This article is the fourth in our THSeries ahead of APNIC 48 in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

The first resemblance of the Internet in Thailand was a UUCP gateway linking UNIX systems in Australia, France, Japan and USA. It was established in the late ‘80s by a group of local and budding computer scientists at the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) as a means to connect with their home and partner institutes. One of those scientists was Thailand’s ‘Mother of the Internet’, Kanchana Kanchanasut.

“We all had experience with email at our home or host universities; it had become ‘the’ way that academics communicated. When I returned to Thailand after several years in Australia studying and working, I had to resort to writing letters to my colleagues and research partners, which, as you can imagine, took so long to get a reply from. If I and my colleagues wanted to stay in Thailand and do our research, we needed email; and no one was going to do it for us except ourselves,” says Kanchana.

“If you weren’t on email, nobody would talk to you. So, we decided to do something about it.”

Establishing the Internet in Thailand

Kanchana and her colleagues at AIT set up a Unix-based workstation that they used as a server using UUCP. With the introduction of the ACSNET’s SUNIII software by the Australian International Development Project in 1988, the team was compelled to register the .th domain name with ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) — the precursor of today’s Internet — paving the way for members of the academic community in Thailand to access email on the Internet.

Registering .th was merely a task in Kanchana and her team’s objective to gain email. However, as email, and the Internet, became more popular by the late 90s, and with it, discussion of who regulates and ‘owns’ it, she realized the responsibility was one that needed to be discussed.

“We asked the community who should run the domain name, whether it should be the government, private industry or the universities. Eventually we decided that an independent foundation would be the most neutral and sustainable option,” says Kanchana.

Taking cues from the recently established ICANN, the THNIC Foundation was eventually formed.

As an international university, the significance of this was not lost on its staff and students. However, Kanchana remembers that it took some time until other universities in Thailand realized the benefits of email messaging and file sharing; through no fault than Thailand being a developing economy.

“Most local universities at the time were using personal computer machines running Microsoft DOS because that’s the only thing they could afford. Then the Australian International Development Project helped one university in the south of Thailand to acquire a UNIX machine and connect all universities in Thailand with the UNIX systems together,” says Kanchana.

This was the start of the first Thai network, connecting Prince of Songkhla University, Chulalongkorn University, Thammasart University (Rangsit) and AIT. By mid-1992, the first PING from Thailand to UUNET in the US went from Chulalongkorn University.

An important effect from the growing network was the emerging academic Internet community which Kanchana credits for making the decision to implement TCP/IP and also nurture the formation of commercial Internet access in Thailand in 1994.

Helping develop my society for public good

Having gained access to email and the Internet — and in the process effectively introducing it to Thailand — Kanchana could have been excused for returning to her life of research and leaving others to manage and grow the fledgling Thai Internet. However, the entire process appealed to her sense of not being able to walk away from a job until it was done.

It would have been hard to foresee the extent of the job as it turned out.

“I’m no angel! I didn’t plan to do this kind of thing. I always thought that some other people would do this, and some would do that, but that didn’t happen. That’s why I’ve been on this journey for over 30 years,” says Kanchana.

“I say journey as I never plan anything. I kind of find a problem and then try to work with others to solve it. You have to keep in mind what your main principle is. For me, I just want to help develop my society for public good. That’s what I stand for.”

This ‘can do’, selfless attitude comes naturally to Kanchana and has served her and those associated with her projects through the Internet Education and Research Laboratory (intERLab) at AIT — which she set up to provide much needed capacity building for Internet engineers in the region in addition to producing a steady stream of graduates in computer science and engineering — well. It has also been a cornerstone of her involvement in establishing multiple social enterprises, Thailand’s first neutral Internet Exchange, as well as her research into disaster recovery and community networks that she’s invested most of the last 15 years in.

Nurturing community networks to help Thailand and the world

“My interest in community networks was born out of the 2004 tsunami that hit the south of Thailand. I had been interested in the application of mobile and ad hoc wireless networks and this tragedy provided the perfect case study, in particular, how such technology can be quickly and relatively easily deployed when disaster strikes,” explains Kanchana.

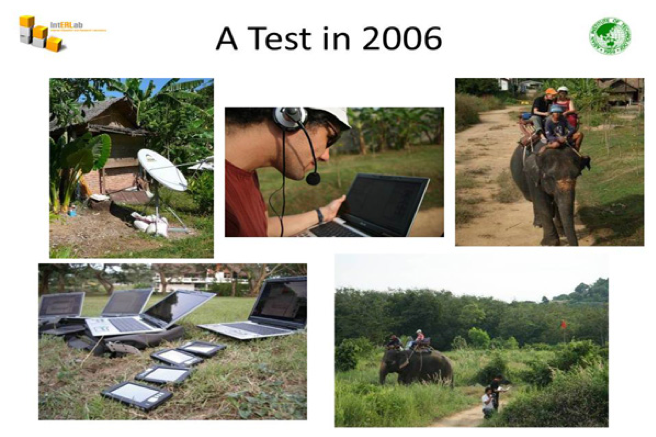

Two years later, in collaboration with the Hypercom Project of the Institut national de recherche en informatique et en automatique or INRIA, France, Kanchana was involved in Project DUMBO (Digital Ubiquitous Mobile Broadband OLSR), which experimented with using Mobile Ad Hoc Networks (MANETs) to allow rescue teams to communicate in simulated post-disaster situations where fixed network infrastructure was unavailable.

DUMBO allowed video, VoIP and short messages to be simultaneously transmitted using ordinary devices (laptops or PDAs) as wireless nodes. During the simulations, the project experimented with using several modes of vehicle-to-vehicle networks including long-tailed boats, Tuk-Tuks, and the project’s namesake, elephants.

Figure 1 — The DUMBO I experiment was successfully carried out involving two simulated disaster sites in a forest environment with elephants carrying supplies and communication nodes linked among the two sites and a simulated headquarters in Bangkok using IPStar VSAT satellite. (AIT)

Kanchana says that the most rewarding part of the project was seeing the methodology being deployed and assisting in real-life disaster situations, including in Myanmar, following tropic cyclone Nargis in 2008 and Nepal, following the 2015 earthquake.

“Following news of the earthquake, our AIT Nepalese students volunteered to configure our mobile routers, which we were able to ship to rescue camps and a few hospitals. The medical staff in those hospitals were using our system in place of telephones, which were either congested or down in some places for weeks,” she says.

intERLab also received an ISIF Asia grant in 2009 in support of the DUMBO project.

Read: Restoring the Internet in Nepal, one year after the quake

The project also inspired Kanchana and her intERLab team to look at how wireless technology could be used as an inexpensive, feasible, and self-sustainable means for rural communities in Thailand to connect to the Internet. The resulting TakNet projects and Net2home start-up have connected more than 200 households across 17 communities and, in the process, upskilled locals to look after the networks.

Read: TakNet – Community networking in Thailand

Net2home serves as a cross between a wireless Internet Service Provider and a community network operator, where the infrastructure and connectivity are provided by the social enterprise while the network itself serves as a community mesh network, with users agreeing to be part of the network and paying for the incurred electricity costs as well as the monthly fees.

“Capacity development is probably the most important component of community networks,” says Kanchana. “By training people in the community to sustain and take ownership of the network there’s more chance that it will be used when we leave.”

Whether connecting the unconnected turns out to be another case of how email enabled her and her colleagues 30 years ago is anyone’s guess. But you can’t help think it has the potential of unearthing another pioneer.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

Today

Thailand internet (Sep 2019)

200M/200M only 590Baht (18USD/Month)

1,000M/200M only 890Baht (27USD/Month)