At the IETF 98 Plenary, Niels ten Oever and Dave Clark presented on human rights and the Internet. Niels is one of the primary authors of the lead draft in the IETF Human Rights WG.

Niels began his presentation with an analysis – with a strong theoretical computer science point of view – of what human rights are, taking us on a historical tour of the founding documents including the Magna Carta in 1215, the Bill of Rights in 1689, the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776, and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789.

In 1947, Niels pointed out, we got something different: not just a definition of government/personal rights defined as a function of the state, but a document which defined human rights as a thing in themselves, which became incorporated into a formal document structure, the International Bill of Rights.

As part of his analysis, Niels explored the interaction of rights and technology. The 2012 UN declaration attempted to define the rights as being the same online and offline. But, it’s clear this hasn’t made it magically come true. We’ve already had 2015 and 2016 reviews to try and understand where the gaps are. In 2017, we have a stronger sense that pervasive surveillance and related activities have significantly eroded our rights in the modern world, especially online.

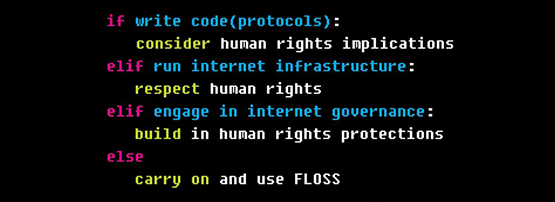

The IETF has been trying to address this from a technical standards perspective with a documentation process to review the implications of human rights on protocols and standards in our area. An affirmation that the work we do here is not “value neutral” was made in RFC3935 for instance.

Niels also reminded us that we we’re not the only people in the room working on this, with the IEEE and ISO both having published statements on the implications of human rights on protocols and communications.

Dave Clark segued from this, with a nice discussion about what differences there are from online and offline behaviour regarding the human rights questions.

Dave has been writing about the issues of policy tensions in Internet Governance since 2005. He characterized this tension as a “tussle” between people’s preferences in the network.

Dave wanted us to understand that this process is taking place “inside our own process” – this isn’t something imposed from above after the event, it’s something happening inside the protocols, specifically inside the protocol design process. Dave reminded us of the “values in design” movement active in Computer Science circles. And, that the design process demands us to think not about how to play the game – or even to try and play – but to think about how we can “tilt the playing field” to favour the outcome we want.

The question we have to ask ourselves, the Internet technical community, is how we want to engage in this. An example of how the technical community has in the past is RFC2804, which documents how the community formally declined to participate in The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act in 2000. This example, Dave said, contradicts what the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (SA 3 WG) have previously stated that they’ll do and accommodate in their process whatever the government wants. But this may be to misread what the 3GPP actually said.

What if the 3GPP wording actually is what allows us to “tilt the playing field” a bit?

I’m unsure of my position on all of this, because I am deeply concerned we’re believers in technological fixes and I have always been skeptical that technology can paper over the underlying problems. The idea that a computer preserves your privacy is compelling, when you think about software like PGP. But if you consider how easily your keys can be broken by bugs, or by having the password obtained from you by the force of law (or just plain force), maybe it’s not true?

However, judging by the chatter inside working groups and on email lists, the idea of the tussle is now strong in people’s minds – it has been referred to several times in the context of the fundamental differences which emerge between competing points of view inside a standardization process. This begs the question of the community involved in the APNIC policy process: are we ready to acknowledge the tussle in our own back yard?

The obvious example is the tension surrounding the issue of privacy of public registry data, and the requirement for law enforcement agencies to have access to timely and accurate data about address dispositions. But even inside address policy, we have possibilities for a conversation about who benefits from the decisions in the final /8 policy, or in access to IPv6 resources by non-traditional ISPs (community network organizations for instance) where the disruption of the underlying process exposes the tensions between old and new models of address use.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.