The sacred mountain Shiliin Bogd in Dariganga is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Mongolia.

Legend has it that when Mongolia was under the Qing rule, ‘good men’ used to gather at the mountain to take an oath for the ‘sacred deed’ of robbing from wealthy Qing occupants and giving to poor Mongolians (similar to Robin Hood). Today, locals believe that the inner spirit of any man who climbs to the top of Shiliin Bogd is revived.

Unfortunately, when they say ‘man’ here, they mean that quite literally. Females are forbidden to climb to the top of this mountain and are only allowed to walk around the base of it. Why you ask? Well, it is also popular belief that the deity of the mountain is not fond of female energy due to the fact it was once a meeting place for ‘good men’.

Considering my experience of being a woman working in the ICT sector in Mongolia, I believe Shiliin Bogd is the perfect metaphor for explaining the diversity struggles in the Mongolian ICT industry.

View of the mountain – Woman in Mongolian ICT

In gender research, it is believed that whenever the gender distribution in any particular area exceeds a 60:40 ratio, it means that one gender is not enjoying the same opportunities as the other [PDF 1.7 MB].

According to labour market statistics by the National Statistics Office of Mongolia, in 2016 there were 19,400 people working in the ICT sector, of which 8,190 (42%) were female. Considering this ratio, women working in the Mongolian ICT sector do not seem to be under a serious problem of discrimination; they even have better representation than some sectors such as electricity, mining, transportation or construction. However, before jumping to this conclusion, it’s worth considering what does the ‘ICT sector’ actually means in this context?

The above statistics were based on something called the ‘Classification of economic activities’ — 8,190 is the total number of women working in organizations that are engaged in ICT-related economic activities, including publishing, recording, broadcasting, programming, telecommunications, and information services. In other words, it does not necessarily mean all those women are working in technical or ICT-related roles. Therefore, the above statistics are not suitable to draw a solid conclusion about the number of women working in the Mongolian ICT industry.

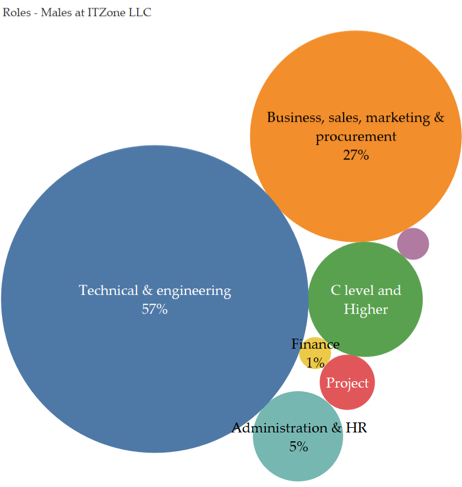

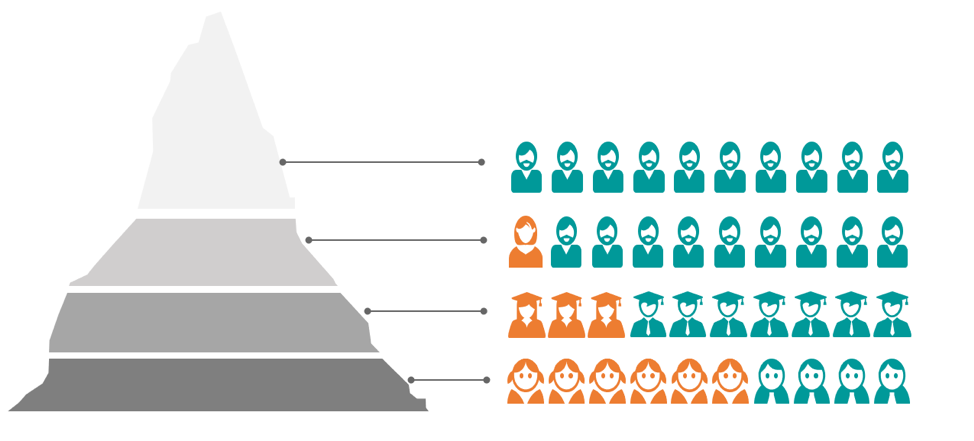

Unfortunately, there are no existing statistics on exactly how many women are working in ICT or technical-related roles in Mongolia. If we draw from the previous statistics, we could conclude though, that most of them work in non-technical roles such as administration or customer relations. As an example, in the leading IT company in Mongolia with over 250 employees, women comprise 33% of its workforce but only 10% of females work in technical positions, while 57% of males work in technical positions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gender distribution of roles at Mongolian ICT organization, ITZone LLC (males left, females right).

