‘Light-bulb’ experiences. That moment when a great idea becomes clear in your mind. We all have them and we all tend to remember them fondly, particularly when they can be attributed to helping establish the Internet across an entire economy.

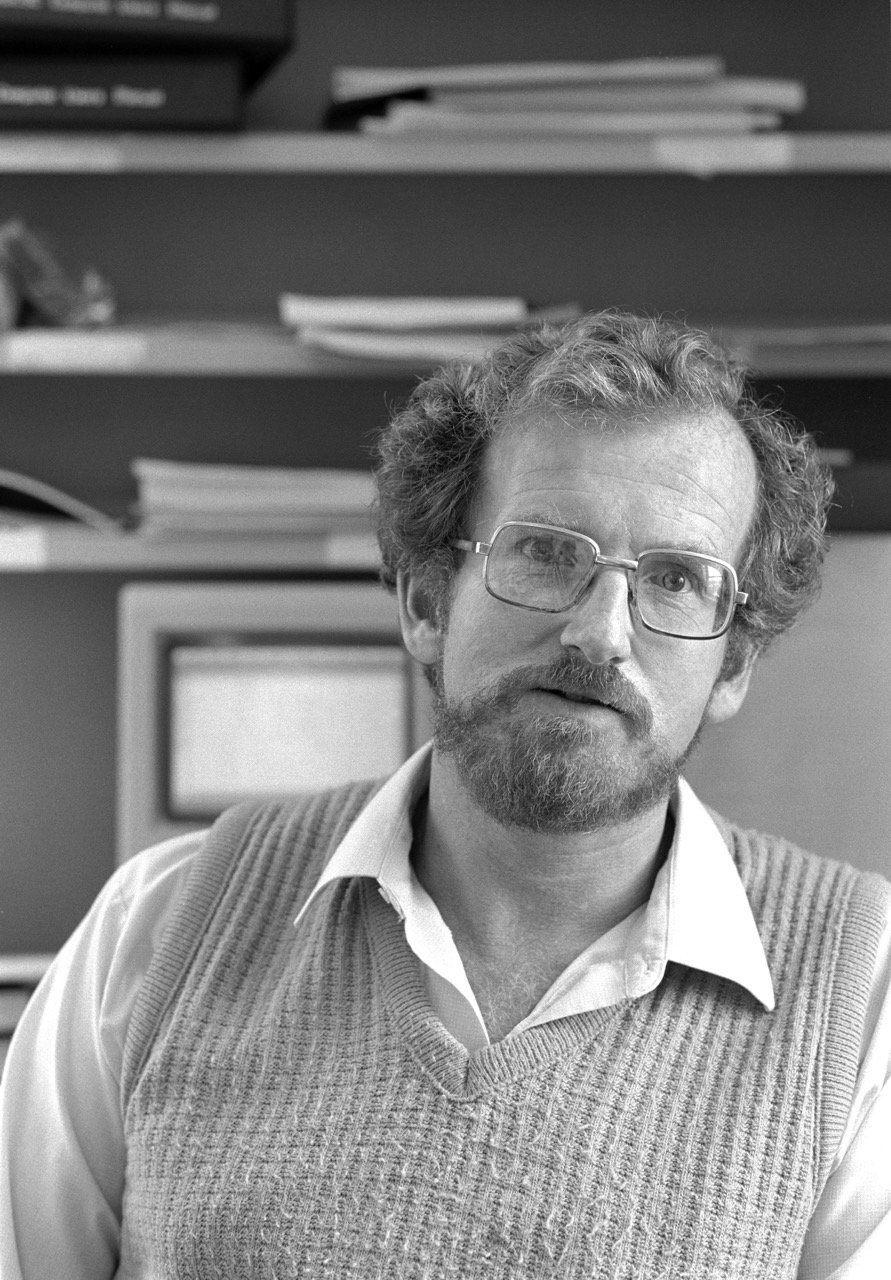

That was the case for John Hine, a professor of computer science at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, when he was invited to the USA in 1982 on a 6-month secondment at the University of Connecticut. It was where he had his first experience with national research networks.

