If the DNS lookup could be transformed into a search engine, then this would represent a direct threat to their business, and in performing NXDOMAIN substitution, this was exactly what some ISPs were doing. If the ISPs were performing this pseudo-search in the DNS as a revenue-raising activity, then Google’s DNS resolver represented an alternative that did not attempt to raise revenue from the ISP-operated DNS but eliminated the need for the ISP to operate any general DNS resolver infrastructure for its clients. All it needed to do was to forward all client queries to Google’s service.

From Google’s perspective, I would guess that this open resolver project represented a relatively small outlay to further protect its core business asset.

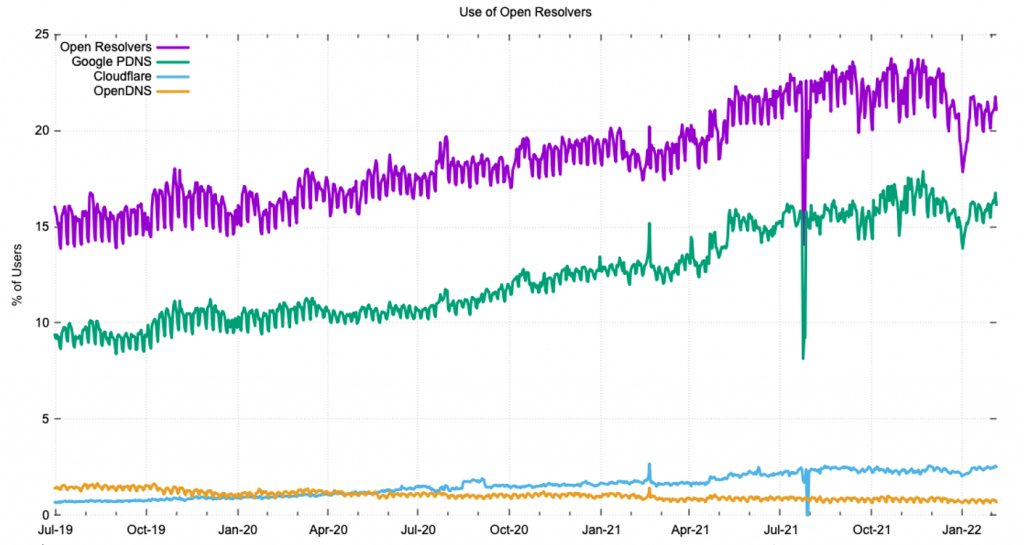

Open resolvers represent a major shift in the DNS landscape, and Google plays a major role these days. Figure 1 shows the ‘market share’ of the three largest DNS open resolvers, as a day-by-day time series since July 2019.

Some 20% of the Internet’s user population use an open resolver to resolve names, which is an unexpectedly high number. Of these open resolvers, Google has the major share with its public resolver offering. These days one in six (16%) of the world’s users use Google’s service. Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 service is used by 2.5% of the world’s users and OpenDNS has a 1% market share.

It is also worth noting that the open resolver metrics have a visible weekday/weekend variance. The use of open resolvers is higher on weekdays, pointing to a likely preference for enterprise customers to eschew the ISP’s DNS offering and prefer to use an open resolver service instead.

Now let’s turn our attention to the EU and see if the same situation holds there.

Resolver landscape in the EU

Just how significant is this movement to use DNS open resolvers in EU member states? Table 1 compares the data on the use of public DNS resolvers in January 2022 between the Internet-wide totals and the total in the EU.

| January 2022 | All | EU |

|---|---|---|

| Samples | 455,721,405 | 41,635,975 |

| Same AS (ISP) | 67.38% | 76.96% |

| Total Open Resolvers | 20.44% | 15.84% |

| Google 8.8.8.8 | 15.56% | 12.65% |

| Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 | 2.35% | 2.89% |

| OpenDNS | 0.74% | 0.65% |

| Quad9 9.9.9.9 | 0.14% | 0.06% |

Table 1 — Use of open resolvers in the EU, January 2022.