Planning a visit to the mountain: Supply problem

Why are there so few women in tech jobs even though there are many women working in the ICT sector itself? No doubt there are multiple reasons, however, many would be related to not enough girls choosing to pursue ICT or tech careers in Mongolia.

Looking closely at this ‘supply’ issue, I believe Mongolian high school girls have every chance to focus on ICT if they want to — the prerequisite for any high school graduate who wants to study ICT is a sufficient maths score in the university entrance examination. In addition, Mongolian parents and teachers should encourage girls as much as boys to take maths courses from an early age. I followed the same path as my male classmates and successfully competed with them in all levels of Maths Olympiads as ‘equals’ during my school years.

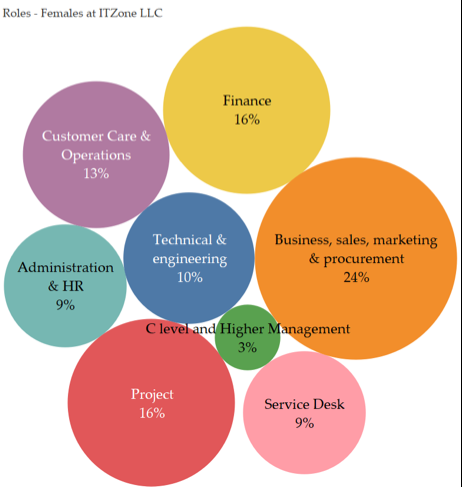

Figure 2: Although more females complete their entrance examination for university, few will graduate with a degree in a technical field and less will pursue a technical career.

In 2017, approximately 55% of all entrance exam takers were female, of which only 1.3% elected to pursue an ICT-related field of study. In contrast, 4.5% of men chose to study in this field.

If we look closer at these statistics (from the Mongolian Ministry of Education during the academic year of 2016-2017), there were 157,138 students (~58.2% of them were female) studying at tertiary institutions, of which 4,171 students (28.5% of them were female) were majoring in ICT.

Although the majority of students entering and studying at Mongolian tertiary institutions are female, very few of them choose to pursue ICT.

Some people claim that the ICT sector of Mongolia does not have a gender problem and that Mongolian girls have every opportunity to pursue a career in ICT but they chose not to; it’s their personal choice and they enjoy the right to choose. I do not agree with this claim and am convinced that those ‘personal choices’ are not always as personal as they appear.

Returning to my reference about the sacred mountain — when making a choice about holiday destinations, many Mongolian women rule out Shiliin Bogd either because they know that even if they visit the mountain they are not allowed to climb to the top, or they think they will be surrounded by people they do not relate with and who do not appreciate them for being there. Similarly, when it’s time to choose their future career, most girls end up not choosing ICT or tech-related careers because of similar reasons. Therefore, girls’ personal choices are heavily influenced by gender stereotypes, stereotype threats, and existing social norms, which all discourage women from choosing ICT.

Visiting the mountain: Choosing to major in ICT

When talking to female colleagues with tech or engineering degrees, I was surprised to discover that almost all of our career decisions were influenced by our parents’ advice. Like many other group-oriented Asian cultures, Mongolians place great emphasis on family and most decisions are made collectively.

I chose to major in Computer Science in India because of my father’s advice. He believes technology is the future, and I believe him. Similarly, some parents understand that technology is everywhere, and a background in tech is essential for every profession in the world. For that, we are forever thankful.