“The first day I was there, I sent an email via the ARPA network to a colleague with whom I had previously worked with in the UK but who was now working at the University of Illinois,” remembers John.

John says the conversation wasn’t all that memorable—“How have things been? What research are you working on?”—but what he remembers vividly was being amazed about receiving an answer to his questions almost instantly.

“Having moved from the UK to New Zealand in 1977, I quickly realized how much I had taken for granted the close proximity of the continental community I was a part of in Europe, and the ease with which we could travel and communicate. In New Zealand you had to make expensive phone calls and write letters, the latter to which you would have to wait anywhere from one to four weeks for a response.

“It was at that time, having this instantaneous conversation with my colleague, I realized what this could do for New Zealanders. For me that was a light-bulb moment, which spurred me to bring this technology to New Zealand.”

Over the next four years John juggled establishing a computer science program in Victoria University’s Faculty of Science, as well as his mission to bring a national research network and early version of the Internet to New Zealand.

Universities take first steps to connect to the world

Universities have played a pivotal role in introducing and establishing the Internet in many countries, including New Zealand.

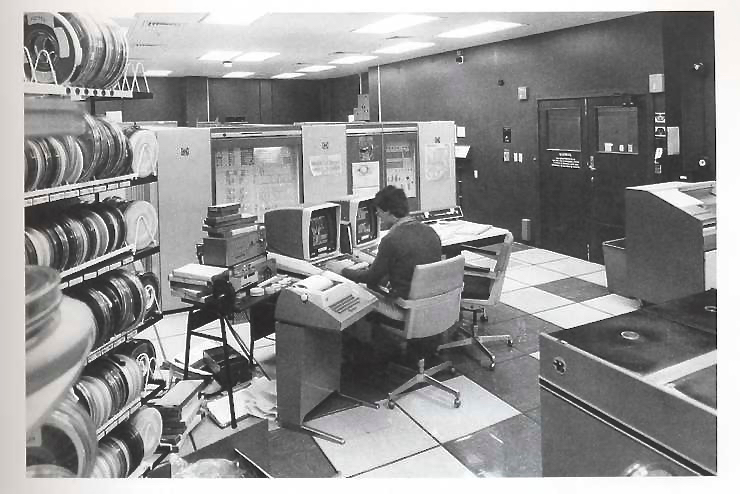

By 1986, New Zealand had “an interconnection of networks” between universities, some government departments and a few commercial organizations.

In addition, at Victoria University, John had successfully helped develop email connections via Unix’s UUCP (Unix-to-Unix copy protocol) to the University of Melbourne, Australia, and the University of Calgary, Canada.

Later that year, New Zealand’s universities started using the Coloured Book Protocols, which allowed access to JANET, a British academic-centred network that linked to more than 1,000 hosts in the UK.

Then, in 1989, John Houlker at Waikato University, with help from John Hine, brokered a deal with NASA to install a 9.6 kB fixed line from Hawaii via the ANZCAN undersea cable; giving New Zealand, and its universities, the first direct connection to the US Internet backbone out of all countries in the Pacific region.

“It was all fairly slow going in the first few years, learning how to set these networks up and getting them to talk to each other, particularly given everyone was using various systems; from IBM to Unix…it wasn’t untypical of the world.

“The hardest part was convincing people that instead of spending two dollars to send a letter and getting a response two to four weeks later, you could spend twenty cents – which seems expensive nowadays – and send an email and get a response in the morning.”

The hard sell: convincing people to use new technology

John often references in his lectures other instances in history where similar aversions to new ways to communicate proved to be difficult to overcome.

“When Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone the obvious people to talk to about selling his concept were Western Union, who had telegraph lines strewn across the country. The CEO at the time said to Bell, ‘Why would people want to talk to each other?’. You look at that now and you wonder what that CEO would think of today’s world with everyone carrying a phone in their pocket.”

Like the telephone, John points out that email – and eventually the Internet – only became popular once more people had access to it.

“Like all networks, if the people you want to contact aren’t a part of the network, it is no good to you. That’s why it wasn’t until we had connected local networks to larger networks in the US and Europe that it became popular among researchers other than physicists and mathematicians, who were the earliest adopters.”