The use of DNS open resolvers in the EU is slightly less than the Internet-wide average. Google’s service is 3% less common, and Cloudflare’s service is slightly more (0.5%) common in the EU.

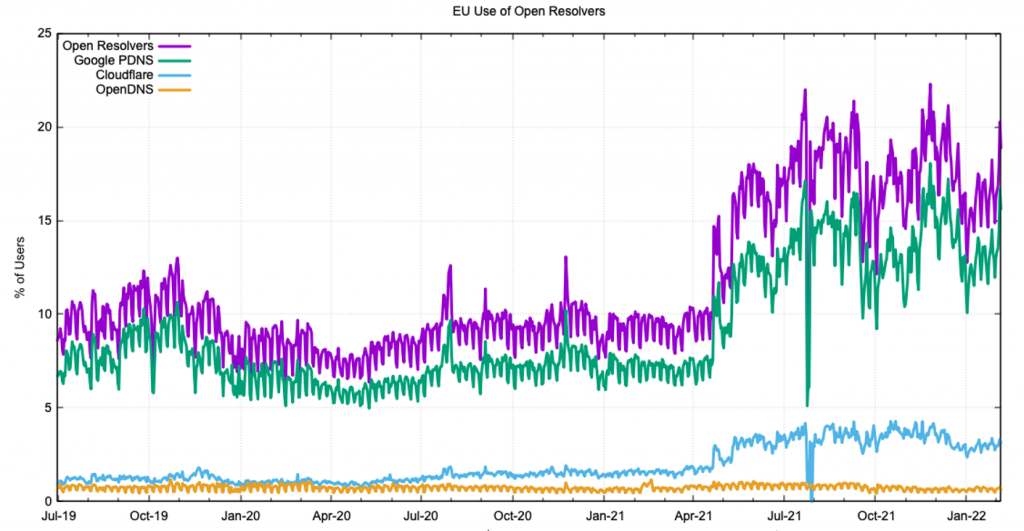

Figure 1 also shows steady growth in the proportion of users who have their queries passed to DNS open resolvers over the past 30 months. What is the trend data for the EU?

As shown in Figure 2 the use of open resolvers has been growing over the past 30 months (the discontinuity in August 2021 is an artefact of the measurement system). The use level has almost doubled in this period, which is a higher relative growth rate than the overall Internet-wide numbers.

We’ve been looking at the EU as a uniform collection of economies. To what extent do they differ between economies?

| CC | Name | Samples | Same AS | All Open Resolvers | Cloudflare | OpenDNS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | Austria | 950,035 | 74.0 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| BE | Belgium | 1,192,973 | 94.6 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| BG | Bulgaria | 549,103 | 67.3 | 16.2 | 13.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| CY | Cyprus | 121,955 | 52.6 | 35.8 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 24.6 |

| CZ | Czechia | 1,000,906 | 80.1 | 15.9 | 12.8 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| DE | Germany | 8,112,657 | 72.6 | 26.0 | 20.8 | 5.4 | 0.5 |

| DK | Denmark | 648,425 | 77.1 | 16.1 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| EE | Estonia | 135,535 | 94.0 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| ES | Spain | 4,820,556 | 79.3 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 1.9 | 0.0 |

| FI | Finland | 559,249 | 88.8 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| FR | France | 6,310,803 | 69.5 | 21.0 | 16.0 | 4.7 | 0.4 |

| GR | Greece | 860,678 | 86.1 | 6.5 | 4.9 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| HR | Croatia | 295,220 | 73.6 | 7.4 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| HU | Hungary | 860,014 | 89.7 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| IE | Ireland | 481,699 | 79.7 | 17.2 | 14.9 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| IT | Italy | 4,370,226 | 90.7 | 7.9 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| LT | Lithuania | 257,982 | 89.1 | 9.0 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| LU | Luxembourg | 70,770 | 58.4 | 40.9 | 29.7 | 2.8 | 8.6 |

| LV | Latvia | 180,075 | 84.3 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| MT | Malta | 42,435 | 34.0 | 33.9 | 9.8 | 0.9 | 23.1 |

