Mobile Internet usage has exploded over the last decade and the number of mobile web users is expected to reach 5.9 billion by 2025. Smartphones are increasingly common and, for the last three years, mobile devices have surpassed desktop as the primary device to browse the web. Despite the clear shift toward mobile browsing, much of the web has been designed for desktop machines on a wired connection.

This ‘disconnect’ typically translates into complex websites that offer poor quality of experience to mobile users, something that has recently received a significant amount of attention from researchers and industry alike. From industry, projects such as Facebook Instant Articles rely on formats and infrastructure to speed up browsing, while Amazon Silk and Opera Mini do it through specialized web browsers.

Accelerated Mobile Project (AMP) is a recent effort started by Google with a similar goal of improving the mobile browsing experience, providing content creators with what is essentially a stripped-down and optimized version of standard web development tools. Some anecdotal evidence suggests that AMP can indeed improve users’ web browsing experience.

What is AMP?

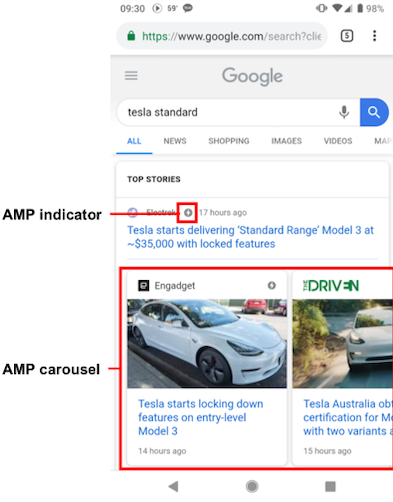

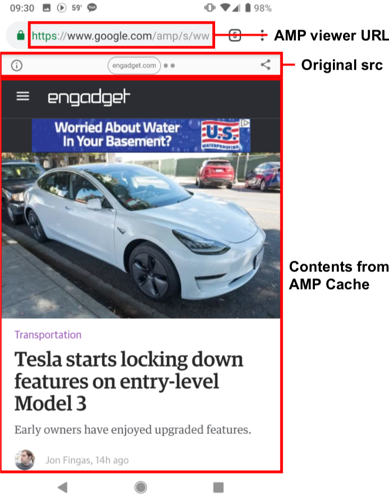

First announced in 2016, Google’s AMP is a web component framework aimed to improve mobile web performance by reducing website complexity and leveraging Google’s massive infrastructure and presence throughout the web browsing pipeline. When a user performs a search through an AMP-enabled browser, the search results will likely include AMP-enabled pages, marked with a small lightning sign. When the user clicks on any of these AMP links, an AMP page will be rapidly rendered.

The fast page loading comes mainly from three sources: simpler pages, caching in the AMP CDN and pre-rendering of page search results.

First, AMP largely simplifies the original webpage and replaces some of the standard HTML tags by its own in a performant manner. Also, AMP restricts the use of author-written JavaScript and the inclusion of CSS files in order to minimize file size and improve load time. The AMP team, in particular, put effort into preventing JavaScript and CSS from blocking the DOM rendering during the initial page load, and making objects load lazily.

Second, AMP leverages Google’s AMP CDN for caching.

Lastly, some AMP pages in the search results that users may potentially click (for example, top result) are pre-rendered in an effort to further reduce loading times. This particular technique results in instant-like access to the target page.

So, is it actually faster?

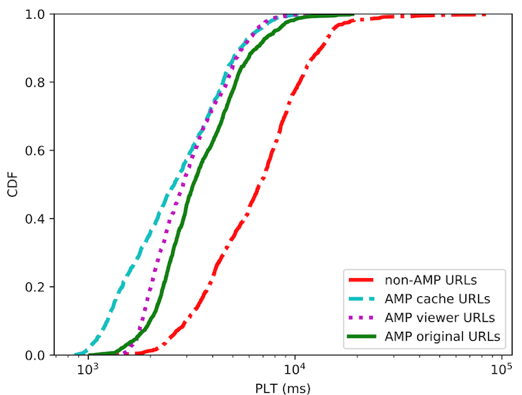

One of the commonly used proxies for quality of experience (QoE) is Page Load Time (PLT), the time until all objects on a page have been loaded. To characterize the impact of AMP on mobile web QoE, we at Northwestern University, in collaboration with IIJ, compared the PLT of four different versions for over 2,000 pages we found using trending keywords in Google.