One of my colleagues shared a memory of her first day at university. She remembered how one of her professors had said to the class:

“All of you should study hard to become ICT engineers. However, girls should study even harder because most employers tend to choose male engineers over female ones given the same level of academic qualifications. Because guys can lift heavy cables, racks at ease and can be available at any time.”

In most cases that does not stop women — Mongolian women, as a whole, do as well as or even better than boys as measured by their GPAs at ICT universities.

At the base of the mountain: Graduating with an ICT degree

The harsh truth is that women who graduate with degrees in engineering, computer science and ICT are less likely to be employed in tech jobs than men. To some extent, companies recruit male engineers, programmers or system admins because of the suitability of job conditions (this is not only specific to the ICT industry).

However, with the rise of modern technologies such as IoT, virtualization and cloud, which ease the physical aspect of tech jobs, Mongolian companies have begun to prefer hiring female applicants over male ones. However, the ‘supply problem’ still lingers. For example, when our company recently posted an ad for a junior system administrator position, only one out of ten interested applicants were female.

I believe another factor contributing to this situation is the fact that Mongolian women internalize existing stereotypes about ICT being a male domain and back off from pursuing tech careers. Instead, those women with engineering or science degrees settle for non-tech careers in ICT or closely related fields such as customer care representatives, IT service delivery managers or call centre operators. And that is why the Mongolian ICT sector ends up with an employment gender ratio of 40:60 with only around 10% of women working in tech jobs.

Like female visitors to Shiliin Bogd Mountain, who climb to a smaller hill nearby to experience the view, Mongolian women with ICT degrees settle for non-tech careers in closely related fields.

Ascending the mountain: Women working in the ICT workplace

As opposed to some stereotypes of the workforce, I’ve found that the Mongolian ICT crowd (or at least people in our company) are rather supportive and polite. This could be explained by the culture in Mongolia: men tend to prove their masculinity by providing help to women, seniors and children. Opening doors for women, carrying their heavy bags, or walking them home is an unwritten code of ethics for Mongolian men. Consequently, when facing a question of “Is it hard to be a female system administrator in Mongolia?”, one of my colleagues answered that “Not at all. I’ve never even had to carry heavy cables. Guys in my department are always happy to do those jobs for me because I am a girl.”

Therefore, I genuinely believe that once a woman is already on the ICT ‘mountain’, people around them tend to be supportive and encourage them to stay on the ‘mountain’, if not to climb to the top.

Then why do we still not see many women on top of Mongolian ICT?

I believe it is something to do with existing gender roles in Mongolian society. In Mongolian art and culture, an ideal woman has always been described as ‘a good mother to her children, a perfect wife to her husband and a caring daughter to her parents’. They are expected to dedicate most of their time to these unpaid tasks.

World Bank data shows that women in Mongolia spend around twice the amount of time as men on household and care work, which does not decline even when they are engaged in paid work.

At the same time, in order to succeed in the field of ICT and ever-changing technology, you have to dedicate a massive amount of time to your job; the amount of time which is a luxury women cannot afford.

To make matters worse, the Mongolian government has an agenda to increase the population of Mongolia (we are just over three million in total) and have developed population policies to emphasize motherhood, offering large cash-for-care benefits to mothers. Fun fact: the Mongolian government presents medals to women for giving birth to more than four children.

Figure 3: Mongolian Former President awarding a ‘Second Order of Glorious Motherhood’ to a woman who has four children (Source: Ikon).

The summit

As an economist, I firmly believe that if we could use the entire workforce pool and their talents, our overall performance would improve, which would inevitably lead to faster development.

However, in Mongolia, the ICT sector is like a sacred mountain and overpopulated by men. We need to change this by engaging and encouraging young girls to choose ICT as an interest, and eventually, as a career.

At the same time, we need to challenge the existing social norms and stereotypes about ICT being a male domain and encourage and ensure women to climb the ICT mountain.

Zolzaya Shagdar is the Chief Operations Manager at Mogul Service and Support LLC — a professional IT service company in Mongolia. In addition to her primary job functions, she is passionate about the topic of gender equality, specifically in the ICT sector.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.