| NL | Netherlands | 1,877,122 | 50.4 | 26.0 | 22.2 | 3.9 | 0.6 |

| PL | Poland | 3,547,175 | 72.2 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| PT | Portugal | 916,876 | 88.2 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| RO | Romania | 1,548,032 | 89.8 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| SE | Sweden | 1,194,018 | 75.1 | 8.5 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| SI | Slovenia | 199,861 | 94.0 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| SK | Slovakia | 528,112 | 82.9 | 14.1 | 9.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| EU | EU Total | 41,632,502 | 76.9 | 15.8 | 12.6 | 2.9 | 0.6 |

| XA | World | 455,721,600 | 67.4 | 20.4 | 15.6 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

Table 2 — Use of open resolvers in EU member states, January 2022.

There is a strong preference to use the ISP’s provided DNS resolver in Belgium, Estonia, Italy, and Slovenia, where more than 90% of the samples show that the local resolver is being used. Google is used in more than 20% of cases in Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Cloudflare is used by more than 4% of users in Germany, Denmark, and France. OpenDNS is used extensively in Cyprus and Malta.

Is the observation that some 16% of users in the EU use DNS open resolvers a significant issue for the EU, or is it a number that warrants no particular concern? Yes, it’s a big number, and it is getting bigger. On the other hand, it’s a smaller proportion than the world average.

It also should be noted that Google has been clear in maintaining that their resolver service is a precise and accurate representation of the DNS. Nothing is omitted, added, or altered in responses from their recursive resolver. Google does not disclose data about the way its resolver is used other than what is required under various jurisdictions. Google report some information on the requests for data in a transparency report.

The reporting for the ‘Same AS’ resolver could be misleading to some extent. Even within the ISP industry, the DNS function has been the subject of outsourcing, and Nominum became a major player in this service market. In 2017, Nominum was sold to Akamai. So today, Akamai is now a significant service provider to ISPs for DNS resolution. What this means is that the true extent to which the DNS has been outsourced to a small number of service providers, and the pace at which the DNS as a market is consolidating, is not readily apparent to any outside observer.

DNS4EU

DNS4EU is the name of an EU initiative intended to exert more control over the DNS within Europe, aimed specifically at the current level of use of open resolvers in the EU. As Andrew Campling reported in January 2022:

“The European Commission announced its intention to support the development of a new European DNS resolver (“DNS4EU”) in December 2020. It has been in dialogue since then to refine its thinking, in particular placing much greater emphasis on the potential cybersecurity benefits that could arise from the deployment of the resolver.”

Andrew Campling

This program aims to address the consolidation of DNS resolution in the hands of a few companies, which renders the resolution process itself vulnerable in case of significant events affecting one major provider — at least that’s the rationale provided in the EU documents. It appears that DNS4EU will provide EU funding to support part of the capital costs for EU enterprises to construct DNS resolver services in the EU.

The intended benefit is to provide a DNS resolution service that can comply with the various content regulations in the EU by blocking the resolution of certain DNS names. It is unclear in my reading of the proposals how the DNS query data is to be handled, and whether such financially supported DNS resolver services would be obligated to share the DNS query data with various EU law enforcement authorities and security agencies. However, the reference to potential cybersecurity benefits suggest that some form of data sharing is being contemplated.

Related DNS4EU material suggests an expectation of a ‘better’ DNS resolver service, although many of the benchmarks of what constitutes a ‘best practice’ DNS resolver seem to be based on measurements of Cloudflare’s and Google’s resolver services.

Presumably, then, the interpretation of ‘better’ relates to the level of service provided by ISP-operated DNS services. However, the implication that EU money would be used to provide competition in the DNS resolution service market by somehow highly directing funding to existing ISP-operated DNS resolvers seems to redefine the role of public funding in potentially anomalous ways.

Perhaps the EU folk have been looking at CIRA’s Canadian Shield DNS resolver where the .ca registry has launched a DNS open resolver service. The service appears to be fully funded by CIRA, and, like Quad9’s service, appears to use active DNS filters that are informed by malware and threat feeds and conform to Canadian policies. It’s useful to note that CIRA is not a government body, but, like many other ccTLD registries is a private, not-for-profit, member-based organization.