The different versions help, to some extent, isolate the contributions of the different features of AMP.

- The non-AMP version is just that, a regular HTML version of an AMP page which can be commonly found in a ‘link’ field of an AMP page header.

- The AMP original page is the AMP page served by the content provider or its CDN.

- Typically the AMP original page is not served directly to users but it’s first validated and cached on Google’s own dedicated CDN as the AMP cache version.

- The AMP viewer version is the rendered version of the AMP cache page, potentially pre-rendered even before the user clicks on it.

Figure 3 shows the PLT (average of three) of these versions.

Figure 3 — The Cumulative distribution function (CDF) of page load time (PLT) of different AMP versions.

The graph shows that for most pages, any version of AMP has better (lower) PLT than their non-AMP counterpart, with the average PLT dropping from 7.7 secs to 3.06 secs, a 2.5x improvement.

As expected, AMP cache has the best performance since it is the most optimized version, and the performance gaps between AMP pages are significantly smaller than the differences between AMP and non-AMP pages.

AMP viewer versions are worse than their cached version in this graph since this plot does not capture the impact of pre-rendering.

Where is the performance improvement coming from?

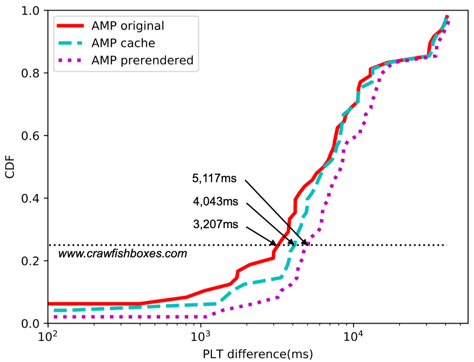

The largest performance benefits comes from a drastic reduction in the number of various objects loaded in AMP. AMP pages include, for instance, half as many HTML and one-fourth as many images, on average, than their non-AMP counterparts. Besides the time saved fetching and rendering those additional objects, fewer objects also mean fewer DNS requests.

The following graph clearly shows this, plotting the performance improvement of each AMP version, over the corresponding non-AMP version. A horizontal line across this graph shows, for a particular webpage (www.crawfishboxes.com), the PLT improvements over the non-AMP version of the AMP original, AMP cache and AMP pre-rendered versions. The largest ‘jump’ comes from the use of AMP, as illustrated by the AMP original curve.

Figure 4 — The Cumulative distribution function (CDF) of page load time (PLT) of AMP versions from its non-AMP counterpart.

AMP cache provides a less impressive benefit, by comparison. A more significant jump is given by pre-rendering which, in this case, results in a 1.9 sec improvement on PLT, on average. Pre-rendering is indeed essential for the seemingly ‘instantaneous’ page load user experience with AMP.

Of course, there is no such thing as a free lunch; prefetching and pre-rendering come with a hidden cost. On average, a pre-rendered page in the background of a Google search result page spends 1.4MB extra data even when/if a user decides not to load the pre-rendered page.

To AMP or not to AMP?

We found that AMP can indeed reduce the complexity of web pages and this reduction does result in significant performance improvement on mobile users’ QoE. Despite the controversy surrounding AMP and its impact on the health of the Web, as Google continues to push AMP and users recognize its advantages, we anticipate that a growing portion of the mobile web will opt for AMP-like technologies.

Our work contributes an independent analysis of AMP’s performance benefit which, we acknowledge, is just one of the many factors determining mobile users’ web experience.

For further information on this research work, read our paper, AMP up your mobile web experience: Characterizing the impact of Google’s Accelerated Mobile Project to be presented at ACM Mobicom this November.

Byungjin Jun is a PhD Student at Northwestern University.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.

For http://www.crawfishboxes.com, do you have PLT results for the non-AMP version?