Developing an Advanced Research and Education Network

Through the ’90s, more and more researchers in New Zealand started to use email and the budding Internet, placing pressure on the network which they all helped to build and maintain.

On the basis of the Government’s mantra at the time, universities started to develop their own private networks to gain a competitive edge. What annoyed many people in the networking community was the lack of strategic planning and consideration of the benefits of the previous shared networks, a symptom of the Government and Telecommunication sectors’ own lack of strategic direction.

“A group of us got fed up with everyone’s lack of direction,” remembers John, who worked with the group to develop a report in 2001, arguing the case for an education and research network.

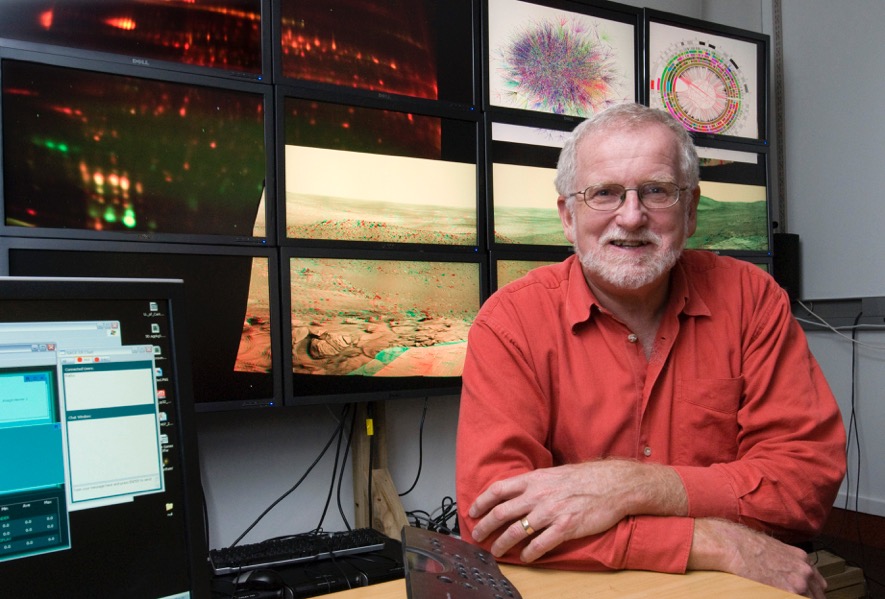

That report eventually led to the establishment of the Kiwi Advanced Research and Education Network (KAREN) – a high-capacity, high-speed national research and education network connecting New Zealand’s tertiary institutions, research organizations, libraries, schools and museums, and the rest of the world.

Note: The name KAREN has disappeared. The network is now referred to as REANNZ (Research and Education Advanced Network New Zealand Ltd), after the crown-owned, not-for-profit company that owns and operates the network.

“It’s vital that governments invest in these national research and education networks, particularly given the contribution R&D and the Internet make to society and the economy,” says John.

“In terms of the research community, you have got to have the infrastructure in place that can download and upload terabytes of data to be able to compete with other laboratories who are clambering to be a part of billion-dollar, large-scale collaborative projects of national and international significance, like the Human Genome Project, Square Kilometre Array telescope and the Large Hadron Collider.

“New Zealand has three Nobel Prize winners, none of which did their work in NZ. Granted the facilities weren’t present at the time. But given the way the Internet can allow many researchers to conduct their research anywhere with a decent Internet connection, it would be nice to not have every good researcher and student leave because we don’t have basic research network infrastructure in place.”

Although the network isn’t perfect, with some researchers struggling to move very large files off campus because of firewalls, John believes it is continually evolving and providing flow on effects for public networks.

“Over the years any number of projects essential to the Internet, and businesses, have started in universities around the world, primarily because of their willingness to share their creations to allow others to use and improve them,” says John.

John cites this ‘open’ spirit as playing a large part in the Internet’s success over rival technologies and in many ways has provided an environment for many others to have light-bulb moments like John.

Image credits: Victoria University

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.