There is another interesting example with the .cz registry, CZ.NIC, who have funded the development of the KNOT resolver (and server). One of the earlier concerns with the DNS infrastructure was the lack of diversity of implementations of the protocol standards. Most resolvers and servers ran the BIND software. There was a deliberate effort to increase the diversity of DNS implementations, and these days three of the major DNS implementations — NLNet’s Unbound, CZ.NIC’s KNOT and PowerDNS — are all outcomes of European projects. Much of the DNS infrastructure runs on these implementations today.

In some ways, the DNS4EU program is not all that different from these efforts, particularly the CIRA initiative. If you are unhappy with the collection of open resolver services and believe that you can do a better job, then perhaps the best option is to transform this sense of unease and discomfort into action and run your own.

But if the party wanting to prove that it can do a better job is the public sector itself, then this raises some predictable issues relating to public sector involvement in private sector activities. One of these issues is the need to tread carefully, to not scare away all private capital. Why would a private enterprise continue to invest in a service sector when it is competing with the public sector? How can a fair set of rules be enforced in the market when the rule-setting body is an active player as well?

What about ISPs? Why should they continue to spend their own money running a DNS resolution service for their clients when the EU is channelling funds to some third party to run an open DNS service? Why not just use a simple forwarder and pass all the ISP queries onto this same service? Is the level of funding from the EU to run this service truly at a level where the successful bidder is in a position to build and operate a DNS resolution infrastructure that can cope with the demands posed by some 500 million users?

Now it could be argued that this is what Google is doing already, so there is proof that this is not an infeasible ask. But Google is indeed special.

Google is spending money and resources in defending its core business asset of search. And in running an open resolver that faithfully presents the contents of the DNS to its users, it is helping to prevent the perversion of the DNS into a search engine.

The issue here is that this is a relatively unique motivation. Other DNS resolver operators do not share that motivation, given they are not major players in the search space and have no existing business asset they are attempting to defend. If a DNS resolver operator’s operating resources are fixed, then the onset of larger query volumes results in a degraded service, which tends to defeat the purpose of operating this service in the first place.

It is challenging to see how the DNS4EU program of part-funding of the capital costs of setting up a DNS open resolution service and no operational funding would create a sustainable business model in the DNS resolution market.

The harsh truth here is that DNS resolution is a market failure, in that users don’t pay to have their queries answered and information publishers don’t pay to have their answers served. The reason why ISPs run DNS resolvers is that this is what ISPs have always done. But DNS resolution is a cost centre for ISPs and there is no clear business motive to increase their investment in DNS infrastructure beyond the level of functional adequacy given that few, if any, users make their ISP selection based on the quality of the ISP’s DNS services.

So, on the one hand, it’s easy to understand the situation the EU finds itself in, where significant parts of its internal digital infrastructure are being operated by foreign-owned and controlled enterprises, is not acceptable. And equally, it’s entirely understandable that the EU would wish to change this picture of dependence.

But having largely deregulated this industry and having dismantled many of the restrictions on international investment in digital services, the set of tools that are left to governments are, at times, somewhat inadequate when they contemplate forms of active intervention in the marketplace to redress what they perceive as strategic imbalance and vulnerability. The results of their various rule-setting efforts can, at best, be judged as a mixed outcome that has had some positive and negative outcomes. And, at worst, it can be judged as no more than placing a further brick in the wall of industry consolidation into the hands of the existing digital behemoths through imposing more overwhelming impediments in the path of emerging competitors.

So, what can the EU do?

It seems that DNS4EU is an example of the line of thinking that if you can’t throw rules at a problem then try throwing money at it!

I’m not optimistic this approach will do any better than the previous rule-setting efforts. Creating a new set of enterprises based on dependence on government financial subsidies does not necessarily create a new set of competitors. The more likely outcome is that it merely creates a new set of dependants on the public purse!

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.